Originally published in The Clarinet 50/3 (June 2023).

Printed copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

The ICA at 50: The First Two Decades, 1973–1992

This article is the first of a four-part series documenting the history of the International Clarinet Association, in celebration of its 50th anniversary in 2023. It builds on Alan Stanek’s extensive history written for the 40th anniversary in 2013, which may be read on the ICA website (clarinet.org/history). The author is grateful for the assistance of Stanek, Charles West, James Schoepflin, and many others in the production of this series. Readers are also referred to The Clarinet 40 no. 3 (June 2013), which contains numerous articles and remembrances commemorating the ICA’s 40th anniversary.

by Jane Ellsworth

Beginnings

The history of the present International Clarinet Association can be traced back to the National Clarinet Clinic, held at the University of Denver beginning in 1964. This gathering was the brainchild of Ralph Strouf, at that time professor of clarinet at the host institution. Occurring annually, the clinic had many of the same elements as today’s ClarinetFest®: concerts by well-known artists, master classes, a clarinet choir, and exhibits where participants could purchase music and accessories and try instruments by prominent clarinet manufacturers.

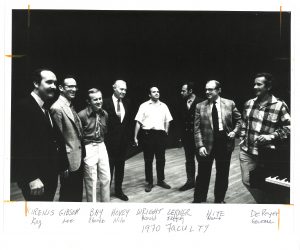

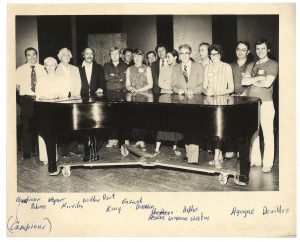

Faculty of the 1970 National Clarinet Clinic in Denver

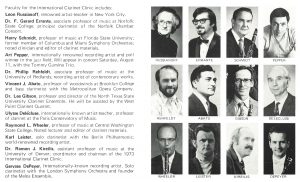

The National Clarinet Clinic continued to thrive and expand under the stewardship of Ramon Kireilis, who had become the clarinet professor at the University of Denver in 1967. By 1973 it was known as the International Clarinet Clinic (hereafter ICC), and boasted a faculty including Leon Russianoff from Juilliard, Vincent Abato of the Metropolitan Opera orchestra, jazz great Art Pepper, and international stars Karl Leister, Ulysse Delécluse, and Gervase de Peyer. The 1973 brochure promised “a series of lectures, recitals and discussions on clarinet performance, pedagogy and manufacture.” In addition, by the time of that year’s clinic, interest in the ICC had grown to the extent that Kireilis proposed the creation of the International Clarinet Society (ICS). The two entities were to be separate from and independent of each other, but the ICS would hold its annual business meeting during the ICC. Kireilis was elected president; the other officers were Leon Russianoff, vice-president, and Robert Schott (Kansas State College), secretary-treasurer.1

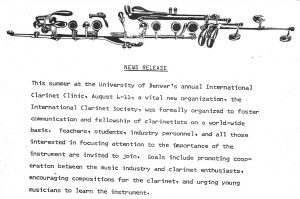

Excerpt from a 1973 news release by Ramon Kireilis about the formation of the ICS

From the outset, a journal was planned as an important component of the ICS, and O. Lee Gibson (North Texas State University) was named the editor of The Clarinet. In the very first issue of the journal, Gibson outlined some of the proposed aims and projects of the new organization:

1 Foster communication and fellowship of clarinetists on a world-wide basis. Teachers, students, industry personnel, and all those interested in focusing attention on the importance of the instrument are invited to join.

2 Encourage, by the various means, including commissions, the composition of works for the clarinet.

3 Provide a library for the instrument having international availability.

4 Furnish a complete and continuous catalog of music for the clarinet. We propose to begin such a catalog with Volume I, No. 2, our next issue. While Opperman, Rendall, Kroll, and others are helpful, all of these taken together supply lists of no more than half of the publications which are currently available.

5 Share knowledge of the instrument in its amazingly varied realizations in different parts of the world. While the arts of musical expression are truly universal, no instrument offers a greater variety of tonal realizations and mechanical systems than does the clarinet. Perhaps the greatest strength of the 1973 International Clarinet Clinic was the presentation of artists of dramatic, quadripolar contrasts in tonal preference, each being a virtuosic exponent. One must cite DePeyer, Delecluse, Salander, and any of the excellent U. S. players as representatives of these polarities. Within the next half-century a clarinet may possibly be developed which will become definitive the world over as did the stringed instruments of Stradivari after 1740!2

Faculty of the 1973 International Clarinet Clinic, from a brochure advertising the event

One senses the great optimism and excitement of the young organization, and many of its aims were to be met in the coming years, even if some of them now seem impossibly ambitious. The catalyst for meeting many of the goals was The Clarinet. Early issues featured articles by various writers on history, composers, repertoire (old and new), pedagogy, and equipment (Lee Gibson’s “Claranalysis” column), as well as reviews (music recordings, books) and news from the clarinet world at large, establishing some of the basic components still found in the journal to this day. Other features in the first couple of years included profiles of prominent clarinetists, stories about the clarinet sections of various orchestras, reports on the annual clinic, recital programs submitted by members, and letters to the editor. A comprehensive catalog of clarinet music was never attained, but repertoire articles (some of which were largely lists of music) served the aim of supplementing the published resources cited by Gibson. The journal was painstakingly typed, laid out, taken for printing, and then packaged and mailed to the membership by H. James Schoepflin and his assistants at Idaho State University, especially Betty Brockett.3

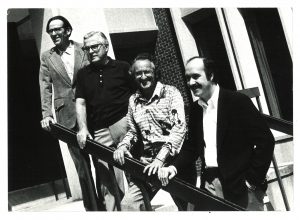

(Left to right) Lee Gibson, Robert Schott, Leon Russianoff, and Ramon Kireilis at an early Denver clinic (c. 1973)

Work on another of the ICS’s initial aims, the establishment of a library, also began early on. At first undertaken by Robert Schott at Kansas State College, the library moved after about a year to the University of Idaho under the supervision of Cecil Gold. Donations of music, books, articles, theses, dissertations, and recordings were solicited through announcements in The Clarinet, and the effort was given a strong impetus when Burnet Tuthill donated his entire personal library to the cause.4 Lists of music housed in the library, and new additions, began appearing on a regular basis in The Clarinet starting with the May 1975 issue; donations from publishing houses and individuals contributed to the steady expansion of the holdings.

Daily schedule from the first day of the 1973 International Clarinet Clinic in Denver

An active relationship with the clarinet industry was also made an explicit aim in early expressions of the ICS’s goals. In his first message as president, Kireilis outlined a number of reasons for membership, including to “encourage manufacturers to listen to our pleas for a more definitive clarinet.”5 Although the perfect clarinet has yet to be designed, there is no doubt that the ICS spurred a fruitful engagement between manufacturers and clarinetists that has led to innovations and improvements, not only in clarinets but also in reeds, ligatures, and other types of merchandise. In turn, industry members have been wonderful partners of the ICS/ICA over the years, through advertising and support of events and competitions.

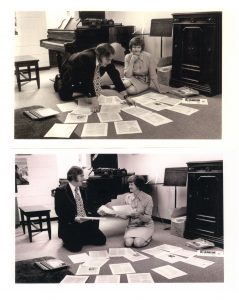

James Schoepflin and Betty Brockett work on the layout of The Clarinet 3 no. 1 (Nov. 1975)

The final issue of The Clarinet’s first volume contained a proposed constitution for the ICS, which was adopted by vote at the 1974 clinic; by the end of the first year, membership numbered nearly 800.6 In addition to the organization’s three main officers, there were regional chairs, national chairs for Canada, Australia, Austria, England, and Mexico, contributing members from the clarinet industry, and a job vacancy service. Standing committees had been formed for the library, publications, reed and mouthpiece research, resonator and mechanism research, sound archives, bylaws, nominations, and finance.7 The Clarinet maintained an editorial and publishing staff, including an advertising manager. With the assistance of member and volunteer attorney Harry “Bud” Rubin, articles of incorporation for the ICS were in place by August 1975, and after some amendments to the bylaws, tax-exempt status was finally achieved in 1978.

(Left to right) Cecil Gold, Beth Ford, Dave Weyrick, and Kim Ayres at the ICS Research Library at the University of Idaho, before Gold moved the library to Akron in 1976

That year was a banner year in many ways. It ushered in the first change of president, from Ramon Kireilis to Lee Gibson. James Gillespie, who had been editor of reviews since the second issue of The Clarinet, became the new journal editor, a position he would fulfill excellently for the next 37 years. It was also in 1978 that the ICC was held outside of Denver—and outside of the United States—for the first time. Because Kireilis was on sabbatical from his position at the University of Denver for most of the 1977–78 academic year, and therefore unable to organize the usual clinic, the University of Toronto was chosen as the location for the ICC, under the direction of Avrahm Galper (then principal clarinetist of the Toronto Symphony). Although the ICC had always hosted a few European clarinetists in addition to the many Americans who regularly performed, the Toronto “Clinic/Congress” featured a wider array of international headliners, including Jack Brymer, Yona Ettlinger, and Karl Leister, as well as leading American players Stanley Drucker, Mitchell Lurie, and David Weber. The renowned physicist and clarinet acoustician Arthur Benade also presented lecture-demonstrations. A star line-up indeed!

Robert (Bob) Luyben and Annette Luyben of

Luyben Music, early sponsors and exhibitors of the ICS and its events

Since 1971, a clarinet competition had been an important component of the ICC. The competition was initially open only to US high school students; by 1975, however, the age limit had been raised to 19, and the scope widened to include competitors from other countries. Between that time and 1992, the age requirement changed a number of times, ranging from an upper limit of 30 (from 1982–84) to 22 (1985–87) and then 23 (1988–92).8 Clearly, it had grown from a High School Competition to a Young Artist Competition, and the name was eventually changed to reflect that fact.

Karl Leister in a workshop session at the 1978 International Clarinet Congress/Clinic in Toronto

During Lee Gibson’s presidency (1978–80), the society continued to grow. At the 1979 annual meeting, secretary Alan Stanek reported that membership stood at 1,179, with 178 of those members residing outside the United States. The ICS Research Library moved from Idaho to the University of Akron, and then to the University of Maryland, where it still resides today; Norman Heim served as library director from 1980 to 2006. Jim Gillespie diversified the writers for The Clarinet, adding some regular columns such as “Denmania” (John Denman), “Care and Repair” (Robert Schmidt), and “Swiss Kaleidoscope” (Brigitte Frick). The ICC returned to Denver for 1979 and 1980, but the idea that it should be held outside the United States every third year had been born.

Leon Russianoff, Michele Zukovsky, and Hans Rudolf Stalder at the 1977 International Clarinet Clinic in Denver

Growing Pains

Jerry Pierce served as ICS president for the period 1980–86. In his regular column in The Clarinet, “Pierce’s Potpourri,” he kept readers informed of developments in the clarinet world, especially of his own discoveries of rare and unknown clarinet repertoire. The push to be a truly international organization continued. Pierce’s presidency included two International Clarinet Congresses (the new name for the ICC) outside the United States: Paris in 1981, and London in 1984. Several new national chairs were named (Argentina, China, and Spain), and by fall 1982 each US state had a chair.

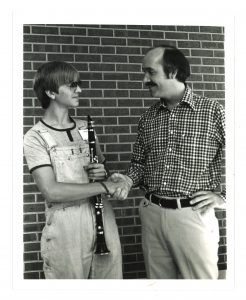

Ramon Kireilis, then president of the ICS, congratulates 16-year-old Bil Jackson, winner of the 1976 International Clarinet Competition. Jackson, then a student at Interlochen Arts Academy, played for the competition Bergson’s Scene and Air, D’Ollone’s Fantasie Orientale, and Weber’s Concerto No. 1.

In the “Pierce’s Potpourri” column of Winter 1982, Pierce noted the creation of a new clarinet organization called ClariNetwork InterNational, Inc. Two primary factors motivated the formation of ClariNetwork: First, there was a perception that the ICS was mostly for clarinetists associated with academia, and less relevant to symphony clarinetists and other performers; and second, clarinetists on the East Coast of the US wanted conferences that were geographically closer than the traditional location in Denver.

At the 1980 Denver International Clarinet Congress (left to right): Carmine Campione, Georgina Dobrée, Robert Vagner, Ramon Kireilis, Mark Walton, Gerard Dort, Thea King, Michel Gizard, John Denman, Suzanne Stephens, Himie Voxman, Guy Deplus, Pamela Weston, René Agogue, and Patrick Dovillez

The question of location for the International Clarinet Congress had already been on the minds of the ICS leadership. The minutes of the 1978 annual meeting as printed in The Clarinet of Fall 1978 noted laconically, “future meetings of the Society were discussed at length.” In the “Announcements” section of the same issue there was a call for location proposals for the 1980 ICC. Among the sites being considered were College Park, Maryland; Dallas, Texas; Akron, Ohio; and Denver, where it was ultimately held. In 1982 Ramon Kireilis suggested a three-year rotation that included one year in Denver, one year somewhere else in the US, and one year outside the US, noting that “this plan has the possibility of appeasing the East Coast (and West Coast) people, maintaining tradition for those who yearn for Denver each summer and establishing the precedent of inviting a foreign country to host the Congress every third year.”9 Indeed, such a cycle started in 1983 (Denver), 1984 (London), and 1985 (Oberlin), but after that Denver disappeared altogether from the rotation.

The Clarinet journal continued to offer the usual range of regular columns, articles, reviews, and reports. Writers kept up with the latest technological developments. For example, in his column “Record Rumbles” of Summer 1983, Jim Sauers announced, “Compact Discs are here.” After explaining to readers what this new medium was, Sauers opined that it was probably no immediate threat to the long-playing record, especially since he was able to locate only one woodwind-related CD in publication at that point!10 Computers aided the ICS in various ways; at the 1984 annual meeting it was noted that the membership list has been “computerized.”11 In 1986 Betty Brockett retired as printer of The Clarinet in Idaho Falls, and for ease of access Jim Gillespie found a printing company in Dallas to take over. This brought some changes in the look of the journal, including a move from the old two-column format to the three-column layout that the journal still maintains.

James Gillespie, Dan Sparks, and Thea King in Paris for the 1981 International Clarinet Congress

By the end of Jerry Pierce’s long presidency, ICS membership stood at 2,100. At the 1985 annual meeting, membership dues had been raised to $20 inside the US and $30 outside. By the beginning of John Mohler’s presidency a year later, however, the ICS had a $3000 shortfall in the budget, so it was decided to raise US dues to $25, and to reinstate a student membership at $20. Increasing the number of members was seen as a necessity, and Vice President Alan Stanek was asked to spearhead a membership campaign.12 Several other important decisions took place during Mohler’s term (1986–88). First, at the 1986 annual meeting it was decided that the annual conference would be renamed the “International Clarinet Society Conference,” signaling the end of the separation between the ICS and the clinic/congress/conference. Second, at the 1987 annual meeting it was reported that a merger between the ICS and its sister organization, ClariNetwork InterNational, had been agreed on in principle; a resolution was drafted allowing for the basic outlines of the merger, and it was adopted by vote, although the merger itself would not be in effect until the following year. Additionally, it was decided that the 1988 conference in Richmond, Virginia, would be a joint conference between the two organizations.13 The new organization’s name would be the International Clarinet Society/ClariNetwork InterNational (ICS/CI). At the annual business meeting in Richmond, the merger was unanimously approved by the membership.

Solutions and Expansion

The director of the successful joint conference of 1988, Charles West, who had been serving as the ICS treasurer, became the next ICS/CI president. He immediately started to address the declining membership problem by inserting several copies of the membership brochure into the November/December 1988 issue of The Clarinet. That effort, along with the merger of the two organizations—which already had a significant overlap of members—successfully raised the total membership by 15%, to around 2,400 by the time of the 1989 annual business meeting.14 Several further significant changes took place in West’s first year. The position of vice-president became president-elect; a computer was purchased for Jim Gillespie, so that contributors to The Clarinet could turn in their articles on a disc, saving much time and money on typesetting; and non-US dues were raised to $40 to cover increasing costs. In relation to the Clarinetfest (West’s suggestion for the new name of the annual conference), it was decided that organizers would benefit from greater planning time, and conference sites would be chosen two years out. On the heels of the 1989 conference in Minneapolis, Minnesota, the 1990 site was announced as Quebec City, Canada, and 1991 was planned for Flagstaff, Arizona.15 Additionally, to simplify the tasks of the Clarinetfest organizer, the responsibility for the Young Artist Competition was given to the president-elect.

Concert programs from the 1983 International Clarinet Congress in Denver

The annual commissioning of compositions had been proceeding for a number of years under the able guidance of Linda Pierce and an international committee of screeners. In 1988 the process was reorganized to occur every other year, “combining and amplifying two years’ budgets with the hope of enticing one of the world’s foremost composers to produce a new work for clarinet.” In addition, it was felt that “a format likely to be useful to the greatest number of clarinetists is preferable to odd combinations of instruments.”16

Concert programs from the 1983 International Clarinet Congress in Denver

The commissions for 1989 and 1990 were already in train, so the change was to take place beginning in 1992. Virgil Thomson was approached first, but passed away before he could fulfill the commission; then Robert Muczynski was asked, but had to withdraw for personal reasons. Ultimately, Leslie Bassett agreed to write a work for clarinet and piano, to be completed by 1993. (The end result was Bassett’s Arias, premiered at the 1993 ClarFest in Ghent.)

Concert programs from the 1983 International Clarinet Congress in Denver

By the end of West’s presidency, membership had risen an additional 18%, standing at 2,836. The budget had steadied. As the journal of ICS/CI, The Clarinet continued to flourish. Over the previous few years, Jim Gillespie had recruited a number of new regular columnists, including Rosario Mazzeo (“Mazzeo Musings”), Tsuneya Hirai (“News from Japan”), Bruce Creditor (“Quintessence,” a column about woodwind quintets), Howard Klug (“Clarinet Pedagogy”), and others.

Concert programs from the 1983 International Clarinet Congress in Denver

The long-standing columns “Claranalysis” and “Pierce’s Potpourri” continued, along with the standard articles, player and section profiles, interviews, reviews, and general news of the profession.

James Pyne conducting The Ohio State Clarinet Choir at the 1988 joint conference of the International Clarinet Society/ClariNetwork InterNational in Richmond, Virginia

The next president of the ICS was Fred Ormand (1990–92). Since one can never take membership growth for granted, Ormand continued to focus on that as one of his concerns, along with increasing attendance at the annual conference and “developing stronger and more open lines of communication with the music industry, especially in relation to the convention.”17 The Clarinetfests that took place during Ormand’s presidency were in Flagstaff, Arizona (1991), and Cincinnati, Ohio (1992). The Flagstaff Clarinetfest was the first in which ICS members could submit proposals to perform on the morning “potpourri” concerts.18 At the 1990 business meeting a name change for the organization was discussed, since some members had expressed the feeling that the compound title, International Clarinet Society/ClariNetwork InterNational, was too clumsy. It was decided that a list of potential names would be drawn up, published in a future issue of The Clarinet, and put to a vote of the membership. A ballot for ranking five choices was issued in the May-June 1991 issue, and at the 1991 annual business meeting it was announced that the top two choices were Clarinet International or International Clarinet Association. In the end the membership voted for the latter, by a margin of 246 to 137.19 At the close of Ormand’s term there had been a small net gain in members, now numbering 2,879.

Thus, after two decades in existence, thanks to the dedication and hard work of many individuals, the fledgling ICS had grown into the ICA, a flourishing professional organization with nearly 3,000 members. The annual Clarinetfest provided the opportunity that the founders envisioned: in Lee Gibson’s words, “fellowship of clarinetists on a world-wide basis.” The Clarinet journal fostered that fellowship year-round, as well as providing a forum for many of the other goals of the organization. In short, the ICA was well poised for an exciting future of ongoing growth, improvement, and diversification.

Endnotes

1 For more detail on the early years, see Ramon J. Kireilis, “Recollections from the Early Years: The Founding of the International Clarinet Society,” The Clarinet 40, no. 3, 57–59.

2 Lee Gibson, “The International Clarinet Society,” The Clarinet 1, no. 1 (October 1973), 1.

3 James Schoepflin, “Musings on Inventing The Clarinet Magazine,” The Clarinet 40, no. 3 (June 2013), 60–61.

4 Ramon J. Kireilis, “The International Clarinet Society—After One Year,” The Clarinet 2, no. 1 (December 1974), 4.

5 Ramon J. Kireilis, The Clarinet 1, no. 1 (October 1973), 2.

6 Ramon J. Kireilis, “The International Clarinet Society—After One Year,” 3.

7 As announced in The Clarinet 2, no. 2 (February 1975), 4.

8 A list of competition winners from 1973 to 2020 can be found at https://clarinet.org/competitions/competition-winners.

9 Ramon Kireilis, “The 1982 International Clarinet Congress and Competition,” The Clarinet 9, no. 2 (Winter 1982), 12.

10 Jim Sauers, “Record Rumbles,” The Clarinet 10, no. 4 (Summer 1983), 34.

11 “Annual Meeting of the ICS,” The Clarinet 12, no. 1 (Fall 1984), 5.

12 David Pino, “Minutes of the General Business Meeting,” The Clarinet 14, no. 1 (Fall 1986), 38–39.

13 David Pino, “Minutes of the International Clarinet Society General Business Meeting,” The Clarinet 15, no. 1 (November-December 1987), 41–42.

14 “Minutes of the General Business Meeting,” The Clarinet 17, no. 1 (November-December 1989), 68.

15 Charles West, “Memo to the Membership,” The Clarinet 17, no. 1 (November-December 1989), 74.

16 Charles West, “Memo to the Membership,” The Clarinet 16, no. 3 (May-June 1989), 54.

17 Fred Ormand, “A Note to the Membership,” The Clarinet 18, no. 1 (November-December 1990), 56.

18 The tradition of concerts with multiple performers, featuring clarinetists other than the well-known “headliners” of the conference, had been in place for several years; at the Oberlin conference they were called “ICS Concerts,” while at the Seattle event they were called “Noon Showcase.” The term “Potpourri Concert” started at the University of Illinois conference in 1987, and this term has been in use ever since.

19 Fred Ormand, “A Note to the Membership,” The Clarinet 19, no. 3 (May-December 1992), 64.

Jane Ellsworth is both a musicologist and a professional clarinetist. She is program director and professor of music history and clarinet at Eastern Washington University. Her books include A Dictionary for the Modern Clarinetist (Rowman & Littlefield, 2015) and The Clarinet (University of Rochester Press, 2021), as well as a forthcoming monograph on the clarinet in 18th- and 19th-century America. Ellsworth is also bass clarinetist with the Spokane Symphony.

Comments are closed.