Originally published in The Clarinet 50/1 (December 2022).

Printed copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

Reprints from Early Years of The Clarinet

Over the next four issues, we’ll take a look back at notable articles from earlier issues of The Clarinet, along with photos from The Clarinet archives and commentary from today’s clarinetists. This edition includes a humorous (and still very relevant) article on reeds by Leon Russianoff, and a collection of excerpts from bass clarinet articles by Edward Palanker, Josef Horák, and Harry Sparnaay.

THE REED IS DEAD: LONG LIVE THE REED

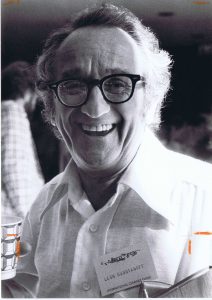

The first of many astute and light-hearted contributions to The Clarinet by Leon Russianoff (1916-1990), this article originally appeared in the second issue, volume 1 no. 2 (February 1974). Russianoff was a student of Daniel Bonade and Simeon Bellison, and himself taught a generation of clarinetists in his time at the Manhattan School of Music and The Juilliard School.

by Leon Russianoff

Leon Russianoff

Photo by Jack Snavely

Before solemnly interring your fantastic reed, the one that only last night expired; before heaping blame upon the weather, the aridity, humidity, altitude, and the nasty effects of the Gulf Stream on your favorite piece of fine French cane, why don’t we pause a moment, “cool it,” and try to see what went wrong.

The clarinet reed has got to be the total scapegoat of all time. We accuse it of every imaginable sin. At the worst it doesn’t play at all. It’s not centered, doesn’t tongue, spreads, squeaks, and closes up; not to mention its occasional whistle. It’s either too dry or too wet, either too old or “not broken in yet.” It can omit rests, ignore time and key signatures, and spoil your performance in a myriad of ways. You name the blemish; it is always the fault of the reed.

If I may be anecdotal and nonpedantic, I should like to describe a typical scene in my New York Studio, whence emanates the so-called “New York Sound.”

ENTER, a new graduate student!

Neatly dressed, attractive, extremely well mannered, I already feel slightly intimidated. Expectantly I say to him,

“Hi, please get your axe out (New Yorkese for “instrument”) and “warm up.” Meanwhile, I am forming some off-hand impressions of this young man. I check out his hair length and general hirsuteness. That tells me a great deal about his musical qualifications. Dialogue ensues.

Me: “Let’s play something; anything that will give me some feeling for your style and general level of playing.”

Now the drama starts to unfold. This nice youngster starts to unload. First, he places his reed-transporter on my desk. I’ve been observing this scene so long now that I usually can guess this diligent fellow’s latest teacher by his reed holder: A Reed-Guard, with red numbers 1-4 on the reed itself is either teacher A, B, or C. (The fancier version has blue and white Dymo tape numbers on the Reed-Guard.) If it is a high class tan leather holder with glass, it is teacher “D”. Teacher “E” usually uses black pigskin, while beveled glass and a rubber band arrangement usually indicates “F”. One dirty, chipped old reed and a metronome is “G”. That’s me.

Every once in a while, a champ appears. This is the guy who carries his reed in a plastic medicine bottle full of some suspicious looking liquid, which, sadly enough, turns out to be plain rancid water. He de-submerges the reed, shoves it into his mouth to make sure it is really moist, and slaps it on the clarinet. I like it okay. He just cannot stand it and lugubriously announces that the reed doesn’t play because of the high New York humidity, and, alas, that wonderful reed he was playing before suddenly passed away last night at 1:23 a.m. At this point I demand that he produce the corpse. He reluctantly complies and, lo and behold, the resurrection. The reed plays like a dream! Yes, it happens all the time! The statistics on sudden mortality for clarinet reeds are staggering.

I am zoomed in on this issue because I passionately feel that this attitude about reeds engenders a blocking mental set, tension, and avoidance of the necessity of facing up to the realistic demands of clarinetistic and artistic growth. I believe in the essentially inanimate character of reeds—the cause of difficulties in execution are many and variable, and, above all, elusive and subtle.

To start with, on a positive note, I should like to focus on some of the daily variables that might possibly, and I believe actually do, account for the overnight demise of our favorite reed.

VARIABLES TO BE CHECKED DAILY BEFORE BURYING THE CORPSE

Variable 1: The Position of the Reed on the Mouthpiece.

Accept no rule of positioning other than that of daily trial through experiment. Trial and error must be the rule, not Tradition, Authority, or Country of Origin. “Does it work?” is the vital question.

Do not put the ligature on until you have searched diligently for the best playing position of the reed on the mouthpiece. Hold the thumb on the reed as a ligature, test by blowing low CDEFG; then with the register key, the third octave GABC. Set reed in standard position. Blow and listen. Shift reed slightly to the left. Blow. Not good? Back to standard position.

Blow. A little better. Not sure? Try again. Now try moving a little to the right. Much better? The same? A little better? Great? A little too soft. Move the reed higher on the mouthpiece. Now slip the ligature on. Test. It must play as well as it did with your thumb holding it.

Variable 2: Position of the Ligature on the Reed and Mouthpiece.

Ignore all “rules” you’ve ever learned. Start with your standard position. Check all others, especially with the ligature higher up on the reed. Try everything. You may be in for a pleasant surprise.

Variable 3: Tightness of Ligature.

Don’t take anything for granted, most students over-tighten the screws. Don’t be a compulsive screw tightener.

Variable 4: Position of Mouthpiece in the Barrel Vis-a-vis your Mouth.

Try standard normal position first. Shift mouthpiece very slightly right, left, back to normal, and check once again for the best sounding position.

SOME VARIABLES THAT CAN BE MADE NONVARIABLE

Variable 1: Position of Barrel.

Find a permanent, best sounding line-up of the barrel joint in relation to the top joint by rotating the barrel about 20° and testing each time. Mark the line-up of the two or three best positions by corresponding lined-up dots on barrel and upper joint.

Variable 2: Ditto as above with bell joint.

Now you can actually set the clarinet each day so the entire body is always lined up in its optimum position for the best sound and pitch.

Variable 3: Pad Leakage.

BEWARE

1 Overtightening of set screw on throat A key. Always leave a slight play for the A key. The reed is not to blame if the clarinet leaks or a pad falls off.

2 Rings must be high enough to give pads good covering leverage, yet still be comfortable.

3 Don’t over adjust the one-and-one B-flat/E-flat at the expense of the entire right hand lower joint. When testing for the B-flat/E-flat, test equally for the third octave F, E, D. They should cover without excessive pressure.

4 Check the following frequently guilty pads: throat G-sharp, A, the C-sharp and G-sharp key, and both E-flat/B-flat keys.

5 Check water condensation. Swab clarinet frequently at the start of practicing until, hopefully, the temperature in the bore will more closely match your breath temperature and will therefore reduce water bubble formation—a constant menace.

I stress all of these factors because if the variables are not carefully checked each day, many of them could accidentally be very “wrong,” and the clarinet then would not perform as well as it did last night. When this happens, we inevitably and automatically blame the reed for our problems. A poor combination of variables has caused me, who should know better by now, to crush a reed in a frenzy of hatred.

These then are some caveats and some suggestions. This has turned out to be, I fear, only a little aperitif of clarinet talk. But if you will be patient, I hope I can find some meat and potatoes in my kitchen. I would be flattered at any comments, pro or con, angry or agreeable. I will very much benefit from some hectic feedback from you. I will try to give my thoughts on whatever topics would interest you. I cannot promise any golden nuggets, shortcuts, or great gems, but you may be sure of my affection, frankness, encouragement, and, above all, the expression of my honest feelings.

- S. “Top Secret” Have you ever really tried burning your reed with a quarter as a model? A universally despised technique which, of course, works great. I have now a collection of 72 assorted reed clippers but, alas, no matches!

RUSSIANOFF ARTICLE COMMENTARY

This article is classic Leon and reminiscent of his appearances at the early meetings of the ICA. The well-attended Russianoff Hour was like a riotous stand-up replete with simple but profound wisdom. Leon’s approach was to move from the “thought-full” to the “thought-less”; from the “self-conscious” to the “un-conscious.” I was privileged to study with both sides of Leon—the pre-Penny (his psychologist wife) and the post-Penny. Both incarnations were fabulous, but with the Penny influence, Leon shifted from a rather analytical approach to that of trusting our instincts; to moving from “over-think” and “over-try” to the joy of making music.

– F. Gerard Errante

I studied with Leon a decade before he published this article, beginning in 1962, and then summers for a few years, and finally the 1967-68 school year. Early on I was learning how to make reeds, which Leon was not particularly in support of. But in his big-hearted way, since he knew I was living a very frugal life, he paid me to give him reed-making lessons. Of course he was not interested in making reeds, but it gave me lunch money and more access to him, for which I am grateful to this day.

– Frank Kowalsky

He never discouraged me from playing bass clarinet and E♭ as well, and was positive (not jealous) when I told him I’d like to study bass with Joe Allard or took semi-monthly master classes with Bernard Portnoy through the National Orchestral Association of New York. When I asked him about ligatures in relation to making a reed sound its best, he replied, “Find a ligature and placement on the mouthpiece that sounds as good as your thumb.” When I asked him whose sound I should most closely try to emulate, he said, “Sound like Eddie Palanker.”

– Edward Palanker

Leon’s effervescent voice and irreverent sense of humor just radiate from this article. As a teacher, his goal was always to keep us from looking for excuses as to why “things” weren’t working. Purported “reed trouble,” or the elusive search for the fabled “perfect reed,” should not be an impediment to our practicing and working hard to learn our craft. Instead, he wanted us to do everything we could to become better musicians—damn the reed, full speed ahead! He treated all his students as unique individuals and did not try to fit them into a particular mold; if they wanted to soak their reads in seltzer, or bourbon, it was all fine with him. To this day, I think of Leon and still move the reed slightly to see (hear) if it is a right-handed reed or a left handed reed; of course, rarely is it centered. And if a bourbon soak leads to a little nightcap for me, well, so much the better!

– Jerome Bunke

I only had four lessons, but would always play for him when the orchestra was on tour. He was a natural psychiatrist and born cheerleader. He gave all of us confidence!

– Michele Zukovsky

Comments are closed.