Originally published in The Clarinet 50/4 (September 2023).

Printed copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

Reprints from Early Years of The Clarinet: Pedagogy

This special reprint section explores the teaching of Daniel Bonade, Simeon Bellison, Ralph McLane, Kalmen Opperman, Leon Russianoff, and others. These excerpts from articles and interviews are followed by commentary from some of today’s ICA country chairs about clarinet pedagogical traditions throughout the world.

coordinated by Rachel Yoder and Caitlin Beare

The Bonade Legacy, Part II

Jerry Pierce, one of the last of Daniel Bonade’s students, contributed the article excerpted here to The Clarinet 4 no. 3 (January 1977). Pierce later served as president of the ICS from 1980-1986.

by Jerry Pierce

Daniel Bonade

BONADE’S CONCEPT OF CLARINET PLAYING

It was Bonade’s opinion that the perfect musical instrument was the human voice: therefore, his approach to playing the clarinet was to always make the instrument “sing.” He abhorred the clanking of keys or the banging of fingers on the tone holes when playing the instrument. These were all non-musical sounds that one spends a lifetime overcoming. Perhaps he himself never overcame the mechanical aspects of playing but he e the listener think that nothing was technically impossible for him. Whenever he played it looked so easy. He was never satisfied with his own performances and in this respect instilled in his students that never-ending search for perfection (a goal in playing which could be approached). He stated that he had never been able to play the way his mind’s ear had thought a clarinet “could” be played but maybe his students would some day be able to.1

He withheld nothing that he knew in teaching his students. Each question was answered and problems corrected. Bonade had a very analytical mind and found solutions to many problems that prevent beautiful playing.

He was an exponent of complete control over the fingers while trying to relax. Almost always when a new student would come to him for instruction he would have them start with number one of the C. Rose Forty Studies to gain complete control over the fingers.

First, one would have to do bar eight in slow quarter notes lowering one finger at a time from a high position with continuous motion once the finger started down. In the beginning if a gliss resulted it was tolerated as smoothness was the important goal in descending passages. For ascending, the air (and thus the dynamics) were increased on the lower note to give the impression of smoothness in leaps. Next, bars four and five were treated with the same thoroughness, and finally bars one and two, which he considered to be two of the hardest bars in the clarinet literature to play smoothly.

It would appear that Bonade taught a very high finger motion for slow playing but in reality he insisted on the fingers not raising too high as control developed. In the end the fingers were only raised high enough off the keys so as not to affect intonation. He dubbed this style of playing the “legato fingers” technique.

At the same time that the smooth playing was being undertaken the aspect of articulation was under inspection. Etude number eleven, again in the Rose Forty Studies, was used for the study. The first note of the slur was held full value and accented. The last note of the slur was clipped, whereupon the fingers had to move immediately to the next note but the student had to wait for the moment to play the staccato note. So it went: “TAT – MOVE – WAIT TAT – MOVE – WAIT” very slowly with both the staccato notes very very short and the finger action exact and quick.

As the speed increased only the time between the staccato notes got shorter. The notes themselves were already as short as possible and the fingers were already in their new position, having moved immediately after playing the preceding note.

In theory Bonade had developed a way to play notes in connected staccato passages as fast as repeated staccatos on a single note. He used the Forty Studies of Rose as the work book and the Thirty-Two Studies of Rose as the “Bible” for correct phrasing with each of the slow etudes treated as a slow movement of a concerto.

In teaching phrasing Bonade would insist on an exaggeration of dynamic contrast. He would ask for 200% from his students and assumed that the player otherwise would only produce about one-half of what he was capable.2 He expected the student to develop a smooth, beautiful legato with perfect control, and yet also possess a lightning articulation and a blazing technique which he felt was achieved through slow careful practice.

Bonade never skirted technique and expected an advanced student to be able to play any passage in any key at about any speed. Thus, the etudes of Jean-Jean, Baermann, Stark, Cavallini, Perier, etc. were thoroughly studied in addition to the solo literature for the instrument.

Bonade has said,

“Technique is everyone’s playground. ‘PHRASING’ however, belongs to those who can concentrate on the meaning of music, who are willing to work and who have achieved all the requirement of fine playing: that is, beauty and flexibility of tone, perfect control of finger action, comprehension of musical line and feeling for interpretation.”3

Bonade’s knowledge of reeds is legendary. He only used a piece of dutch rush, a small piece of plate glass which was attached to the outside of his old-time reed case (which held four reeds), an emery board, and his reed trimmer. He told me that his early teacher, Capelle, used to trim reeds with scissors but later Lefebvre loaned Cordier the money to start manufacturing reed trimmers. In appreciation Cordier gave Lefebvre the first one and Bonade the second.

Bonade liked a free-blowing set up. He expected the reed to speak at a pianissimo with little effort (that meant the tip of the reed was soft enough) and yet be able to stand up to a true fortissimo (which meant that there was enough “wood” in the “heart”). He preferred a reed that had “buzz” or “ping” as he called it, because that meant the reed would carry well.

He was not overly concerned about the clarinet sound at close range. He thought that most second players probably wanted the first chair position and so there was no reason to please them. The conductor and the audience were the important judges to please and so his concern was the sound that they heard.4

He had the knack for making about any reed play beautifully and could explain to his students how and why he was adjusting the reed a certain way. He believed that the right side of the reed should be a trifle softer than the left side because, as he explained, the right thumb supports the instrument and therefore more pressure of the lip is unconsciously put on the left side of the reed. He would use his thumb nail to flex the tip and rails of the reed and determine where the reed needed to be altered and then would proceed to make it work beautifully for the student that day.

In addition to publishing a booklet in 1947 entitled Manual of Reed Fixing (which was later published by Leblanc in 1957 as The Art of Adjusting Reeds and is currently available in A Clarinetist’s Compendium, 1962, also published by Leblanc) Bonade wrote many articles on reeds in the professional journals.5 For a time “Daniel Bonade’s Reed Notebook” appeared in The Clarinet (James Collis, the editor, was a former student). [The Clarinet here refers to the 1950s publication by Symphony, not related to the ICA publication. Ed.] Bonade also wrote a column for the old Symphony magazine called “Scoring for Winds.” Some of the articles later appeared in The Clarinet and Woodwind World.

In these articles Bonade covered many facets of artistic clarinet playing and making music. During his tenure with Leblanc he also contributed a column called The Clarinetist’s Corner for The Leblanc Bandsman.

It was Bonade’s desire to share with other clarinetists all that he knew in hopes of advancing the art of clarinet playing. To this end he worked increasingly through his teachings and writings, and his own sacrifices of time, sometimes money, and health were a small price he felt he paid for helping others.

Endnotes

1 Statement by Daniel Bonade at a private clarinet lesson. New Hope, Penn. January 2, 1959, 4:00 p.m.

2 Daniel Bonade, “The Clarinetist’s Corner,” The Leblanc Bandsman. Vol. IV, No. II. (January, 1957), p. 6.

3 Daniel Bonade, “The Clarinetist’s Corner.” The Leblanc Bandsman. Vol. V, No. II. (December, 1957). p. 8.

4 Statement by Mitchell Lurie at the International Clarinet Clinic. University of Denver, Colorado. August 14, 1974.

5 Daniel Bonade, Manual of Reed Fixing. (New York: Bonade-Falvo-Pupa Corp., 1947); Daniel Bonade, The Art of Adjusting Reeds. (Kenosha. Wis.: G. Leblanc Corp., 1957; and Daniel Bonade, The Clarinetist’s Compendium. (Kenosha. Wis.: G. Leblanc Corp., 1962). pp. 13-16.

The Good Old Days

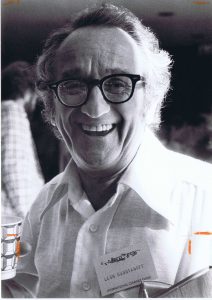

Lee Gibson was the first editor of The Clarinet and president of the ICS from 1978-1980. For vol. 5 no. 3 (Spring 1978) he interviewed Leon Russianoff, vice president of the ICS (1973-76) and influential teacher of Stanley Drucker, Charles Neidich, and many others as professor at the Juilliard School and the Manhattan School of Music.

by Leon Russianoff as interviewed by Lee Gibson

Leon Russianoff

Lee: Tell me something about your teachers.

Leon: My first teacher was a wonderful, but elusive moving picture, vaudeville, and fiesta musician of Italian descent. He came to my house to give me lessons. I said he was elusive because very often he just didn’t show up and it was always because he had had a ‘flat tire.’ He must have blown twenty tires a year.

He played Albert system clarinet and used five reeds per annum. He scraped them with a dull razor blade and miraculously they always played for him. He was responsible for my first playing and drinking experience. He took me with him on his ‘Italian-feast’ jobs;—three bucks for the day plus all the spaghetti you could down and all the vino you could swallow. The band would parade through the community, collect some money and plenty of Chianti at each stop. At the end of the day the marching band no longer marched. We staggered and lurched to our destination.

The musical high-point was the evening concert which always consisted of the Poet and Peasant overtures and fantasies from Rigoletto and Aida. I didn’t know any better so I was able to knock off all the cadenzas and solo parts with ease.

I got a N.Y. Philharmonic Society scholarship to study with Mr. Simeon Bellison. I felt very guilty and disloyal when I left Mr. Dominic Tramontane.

Lee: Mr. Bellison is a legend. How did you “experience” him? What kind of teacher and person was he?

Leon: That’s an easy one. He was a great man, a person of enormous personal dignity and charm, an unparalleled artist, interested, fair, and non-judgmental. Indeed, when you were with him you felt that you were in the presence of a great man. His special quality as a teacher was his ability to transmit to you his respect for the music. The emphasis was always on character, style, and phrasing. He left little to your imagination, however. You were told how to play. Every nuance, every contrast, ritard, and accent was carefully marked in the part. While this approach did not particularly engender individuality and personality, it did make you very aware that music was character and feeling, not merely technical accuracy and proficiency. I would strongly recommend as study and performance material all of those solos and transcriptions he taught us: Concerto Rondo by Mozart, Variations on a Theme by Mozart by Beethoven, Russian Dance by Tchaikovsky, and Fantasie from Der Freischutz by Kroepsch. These and others are all published by Carl Fischer. They are delightful and successful solo pieces and are very developmental.

Bellison was our idol. It was inspiring just to be in his presence, the solo clarinetist of the N.Y. Philharmonic. Kalman Bloch of the Los Angeles Philharmonic was his outstanding pupil. At the lessons Mrs. Bellison was very much in evidence, looking after him, bringing him tea, and sometimes having to remind him ‘Simeon, the time is up.’

It might be interesting that Mr. Bellison demanded that we play with very strong, heavy, and indeed stiff fingers. We all tried to imitate his beautiful sound and at one time or another took a crack at playing a German mouthpiece with a pine board for a reed. None of us could make it with the German setup. While Mr. Bellison did not tell us much about embouchure, reeds, mouthpieces, baffles, chambers and facings, somehow, as I recollect, most of us got a pretty good sound. We used the Woodwind mouthpiece with either K.7 or the G7* and 8 facings with Vandoren reeds which were then ungraded and cost $3.00 for a box of 25.

Lee: What about Mr. Bellison as a performer?

Leon: He was superb in the orchestra especially when it came to playing very short phrases as in some of the Brahms symphonies. It was a big sound somewhat like Karl Leister’s.

In those years a solo, or even chamber music, by a clarinet player was a rare event, even for someone with the status of Mr. Bellison. I recall that when he played his mouth would get dry and he would have a bottle of some liquid (water, I presume) tucked into the breast pocket of his jacket with an inconspicuous rubber tube leading to his mouth. Every once in awhile he would take a gulp.

…

Along the way I studied with Daniel Bonade, by then the most famous teacher after his great career in the Philadelphia and Cleveland orchestras. Whereas Bellison had taught hard, brittle finger action, Bonade emphasized the lightest possible touch. I eventually came to feel that it didn’t really matter that much. The only time that I will stress relaxation in the fingers is to achieve a relaxed and non-pinched embouchure.

…

Lee: Did Stanley Drucker begin as a violinist? When he raises his clarinet and his hands the preparatory gestures all seem to be those of a violin virtuoso.

Leon: No. He started on the clarinet at the age of 11. As his teacher, having spotted a great talent, I was smart enough to keep out of his way. As a youngster he wasn’t too enthusiastic about scales and drills. We got around that by assigning him a book a week: January 3, 1947 (?) all of Rose book 1. January 10 all of Rose book 2, and so on. After having taught Stanley many years I must confess that when I heard him for the first time in an actual performance I could hardly believe that this was the young man I had worked with as a child.

Lee: You have attended perhaps six of the annual International Clarinet Clinics at the University of Denver. What brings you back?

Leon: Most importantly going to Denver gives me the opportunity to shed the provincialism I mentioned earlier in our talk. The wide variety of sounds, concepts and styles is very enlightening. And as you may well know I have a personal vendetta with the ridiculous notion so prevalent in the Midwest about the so-called New York sound so terribly exemplified by myself and some of my students. This is reputed to be, against all evidence of aural sensibility, a rough, rowdy, raucous, reedy, and unrefined sound. Not at all like the lush round tone produced in the rest of the country and most especially at the Paris Conservatory. Many of my colleagues who have heard some of my students perform were surprised when they did not hear the kind of ugly playing they had been led to expect. I have collected all the tapes of all the clinics I’ve attended and can indeed document these assertions.

I also dig the competition of the young clarinetists, the daytime recitals of some of our artist-professors, Gerry Errante’s avant-garde genius, performances of the solo artists at night, the profound hallway discussions of mouthpiece dimensions, reed knives, Dutch rush, etc. But above all I am enthralled by the universal search for an ‘old Chedeville mouthpiece.’

Everybody at the clinic is gungho. You meet people like John Denman, a great player with a really delicious sense of humor. If you ask John why he practices he will tell you he loves it and you know he means it. I must mention also the thrill of hearing our great women soloists, Michelle Zukovsky and Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr. The clinic is for me a happening, a place of idealism and inspiration. I feel that I grow musically and personally each time I go.

Lee: What would you tell clarinetists about equipment?

Leon: I would advise them not to spend too much time on carpentry, on measuring and experimenting. There is no one mouthpiece, no one reed, no one instrument. Find a good mouthpiece, find a good reed, test what’s available, but at sometime try to be content with and oblivious to your equipment. Play whatever is right for you.

…

Lee: What about the relative performance standards of our youth in the present day?

Leon: There is no question in my mind that the standards and the quality of clarinet playing today are infinitely higher than ever before. The teachers are super-qualified. The schooling is superior and the number of dedicated student-artists is legion.

Lee: You frequently mention Simon Kovar, the teacher of so many of the finest bassoonists.

Leon: Not only was he the greatest bassoon teacher I have known, but he taught artist-players on all instruments. He helped me enormously and I have incorporated many of his ideas into my teaching philosophy.

Lee: What is your philosophy of teaching?

Leon: Teaching and learning are one and the same art. Since I married Penny there has been a profound change in my learning and teaching style as well as in my behavior as a social person. As you know, she is a great psychologist and she taught me to feel good about myself, to feel worthwhile, and to be proud of being a clarinet teacher. Through her inspiration I went, in five years, from feeling like Casper Milque-toast to Napoleon. The learning and the teaching process starts from and grows with affection. Now I’m more into loving my students. We must enjoy our lessons. When a student calls to cancel his lesson because he’s not prepared I tell him to come anyhow. These are often the very best lessons. Too many lessons, in my view, are prepared performances at which the teacher functions as audience and general critic. An unprepared lesson gives you the time to attack some hidden problems. If I may sum up, teaching must be a “labor of love” (for a substantial fee of course). If you have contempt for your student—if you feel superior to him or her—if you are competitive with him—if you lay all the blame on him or her—if you encourage their natural impulse to accept guilt—you will probably exert a very negative and unhappy influence. I cannot deny that there are a few teachers that I know, who never encourage, never praise, never enthuse. The best they can muster is a reluctant “you’re just beginning to get the idea,” “that was not too bad” or some such diffident comments, that do get good results. This surprises me but I cannot deny the evidence of my senses.

Lee: What, then, constitutes greatness in teaching?

Leon: This is a personal view. Given complete professional qualifications greatness follows real love for the student and for teaching. The “putdown” must be replaced by the “BRAVO.”

…

Lee: What is the most important advice you can offer a clarinetist?

Leon: Perform whenever you can. Solos, an evening of chamber music, a rehearsal, any kind of performance is more growth-inducing than several hours in the solitary confinement of the practice room.

An Interview with Kalmen Opperman

John Bruce Yeh, longtime clarinetist with the Chicago Symphony, spoke with Kalmen Opperman and Richard Stoltzman for The Clarinet 22 no. 3 (May-June 1995).

by John Bruce Yeh

Kalmen Opperman, Richard Stoltzman, and Louise Opperman

Kalmen Opperman was born in New York City on December 8, 1919, and raised on a farm in Spring Valley in upstate New York. The son of music-loving parents, he began clarinet studies at the age of 11. In his teens he studied with Simeon Bellison, principal clarinet of the New York Philharmonic. By the age of 19, Opperman had enlisted in the United States Army, joining the West Point Band, and shortly thereafter began a very influential six-year period of study with Ralph McLane.

Upon discharge from the Army, Opperman began a career spanning nearly 50 years playing in the orchestras of Broadway musicals. He was also principal clarinetist of American Ballet Theatre, Ballet de Paris, Ukrainian Folk Ballet and played in commercials, radio, television, etc. During this time, his name became known world wide as a distinguished author, renowned pedagogue and master craftsman. In 1952, he published his first volume of Modern Daily Studies for the Clarinet, followed by Books 2 & 3. In 1956 Opperman completed his Handbook for Making and Adjusting Single Reeds, the first authoritative book on clarinet reedmaking. And in 1960 his Repertory of the Clarinet was published by Ricordi (Italy).

On July 11, 1994, the eve of ClarinetFest, Bruce Duffie of WNIB Fine Arts Radio in Chicago and I spent a fascinating evening with Kal Opperman, his lovely wife Louise (Wee-Z) and Dick Stoltzman. Following is a transcript of excerpts from the conversation that took place:

JOHN BRUCE YEH: Where did you get your start, Kal?

KALMEN OPPERMAN: I was raised on a farm.

BRUCE DUFFIE: …a clarinet farm. [laughter all around]

KO: Upstate New York. My father was a flutist, but lost his teeth very early so his sound was airy. You could tell he was a good flutist at one time. There’s where I began the serious study of the rudiments of music and clarinet playing. He used to say, “Before you go to the bathroom, you get your chromatic scales in.” — you know in the morning, first thing. It was very European.

JBY: Was he from Europe?

KO: Yes, Vienna. Then diatonic scales, majors, minors, then chord sequences — that was the beginning of your day. I said, “Why do you have to play so much?” He says, “You want to be a clarinet player? See that guy outside digging that ditch? He does eight hours!” Then father said, “Back in the room!” …

JBY: So, what about your earliest training as a clarinetist? You mentioned Bellison.

KO: No, before Bellison came a little Italian guy, Mr. Crapulli, a fine, fine clarinet player, and he played double-lip.

JBY: Hm! Was he in your town?

KO: No, he was in New York. I was then 13 or 14, and I was asked to play at an Italian feast. I never did that in my life. I went there and here’s this guy playing so beautifully, double-lip, you know. And I said, “Gee — the kids in school don’t play like that!” See, I always felt different because I played double-lip.

JBY: Did you just pick it up on your own, by instinct?

KO: Yes, I asked my father, “How do you do it?” He said, “Oh, put the clarinet in your mouth.” Boom, I put the clarinet in my mouth and that was it! “Thu, thu thu.” He was a flutist. What did he know about a clarinet? So then I went to Mr. Crapulli. He said, “Who teach you like this?”—you know, the double-lip. I said, “Nobody. I just do it like that!” …

JBY: How long were you with Bellison?

KO: About four or five years.

JBY: Can you describe your study with Bellison?

KO: It was very routine, academic in a manner of speaking. But what I got from Bellison… He said, “Oh, you got technique. You don’t have to practice like that. No, no, no. You better play…” I want to tell you something — that guy made more music, just beautiful musical phrases — great musician. He wasn’t a staggering player in the technical sense, but boy did he make music! Never a note came out of his horn that didn’t sound like it belonged there — everything in place — a bit like Heifetz. …

JBY: In your studies with Bellison, did you ever come across any other of his pupils when you were there?

KO: Oh my gosh, yes!

JBY: Who were your contemporaries?

KO: Well, Benny Goodman — he used to come in, sit down and listen to my lesson.

JBY: He used to sit in on your lessons? How was that? Was he the “King of Swing” yet, or was he just another student?

KO: God, was he! Was he ever the “King of Swing.”

JBY: Is that so?! And he’d go to Bellison?

KO: Sure he did, every time the band was in town.

Richard “Dick” Stoltzman: He came to your place.

KO: Yes, you [Dick] and I were playing some technical duets, really moving like hell. Benny’d say, “Boy, you sound like two chickens!” Ha, ha, ha!!

JBY: Did you ever hear him play for Bellison?

KO: Sure.

JBY: What would he play?

KO: He’d play “legit” stuff.

JBY: The Mozart Concerto?

KO: Yup, that and Brahms. He’d play the sonatas, Trio — played the Quintet.

JBY: And Bellison would coach him? Sing to him, bring it out of him? That must’ve been fascinating to witness!

KO: It was! Sure. I asked him if I could stay. He said, “Yeah, but I don’t think you’ll learn anything.” That was Benny! Ha, ha, ha!

JBY: What repertoire did you play in your lessons with Bellison?

KO: I didn’t study the repertoire. I did that on my own.

JBY: Aha. So it was routine, like you say.

KO: Absolutely. It falls into another one of my classical “theories” — you can’t teach music. You can teach the instrument.

BD: So, it’s just pure technique, then.

KO: Not just technique, it’s a way about the instrument. There’s a sound. You hear a sound. You’re gonna try to get that sound. You’ll shoot at it even if it kills you — might destroy your playing or whatever — but you’ll shoot at that sound. It’s in each of us. The little thing I said before, you know, “the sound you really hear, you never forget. It’s always in your mind.”

JBY: So what would you go through in weekly lessons with Bellison?

KO: Oh, we’d go through scales, we’d go through chromatic scales, we’d go through his chords, you know his book, book of scales. And then you’d do the chords and then you’d do Kroepsch. You’d go through all the Baermann books. And then you’d once in a while get a solo. …

JBY: Did he ever go over any orchestra repertoire with you?

KO: Only if I wanted to. And I didn’t want to. I didn’t need it. I was a clarinet player when I was young. I could hear something and then I could figure it out myself — because you have to teach the kid how to do a staccato. What the hell is he doing with Midsummer Night’s Dream if he can’t staccato? He’s gotta get 88: [Sings Midsummer Night’s Dream Scherzo] Well, if he can’t sing it, how the hell is he going to play it? That means he can’t hear it. You gotta stuff that stuff in your head!

BD: Teach the technique first — then you can impose it on any music that’s in front of you!

KO: That’s right. Now, we’re assuming that you have some musicality — the extent of which will come out much better if you are a master of that instrument! Well, this is what I teach. I teach you to master that horn.

JBY: Did Bellison teach you to master that horn?

KO: Sure, basically. But then the rest was McLane. …

JBY: So, how did you run into McLane?

KO: Heard him on the air one night when I was in the Army. And I called him up — looked up his address, looked up the number.

JBY: How did you know it was Ralph McLane on the air? Was it a solo?

KO: Didn’t know who it was. I called the station and asked them who the clarinet player was. They said, “Well, we have three or four. Which one would you like?” Ha, ha. “Well I want the first one — the guy who played first last night!” …

So here’s how we [McLane and I] started: “Play a chromatic scale.” I played (doodledoodledoo … one octave). He said, “That’s a chromatic scale?” I said, “well, yeah…” He said, “Well, yeah, it’s chromatic … Like this: one, two” [rips fast up scale]. I never heard one finger out of place, nothing! Ooh. He said, “Where are you going?” I said, “I want to write down a thing or two.” He said, “Don’t do that here! It goes here [points to his head], not on the paper. It goes here! First there, then here [fingers].” My god, I couldn’t believe what I heard. I watched the fingers. I couldn’t see the fingers go by! It’s beautiful! His system of scales — I’ve got it all down now so you can see it. Starts out low E, one octave, E-major, “Brrrip,” F-major, “Brrrip,” F#, “Brrrip,” … OK.

JBY: That fast!?!

KO: Oh, yeah. If you can’t do it that fast, of course you start slow. You work up to it. Then we started scales in thirds. It took one hour to play scales in thirds — one hour! There was no daylight between the notes, no daylight. That was the essence of fine clarinet playing! Listen to any of his records.

JBY: Pure legato!

KO: Books and studies, and exercises I wrote, and am writing, all are encompassed in that. The basic premise that I work on is that you master clarinet. You play music. And then there was transposition. Everything I did for McLane never was just played, “as is.” The first transposition was “La”; next one was “Do”; and then loco. Sometimes if you were real nasty he’d shoot the E-flat at you. And never did he assign me anything that he didn’t do himself first. That’s how you pick up “smarts” at sight reading. …

JBY: You’ve had several distinguished musicians as students. One of them… [motioning to Richard Stoltzman]

KO: Let them talk … There it is right there.

RS: Well, I came to Kal for just what Kal was talking about. I didn’t know anything about the instrument. I found this book of his on reed making when I was in college … and I wrote Kal and asked him if I could come down to learn how to make reeds. So I went down, and by the end of that one day I was so shocked because, first of all, I realized that it wasn’t that I needed to know how to make reeds — it was that I needed to know about the whole, like what Kal was saying — the way, the path, how you get to the clarinet. And it was a terrible shock to be pretty much finishing up your so-called formal studies, getting your degrees and so forth, and thinking that you were just about to launch yourself as a musician. And then to have a person tell you that, in fact, you had really nothing. It wasn’t that you were hopeless, but you should just give up the idea that you played the clarinet and start all over again.

… There weren’t any tricks. He was very painfully truthful, you know. It was good for me. I was at the right age to do that. I don’t know what Kal saw in me — probably nothing — but I realize that even so he was willing to take on this huge responsibility. That’s why I’m not a teacher … I’ve had other wonderful teachers too, but the thing is that Kal was a kind of “life-teacher.” Sometimes your lesson was like getting a sandwich, and then coming back and copying some music, or just observing how cane was cut. It eventually got to the point where I finally lived in his house. He let me stay there and I would try to match his energy. I couldn’t do it. But he would go all night long sometimes on a project, like working on a mouthpiece. And he also was totally willing to toss out something that he’d spent huge amounts of time on when he decided it wasn’t good, it wasn’t right, or it was not going to be what he wanted. He was willing to immediately say, “Okay, that’s it.” I was shocked at this kind of dedication, and then I would start practicing, sort of what Kal was describing: getting up in the morning and playing, you know, and then he’d take me out and buy breakfast for me. Then we’d come back and I’d play a little bit in the other room while he was giving lessons to other people.

JBY: Did you ever listen to any of those lessons? What sort of impressions did you get from that?

RS: Yeah. Everybody came into his studio. I mean, what was really shocking were all the people who came from the most prestigious school down there a block (Juilliard), and many people who are now of course in major orchestras, but they never admitted — not only didn’t they ever admit they studied with him, they never admitted that they ever went down that street! Ha, ha, ha. And these were not just students, but players of the opera, the principal players of the ballet, principal players from other orchestras who came into town. They’d come in supposedly to just hang out or pay a call, but at the end of that time they would walk away with mouthpieces, barrels, reeds and stuff. I couldn’t believe Kal would do this for these people.

JBY: And knowledge!

RS: And of course they got the knowledge! So I ended up spending about three or more years with Kal. It was a stronger relationship than say, having your father or something. I finally moved to New York to live because I realized that I had to study with him. You know, he would call me up sometimes at two o’clock in the morning and he’d say, “Well, are you practicing?” I was asleep of course! Or he’d call up at the same hour, two or three in the morning, and he’d say something like, “We’ve got a problem.” And when he said “we,” he meant “I have a problem.” Then he’d say, “Put on your pants. Come over!” And I’d do it. It was like the middle of the night in Manhattan and there I’d go over to 17 West 67th, and there Kal would be working on some study or a project or some kind of thing and he’d say, “Get your horn out!” I used to think that some of the things Kal was telling me were dramatic for emphasis. He’d say, “I want to be able to call you up at three in the morning and [snaps fingers] you should be able to play the Mozart Concerto right there! Play now!” But then I realized later on in my career that actually sometimes I am playing the Mozart Concerto at three o’clock in the morning — if I’m in Japan, or some other place — what he said was exactly right. And everything that he said no matter how much I…

KO: He fought!

RS: I fought it, but he was right! I mean, he got me much more than just the clarinet. And I would say there are rare, rare teachers who care that much about the honesty of teaching, to basically give everything to a student. … I used to be frustrated and say once in a while that I’d want to pay Kal and he’d say, “Well, you know, I’m too expensive actually.” And it’s really true, not in financial terms; you just can’t pay somebody back when they give their life and stuff. You don’t pay it back — you just take it in and try to be true to it as much as possible. …

JBY: How was McLane to you? — personally and musically. How would you characterize his playing? Did he play for you in lessons?

KO: Oh, he never stopped! He would play for four hours. My lessons were four hours long — three and a half to four hours. Then we’d go, hop the train to WOR, Wallenstein Sinfonietta. He would play on Monday nights. He’d play with me all day and then we’d have dinner. We’d go to a Chinese joint. He loved Chinese food! And then we’d go to the radio station. I would sit there and then I’d catch the last train out and get back to the Army, West Point, about two a.m. McLane was one good guy. No one knew that man. I knew him well but I didn’t know him. He was a private man… …

JBY: So when you got to the lesson part what would you do?

KO: Whatever he had on his stand — that was my lesson. Whatever he was playing in the orchestra, a solo or studies, like Sarlit — that’s an old French book. It’s gone out of print, I think.

There’s one thing I did show him how to do — Rhapsody in Blue! He couldn’t do the glissando.

RS: But he’s probably not the guy who would practice glissandos very often.

KO: The hell he didn’t! He killed me. We did glissandos all day long. I went into the band and couldn’t play for two days after! My lips were [like rubber]. He was impeccable from the bottom up.

JBY: Didn’t he record that with the Philly Orchestra?

KO: Yessir! And he got offended because it was rumored that they were going to call Benny to do it. But he nailed that glissando! …

KO: There’s no substitute for hard work, and remember that time is your most precious commodity.

Clarinet Pedagogy Around the World

compiled by Rachel Yoder

Despite a desire to be a global organization, the International Clarinet Society in its early days was centered on the United States—as seen in the pedagogy articles reprinted here. In an effort to provide a wider view of pedagogy for this issue, ICA country chairs were recently asked to respond briefly to two questions:

- Who are/were the most important clarinet teachers in your country?

- Describe a concept or contribution from one of these teachers that impacted clarinet study in your country.

The responses collected here are in no way intended to be comprehensive, but they give a valuable glimpse into our varied and interconnected world of clarinet pedagogy.

Stephan Vermeersch, Belgium:

Jean Tastenoe, Pierre Bulté, Walter Boeykens, Eddy Vanoosthuyse, and Roeland Hendrikx. In an interview with Walter Boeykens, he said: “For me it’s just about music, the feeling, the timing. Not based on books on interpretation or analysis. Obviously, you play Debussy differently than Copland, Mozart, Weber, Brahms… I also think often in images. For example, Mozart does not need extensive interpretation but needs to be performed very sensitively and timed. I tell my students that music is like streaming water: no pound but a river. Music must be spontaneous. Melodies should flow. Concerning sound shaping, I use many vowels for the placement of tongue and the use of mouth and throat cavity so you can build a beautiful palette.”

Marie Picard, Canada, St. Lawrence:

It seems especially striking to me that clarinet playing and teaching in the province of Québec, Canada, has been greatly influenced by European masters. In fact, all of the clarinet professors of the previous generations named below have studied either in Paris, Rouen, London, or the Netherlands, in addition to Juilliard or Boston. Even the Conservatory Network of the province was a reproduction of its European sibling institution.

In Montreal, we have to salute the contribution of clarinetists like Rafael Masella and Emilio Iarcurto, who were both students of Joseph Moretti at one point; they were solo clarinetists of the Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal and taught at McGill University and the Conservatoire de Musique de Montréal. Another important name is Jean Laurendeau, soloist and chamber player, who, in addition to teaching clarinet for a long time at the Conservatoire de Musique de Montréal, was also a sought-after player of the ondes Martenot, after studying with Jeanne Loriod and Maurice Martenot himself.

In Québec, I must mention Pete Coomans, who came from the Netherlands, and Wilfrand Guillemette, who were both members of the Orchestre Symphonique de Québec and taught at the Conservatoire de Musique de Québec. The last but not least of the clarinet teachers on my list is Armand Ferland, whose musical career as a conductor in the Canadian Armed Forces and as a clarinet professor and music educator at Laval University was remarkable. All those people have given birth to several generations of great pedagogues and clarinetists, many of them orchestra players, in recent decades.

James Kalyn, Canada:

Robert Riseling (University of Western Ontario) teaches an inseparable connection between the head and the heart in playing the clarinet (or any instrument). The truly effective player understands the music: the theory above all, but also the history and people. They also understand the instrument, and the body. They have thought through phrasing, style, and all manner of musical details with great care. All of this is put into passionate service of the music. Riseling embodies these beliefs in his playing, and through his playing and teaching has inspired generations of clarinetists to pursue his high ideals.

Christine Carter, Canada:

I would like to recognize Robert Riseling (Western University) for his tireless dedication to students and teaching. When I was a student at Western, he voluntarily taught everyone two lessons a week—one for repertoire and one for technique—knowing that we had a long way to go if we wanted to end up as professionals in the field. He was also instrumental in the commissioning of new Canadian works. There were dozens and dozens of new pieces written for him, thanks to his commitment to championing contemporary Canadian music. Many of Bob’s students have gone on to professional careers across North America and he made an impact across the world with his extended teaching trips, including in Hungary and China.

Marie Picard has been one of the most significant Canadian clarinet teachers in recent decades. As the clarinet professor at the Conservatoire de musique de Québec for almost 30 years, she influenced generations of clarinetists with her immense knowledge, leadership, and unfailing kindness. Marie is someone who has always championed others and so I am not surprised that she has listed many other teachers as being influential in the Canadian scene. But countless Canadian clarinetists would cite Marie as their most important teacher. For decades she also taught at Domaine Forget in Québec. Many students from all over the world attended Domaine Forget for the big international master class guest artists, however it was often in private lessons with Marie Picard that the most work was accomplished! She is an exemplary mentor and has had an incredible impact on so many of us across the country and also internationally. The fact that the clarinet section of the Orchestre Symphonique de Québec consists entirely of her students is a testament to her incredible pedagogy.

Luis Rossi, Chile:

Julio Toro, principal clarinet at the Chilean National Symphony from 1940 to 1960, was the main clarinet instructor during those years. Starting in 1980, I developed my own large clarinet studio at the Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile. These days, most Chilean orchestras have clarinetists that have been trained at the Universidad de Chile by Ruben Gonzalez, one of my former students. And other former students like Kathya Galleguillos and David Medina (principal clarinet at the Chile National Symphony) are now developing new and successful studios at the Universidad Mayor and the Pontificia Universidad Catolica.

Jean-Marie Paul, France:

The French school, based mainly on Paris Conservatory teaching, had many important professors from F. Berr and X. Lefèvre on; I chose two names belonging to this founding school and two more recent names: Hyacinthe Klosé (1808-1880), Cyrille Rose (1830-1902), Jacques Lancelot (1920-2009), and Guy Deplus (1924-2020).

For more info, you can refer to my papers in the French Wikipedia or in The Clarinet: Klosé (2006, vol. 33/3), Rose (2022, 49/3), Lancelot (2006, 34/1). For Deplus there are several interesting papers (1980, 7/3; 1998, 25/4; 1999, 26/4; 2010, 37/2; 2011, 38/3).

Why such a choice? In 1839, Klosé published the most popular method of all-time and exhibited the Boehm clarinet he designed with Louis A. Buffet. He taught at the Paris Conservatory for 30 years, training many students including his three successors (Leroy, Rose, and Turban). He wrote the solos de concours during his tenure from 1839 to 1868, and many other works. Rose is famous for publishing many studies. He brought more musical phrasing and also had famous students to perpetuate the tradition (his successor Mimart; H. Paradis, H. and A. Selmer, P. Jeanjean, L. Cahuzac, H. Lefebvre; M. Gomez from Spain, etc.). Lancelot taught in Rouen and Lyon, and abroad (notably in Japan). He also wrote famous studies in his huge collection of scores at Billaudot and EMT. Deplus brought his knowledge of contemporary music to the Conservatoire (as a founding member of the Boulez ensemble). Of course each of these personalities brought their experience of orchestral music (Paris Opera, Garde Republicaine, etc.), of premieres with composers, playing of concertos and chamber music. All of them were also artistic advisors to a famous French maker. Lancelot and Deplus also could share their artistry by recording many masterpieces.

Bence Szepesi and Istvan Varga, Hungary:

Those who have done the most for the Hungarian clarinet society include György Balassa (1913-1983), Ferenc Meizl (1924-2019), Béla Kovács (1937-2021), László Horváth (1945-2022), and Kraszna László (1947-2020). György Balassa was principal clarinet of the Hungarian State Philharmonic Orchestra, a founding member of the Budapest Wind Ensemble, and professor at the Ferenc Liszt Academy of Music. He performed the Hungarian premiere of Béla Bartók’s Contrasts and many other pieces. He published pedagogical works including Clarinet School (1950), Methodology of Clarinet Playing (1973), and Studies for Clarinet (1974). Ferenc Meizl was principal clarinetist of the Hungarian State Opera House Orchestra, member of the Budapest Wind Ensemble, professor at the Teacher Training Institute in Budapest, then head of department for 25 years. He made numerous transcriptions for wind quintet, and in 2000 his study Didactics of Teaching Chamber Music was published. Béla Kovács was principal clarinet of the Hungarian State Opera House and the Philharmonic Society, and professor at the Academy of Music in Budapest and the Universitat für Music in Graz, Austria. As a soloist he gave many concerts abroad and Hungary, and he made many radio and CD recordings. His publications include Everyday Scale Exercises (1979), Learning to Play the Clarinet I and II (1983, 1986), and many of his own works including the Hommages, which are played all over the world. László Horváth was principal clarinetist of the Hungarian State Philharmonic Orchestra, founding member of the Filharmónia Wind Quintet, and professor at the Béla Bartók Secondary School of Music in Budapest. He was director of the Lajtha László International Music Festival in Kőszeg for 15 years, and premiered the Clarinet Concerto by Sándor Veress along with several contemporary Hungarian works. László Kraszna was a member of the Hungarian State Philharmonic Orchestra and a founding member of the Budapest Clarinet Ensemble, and taught at the University of Szeged, the Béla Bartók Secondary School of Music, and the Snétberger Music Talent Centre. His publications include three volumes of his Hangsortanulmányok, and Studies on Clarinet and Saxophone Playing.

Christian Stene, Norway:

Oslo: Richard Kjelstrup (1917-1997), Hans Christian Bræin (b. 1948), Björn Nyman (b. 1977)

Bergen: Lars Kristian Holm Brynildsen (1954-2005), Christian Stene (b. 1980)

It is natural to single out Hans Christian Bræin, who was professor at the Norwegian Academy of Music from 1990-2013. He had a great impact on the education of clarinet players in Norway and had an international focus attracting many foreign students to Oslo. His sonorous concept had a wealth of timbres and he was uncompromising when it came to beauty of sound.

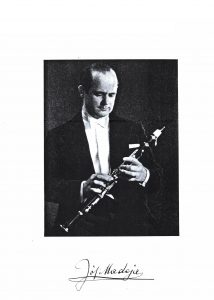

Barbara Borowicz and Paweł Kroczek, Poland:

Józef Madeja (1892-1968) developed schools of playing the clarinet in Poland and composed new etudes and pieces for clarinet. Ludwik Kurkiewicz (1906-1998) began to introduce the French clarinet in Poland.

Paweł Roczek (who lived in the 20th century) contributed to the development of the clarinet in Silesia, part of Poland.

Madeja—Polish clarinetist, teacher, composer, and organizer of musical life—received his musical education in Zabrze, Weimar, and Berlin. In 1920, Madeja began teaching at the newly established Academy of Music in Poznań. In addition, he also lectured at secondary schools in Poznań, the Bydgoszcz Conservatory and the State Higher School of Music in Wrocław. Graduates of Prof. Madeja were valued musicians of the best orchestras in the country (Warsaw, Poznań, Wrocław, Bydgoszcz, Gdańsk) and university lecturers (Poznań, Warsaw, Łódź, Wrocław, Bydgoszcz). Józef Madeja, aware of the lack of any specialized literature in Polish, developed schools of playing the clarinet, bassoon, and oboe. With his students in mind, he composed several dozen works. Madeja’s creative output is dominated by clarinet works, but he is also the author of individual pieces for flute, oboe, bassoon, and trumpet.

António Saiote, Portugal:

It is difficult to choose just five because so many of my former students continue doing a great job and achieving great results, making the Portuguese clarinet school a world reference: Nuno Pinto, dedicated to contemporary music and extending new techniques and inspiring composers as new music professor at ESMAE; José Ricardo Freitas, a specialist teaching beginners and developing clarinetists until 17 years old when they enter university; Luis Gomes, dedicated to bass clarinet as performer and pedagogue, inspiring students and composers for the instrument; João Pedro Santos, like José Ricardo Freitas, an expert on young people and also extending the clarinet to world music as performer; and Iva Barbosa, a very good pedagogue, soloist in the Gulbenkian orchestra and a very good communicator of music education.

I would also like to add Vitor Pereira, soloist of the equivalent to the French IRCAM and a very good teacher, organizer of the Ibero-American clarinet academy; Vitor Matos from Braga University who taught Sérgio Pires, soloist of LSO; Nuno Silva, of the Metropolitan Orchestra and Academy; and Carlos Alves, from Castelo Branco University.

Cosmin Harsian, Romania:

Here are a few names of important clarinet pedagogues that made a big contribution to advance the clarinet study in Romania during the last 70 years: Dumitru Ungureanu (professor at the Ciprian Porumbescu Conservatory in Bucharest), Ion Cudalbu (professor at the Ciprian Porumbescu Conservatory in Bucharest), Ioan Goilă (professor at the Gheorghe Dima Music Academy in Cluj), Rodica Sas (professor at the West University of Timișoara), and Dumitru Sâpcu (professor at the National University of Arts George Enescu Iași).

One of the most important clarinet professors in Romania during the mid-20th century was Dumitru Ungureanu. He taught at the Bucharest Conservatory between 1938 and 1970 and is the one that introduced the Böehm clarinet system in Romania, in 1950. Between 1960 and 1970 Ungureanu wrote the first Romanian method for clarinet, Metoda de Clarinet, in two volumes for beginners and advanced students. This method was adopted as one of the main teaching tools in all schools within the country. As his teaching style accentuated the multilateral development of the student as an interpreter-creator, many of his disciples won important awards in big international competitions.

Andrija Blagojević, Serbia:

Those who are the best known to today’s clarinetists include (in chronological order): Milenko “Mima” Stefanović, Ante Grgin, Nikola Srdić, and Ognjen Popović, and perhaps myself, according to the opinion of my colleagues. Ognjen Popović (b. 1977 in Pančevo, Serbia) studied in Serbia and in Germany, in the class of Professor Ulf Rodenhäuser. He has performed throughout the world as a soloist and chamber musician and was a prizewinner in numerous competitions. He was appointed principal clarinetist of the Belgrade Philharmonic Orchestra in 2002. He is a founding member of the Balkan Chamber Academy and the artistic director of the Classic Fest international chamber music festival in Pančevo. Since 2010, he has been teaching at the University of Arts in Belgrade Faculty of Music, where he is currently an associate professor of clarinet. Popović has shared his knowledge and experience with numerous students at the bachelor’s, master’s, specialist, and doctoral level.

Stefan Harg, Sweden:

After B.H. Crusell, who attracted players to come here and study with him, the teaching tradition was passed to Johan Gustav Kjellberg (1846-1904), who taught all the woodwind instruments at the Royal College of Music Stockholm. He had a big influence on later teachers. Next was Emil Hessler (1873-1953); he taught many foremost clarinetists at the Royal College of Music Stockholm from 1904-1940. Nils Otteryd (1906-1981), student of Aage Oxenvaad, taught at the Royal College of Music Stockholm from 1938-1973. These professors divided their time between playing in the Royal Court Orchestra Stockholm and the Svea Lifvgarde Military Band, and teaching at the Royal College of Music Stockholm.

The other teacher of importance who many studied with, and who also designed and rebuilt instruments, was Ludwig Warschewski (1880-1950), teacher at the Royal College of Music Stockholm from 1935 to 1950 and principal clarinet in the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Stockholm, former solo clarinet of the Berlin Philharmonic. His student Thore Janson (1914-2002), principal clarinet of the Royal Philharmonic Stockholm, took over his legacy and taught from 1960-1986. After this the main professor at the RCM was Sölve Kingstedt (1932-2021), principal clarinet of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Stockholm.

The importance of playing in a mix of German/French style is evident in Sweden, in players like Sölve Kingstedt, Sten Pettersson, and Kjell-Inge Stevensson. All of them started to play in a more individual way mixing the two traditions. They all used much more free-blowing material. The emphasis was a more bel canto style of playing. We must say that the influence now here in Sweden is a very big mix of individual playing along with the ideas of US players like Yehuda Gilad, the Belgian Walter Boeykens, and the French Guy Deplus.

Kinan Azmeh, Syria:

Shukry Shawky was a Syrian clarinetist, one of the first clarinet players/teachers in the country. Also, Nikolay Viovanof, Anatoly Moratof (both Russians); these were my main clarinet teachers back in Damascus at the Arab Conservatory and at the Damascus Higher Institute of Music. The common thread that united all these teachers is that they were teaching an instrument that is largely foreign to the culture. The clarinet-playing resources were very limited. I still have scores/parts from the repertoire that these teachers transcribed to us students by hand because obtaining original scores was simply not possible. These wonderful teachers instilled in their students the philosophy that passion, dedication, and hard work combined can overcome the obstacles imposed by the lack of access to suitable gear (mouthpieces, reeds, instruments). Moratof (with whom I studied for my bachelor degree) believed that the sound you produce on the instrument has nothing to do with what you hold in your hand and the kind of reed you use, but rather simply with what you hear in your heart, and that if you can imagine the clarinet sound you like you can actually produce it, and I like that philosophy very much.

Danre Strydom, South Africa:

Heinrich Armer (retired), University of the Free State (teacher in Free State); Mario Trinchero (passed away), principal clarinet SAUK (teacher in Gauteng), Jimmy Reinders (retired), University of Stellenbosch (teacher in Western Cape).

Quang Tran, country chair for Vietnam:

One of the most important clarinet teachers in Vietnam is Dr. Vu Dinh Thach (V˜u Đình Thạch). He taught at the Vietnam National Academy of Music for decades. Many of his students are now the most important clarinetists and teachers of the nation and elsewhere. A graduate from the Moscow Conservatory (Tchaikovsky Conservatory), his insights and his passion for the clarinet are extraordinary. His pedagogical methods are excellent in many aspects, yet the most important is that Dr. Vu Dinh Thach knows how to nurture and foster students to work hard and develop their own musicality to be their best.

Comments are closed.