Originally published in The Clarinet 51/3 (June 2024).

Copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

Taming the Tongue

In this collaborative article from the ICA Pedagogy Committee, adapted from their ClarinetFest® 2023 presentation “Articulation Bootcamp,” their collective approach to articulation provides a variety of perspectives, techniques, and common goals for effective and efficient articulation mechanics.

by ICA Pedagogy Committee: Jennifer Branch, Ricardo Dourado Freire, Joshua Gardner,

Julianne Kirk-Doyle, Corey Mackey, Osiris Molina, Pamela Shuler, Kylie Stultz-Dessent, George Stoffan, and Gi-Hyun Sunwoo

Articulation is one of the most difficult elements of clarinet playing to accomplish and to teach because we cannot see inside the mouth. In our early years as clarinetists, we often learn some components of articulation incorrectly. We therefore need to “Tame the Tongue”!

Incorrect articulation mechanics can include:

1 Huffing or stopping the air to create separation

2 Anchor tonguing: Tip of the tongue anchors on the lower teeth and the middle of the tongue tongues the reed

3 Tonguing on the roof of the mouth: a clicking sound will be heard behind the articulation

4 The tongue never leaves the reed but instead anchors to the reed and creates a subtone-type articulation

Elements for efficient articulation mechanics include air, tongue position, embouchure, voicing, and physical relaxation.

The Air Propels the Tongue (Jennifer Branch)

Playing an instrument is the ultimate exercise in multitasking. When we are focused on complicated keys, fingering passages, patterns, leaps, and articulations, our most important fuel, air, may disappear when needed the most. If focused entirely on the tongue, without sufficient air, articulation will be improperly fueled. Imagine turning on the water for a garden hose full-force: the water flows parallel to the ground. What happens if we slice the water with our hand? Does the water turn off or change pressure from its source? No. Similarly, articulation should interrupt the output of air but the wind itself will remain unchanged from the source, like the water from the garden hose.

Air Awareness (Pamela Shuler)

Arnold Jacobs, the famous former tubist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, was well-known for his breathing pedagogy. In Brian Frederiksen’s book, Arnold Jacobs: Song and Wind, Frederiksen states, “Next to problems with respiration, the most common problems with which students come to Jacobs are those concerning the tongue. The tongue is an unruly organ and has nothing to do with vibration, but can easily get into the air stream and negatively affect the tone’s production.”

Before looking at the placement, movement, and other specifics related to the tongue muscle, we must consider that the air can either support the tongue or constrict the tongue’s potential.

Utilize basic breathing exercises

During the inhalation and exhalation process of breathing exercises, consider the following:

1 Where is the placement of the mouth, of the tongue?

2 What is the state of the tongue muscle? Is it flexible or rigid?

3 Is there any unnecessary tension in the tongue, throat, or torso?

Through relaxation, organic breathing, and air awareness, tongue tension can be eliminated.

Voicing (Corey Mackey)

Voicing is the term used to discuss the shape of the air column inside the oral cavity before the air enters the clarinet. There are different opinions on voicing and how much to be discussed with students. A simple approach is for students to understand that when certain notes lack response or are not as clear as they want, voicing can be the problem. Correct tongue position can happen early on in the clarinet journey.

Relaxing the throat

In order to have a relaxed throat, think of a whispered “H” as in HA. Say SHH with your tongue. Can you feel the top back molars with the sides of the tongue? Is the tongue forward?

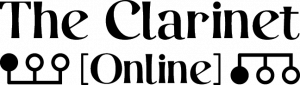

Play a low C, press the below keys. If they can get the G and E out, their voicing is good for most of the clarinet. If the G comes out, but the E does not, their tongue is too low or back. Have them use fast, cold air, and angle the air a bit higher and think SHH with the tongue. Exercise 1 is taken from Fred Ormand’s Fundamentals for Fine Clarinet Playing.1

Example 1: Voicing exercise from Fred Ormand’s Fundamentals for Fine Clarinet Playing

The tongue is an Unruly Muscle (Osiris Molina)

It is important to realize the tongue is a muscle, and muscles can be improved through persistence and patience. A daily articulation regimen focused on proper mechanics is the best way to ensure long-term success. Like any muscle, the tongue works best when proper form and repetition are adhered to. Articulation and finger technique work similarly—the closer the tongue is to the reed or fingers to the tone holes, excess motion is minimized and efficient mechanics are achieved. When a student plays a predominantly slurred passage, it is often fine, but when the tongue is added, things can go haywire! Problems can occur, like unsynchronized tongue and finger coordination, heavy, uncontrolled, or imprecise articulation and more. Fast articulation is a result of physical relaxation, a consistent air stream, and a relaxed tongue that minimally touches the reed and remains close to the mouthpiece.

Embouchure (Gi-Hyun Sunwoo)

An efficient, well-formed embouchure is essential for good articulation mechanics. The lips should pronounce an “oo” vowel and seal around the mouthpiece. The position of the tongue should utilize an “ee” sound internally. Pronouncing a combination of the “ee” and the “oo” sound as “eu” will maintain proper airflow and voicing control.

Extension of the Long Tone (George Stoffan)

Effective articulation begins as an extension of a long tone. When a long tone is played, it is important to sustain the air column with consistent air speed to allow for a more even tone quality and dynamic over the length of the note. The air column is shaped through effective voicing. The front portion of the tongue should be brought forward in an arched position, in a setting that can be described as “poised.” By having a sustained singing air column shaped by tongue placement and a firm outer embouchure, the tone will be centered, clear, and even. These tone production elements are essential for good articulation. This is where the “tip-of-the-tongue to the tip-of-the-reed” expression we often hear is important. Legato articulation is achieved when we produce an effective long tone and simply touch the tip of the tongue to the tip of the reed. The touch to the reed should be followed by a “release” from the reed.

Tongue Placement (Gi-Hyun Sunwoo)

Articulation is often called an attack. Because the mouthpiece and reed are inside the mouth, articulation mechanics involve a stop of the reed vibration with the tip of the tongue. Separation is created when the tongue is “released” from the reed. To stop the sound, only a small amount of tongue pressure is necessary to cease the vibration of the reed.

Tip of the Tongue Touches the Tip of the Reed (Joshua Gardner)

Tongue placement on the reed is critical for clarity and speed—touching too low can cause pitch noise artifacts in your sound; too high is rarely a problem if the mouthpiece is at an appropriate angle.

1 Identify the tip of your tongue.

- Use a fingernail to scratch the tip of your tongue, preferably in front of a mirror.

- Is this where you thought it was?

- Is it where you make contact with the reed? Many people think their tongue tip is further back than it really is.

2 Stick out your tongue and place the tip of your reed on your tip that you just identified.

3 Bring your mouthpiece into your mouth without removing your tongue from the reed or moving it.

4 Form your embouchure.

5 Compress your air as if you are about to play.

6 Release the reed so you can blow that compressed air through the instrument.

7 Touch the tip of the reed again to interrupt its vibrations. Keep your air compressed at all times!

- Try this several times, making sure you’re using the tip of your tongue to touch the tip of the reed.

- Try this process again, but stop the reed and leave your tongue on the reed.

- Remove your mouthpiece from your mouth, keeping your tongue on the reed to check tongue placement.

See this video of what articulation looks like inside the mouth.

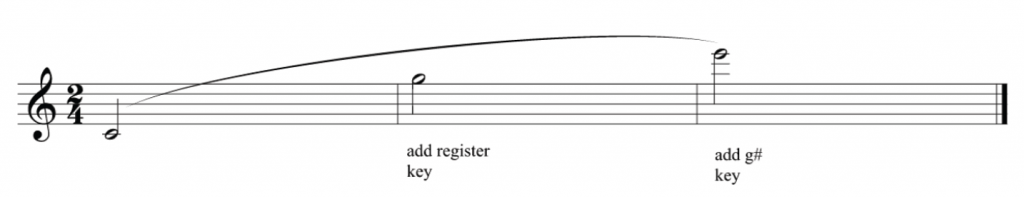

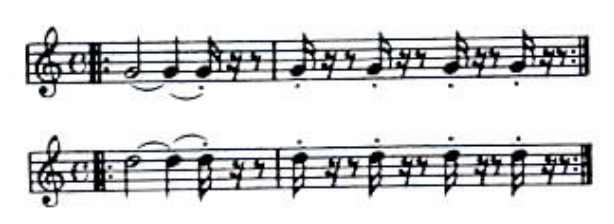

Tonguing Exercise 1

Exploring the Tip-to-Tip Articulation (Ricardo Dourado Freire)

A playful way to explore tongue position during clarinet articulation looks back to the historic embouchure from the 18th century with the reed facing up or on top, more like a double reed. Players will experience the sound production with the upper lip, without pressure from the bottom lip or the jaw. Playing with the reed on top will require a change of the mouthpiece angle in the mouth and promote placement of the tip of the tongue to the tip of the mouthpiece. This will encourage an internal reposition of the tongue touching lightly on the tip of the mouthpiece. Practice with the reed on top for a short period of time, no more than five to eight minutes, then return to your regular embouchure with the reed on bottom and maintain the same tongue position to achieve tip-to-tip articulation.

Interruption Method (Joshua Gardner)

We cannot see the tongue when we articulate, and most of us are not great at perceiving that our tongue is doing when we are playing (or speaking, for that matter!). So, we need an indirect way of assessing our accuracy when touching the reed.

1 Play a low C and gently touch the reed with the tongue (on the bottom edge of the reed tip with the tip of the tongue) while maintaining normal air pressure. Have a tuner nearby.

- If too much tongue force is used, the sound will stop and it may be impossible to keep air flowing into the instrument.

- If air cannot pass through the mouthpiece, far too much pressure is being used.

- If air can pass, but there is no reed vibration, the tongue may still be pressing too hard into the reed, or too much tongue is touching the reed.

- Only a very small portion of the tongue needs to contact the reed tip. I tell my students to let only a few taste buds gently meet the reed.

- We can use the tuner to determine the accuracy or our “aim.” If your tongue is touching the edge of the reed, your pitch will go sharp. If you’re touching too far below the reed tip, your pitch will go flat. If your pitch rises, proceed to Tonguing Exercise 1.

2 Tonguing Exercise 1 applies interruptions to a gradually accelerating rhythmic pattern that will allow you to apply the technique gradually to faster articulation passages.

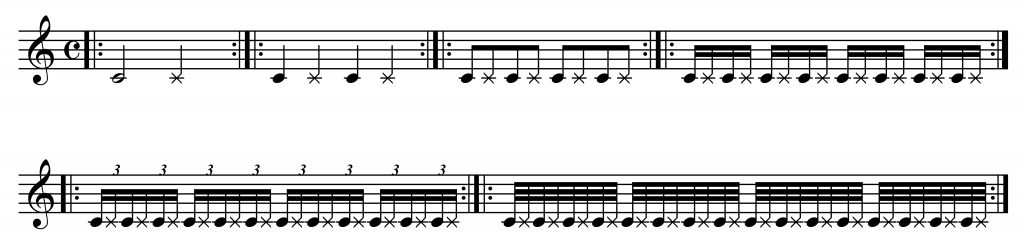

Once comfortable with Exercise 1, begin to practice Exercise 2.

- The tongue motion, contact pressure, point of contact (tip of the tongue to the bottom edge of the reed’s tip), and air pressure are identical to that practiced in Exercise 1.

- Initially, the tempo should be rather slow, allowing the interruption technique to be applied to this new context. Once it becomes comfortable, the tempo should be increased gradually over several weeks.

- Even after mastering Exercise 1, continue playing it before practicing Exercise 2 to reinforce proper tongue-reed contact as well as air support.

- You can use any note pattern you’d like, as long as it covers a sufficient range. It is important to practice articulation throughout the clarinet’s full range.

Troubleshooting

| Symptom | Problem | Solution |

| Single Articulation | ||

| “Dirty” articulation | Too much tongue touching the reed; tongue touching too low on reed; reed too high | Tip-to-tip articulation style; regular practice; adjust reed to align with mouthpiece tip |

| Cannot articulate above staff | Too much tongue movement, tongue touching too low on reed | Maintain a more constant tongue shape (think vowels) during articulation; reinforce tip-to-tip tongue-reed contact |

| Slow articulation | Stopping air, too much tongue movement, not enough practice | Maintain constant air pressure—the tongue stops the reed not the air; maintain arched tongue shape; regular articulation practice |

| Undertones, especially above staff | Tongue touching too low on reed, incorrect tongue shape | Tip-to-tip articulation style; address voicing |

| Pitch Scooping | Embouchure “chewing,” tongue touching too low on reed | Keep embouchure still (use mirror); reinforce tip-to-tip tongue-reed contact |

Tonguing Exercise 2

Vocabulary of Articulation (Julianne Kirk Doyle)

Everyone is built differently with various alignments of the teeth, jaw, lip size, oral cavity shape, and tongue size and placement. Articulation syllables can be personalized to what works for each player but with a few common goals. The tongue should remain high in the mouth and move minimally. Syllables to achieve this will vary player to player. For longer articulations it helps to explore sounds that allow ease of movement such as Thee, Thoo, Nee, Noo, Lee, Loo. When clear front or accented articulation is required, it helps to explore Tee, Too, Dee, Doo syllables. When we approach staccato articulations, adding a “t” to the end of the syllable of choice will allow for the clipped end and sound interruption. Articulation should be as effortless as speaking.

Staccato (Kylie Stultz-Dessent)

Developing proper staccato technique through the various registers on the clarinet is an essential skill that takes time and patience to acquire. It requires careful isolation of the tongue muscles from the lip and chin muscles—a coordination unique to wind playing. Daily activities such as eating and talking do not require these muscles to be independent.

When starting a staccato note, it is crucial to begin the note with the tongue on the reed. The airstream should be pressurized behind the tongue and the embouchure must be engaged. To initiate the sound, simply pull the tip of the tongue off the tip of the reed. If the airstream is pressurized and the embouchure is engaged, the note should respond immediately. To stop the sound, the tip of the tongue returns to the tip of the reed. Practice this coordination in front of a mirror. The embouchure, neck, and chest should remain motionless. The length of the staccato note is determined by the duration of time the tongue spends off the reed. To play a very short note, the tongue returns to the reed almost as soon as it leaves!

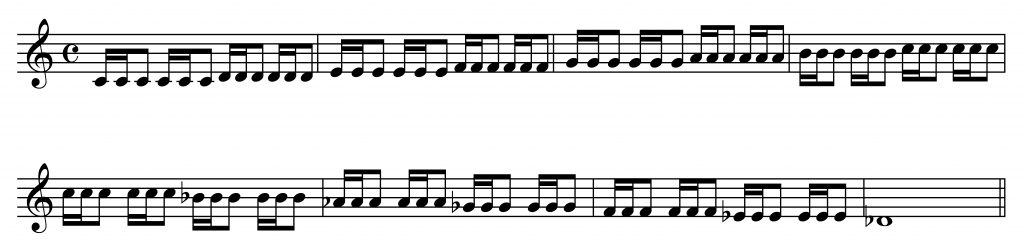

A wonderful exercise for developing staccato technique can be found in the third chapter of Daniel Bonade’s Clarinetist’s Compendium. The exercise begins with an open G that is stopped by the tip of the tongue being placed on the reed. Although no sound is being produced, it is imperative to keep the air pressure constant behind the tongue. Remove the tongue to start another note and repeat this process until you become familiar with the coordination. Once you are able to achieve a clear start and end to each note, Bonade introduces a series of short, staccato notes using the same principle. A sample of this exercise can be viewed below. When working through this exercise, prioritize consistency and clarity for each of the notes you produce. Be careful to not use too much tongue force on the reed, which can result in a “thwacking” sound. Use a mirror to watch for any unnecessary chin, lip, and neck movement. Begin the exercise on notes that are comfortable to produce such as open G. As you start to achieve consistent attacks and ends of the notes, expand the exercise to work through various registers. Pay attention to what is required for each of the registers.

Mastery of tonguing fundamentals is essential to produce clean, articulate, and expressive performances. It requires attention to detail, proper positioning, and consistent practice to achieve proficiency in this aspect of playing.

Bonade Staccato Exercise

Endnote

1 Fred Ormand, Fundamentals for Fine Clarinet Playing, www.fred-ormand.com, 2017.

ICA Pedagogy Committee Mission

Our mission is to promote and provide sources of pedagogy to members of the ICA and the music community. Through our educational workshops and presentations, articles in The Clarinet, “Lunch and Learn” interviews, and collaborations with other ICA committees, we seek to provide diverse offerings for all ages and ability levels.

Comments are closed.