Originally published in The Clarinet 47/2 (March 2020). Printed copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

Master Class: Fantasiestücke (Fantasy Pieces), Op. 43 by Niels Gade

by Wesley Ferreira

Niels Wilhelm Gade lived from 1817 to 1890, spanning an era of heightened romanticism in the arts. Although his music is often considered highly influenced by them, he never quite achieved the fame of his close friends and contemporaries Felix Mendelssohn and Robert Schumann. Nevertheless, he was widely regarded as the most important Danish musical figure of his time, teaching and influencing several young Scandinavian composers including Edvard Grieg, Carl Nielsen and Otto Mallingand. His extensive musical output includes eight symphonies, cantatas, numerous overtures, several chamber works, lieder and chants, and works for organ and piano.

Born in Copenhagen, Gade emerged as a talented violinist, earning a position with the Royal Danish Orchestra. When his first symphony was rejected for performance in Copenhagen, he sent it to Mendelssohn who enthusiastically performed the premiere in Leipzig. Soon thereafter, Mendelssohn engaged the previously unknown Gade as assistant conductor of the Gewandhaus Orchestra and as a teacher at the Leipzig Conservatory under him. While in Leipzig Gade was immersed in contemporary artistic life. He was invited into Schumann’s inner circle, the musical society Davidsbündler (a group that was created to defend the cause of contemporary music against detractors). Following outbreak of war between Prussia and Denmark in 1848, Gade returned to Copenhagen where until his death he continued composing, helping to establish a permanent symphony orchestra and chorus which he raised to an international standard, and serving as director of the newly established Royal Danish Academy of Music.

Fantasiestücke, Op. 43, was composed in 1864 and was first published in 1865 by the Kistner publishing house in Leipzig. The work’s title often appears under its English (Fantasy Pieces) and Danish (Fantasiestykker) translations. The concept of “fantasy pieces” is credited to Robert Schumann, who pioneered the category beginning in the late 1830s as a set of shorter pieces, each colorful and with a different mood or character and meant to be performed together. In Op. 43, three of the four pieces are written in the mid-romantic style and exemplify distinguishing features of Romantic music: originality of theme, a push towards dramatic expressiveness, and an expanded harmonic vocabulary. The third piece, Ballade, is the only movement with its own title and is perhaps the most personal of all the pieces in Op. 43. Composed as a musical narrative based on the rich history and style of Scandinavian folk tales, here too Gade operates under Romantic-era conventions of expressing his nation’s distinctiveness through music. During his lifetime, Fantasiestücke was one of Gade’s most popular works. Although originally composed for clarinet it was arranged for several other instruments.

Movement 1

With indications of Larghetto con moto in the autographed manuscript copy and Andantino con moto in the first published edition, the performers may use discretion with respect to tempo. The con moto marking is the most informative and should guide the pianist to move the line forward on repeated eighth-note figures. The first movement is as close to a lieder or art song as we find in the clarinet repertoire. This gives the performers great liberty to exaggerate the music according to what is in the score, and the freedom to tastefully play with time and pulse. When possible, bring out the vocal quality of the clarinet lines and figures. For example, in measures 9 and 10 we might imagine articulated speech in the dolce figure. In general, perform the dynamic indications as expressed by the composer and when none are present, a good general rule is to shape figures following their contour. Increase energy and volume when ascending, and decrease energy when descending. Keep articulation light. Both clarinetist and pianist should aim to match note lengths. Bring out the accents appearing as >, emphasizing these notes more with air weight than initial attack with tongue. Most of the phrases of this movement should be performed with a sense of long line, however in phrases where these accents are present there is the opportunity for contrasting this.

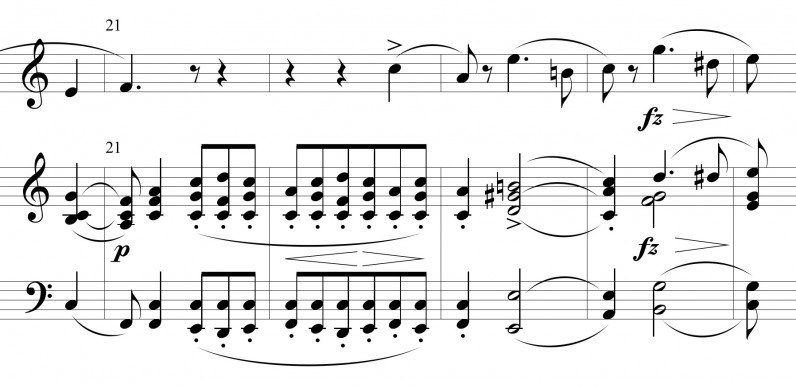

Example 1

The relationship between the clarinet and piano parts must be considered. At times both instruments communicate a shared idea, but there are instances where the two are at odds (Example 1).

After a cadence point on the downbeat of measure 21, the piano, heretofore serving in a purely accompaniment role, for the first time initiates a melodic idea all its own. The harmony outlines a movement towards the downbeat of measure 23, but before this occurs, the clarinet, not to be outdone, interjects on the third beat of measure 22 as if to reclaim our attention. This is a moment that appears again later in the movement. It can serve to heighten the descriptive aspect of the music.

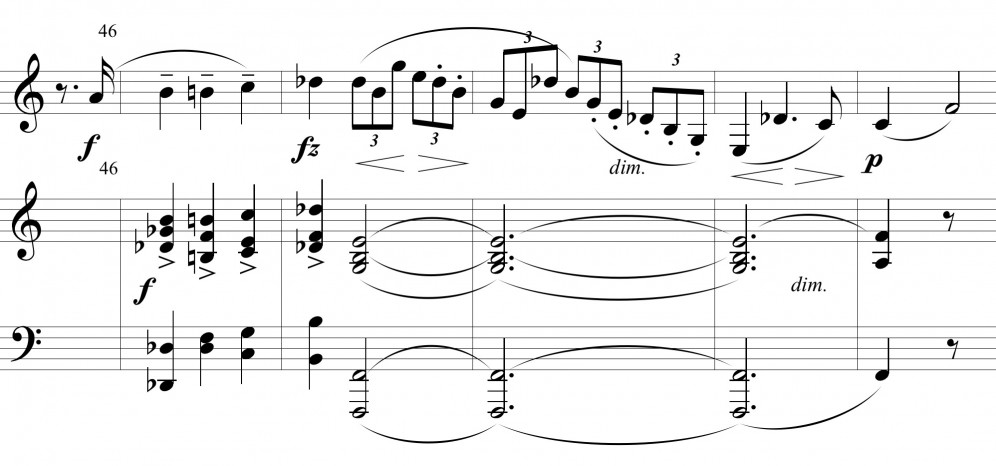

This movement is a thematic ternary form with a coda beginning in measure 41. Following a perfect authentic cadence, we move through several measures that utilize mode mixture (a highly Romantic characteristic). The intensity of the line increases as it moves through measure 46 where we witness the first forte dynamic of the movement. All of this leads towards the downbeat in measure 47, a deceptive arrival. The clarinet outlines a fully diminished seventh chord (Example 2). Here, we have a pause in the action. The performers may treat measures 47-49 in a cadenza-like manner. From measure 50 to the end, the clarinet and piano continue to communicate. The clarinetist should be mindful of the syncopation and use it as a method to respond to the pianist. It is tasteful to have the movement end with elegance.

Example 2

Movement 2

In his original manuscript Gade wrote the second movement in cut time, but in the first published edition it is marked Allegro vivace in common time. We may never know the reason why this was changed but we can perhaps deduce that the composer, at the very least subconsciously, wanted to infer an intention of pulse. In a common time signature the first beat of the measure receives the strongest pulse. The third beat isn’t quite as strong as the first, but it is stronger than beats 2 and 4. In cut time, the pulse is performed “in two,” generally alternating between a strong first beat with a weak second beat. This greatly changes the flavor of performance. Clear examples of when to treat the second “big beat” of the measure as a weaker beat (receiving less emphasis) are seen throughout the movement, especially in measures when the note on beat 3 is tied from a previous note. The first three measures the clarinet performs to start the movement are clear examples of this. There are opportunities in this movement to phrase in such a manner that leads towards beat 3 (big beat 2). Use these occasions to thwart the listener’s expectation.

The second movement clearly contrasts the first and the performers should make this obvious. Articulation can be more pointed. Contrast the themes marked tranquillo and dolce with the more energetic principal theme of this movement. The pianist performs most often in triplets in this movement; therefore the clarinetist should pay attention to when their part is written in duple against triplets and when they are asked to perform triplets in unison. A cohesive and well-planned performance is always paramount.

Movement 3

Ballade is the third movement of Fantasiestücke and it is the most unique. The only movement with its own title, it allowed Gade to create a musical narrative based upon the rich history of Scandinavian folk tales and mythology. This movement offers great contrast within the movement itself and among the four pieces that make up the whole of Op. 43. Performers should take advantage of the opportunity to be highly descriptive and to tell a story.

Scandinavian folk tales include a variety of characters and mythological creatures. Gade no doubt sets the stage for the appearance of the first character in measure 5 with the opening four measures outlined by the piano. He chooses to write for the clarinet in its low chalumeau register, a range that has often captured the imagination of composers due to its rich overtones, earthy sound and generally pleasing timbre. The simple melodies of the clarinet line should be played with some weight in this opening A section, almost sinister. The following section marked Tempo animato offers a more lively character, written in the clarinet’s clarion range. It is somewhat heroic in spirit. Before too long, however, the opening character returns. Following the two symmetrical phrases of the B section, Gade adds an extra three measures of transition in which the opening sinister character signals its return.

There is high drama beginning in measure 52 with an operatic tremolo in the piano. The clarinetist should match the weight of the piano’s low range and use the mf dynamic to their advantage. The fermata on the final note of this section should be long and the performers should consider using the silence of the rest to create a sense of suspense by delaying the start of the next section.

The B material returns at measure 62, marked once again by an animato as well as a scherzando indication. Perform here with an even more playful and dance-like character as compared to the debut of this material. The clarinetist should glide and dance atop the flowing and animated 16th-note passage of the piano. The heroic character is unyielding and challenges the sinister character for supremacy.

Example 3

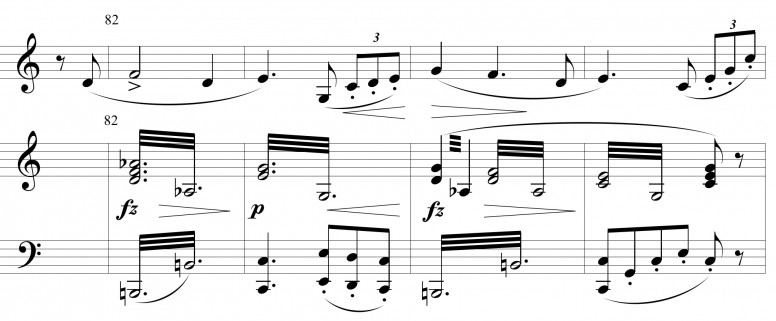

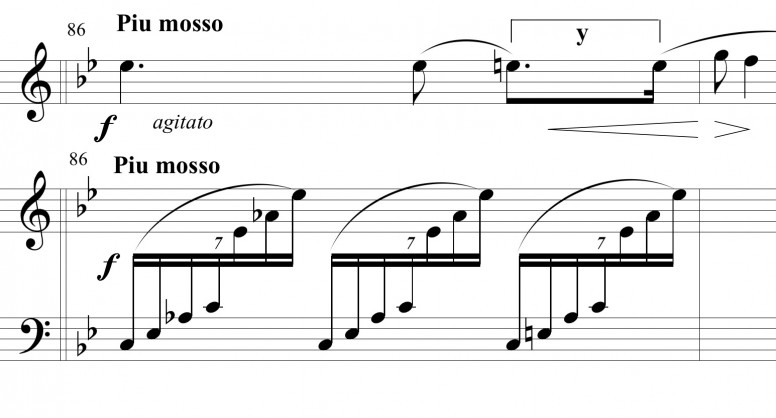

Eleven measures into this second appearance of the B section we see an alteration from the initial B theme. A battle ensues in measure 74 between the “heroic” and “sinister” characters, previously only presented in their own individual sections. Gade marks an indication of con gravita here. The clarinet should play with length and separate any notes marked with an accent underneath a slur. Take note that the clarinet line is marked forte while the piano part is marked at mezzo forte. Gade attempts to compose the back-and-forth nature of a scuffle in measures 82-85 (Example 3) by writing quick changes of dynamic levels in the piano line. The piu mosso and agitato in measure 86 signal the climax of battle. It is interesting that during the first part of this section the clarinet has been performing in the chalumeau and now it quickly leaps to the upper register. The hero has gained the upper hand! In addition to range, Gade further signals a change of fortune for our hero in battle by using the same “y” motive (Example 4) used earlier in the B theme.

Example 4

Following the ruins of battle, all is not well. This is signaled by the final Lento section. Woven within Scandinavian folk tales is a common thread of morality. Positive character traits are praised and rewarded and faults are punished. Gade alludes to hope and peace in the final three measures culminating in a major chord. It is the signaling of the moral of our story.

Movement 4

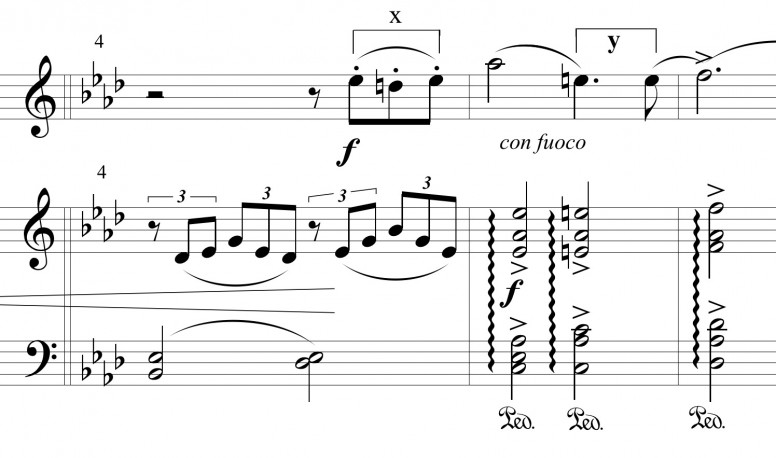

In the final movement we see many of the familiar compositional aspects of earlier movements. Similar use of contrasting sections, familiar stylistic indications (tranquillo, dolce), and repeated motives are used. Immediately the clarinet performs two of the most common motives (“x” and “y”) seen throughout Op. 43 in measures 4 and 5 (Example 5). These motives are employed often in each movement. Indeed, motivic similarity creates unity through the four pieces of Fantasiestücke. This fourth movement is clearly most similar to the second but rather than being marked Allegro vivace it is marked Allegro molto vivace. In addition, Gade writes con fuoco each time the A theme appears, a marking that we have not yet seen. There is more insistence as we approach the end of the work.

Example 5

Fantasiestücke, Op. 43, is a valued work within the solo clarinet repertoire and a charming representation of Gade’s compositional output. Gade often refrains from blatant virtuosity and overt sentiment in his compositions, preferring light drama and charm. He is considered a conservative composer in the Romantic era and his music has a more subtle and internal sense of expression. Never one for grand gestures or strong thematic contrasts, clarity of expression and form remained his hallmark.

About the Writer

Wesley Ferreira is associate professor of clarinet at Colorado State University and director of the Lift Clarinet Academy. He leads an active and diverse career performing worldwide as soloist, orchestral and chamber musician, and as an engaging adjudicator and clinician. Born in Canada to parents of Portuguese heritage, Ferreira received his musical training at the University of Western Ontario (B.M.) and Arizona State University (M.M. and D.M.A.) studying with Robert Riseling and Robert Spring, respectively. He is on the performing artist rosters of Selmer Paris and Vandoren.

Comments are closed.