Part 1 Originally published in The Clarinet 46/3 (June 2019); Part 2 Originally published in The Clarinet 47/3 (June 2020). Printed copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

Manuel Gómez and the Gomez-Boehm Clarinet: The Legacy of a Legendary Clarinetist

by Pedro Rubio

Part I – The Life of Manuel Gómez

A definite step in English clarinet-playing is marked by the arrival in London of Manuel Gomez in the late 1880s. […] The influence of Gomez on the younger school of players was great. It may be said that he introduced the Boehm system to England. And further, he provided a stimulus.

In spite of the efforts of Lazarus and Clinton, interest in the clarinet as a solo instrument had been declining. Gomez did much to restore it by inducing musicians to compose for it.

– F. Geoffrey Rendall, The Clarinet1

Manuel Gómez had a brilliant career during the last decades of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th: Gómez was a laureate of the Madrid and Paris conservatories, principal clarinet of some of the best orchestras of the time – among them the Paris Opera, the Covent Garden Opera Orchestra and the Queen’s Hall Orchestra – and founding member of the London Symphony Orchestra. However, his path in the clarinet world went beyond his role as orchestral musician. Aside from the music written for him and his influence on younger clarinetists, he also attracted the attention of the British maker of wind instruments Boosey & Co. During the 1880s and 1890s, this maker introduced various improvements to clarinets and several new designs, two of them following the indications of prominent artists. In 1883, the Clinton-system clarinet appeared, designed in collaboration with the British clarinetist George Clinton (1850-1913), and in 1899, a new Boehm model was produced following the specifications of the Spaniard Manuel Gómez (1859-1922).

Part 1 of this article will explore the highlights of Gómez’s biography, and Part 2 will describe the characteristics of the clarinet developed for him by Boosey & Co. The excellent book Clarinet Virtuosi of the Past by Pamela Weston, published in 1971, is still an essential reference for any matter related to the biography of Manuel and his equally famous brother Francisco (1866-1938).2 Coupled with this, the documents and information provided by the Gómez family, especially by the Canadian clarinetist Harold Manuel Gomez,3 Manuel Gómez’s grandson, have been of special importance.

The extraordinary story of the Gómez brothers

In her book Pamela Weston tells how two brothers, under extremely adverse circumstances, came to be protagonists in the musical scene of England at the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries. With a certain romantic tone to the story, Weston relates the events that led Manuel first to Madrid, and later, the two brothers to Paris and London.4

Seville

It was the mid-19th century. A humble family lived not far from the cathedral and its famous bell tower, La Giralda. The father earned his livelihood in the manufacture of harnesses contracted by the municipality of the city. They had three children: Trinidad, Manuel and Francisco. Shortly after Francisco was born the family situation changed dramatically, and the children, with their mother Isabel, coped with an uncertain future. To make matters worse, the mother began to lose her sight. Faced with this situation, Trinidad was to remain in her care, Francisco went to live with his maternal grandmother and Manuel was sent to an orphanage in Seville. Around 1850 a music band was formed in the heart of the orphanage, and Manuel received clarinet lessons from the director of the band, Antonio Palatín. The young clarinetist progressed rapidly in his musical studies. When Manuel reached the stipulated age to leave the institution, he needed to look for a way to make a living.

Madrid

With a determination that would characterize him throughout his life, Manuel decided to travel to Madrid, where he studied at the conservatory while playing in numerous performances of concerts and zarzuelas (Spanish operettas) in the capital of Spain. His teacher at the conservatory was Enrique Fischer y Pagés (1821-1889), and he studied there between October 1879 and June 1881. That year he earned the First Prize in clarinet.5 Francisco, meanwhile, followed the example of his older brother, studying the clarinet with great dedication, also under the teaching of Palatín. The Gómez brothers’ fame began to spread throughout Seville. Through the local government, a popular subscription was organized to send them to the Paris Conservatory. The initiative was a great success and the two brothers prepared to begin a new stage in the French capital.

Figure 1. Sir Henry Wood and the soloists of the Promenade Concerts. Flute: Albert Fransella, oboe: Desiré Lalande, French horn: Emil Borsdorf, clarinet: Manuel Gómez and bassoon: Edwin James. William Whiteley Ltd, c. 1899. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Paris

In September 1882 the Gómez brothers were in Paris. As they did not speak French and had no money for language classes, they learned it while working in the cafés of the city. They took the tests for access to the conservatory and entered as scholarship students in the clarinet class of Cyrille Rose (1830-1902). At that time, they switched their outdated 13-key clarinets for a pair of Boehm-system clarinets. During the next four years, the Gómez brothers were dedicated to perfecting their technique and both finished their studies as award-winning students. For the laureates of the Paris Conservatory the next step, if they were lucky, was to enter the opera orchestra. According to Pamela Weston, Manuel obtained this goal and managed

to enter as first clarinet with the Paris Opera Orchestra.

London

In May of 1886 Manuel Gómez crossed the English Channel, headed to London as a member of an opera company. In November he was joined by Francisco, who was hired by a French orchestra, to participate in the opening of the Olympia Theater of London.6 Like today, in those days the British capital was one of the major centers for music in the world; it was an essential stop for the best artists of the time. The Gómez brothers made their residence there, and in a short time they earned such a reputation that they had offers from all over the country. On June 24, 1887, only a year after his arrival, Manuel appeared as a soloist in an extraordinary concert event held at Covent Garden in the presence of the Queen Victoria to celebrate the 50th anniversary of her accession to the throne.

In 1892, Manuel and Francisco met a young conductor named Henry Wood (1869-1944) and, from that moment on, most of their professional career was under his baton. This is also the year in which the two brothers joined the Covent Garden Opera Orchestra. In 1894, the Queen’s Hall Orchestra was founded and both brothers became part of it from the beginning: Manuel as first clarinet and Francisco as second. Francisco also played the parts of bass clarinet and basset horn, coming to be considered the best bass clarinet player in England.

The Proms (Promenade Concerts)

The Promenade Concerts were created by Henry Wood so that anyone could attend a classical music concert in London regardless of whether they could afford tickets. At first the atmosphere was informal; you could eat and drink during the concert, being respectful of the interpretation of the orchestra. The name refers to the part of the audience located in the area without seats, where the Promming tickets (standing room only) were the cheapest. The spectators used to walk through some parts of the huge auditorium while listening to the concerts.

On August 10, 1895, the first Promenade Concert in history took place. These concerts were performed during the first years by the Queen’s Hall Orchestra. As members of that orchestra, the Gómez brothers participated in this historical event. With the popular and multitudinous character that has characterized the “Proms” until today, on that occasion they interpreted 25 pieces by authors such as Wagner, Leoncavallo, Chabrier, Chopin, Saint-Saëns, Liszt, Bizet, Rossini, Schubert and Haydn.7

Figure 2. Promenade Concert program,

September 24, 1896. Gómez family archive,

Toronto, Canada.

The London Symphony Orchestra

Between the manager and several members of the Queen’s Hall Orchestra there emerged differences on how to manage the orchestra. These tensions led to a split and the birth of a new formation. Again, Pamela Weston gives us the details of that historic moment: in the autumn of 1903, during a train trip from Manchester to London, Manuel Gómez and three of his colleagues gave form to a plan for the creation of a new orchestra. The fundamental idea was that from the beginning this orchestra should be self-managed, and the musicians also reserved the ability to hire or fire the director. The London Symphony Orchestra was born. Many of the members of the Queen’s Hall Orchestra went to the new orchestra. Manuel became its first clarinet soloist; Francisco, instead, preferred to remain in the Queen’s Hall. The London Symphony gave its first concert on June 9, 1904, with Hans Richter (1843-1916) conducting. The idea of self-management continues to this day in an orchestra considered as one of the most important musical institutions in the world.

In the spring of 1912, the London Symphony Orchestra made a successful tour of the United States and Canada under the baton of Arthur Nikisch (1855-1922). This was the first time a European orchestra visited America. The tour was very intense, with 28 concerts in 21 days and in 23 different cities. During the trip, the Boston Symphony Orchestra tried to convince Manuel Gómez to stay in the city, offering him the position of first clarinet. However, Manuel kindly rejected the offer, taking the trip back to London in mid-April 1912.

Figure 3. The London Symphony Orchestra. First known photo, July 1904. Manuel Gómez pointed out with an arrow. © LSO Archive.

The first recordings

Thanks to his prestige and notoriety, Manuel Gómez was invited in 1904 to make a recording for the emerging phonography industry. It was one of the first recordings in history made by a clarinetist. Gómez interpreted variations of the theme “Caro nome” from the opera Rigoletto by Verdi.8 The Gómez family has described Manuel’s comments about the recording sessions. He explained that, according to the technicians, the two most complicated instruments to record were the snare drum and the clarinet. The first one sounded like a forest was burning and the second as if it were a mixture of squeaks and howls. For those years no retakes could be made, and Manuel had to play only once and from start to finish.9

The last years

Manuel Gómez retired in 1915, although he remained active participating in concerts until 1921. His health deteriorated rapidly because of cancer and he passed away at age 62 in London on January 8, 1922. Francisco, after the death of his brother, abandoned London and settled in the coastal town of Llandudno, in North Wales. There, after a few years, he was offered the position of first clarinet in the Orchestra of the Belfast Radio. In 1936 he retired from the orchestra although he continued collaborating in the concerts of the philharmonic society of the city. Two years later, on January 5, 1938, Francisco Gómez passed away in Belfast.

Figure 4. Francisco Gómez sitting with his

clarinet, c. 1895. Wardale family archive, U.K.

Thanks to its intense musical activity, England gave to the Gómez brothers the opportunity to develop their talent and be protagonists of a period when symphony orchestras were transformed into what we know today. But they also shared the fate of the country that hosted them during its most difficult times, and, like so many others, paid a heavy price for it. During World War I, the sons of Manuel and Francisco participated in the war fighting for England. One son of Francisco, Philip, died during the Second Battle of Ypres (Belgium) on May 10, 1915. Henry, son of Manuel and father of clarinetist Harold Gomez, had more luck. He participated in the Battle of Gallipoli, one of the most hard and bloody throughout the war, surviving a severe leg wound. Years later, during World War II, a flying bomb fell on the Gómez house in London, killing Manuel’s wife, Adela, and her oldest daughter Adela Isabel on the spot. They found the younger daughter Marice Elena badly wounded; her mother had protected her with her body upon hearing the arrival of the bomb, and although she survived, she never fully recovered.10

Manuel Gómez’s way of playing

Before moving to the description of the Gomez-Boehm clarinet, it is worth mentioning a significant feature of Manuel’s way of playing. Since his arrival in England, Manuel Gómez was well-known not only for the quality of his sound and his exceptional mastery of the instrument, but also for playing on his clarinet in B-flat, at first sight and without any error, all the parts for clarinet in C, B-flat and A. In Rendall’s words, “His execution was quite exceptional, and the wonder it aroused was increased when it was noticed that he played everything upon one clarinet.”11 Weston notes, “He never used anything but a B-flat clarinet himself. To the surprise of English audiences he transposed all other parts on to the one instrument.”12 Gómez was an illustrious representative of a practice shared especially among orchestral clarinetists from countries of southern Europe until well into the second half of the 20th century.13

Figure 5. The Manuel Gómez family in 1908. Standing: Henry (Harold’s

father), Manuel and Manuel son. Sitting: Margot, Adela (Manuel’s wife) with

Marice Elena in her arms, Adela daughter and Arthur. Gómez family archive,

Toronto, Canada.

Figure 6. The Francisco Gómez family in 1913. Standing: Philip, Frank and

Paul. Sitting: Francisco, Romaria, Marie Ann (Francisco’s wife), and Maud in front. Wardale family archive, U.K.

Manuel Gómez almost certainly acquired his transposition practice in Spain. Around 1870, Antonio Romero, the most influential Spanish clarinetist of the 19th century, added to his clarinet system the low E-flat key with the main objective of transposition. So, it is very likely that this tradition among the Spanish clarinetists was carried out from those years. There are testimonies that clarinetists used this habit in orchestras at least between the 1920s and 1970s.14 In the mid-20th century it was general practice as we can verify in these words written c.1950 by the clarinetist Julián Menéndez (1895-1975) for the prologue of his 32 estudios de perfeccionamiento:

I recommend these studies as good preparation to get fluency and practice in the most varied keys, especially considering that the usual way in Spain is to play with a single instrument all parts written for clarinets in C, B-flat and A.15

To carry out the transposition, the clarinetist needs an instrument which can play a semitone lower to low E-flat and several additional keys. Among other attempts, during the second half of the 19th century a new clarinet model was developed having the standard Boehm-system clarinet in B-flat (the so-called Plain Boehm) as a starting point. The outcome was the Full Boehm clarinet (see Fig. 7), which included the following additions to facilitate the execution of difficult passages on standard models:16

1 A seventh ring for the third finger of the left hand, to permit a forked-fingered chalumeau E-flat/clarion B-flat.

2 An articulated chalumeau C-sharp/clarion G-sharp, to permit the B to C-sharp and F-sharp to G-sharp trills to be made (the so-called G-sharp mechanism).

3 An extra touch for the second finger of the right hand is added in the lower joint, to permit chalumeau C-natural to C-sharp and clarion G-natural to G-sharp trills to be made.

4 A chalumeau A-flat/clarion E-flat lever for the left little finger, to permit an alternate fingering to the same key for the right hand.

5 A low E-flat key for the right little finger, to permit transposition of all notes of the clarinet in A.

Figure 7. Full

Boehm clarinet,

Selmer, Paris,

1932. Author’s

collection.

Part 2 will continue with a detailed discussion of the Gomez-Boehm clarinet.

Endnotes

1 J.G. Rendall, The Clarinet, 3rd ed. (London: Ernest Benn Limited, 1954), 110.

2 P. Weston, Clarinet Virtuosi of the Past (Corby: Fentone Music Limited, 1971).

3 Canadian clarinetist Harold Manuel Gomez (b.1946). He studied clarinet in Toronto with Abe Galper and later in Paris with Yona Ettlinger. He was the first clarinet of the National Ballet Orchestra and clarinet professor of the Royal Conservatory of Music and the Glenn Gould School, both in Toronto, Canada.

4 The following narrative uses information from Weston unless otherwise indicated.

5 P. Rubio, “Manuel Gómez: The Famous Spanish Clarinettist,” Revista Música, No 24 (2017), 79-97.

6 E. Halfpenny, “The Boehm Clarinet in England,” Galpin Society Journal, Vol. 15, (1977), 2-7.

7 M. Griffin, “10 August 1895: The first ever ‘First Night of the Proms,’” 2015, retrieved February 13, 2017 from www.royalalberthall.com.

8 It is a section of the piece Fantasy on themes of Verdi’s Rigoletto for clarinet and piano by the Italian clarinetist and composer Luigi Bassi (1833-1871).

9 The registration was made for The Gramophone & Typewriter Ltd. No. 6030. The recording can be found on the CD Historical Recordings, Vol. 1 of the British label Clarinet Classics (CC 0005, 1993).

10 I am grateful to Charlotte Kennedy Domínguez, Trinidad Gómez’s great-great-granddaughter, for her detailed information about the Gómez family tree.

11 Rendall, The Clarinet, 110.

12 Weston, Clarinet Virtuosi of the Past, 243.

13 A. Baines, The Woodwind Instruments and Their History, 3rd ed. (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1957), 119.

14 P. Rubio, I. López and J. Sanz, “Entrevista a Máximo Muñoz,” Revista ADEC, No. 9 (2011), 5-10.

15 J. Menéndez, 32 estudios de perfeccionamiento, (Madrid: Editorial Música Moderna, 1953).

16 Plain Boehm clarinets with one, two or more of these additions were also made and can be found even today in the catalog of some clarinet makers. On the other hand, in the German area of influence, clarinets provided with the low E-flat were also made by the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th.

Part II – The Gomez-Boehm Clarinet

The name Gomez always conjures up everything that was best in clarinet playing in this country a little before my time.1

– Eric McGavin

Manuel Gómez c. 1899. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

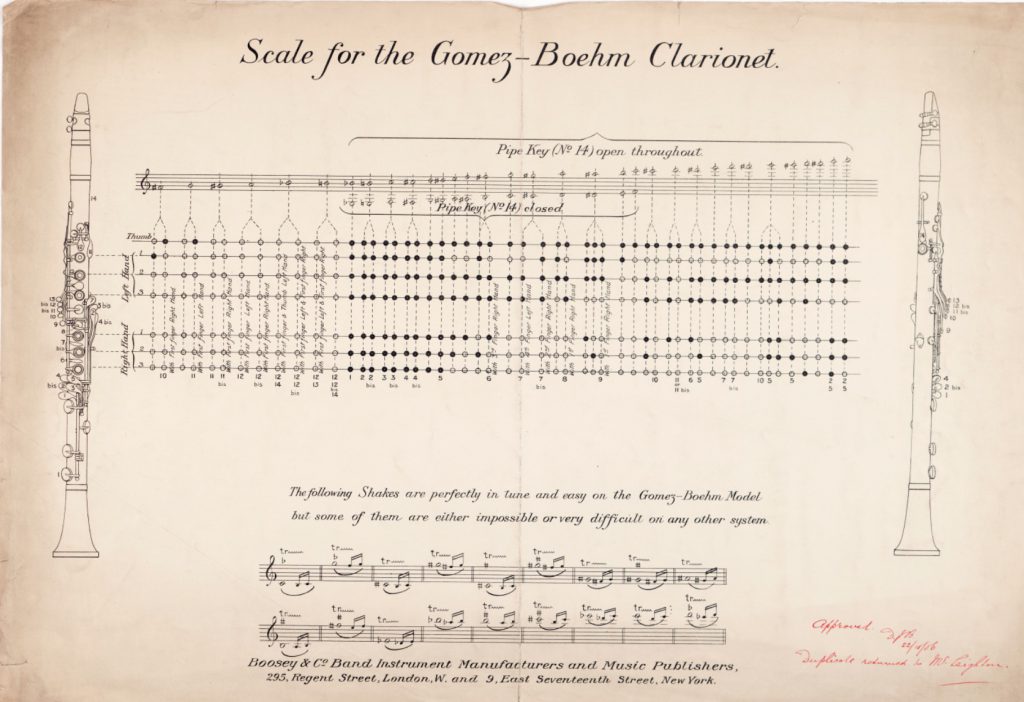

In 1899, a new model of clarinet developed under the guidance of Manuel Gómez was added to the production line of the English maker of wind instruments Boosey & Co. This clarinet was part of the numerous improvements and new designs that Boosey & Co. made during the last decades of the 19th century.

Boosey made three new models between 1883 and 1895: the Clinton system designed in collaboration with the professional player George Clinton, the first Boosey clarinet with Barret action, and their first Boehm clarinet. […] However, Boosey made no more until 1899 when they produced a new Boehm model that was designed in collaboration with Manuel Gomez.2

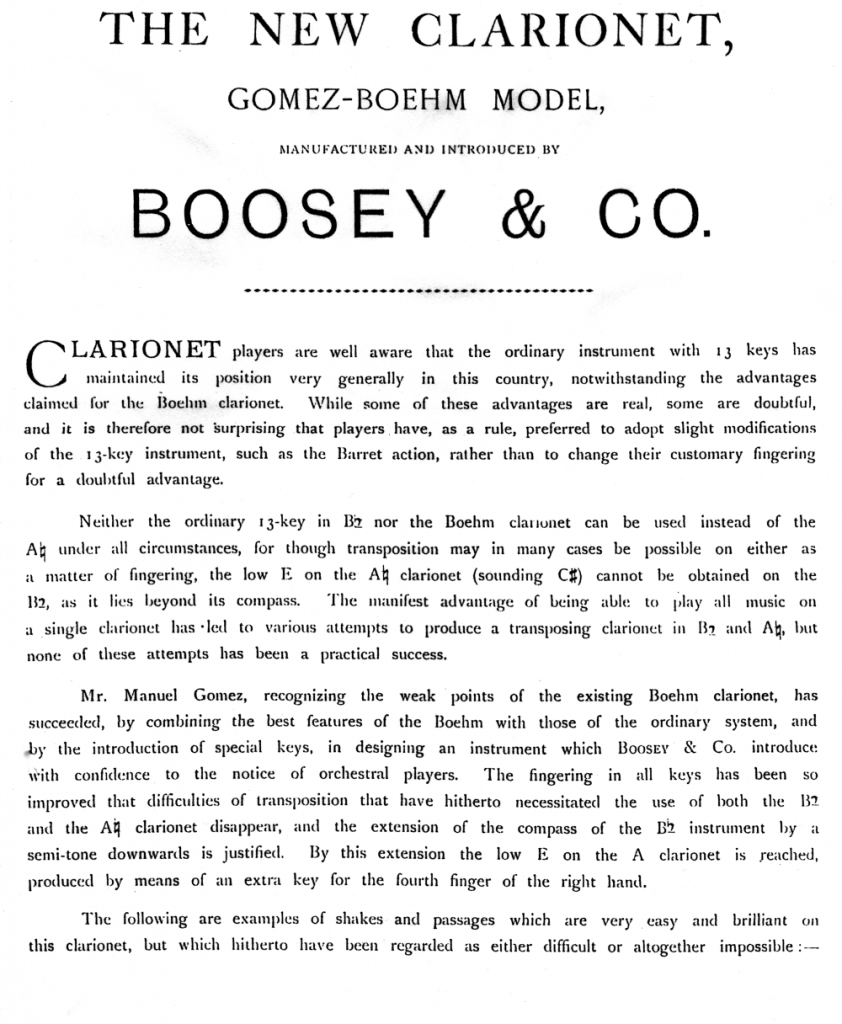

The information currently available about the Gomez-Boehm clarinet is scarce and rarely goes beyond declaring its existence, but the Manuel Gómez family has what seems to be a Boosey and Co. clarinet booklet from c.1900 in which this special model of clarinet is described. This is an extended text giving us the objectives of the instrument and, at the same time, an interesting overview of the situation of the clarinet in England during the last years of the 19th century (see Fig. 1). Thanks to it, we know that the “ordinary 13-key” clarinet was the most common choice by the English players during those years. This model, with utmost certainty, refers not to the clarinet conceived by Iwan Müller (1786-1854) in 1812, but to the one with 13 keys and two rings developed by Eugène Albert (1816-1890) in 1862, the so-called Albert system (see Fig. 2).

Figure 1: Boosey & Co. booklet, pp. 1 and 2, c.1900. Gómez family archive, Toronto, Canada.

An important part of the text is devoted to the practice of transposition, describing the inconveniences for this task of the standard 13-key (Albert) and Boehm clarinets in B-flat. A “transposing clarinet” (combination clarinet) is also mentioned: during the last decades of the 19th century and the first of the 20th, several attempts were made to combine, through movable tubes inside of the bore, both the B-flat and A clarinet in a single instrument. Nevertheless, as the text states, none of the numerous proposals were completely successful. Thus, the Gomez-Boehm clarinet is presented to the orchestral players as the perfect solution.

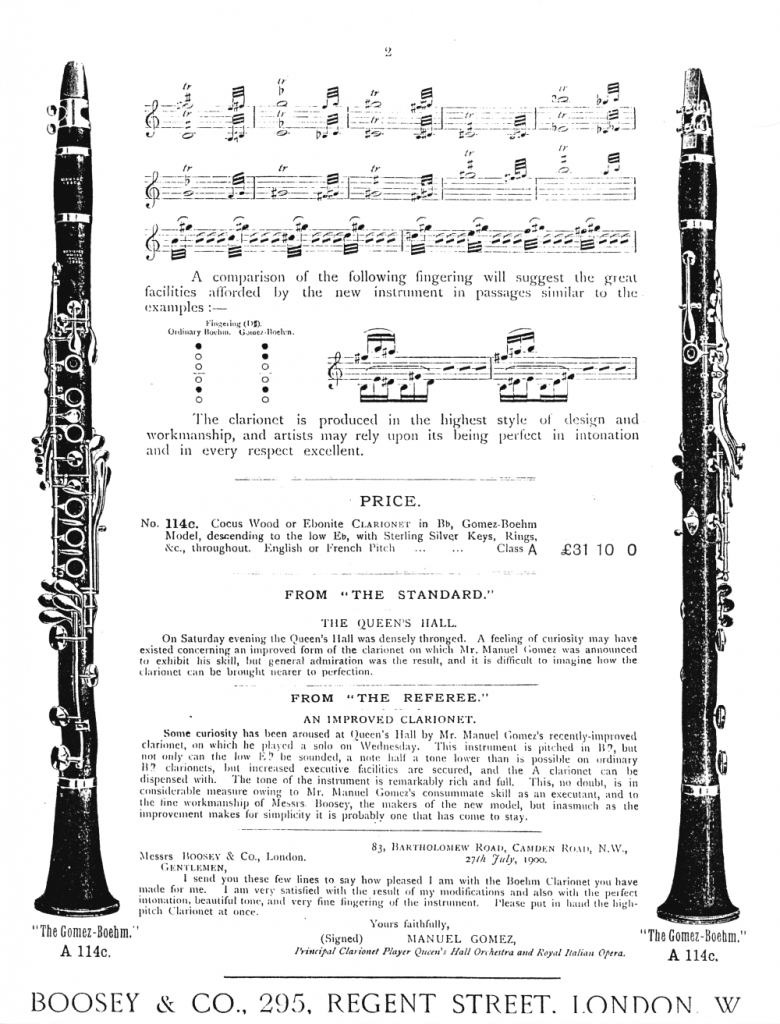

At first look, the Gomez clarinet appears to be very similar to a Full Boehm clarinet: it has the seven rings, the G-sharp mechanism with its extra touch between the fourth and fifth ring, and the low E-flat key (see Fig. 6). Closer examination, however, reveals some interesting and unusual features. Out of the five Full Boehm additions to the Plain Boehm mentioned in the previous article (Part I), only three of them are present. As with many other improved models, the Gomez-Boehm has the upper and lower joints made in a single piece of wood. This always simplifies the mechanism connections between the two joints and allows the C-sharp/G-sharp tone hole to be placed in its proper acoustical position.

The lower joint section

This section will not need much explanation since it is very similar to the same part of a Full Boehm clarinet: it has the usual keywork of the Plain Boehm plus the low E-flat key and the extra touch for the C-sharp/G-sharp – though this touch has its own tone hole and it is not connected with the rest of the G-sharp mechanism.3 However, it lacks the A-flat/E-flat lever for the left little finger and there is an unusual key above the fourth ring activated with the first finger of the right hand. This key (number 8 in the fingering chart, see Fig. 7) opens a hole in the right part of the instrument close to the ring finger’s vent. It was devised for playing trills from chalumeau C to D and C-sharp to D-natural, and the twelfths above. The long keys for the left little finger are mounted in a single axel, like the standard Boehm clarinets of those years.

The upper joint section

The exceptionality and originality of the Gomez clarinet undoubtedly lies in this section. If you are a Boehm player, the first thing that probably draws your attention is the unusual number of side keys: five instead of the expected four. The G-sharp mechanism is placed in its customary position, but the left-hand cross key for the E-flat/B-flat is missed.4 Moreover, the second ring has no satellite pad cup, and, on the contrary, the third ring has one. Testing the clarinet, we find out that although it has three rings, there is no forked E-flat/B-flat. When the clarinet is examined, we can notice that both rings are lightly sprung to open but the rod that holds them is connected with a heavy spring which keeps them closed. When the touch for the E-flat/B-flat side key

or any of the lower joint rings is pressed, the strong spring is hindered and both rings with the satellite pad cup open.

This mechanism corresponds clearly to a Barret action.

The Barret action

The Barret action is named after the oboist Apollon Barret (1804-1879) who worked closely with the Parisian oboe maker Frédéric Triébert (1813-1878). This mechanism was developed for the oboe shortly before 1850, and in the 1870s was adapted to the clarinet. For the simple-system clarinetist, the Barret action had numerous advantages. This mechanism consists of two rings for the index and ring finger, each one controlling a satellite pad cup. These pad cups produce the notes E-flat/B-flat and F/C. The rings and their satellite pad cups are sprung to open but a heavy spring keeps them closed unless the touch of the side key is pressed. When this occurs, both rings and their satellite cups rise allowing a varied number of combinations for the left hand notes. The Barret action can be found on the modern oboe, the so-called conservatory model, used throughout most of the world today. On the clarinet it remained in use, as an improvement to the Albert system or as a part of further clarinet systems, until as late as the 1950s. Fig. 3 shows a Robert Cubitt clarinet with Barret action and the patent C-sharp mechanism. Fig. 4 shows a Clinton system clarinet, and among its qualities, the upper joint has also the Barret action.

The side keys

Regarding the side keys, as said above, the Gomez clarinet has five keys instead of the customary four:

1 In contrast to the standard Boehm clarinet, the E-flat/B-flat side key (fingering chart, key 9), does not directly control a tone hole, since it is part of the Barret action that activates the mechanism as described beforehand.

2 Going up, the next key (fingering chart, key 10) has the same function as the F-sharp side key on the standard Boehm clarinet, but it moves alone, without pulling the E-flat/B-flat side key. It is good also for trills between E/F-sharp and their twelfths.

3 The next one (fingering chart, key bis 11) activates a hole that is placed at the same height as the throat A key (fingering chart, key 11). Alone, it produces a throat G-sharp (a useful trill between G and G-sharp is possible), and adding key 11, a good throat A is emitted. So, it is also a suitable key for trills between G-sharp and A.

4 Keeping on (fingering chart, key bis 12), this key is placed almost at the same height as the 10bis key (Klosé’s numbering) on the standard Boehm clarinet. Pressing the touch, its drags the underneath key with it (bis 11) producing a throat A. Thus, this is an intended key for trills between throat G and A, or throat A and B-flat. Linked with the standard throat A key, it produces a pretty good throat B-flat.

5 The last one (fingering chart, key 13), is similar to the 11 key (Klosé’s numbering) on the standard Boehm clarinet.

As we have seen, the Gomez clarinet has some unusual features, but in fact no more than many of the hundreds of clarinet designs created over the years. Furthermore, clarinets with Barret action have been quite common between at least c.1870 and c.1950. So, what makes the Gomez-Boehm clarinet different? Why is it so special? And what is its place in the clarinet history? On one hand, it can be included in the group of clarinets designed to play on one single instrument the orchestral parts written for clarinets in C, B-flat and A (like, for example, the Full Boehm clarinet and the late Romero system clarinet models); and on the other hand, its originality and exceptionality lies in the combination of Boehm fingerings with the Barret action, a device conceived initially for non-Boehm instruments. This union, to my knowledge, made this model unique in clarinet history. This mechanism, additionally, has an elegant design of outstanding quality and inventiveness, combining the two main versions of the Barret action in one.

Figure 2: Albert system clarinet (simple system). 13 keys and two rings. Eugène Albert, Brussels, c.1870. Author’s collection.

Figure 3: Albert system clarinet (simple system) with Barret action and the patent C-sharp. Robert Cubitt & Co., London, c.1890. Author’s collection.

Figure 4: Clinton system clarinet, Boosey & Co., London, c.1909. Author’s collection.

Figure 5: Albert system

clarinet (simple system)

with Barret action and the

patent C-sharp. Hawkes

& Son., London, c.1910.

Author’s collection.

Figure 6: Gomez-Boehm clarinet, Boosey & Co., London, 1899. Museo de instrumentos del Real Conservatorio Superior de Música de Madrid.

David James Blaikley

If we look back to the history of the woodwind instruments, behind the proposal of a player to improve their instrument there has been always a skillful maker-technician-designer that was able to shape those ideas. To this rule there are at least two illustrious exceptions, both respected musicians and makers gifted with an enormous talent for inventiveness: Adolphe Sax and Theobald Boehm. But in general, it usually happened as follows: a player feels that the instrument could be perfected, conceives a series of improvements and goes to a woodwind builder to make the ideas come true. With the Gomez-Boehm clarinet we know already the name of the clarinetist, but the designer behind this special instrument deserves to be mentioned: David James Blaikley. Strauchen-Scherer and Myers give us some details of his biography in their article about the collection of instruments of Boosey & Hawkes:

David James Blaikley (b. 13 July 1846, d. 29 December 1936) was the most prominent figure in British wind instrument manufacture at the end of the nineteenth century. The son of a portrait painter, he worked for Boosey & Co. from 1859 to 1930, […] As factory manager from 1873 to 1918 he was responsible for many improvements, inventions and the development of new models by Boosey & Co. In his final years with the company he was in charge of research and development. He contributed to the advances being made at the time in the science of musical acoustics.5

Today, Blaikley is well-known in the brasswind world thanks to his introduction of “compensating pistons” that changed the design of low brass instruments; but his involvement with woodwind designs, especially clarinets, is less recognized. He collaborated with some of the leading clarinetists of his time, Clinton and Gómez among them, and he had a significant influence in the design of the celebrated 1010 model, an icon of the firm until the demise of Boosey’s clarinet manufacturing.

Figure 7: Fingering chart for the Gomez-Boehm clarinet, approved by D. J. Blaikley. London, Boosey & Co., 1906. Courtesy of the Horniman Museum.

The Gomez-Boehm left-hand configuration

At the end of the 19th century, Manuel Gómez had already been in England long enough to know the particularities of the clarinet world in the U.K. Although the Boehm system clarinet was gradually gaining popularity among the young players, the trend towards that change was not clear yet; Gómez doubtless knew very well the preference among the majority of the British clarinetists for the simple-system clarinet and one of their favorite add-ons: the Barret action. Conversely, Gómez would also be well aware of the three clarinet models that appeared in London during those years. In 1883, shortly before the arrival of Gómez to London, Boosey & Co. began the production of the Clinton system clarinet, the result of a collaboration with clarinetist George Clinton. In 1891, a “combination clarinet” was patented by James Clinton, George’s younger brother. A few years later, a demonstration for this clarinet was arranged and Manuel was one of the clarinetists invited to perform.

Manuel took part at the Royal College of Music on 7th July 1896 in a demonstration of the Clinton-Combination-Clarinet. This clarinet was an attempt to do away with the necessity of having two instruments and was after Manuel’s own heart; for he never used anything but a B-flat clarinet himself.6

In 1895, George Clinton developed his earlier clarinet system, giving way to the so-called Clinton-Boehm system, also made by Boosey & Co. But, regardless of its name, it has little in common with the Theobald Boehm ideas.

The name “Clinton-Boehm” is perhaps an unfortunate choice, as “Boehm” in this case does not refer to the acoustics of the Boehm System clarinet. Instead, the instrument is mostly identical to the aforementioned Clinton System but the touch-pieces for the fourth finger of each hand are disposed like the Boehm system.7

The Clinton system and the Clinton Boehm were essentially just two new attempts to improve the simple system clarinet while retaining its fingerings as much as possible. Furthermore, the Clinton-Combination clarinet was not completely satisfactory and never got off the ground. So, around 1898 Manuel Gómez probably felt that the time had come to make his ideas come true. Thus, the first requirement to be met was obvious: it must be a B-flat clarinet with the low E-flat key able to play all the orchestral parts written for clarinets in C, B-flat and A. The next step: to design special keys improving the fingering in all tonalities; this would explain the unusual number of side keys and the existence of the odd key number 8. And last but not least was the addition of the Barret action advantages to a Boehm clarinet.

The idea of incorporating the Barret action into a Boehm clarinet must have been attractive for Boosey & Co. The bulk of its customers were among British players and in the colonies, and this project was possibly seen as an opportunity to introduce a Boehm clarinet to clarinetists familiar with that mechanism. Once at the design table of the factory, it is evident that the designer knew perfectly the Barret action and its variants. One of his most remarkable findings was to combine two of them in one (its activation with both a side key and the lower rings). To realize that, a connection through a key lever pivoted at its center was designed to transfer the movement from the lower joint to the upper one. The upper part of this lever is inserted into a cavity of the E-flat/B-flat side key, thus activating it whenever any of the rings of the lower joint is pressed. By means of this ingenious solution, the advantages of both Barret action versions were achieved.8

Simultaneously, the other challenge faced was to adapt into a Boehm clarinet the non-Boehm fingering inherent to the Barret action. To understand the process, we must bear in mind that the Barret action was originally conceived on the oboe to automate the closed C and B-flat keys by a single touch. Those notes on non-Boehm woodwind instruments (except bassoons) are placed between the left index, medium and ring fingers. Additionally, virtually all non-Boehm clarinets have in common that the hole for the left index finger gives F-sharp/C-sharp instead of F/C, and – this is important! – the left middle finger is over the E/B hole instead of the E-flat/B-flat hole.9 So, in the Boehm system, on the contrary, the left middle finger is over the E-flat/B-flat hole instead of the E/B hole. Consequently, if the Boehm clarinet already gives the F/C notes through its left index finger hole and the left middle finger is over the E-flat/B-flat hole, it makes clear that adding a mechanism conceived to get these notes has little sense.

What did Blaikley do? Maintaining the Boehm fingerings for the thumb and the index finger, he moved the middle finger hole to its non-Boehm position, i.e., over the E/B hole. To preserve the “Boehm touch” (the feeling of the hands over a Boehm clarinet), the E/B hole was slightly positioned down in the tube and enlarged. The satellite pad cup to get F/C is no longer necessary since that note is produced through the index finger hole thanks to its Boehm configuration. So, now the only necessary satellite pad cup is the E-flat/B-flat one placed between the second and third hole (see Fig. 6). The Barret action variants are numerous and there is at least one Barret model in which the F/C satellite cup is also absent (see Fig. 5). In this case, the F/C hole is placed on the side of the instrument and controlled by both the side key and the left middle finger’s ring.

After testing the clarinet, I could verify that the result, both in tuning and tone quality, was completely satisfactory.10 Since the F/C is already produced through the first hole, the second ring lost its initial task of controlling the satellite pad cup of that notes. But nevertheless, the ring was maintained as part of the keywork with its independent spring linked to the rest of the Barret action. A possible reason why this ring remained was that its chimney could help the middle finger to cover the pretty wide diameter of the second hole. Other possibilities are that it was not removed rather for both aesthetic and commercial reasons: a clarinet with rings in all its finger holes minus the second one would have seemed (and felt in the hands) weird.11 Besides, it would have been difficult for the potential customers to associate the new model with the Barret action and the Full Boehm clarinets.

Surviving Gomez-Boehm Clarinets

Boosey & Hawkes has a characteristic that distinguishes it from almost all other wind instrument makers in history: thanks especially to the so-called “workbooks,” most of the records of its activity has

been preserved.

The extant workbooks of B&Co. [Boosey & Co.] and then B&H [Boosey & Hawkes] are comprehensive and meticulously recorded. They span the period of nearly 130 years and contain a complete record of brasswind from 1868 to 1985, and an almost complete record of woodwind from 1857 to 1986. Each instrument was noted individually with information about it, with in some cases the worker’s hours and pay, until the introduction of mass-production.12

According to Howell’s research, three Gomez-Boehm clarinets were made before 1904. Between 1904 and 1912 the production is unfortunately unknown, since the workbook that includes those years is lost. After 1912 another three Gomez-Boehm clarinets were recorded. One of the Gomez clarinets preserved corresponds to the time lapse of the lost workbook, because its serial number has been dated c.1908. Thus, at least seven Gomez-Boehm clarinets were made. Currently, only three Gomez-Boehm clarinets have been found in museums and private collections.13 So, it is likely that some of the other Gomez clarinets made will appear in the future.

The Madrid Gomez-Boehm Clarinet

In April 2017, Canadian clarinetist Harold Gomez (grandson of Manuel Gómez) and his wife Nadia Potts visited Spain for an event at the Madrid Conservatory to inaugurate an exhibition dedicated to Manuel Gómez. Harold was, of course, the central figure, and during the act an extraordinary occasion took place: the donation of Manuel Gómez’s clarinet to the Museum of the Madrid Conservatory.

Figure 8: April 19, 2017. Act of donation of Manuel Gómez’s clarinet to the Museum of the Madrid Conservatory. From left to right: Harold M. Gomez (Manuel Gómez’s grandson), Ana Guijarro (Principal of the Conservatory) and the author.

Manuel Gómez’s clarinet, an instrument that belonged to a former student of the Madrid Conservatory, resides now in the museum beside another remarkable instrument, also a bequest from a former student: Pablo Sarasate’s Stradivarius violin. In the showcase, the Gomez-Boehm clarinet is currently on display accompanied by a Romero system clarinet, the only one preserved in Spain, and a unique experimental clarinet by Adolphe Sax. As a clarinetist, if you are in Madrid, a visit to the museum is worth it.

Acknowledgements

To Harold Manuel Gomez and his wife Nadia Potts for kindly putting at my disposal a lot of information and family file documents; my sincerest gratitude to both of them for the donation of Manuel Gómez’s clarinet to the Museum of the Real Conservatorio Superior de Música of Madrid. To Charlotte Kennedy Domínguez for providing invaluable information about the Gómez family tree. To Peter Wardale for providing photos and information about the Francisco Gómez family. To Margaret Birley from the Horniman Museum. To Libby Rice from the London Symphony Orchestra Archive. To Mark Charette, Jocelyn Howell, Jonathan Krehm, Albert R. Rice, Fernando Jiménez, Fernando Gilgado, Saúl Pérez-Juana and all the staff of the Museum, the Library and the Historical Archive of the Madrid Conservatory for help and advice in the search of documents.

Endnotes

1 Letter from Eric A. McGavin, Boosey & Hawkes Education Advisor and Museum curator, to Harold M. Gomez, 16th April, 1970.

2 J. Howell, Boosey & Hawkes: The Rise and Fall of a Wind Instrument Manufacturing Empire, Vol. II (London: Unpublished Doctoral Thesis, University of London, 2016), 25-26.

3 This arrangement is not unusual in “early” Full Boehm clarinets, that is to say, the last decades of the 19th century and first years of the 20th.

4 The Gomez-Boehm clarinet preserved in the Horniman Museum does have that key.

5 B. Strauchen-Scherer and A. Myers, A., “A Manufacturer’s Museum: The Collection of Boosey & Hawkes,” Musique-Images-Instruments, No. 9 (2007) 147-164.

6 P. Weston, Clarinet Virtuosi of the Past (Corby: Fentone Music Limited, 1971), 243.

7 J. Joseph, “Clarinets of the Clinton Family,” Proceedings of the Clarinet and Woodwind Colloquium 2007, edited by Arnold Myers (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University, 2012), 75.

8 Another version of the Barret action, used in some oboes and flutes, is activated by the left thumb. See: J. L. Voorhees, Woodwind Fingering Systems (Hammond, Louisiana: Voorhees Publishing Co., 2000), 40-42.

9 The name of the holes refers to the note that comes out from them.

10 All the tests have been done with the Gomez-Boehm clarinet preserved in Madrid.

11 Nevertheless, some clarinets with unusual left hand ring configuration were made during the 19th century and early years of the 20th. At least six examples have been found, all from the ex-Shackleton collection and currently preserved at the Edinburgh University: A. Sax, c.1843 (one ring for the middle finger), Rudall, Rose, Carte & Co., c.1865 (one ring for the index finger), and three clarinets by J. B. Albert, c.1900 (one ring for the middle finger).

12 Howell, Boosey & Hawkes: The Rise and Fall of a Wind Instrument Manufacturing Empire, Vol. I, 22.

13 1) Museo de instrumentos del Real Conservatorio Superior de Música of Madrid, Spain. Serial number: 13719. Year: 1899. 2) Horniman Museum, London, UK. Serial number: 17543. Year: c.1908. 3) Private collection, USA. Serial number: 20054. Year: 1913. I’m grateful to Albert R. Rice for his help in locating the last of these examples and providing information about its characteristics.

About the Writer

Pedro Rubio is professor at the Real Conservatorio Superior de Música of Madrid. In 2007 he founded the publishing house Bassus Ediciones, whose principal objective is the restoration and retrieval of the Spanish clarinet repertoire of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century. He was one of the artistic directors of ClarinetFest® 2015 in Madrid.

Comments are closed.