Originally published in The Clarinet 48/3 (June 2021). Printed copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

Pedagogy Corner

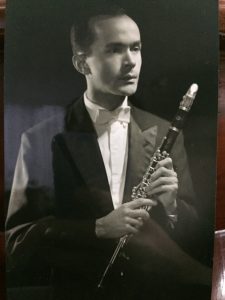

Listen Closely: The Legacy of Roberto Mantilla Alvarez

by Phillip O. Paglialonga

Read the Spanish Version of this article here: https://clarinet.org/pedagogy-corner-escucha-con-atencion-el-legado-de-roberto-mantilla-alvarez/

Music is a uniquely aural experience. You cannot touch music, nor can you taste it. We try our best to represent music visually, but no matter our efforts we can never convey music fully without listening to musical sounds.

In our quest to become better musicians and clarinetists, too often we fail to fully engage with music within its own sonic world. Of course we can learn a great deal about music by engaging with it in other ways, but I suggest that we should put more energy into simply listening to exceptional playing.

Today’s modern world affords us more resources than any one person could possibly fully explore. As a result, I think sometimes we forget how much we can learn simply from listening.

A generation ago, Roberto Mantilla Alvarez (1932-2017) achieved a high level of musicianship by relying almost entirely on his ear to guide him. He was largely self-taught, and was able to achieve a remarkable level of performance simply by listening intently to the playing of those around him. His story is an important reminder to each of us of how much we can discover simply by listening more closely.

Below you will find excerpts from an interview I did with my dear friend, Javier Astrúbal Vinasco about his former teacher. Vinasco has established himself as one of South America’s most important clarinet pedagogues and currently lives in Medellín, Colombia. He has recorded extensively, including more than 100 works by Latin American composers, and was nominated for a Latin Grammy Award.

As you read the interview with Vinasco you will see how a humble, yet talented, musician used the power of intense listening and hard work to become a world-class clarinetist.

Roberto Mantilla

Phillip O. Paglialonga: Some people living outside of Colombia may not know much about Roberto Mantilla, could you tell us a little bit about who he was?

Javier Vinasco: In my opinion, he is a real unknown gem to many outside of my country. Roberto Mantilla was a great Colombian clarinet player and teacher. I studied with him for more than two years. He taught at the National University in Bogotá for many years, and passed away in 2017 at the age of 85. He was the principal clarinetist at the National Symphony Orchestra of Colombia, since he was 21. After the Second World War, a couple of good European clarinetists worked in Bogotá: Luigi Neroni who later was principal at the Rome Opera Orchestra and Alfred Rose, who years later became principal at the Wiener Symphoniker and teacher at Graz Musikhochschule. Rose was appointed to the orchestra in Bogotá as second clarinet and Mantilla never took lessons from him (because he was his principal), but he listened carefully to his way of playing and learned a lot. Mantilla never had a formal clarinet teacher, he was totally self-taught, but Rose was undoubtedly a huge influence on him. In 1962, Mantilla, who never traveled abroad, went to the 11th ARD Munich Competition. He played everything on an old Selmer Bb instrument with a low Eb, using a very light and subtle vibrato. On the jury was Jack Brymer and in the competition with him, Hans Deinzer and Karl Leister, among others. Mantilla advanced to the final round: the first prize was vacant, the second one was for Leister and the third for Mantilla. After the competition, he was invited to play as soloist with the U.S. Air Force Symphony Orchestra in Washington D.C. and had job offers in Germany and the United States, but decided to return to Colombia where he was active as a clarinetist until he retired at age 65.

POP: Could you talk a bit about his playing style? Do you think his approach has had a lasting influence on the way clarinetists in Colombia play today?

JV: Unfortunately, when I studied with Professor Mantilla he had been retired from playing for three years, so I never was able to hear a live performance. Though he played short examples in my lessons, I have to say, sadly, that I cannot comment on his performances firsthand. Nevertheless, I can speak about the musical values he taught me. In regard to his influence in Colombia, I know that he was very respected in his time; however, I find that now, more than two decades after he retired, students and even professional clarinetists know little or nothing about him. Thinking about that, I find three possible reasons this is the case: 1) Once he retired from the orchestra he stopped playing and barely taught; 2) He did not have an international career, which is very important to earning respect in Colombia; and 3) It is not a common practice in Colombia to preserve the memory of the past or a legacy of a prominent person like is so commonly done in other places.

Roberto Mantilla debut at 12 years old

POP: What were your lessons with Mantilla like? What sorts of things did you play for him? Did he have any specific exercises or methods that he used?

JV: Professor Mantilla always stressed the importance of listening carefully and practicing a lot. This was the way in which he learned. According to him, the sound was the most important aspect for a clarinet player. He was a perfectionist, very aware of rhythm and quite particular about the articulation. He also developed a lot of alternative fingerings for each orchestral solo or difficult passage in a concerto or sonata. At the lessons, he used different methods and etudes, such as those by Rudolf Jettel, Paul Jeanjean and Alfred Uhl. His preferred exercises were doing a group of a few notes with different rhythms, repeating them like a cycle or playing very slowly in order to develop the sound of each note,

one by one.

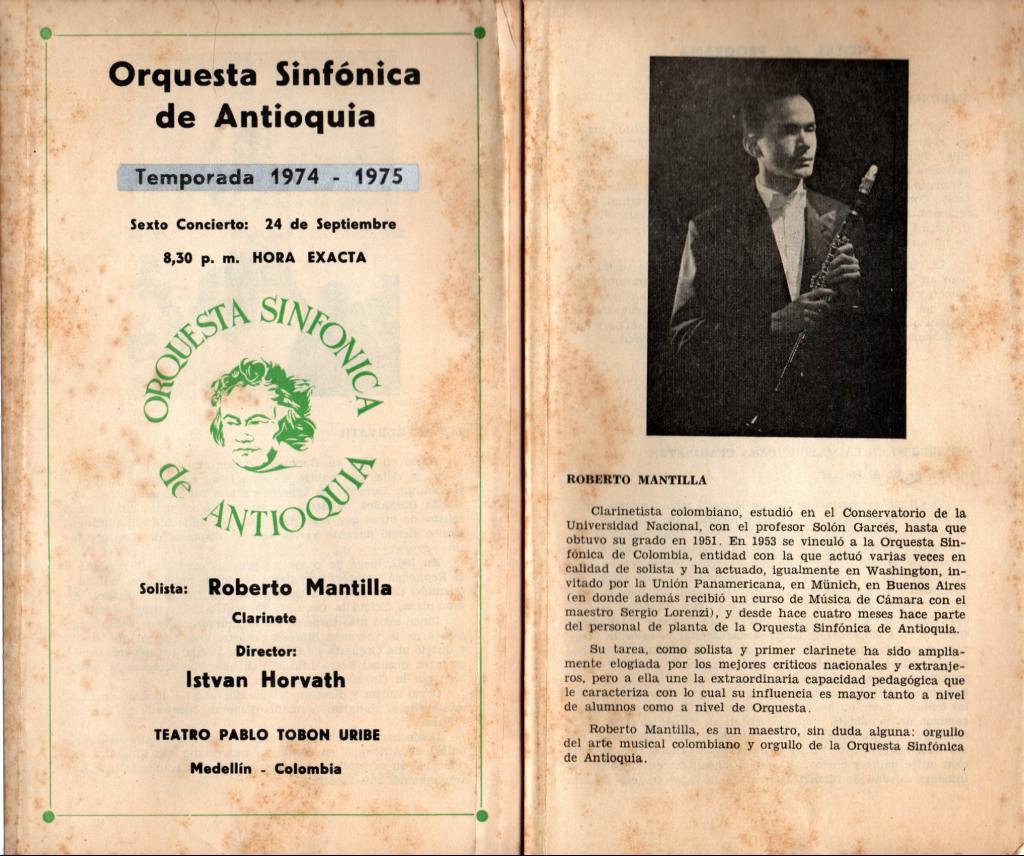

Mantilla in Medellín

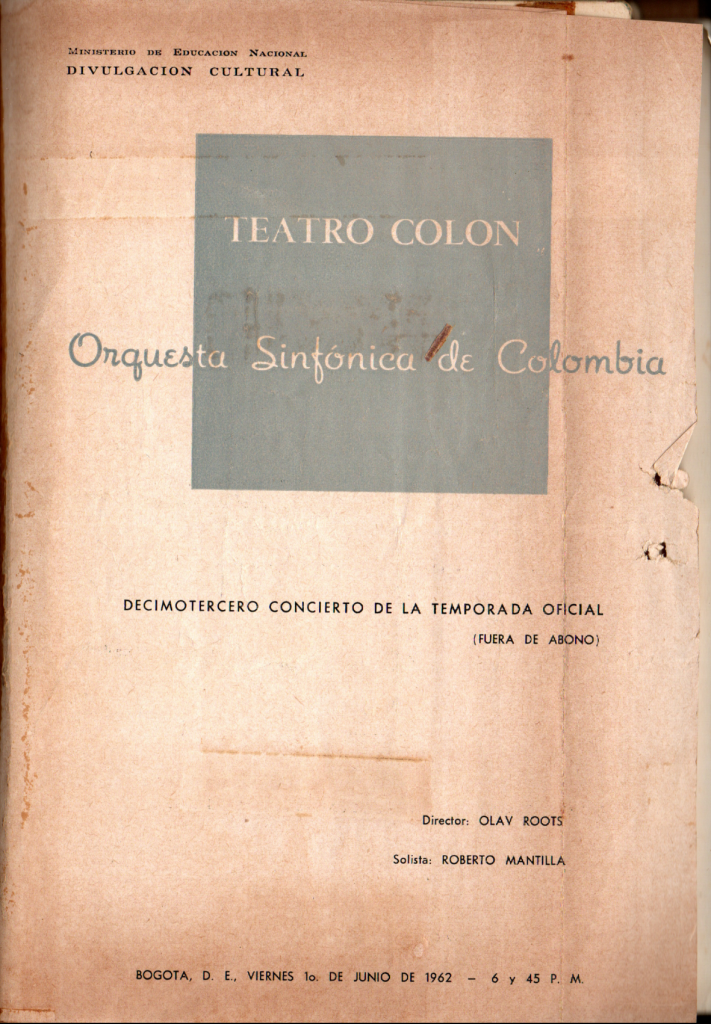

Concert program from June 1962 in which Mantilla was soloist with the Orquesta Sinfónica de Colombia

Antonio Alvarez, Luigi Neroni and Roberto Mantilla

POP: Since many of us outside of Colombia are largely unfamiliar with his playing, do you know of any recordings of his playing that are still available?

JV: I only have one recording of Mantilla in which he plays the Mozart Clarinet Concerto. Once he said to me that in his time recordings in Colombia were scarce and that he was always disappointed with their quality. He told me that in the National Radio archive there are some recordings of his live performances, but I don’t know how well preserved these recordings would be.

POP: When you encounter a serious clarinetist in Colombia today that knows only about the history of him doing so well in the Munich competition, what else do you tell them about?

JV: This is a very important question. The legacy of Roberto Mantilla, for many people in Colombia, has changed with time. We are so removed from his story that we forget that he was a real person and that his humanity was a big part of his musicianship. I remember that once, in a lesson at his house, he told me, “Excuse me, I have to go to a bank for half an hour, please feel free to play and practice. I will be back soon.” Without my knowledge, he went to the room next door and listened to me practice. Then, he apologized and gave to me the best advice I ever had about how to optimize my practice. For me, the legacy of Mantilla is that he taught with the assumption that everything is possible if you work hard. It does not matter where you live, or if you have the latest clarinet, mouthpiece or accessories; what matters is your discipline, determination, love for music, and professional ethics.

Colombia in the 1950s and ’60s was characterized by the lack of everything to make music appropriately. Lack of good teachers, instruments, reeds, mouthpieces, ligatures, books, recordings, as well as possibilities of traveling abroad and getting contact with the mainstream of classical music. I think that, in this context, Mantilla was like a flower in a desert. In these difficult conditions, he was extraordinary. Only a person with a very high professional ethics and love for music and clarinet can get over his reality, and inspire others to make their wildest dreams come alive.

Roberto Mantilla and Javier Vinasco

* * * * *

In preparing this article I spent a lot of time trying to discover some hidden technique or approach that I could pass along, instead of accepting that Mantilla lived in a time and place very different from ours. He did not have the abundance of equipment to try, or even the endless supply of reeds we now take for granted. And yet, he found ways to create the sound he wanted.

I find Mantilla’s story to be incredibly inspirational, and an important reminder that we can each find so much more musically simply by taking the time to slow down and really listen closely to exceptional playing every chance we get.

* * * * *

Author’s Note: Thank you to Jairo Peña, Hernán Darío Gutiérrez, and Carlos Saldaña for their help providing information and materials about Roberto Mantilla.

About the Writer

Phillip O. Paglialonga is associate professor of clarinet at the University of North Texas and pedagogy coordinator for the International Clarinet Association. More information about him is available online at www.SqueakBig.com.

Comments are closed.