Originally published in The Clarinet 51/4 (September 2024).

Copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

Master Class

DAN WELCHER’S DANTE DANCES

by Carlos J. Casadó

Read the Spanish Version of this article here: Master Class: Dan Welcher’s Dante Dances (Español)

Dante Dances, composed about 25 years ago by Dan Welcher and dedicated to the clarinetist Bradley Wong, is didactically a very stimulating work for both students and teachers, and of course for any professional who wants to include it in one of their recitals. The piece was written originally for clarinet and piano; however, there is a later orchestral version of Dante Dances also published (rental) by Elian-Vogel (Theodore Presser). According to the composer, the clarinet part is the same, and the orchestral version only augments what was already in the piano part. That said, he was able to make use of sustained sounds in the orchestra that were not possible with the piano, and the new arrangement allowed certain contrapuntal passages to be more highly defined. Some pianistic figurations have been altered to work better with strings. The instrumentation is flute, oboe, bassoon, horn, piano, percussion, and string quintet.

In my opinion, there are two general features that make Dante Dances very attractive. First, it has a relationship with literature, specifically with Robert Pinsky’s translation of Hell, one of the three books—together with Purgatory and Paradise—that make up The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri. This literary link allows pianists and clarinetists to use obvious dramatic elements to shape the story to be told. Second, the suite of dances that articulates the work enables a fresh and active interpretation typical of a ballet.

Against this background, it is essential to read the program notes that the composer writes on the score, published by Elkan-Vogel in 2000. These notes, of great interest, immediately orient the musicians to the challenge they have in front of them. It is interesting to note the author’s commentary on the same series of 12 tones that make up each dance. For both instruments, getting acquainted to this harmonious context will not be easy.

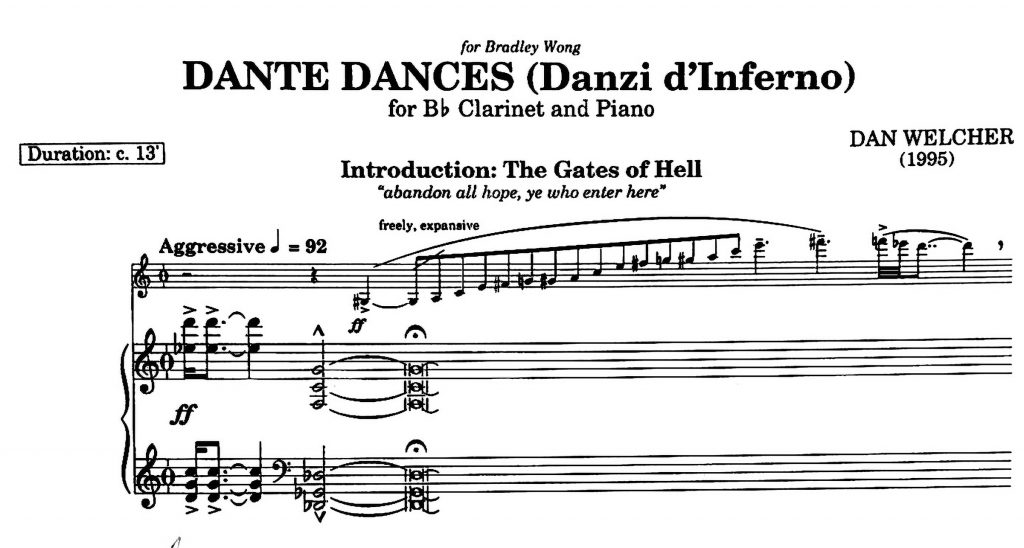

Briefly, the work is a kind of introduction, theme and variations organized into a series of dances, each dedicated to one of the characters who appear on the journey that Dante, accompanied by the poet Virgil, makes to the Underworld. And a trip to Hell is not just any journey. You have to be prepared. As soon as we open the score to “Introduction: The Gates of the Hell,” we read: “Abandon all hope ye who enter here.”

Figure 1: Dante Dances by Dan Welcher (© 1995 Theodore Presser), m. 1

Alea iacta est. In this section I find significant the first indication to the clarinetist: freely, expansive (Fig. 1), inviting them to play with courage and decision (emphasis on the accents), expressing: “Here I am, I am not afraid, let’s go!” However, the second indication: less hurried (Fig. 2), seems to warn the clarinetist to be careful. The clarinetist now sees the journey to Hell as not so easy, starts to feel scared and in a way acts more cautiously.

Figure 2: Dante Dances, m. 2

We must, therefore, show a more hesitant, cautious character, and henceforth take advantage of the color of the chalumeau register, looking for a mysterious sound. We must blow relaxed, looking for the resonance and depth of the timbre.

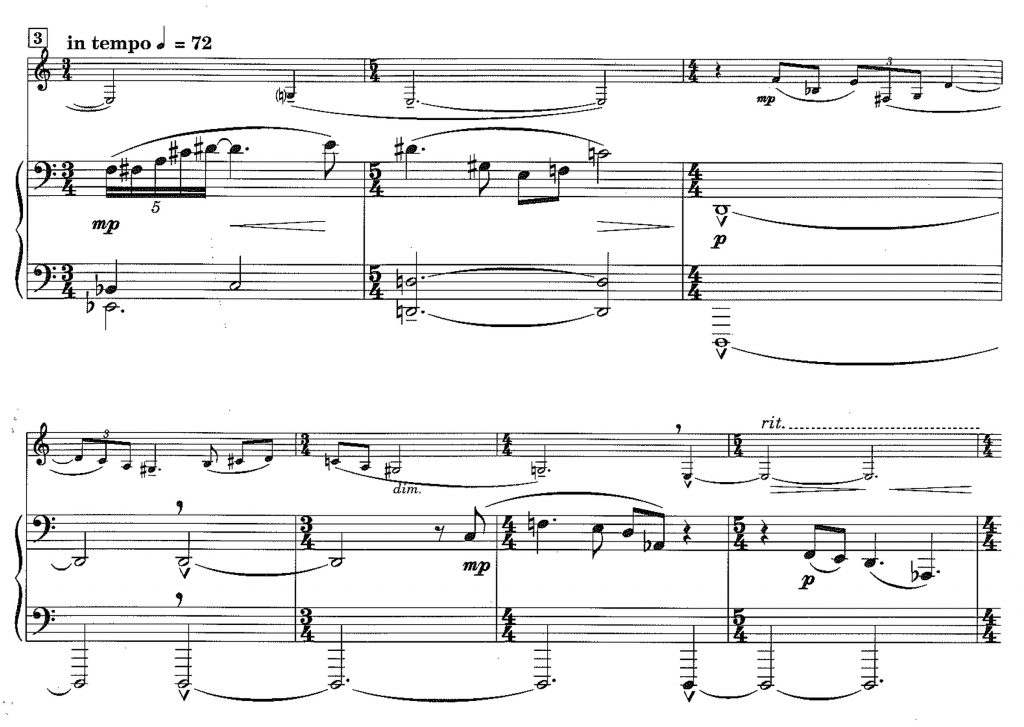

Figure 3: Dante Dances, mm. 3-9

It is important that the interventions of the piano and of the clarinet are linked together smoothly to avoid losing the flow of the music (Fig. 3), in tempo, but as a recitative (pay attention to the commas in bar 5 on the piano and bar 8 on the clarinet), until the moment of taking the boat of Charon, who, represented in the “Tango,” leads us to Hell. The rhythm that we observe in bars of 4/4+9/8 resembles the movement of the oars, with some impulses more regular than others, as an image of the labor reluctantly done by the unpleasant, grumpy boatman as he takes souls to Averno.

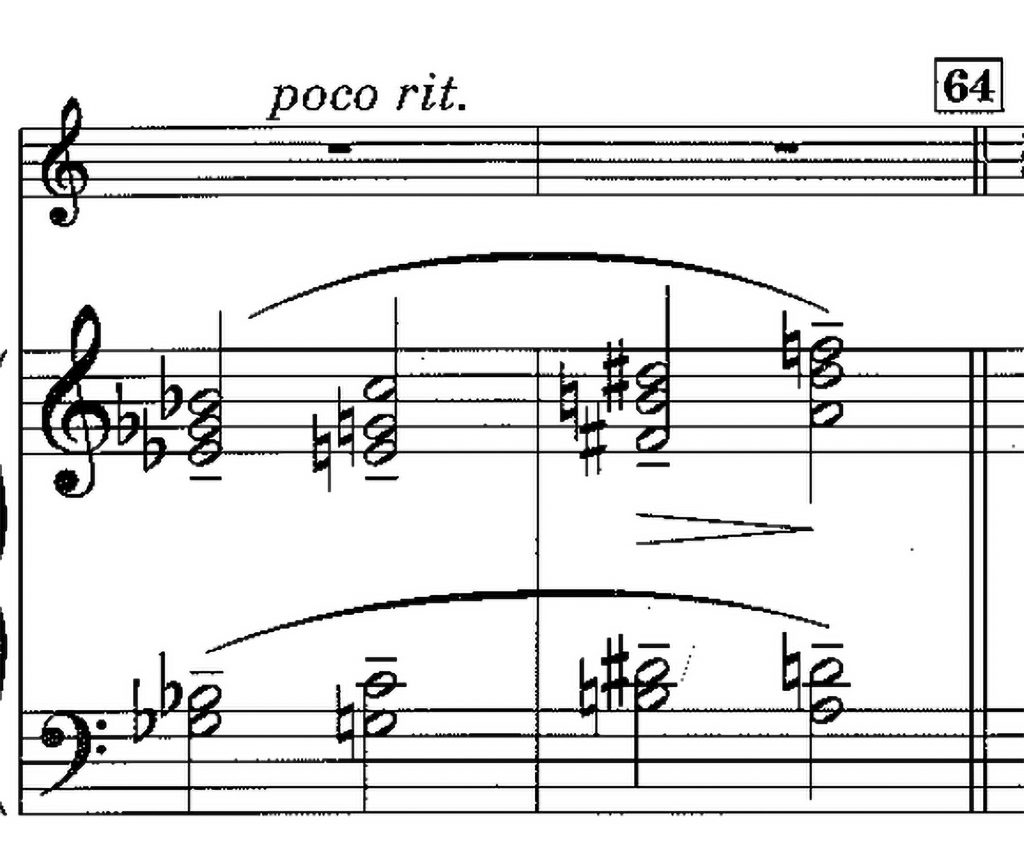

The rhythm that we observe in bars of 4/4+9/8 resembles the movement of the oars, with some impulses more regular than others, as an image of the labor reluctantly done by the unpleasant, grumpy boatman as he takes souls to Averno. Take care to play the triplet figures in the correct tempo, not too fast, not too slow, listening to the rhythm of the piano (Fig. 4). The indication sinuous (bar 22) is the key to understanding the sonority we must employ: in this case, very flexible, with a good legato. We are on the water! The final bars of the piano solo (bar 60-61) anticipate the rhythm of the next dance, but the harmonies of the minims (bar 62-63), which we already heard in bar 10-11 (pure, clear) warn us of something (Fig. 5). Suspense. Careful, Cerberus is there, the fearsome beast that guards the gates of Hell, keeping the dead from coming out and the living from entering.

Figure 4: Dante Dances, m. 39

Figure 5: Dante Dances, mm. 62-63

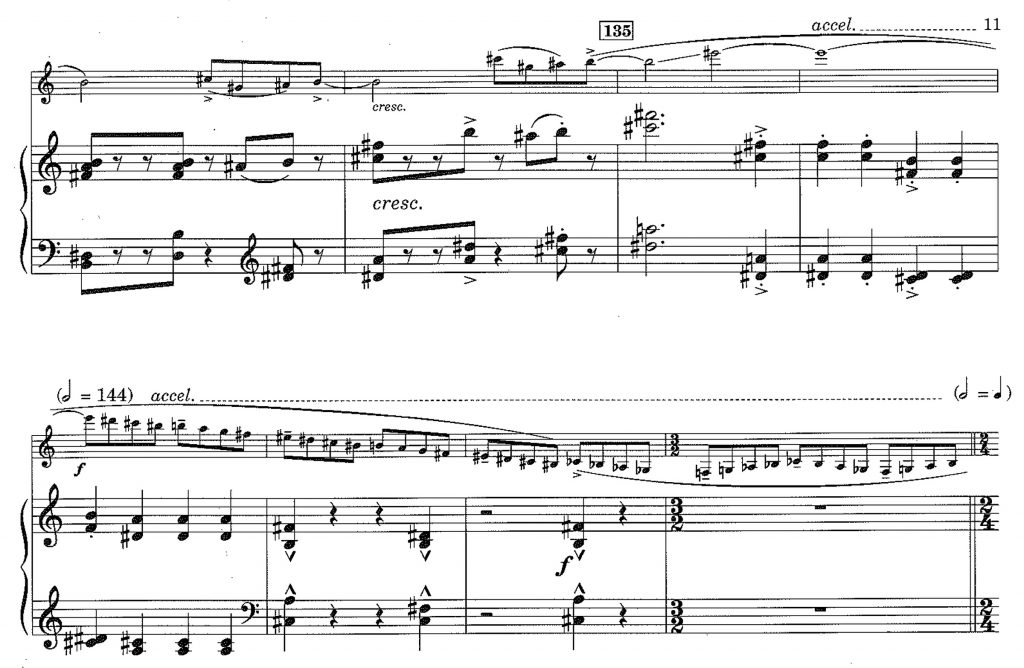

Cerberus is described as a terrible black dog with three heads, snakes protruding from his body, and a serpent’s tail. Represented by a Charleston (listen to Cecil Mack’s “The Charleston” to hear the character of this dance), it is important to highlight the accents, imitating the barking or attacks of the dog. Observe the indications of gaining momentum and rushing, which can illustrate the races of the dog chasing the fleeing souls, and the glissandi as their cries of terror. We can play the passage bar 91 to 110 more calmly and really piano where indicated. For me this is when we are trying to furtively sneak past the beast Cerberus. Bar 135 requires decision; it is the last chance to escape Cerberus. The accelerando and the forte must be desperate, however, the clarinetist must be careful to keep the embouchure firm and to produce a compact sound, without cracks (Fig. 6). The danger does not cease, because the composer condemns us to the torment of the Furies, which chase after those who do evil deeds, until they drive them crazy.

Figure 6: Dante Dances, mm. 135-140

The Polka dedicated to the Furies is frenetic—furious, breathless, indicates the composer. For a moment, the clarinetist gives a truce (bar 148). While the pianist repeats the accompaniment ad lib., the clarinetist can recover energy for the coming battle, and even perform some theatrical gestures to help understand what awaits them. It is important to emphasize that for me, the accents are blows, stabs, burns or any other kind of torture that we can imagine. Play the glissandi like screams of madness, and the trills should be electric. Bars 178-179 are especially difficult technically, where the accentuated sounds must be produced with precision. Relax the jaw a little and put a lot of air on the low note.

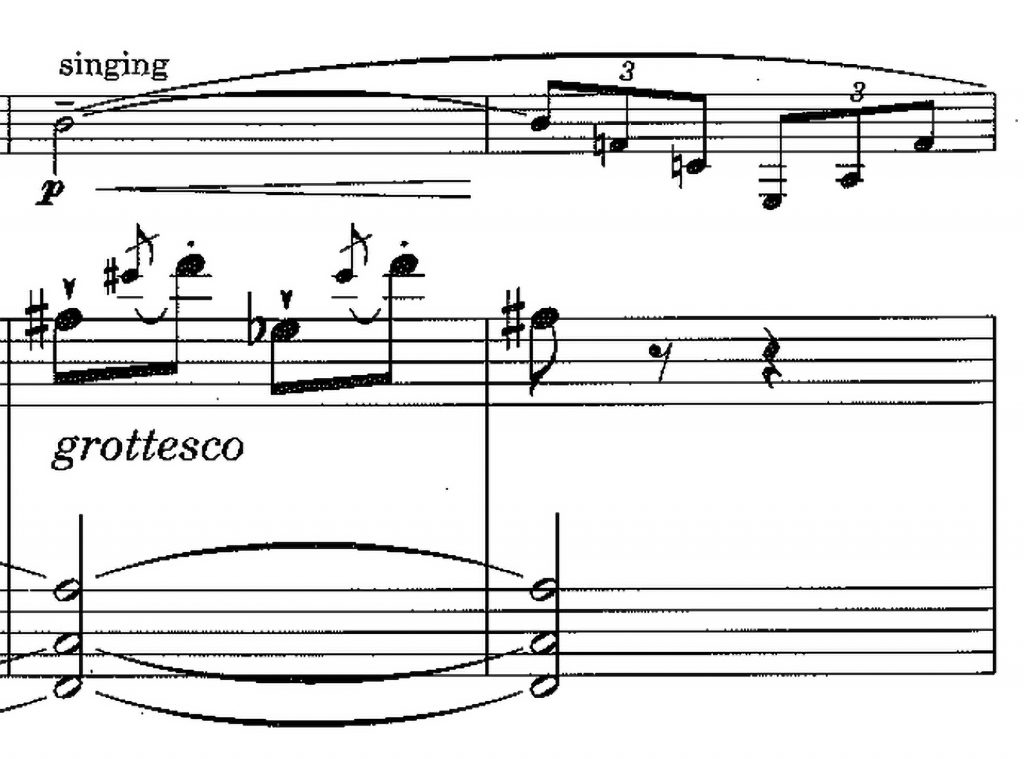

It is important to understand the section of bar 204, singing on the clarinet, but grottesco on the piano (Fig. 7), as bizarre and eccentric. In my opinion we must achieve that on one hand the clarinet sings a caricature song, while on the other hand the piano makes fun of it. Exaggerate the crescendi and diminuendi and be very precise rhythmically in the notes marked for emphasis. The “Polka” loses energy in its final part. We really should take advantage of this moment; the music gives us a respite and the “Gymnopèdie” offers us a moment of calm.

In bar 241 we hear insinuated, first by the piano and then by the clarinet (bar 242) the motive of the theme of Paolo and Francesca, lovers at the mercy of their passion, who in the underworld are also dragged at the mercy of an infernal whirlwind. It’s important to know this because the score reflects very well the first of the emotions. On the one hand, the rhythm of the “Gymnopèdie” (bar 243 on the piano) and the indications on the clarinet in bar 252, sweetly and sadly, suggest the pair letting themselves be swept away sweetly by the outpouring of love, but languishing, sadly, from the consequences of it. It is therefore necessary to pay attention to the figuration of the piano and that intoxicating swaying. We must contain the emotion, search for a dolce sound (playing above the notes) but with some outburst of passion (bar 269-272 are rich, sensuous). Both instruments must find different colors in the sound in bar 278 to 295, especially in the long notes of the clarinet, in bar 278-280 and bar 292-294 (Fig.8). Try to change the air speed to find subtle colors and shades, in short, to be expressive with your sound and create something really beautiful.

Figure 7: Dante Dances, mm. 203-226

Figure 8: Dante Dances, mm. 292-294

Dante has great respect for the great traveler of antiquity, Ulysses, for Ulysses has made multiple journeys while Dante is just beginning his journey beyond the grave. Ulysses recounts that his “inner ardor to know the world, the vice and virtue of humans” impelled him to explore the world with a simple boat and a few faithful followers who never left him. But Ulysses is punished for his pride and condemned to Hell for his unbridled eagerness for knowledge and adventure.

This narrative character, of something that is in motion, is represented by the “Schottische” (YouTube provides a good reference for this dance). Once again, the author’s indications in bar 311 (perky, very crisp) are very inspiring. The most important thing in the clarinet part is the different types of articulation written, and each one of them must be followed very accurately. On the other hand, listen well to the piano part, particularly when we perform the trills, because it will help us to keep the tempo, propelled again in bar 365-366 by the quarter notes of the piano and the accents of the clarinet on the trills (Fig. 9), to reach the “Prestissimo! Tarantella,” dedicated to Gianni Schicchi. Dante makes a short reference to Gianni Schicchi in his Comedy, famous for his capacity for impersonation of people, for which reason he is in Hell. Puccini wrote an operatic trilogy inspired by some episodes of the Divine Comedy, with Il Tabarro, Suor Angelica, and Gianni Schicchi, corresponding respectively to Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise of the Divine Comedy. However, the reference to Schicchi in Welcher is diabolical, not comical like in Puccini. With fast tempo, the whole “Tarantella” requires from both instrumentalists technical agility and a light articulation, especially in bar 443 (whispering).

Figure 9: Dante Dances, mm. 365-366

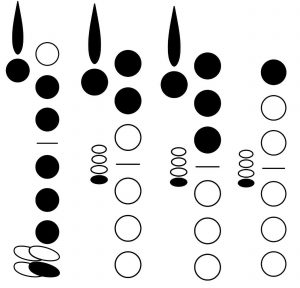

Figure 11: Recommended fingerings for the end of Dante Dances: B-flat in m. 490; F-sharp, F-natural, and D-flat in m. 498

It is important to hold the tempo even on the bars of silence 441-442 and in bar 461 specifically, for it is surprising how the composer articulates the rhythm of the dance with the lyricism of the melody of Paolo and Francesca (Fig. 10). Singing clearly, rich and full… dancing: a brilliant moment. In bar 490 the clarinetist may employ a position to get the BÌ from the DÌ simply by adding to it the ring and little fingers of the right hand. And in bar 498 the high FÏ can be played as a harmonic of clarion BÌ, FÓ by adding the ring finger of the left hand and the DÌ with the index finger of the left hand and the lowest right-hand trill key. Both instruments should keep the fortissimo until the end of the scale and then the piano up to bar 9, finishing with a subito ff. End of journey.

Figure 10: Dante Dances, mm. 461-478

Carlos J. Casadó is currently second and EÌ clarinet in the National Orchestra of Spain. He is professor on leave of absence from the La Coruña Superior Conservatorio of Music. In addition, he has completed studies in sociology and psychology of music. He recorded Dan Welcher’s Dante Dances along with other works for clarinet and piano with pianist Damián Hernández on Musica Entre Historias (2018).

Carlos J. Casadó is currently second and EÌ clarinet in the National Orchestra of Spain. He is professor on leave of absence from the La Coruña Superior Conservatorio of Music. In addition, he has completed studies in sociology and psychology of music. He recorded Dan Welcher’s Dante Dances along with other works for clarinet and piano with pianist Damián Hernández on Musica Entre Historias (2018).

Comments are closed.