Originally published in The Clarinet 47/2 (March 2020). Printed copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

Audio Notes March 2020

by Kip Franklin

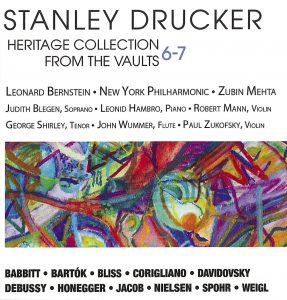

Stanley Drucker is unquestionably a titan of the clarinet world. In addition to his six decades with the New York Philharmonic (nearly five of them as principal clarinet), his career entails many commissions and recordings. A new double-disc set, Stanley Drucker: Heritage Collection 6-7, contains recordings of Drucker playing many of the most colossal works in the repertoire, as well as many important and rarely-played or obscure smaller works spanning the entirety of his career. That Drucker is on display as both a soloist and chamber musician throughout this collection is perhaps its most appealing element. In addition to standard concerti and concours works, the discs feature Drucker in duo and trio combinations with voice, cello and violin.

Stanley Drucker is unquestionably a titan of the clarinet world. In addition to his six decades with the New York Philharmonic (nearly five of them as principal clarinet), his career entails many commissions and recordings. A new double-disc set, Stanley Drucker: Heritage Collection 6-7, contains recordings of Drucker playing many of the most colossal works in the repertoire, as well as many important and rarely-played or obscure smaller works spanning the entirety of his career. That Drucker is on display as both a soloist and chamber musician throughout this collection is perhaps its most appealing element. In addition to standard concerti and concours works, the discs feature Drucker in duo and trio combinations with voice, cello and violin.

The first disc opens with a 1967 recording of Carl Nielsen’s monumental Concerto, Op. 57, with the New York Philharmonic conducted by Leonard Bernstein. Drucker’s interpretation is faultless and unblemished. He plays with divine technical precision and bittersweet lyricism throughout the course of the work, which according to the liner notes was recorded in essentially one take! Drucker’s expression of character and nuance is so refined, elegant and poised that one can easily forget that this work is one of the most demanding concerti in the repertoire. This recording is likely to become the standard to which all others are compared.

Milton Babbit’s Composition for Four Instruments begins with an extended clarinet passage that Drucker performs in an improvisational off-the-cuff manner. The work features a variety of instrumental timbres and techniques, resulting in a unique tapestry that resembles the pointillistic writings of Webern and Boulez. Valley Weigl’s Nature Moods ensues, with Drucker showcasing his ability to emulate the human voice. Each of the five movements in this work conveys a bucolic ambiance with perfectly interwoven counterpoint between the clarinet, voice and violin. The balance in this particular work is exceptional, with a clear distinction between melodic and accompanimental material and impeccable intonation of open intervals.

Mario Davidovsky’s Synchronism No. 2 calls for clarinet, flute, cello, violin and electronic tape. Drucker and his colleagues expertly achieve control of extreme dynamics and various timbral

combinations resulting in an interesting and ever-evolving tapestry of colors, textures and soundscapes.

Honegger’s Sonatine for Clarinet and Piano is equal parts meditative, sentimental and jazzy. Especially notable is the contrapuntal playing between Drucker and pianist Leonid Hambro in the first movement. Drucker’s phrasing in the second movement is remarkably poignant and his incisive articulation in the third movement is impressive.

Volume 6 concludes with Béla Bartók’s Contrasts recorded in 1954 – Drucker’s first professional recording. Here Drucker again conveys his utmost command of style. Pointed rhythmic gestures in the first movement, evenly controlled tone in the second movement and whirly 16th-note passages in the finale combine in a total tour-de-force for all players.

Volume 7 begins with Debussy’s Première Rhapsodie, Drucker’s first solo collaboration with the New York Philharmonic and Leonard Bernstein. The synchronization between Drucker and the orchestra is exquisite; one has the sense that he is somehow playing and conducting simultaneously. Drucker undauntedly masters the rapidly cascading arpeggios in the scherzando section and

conveys control and color in the more lyrical passages. This orchestration is a refreshing departure from the more traditional clarinet and piano version.

Like Nature Moods and Contrasts, Weigl’s New England Suite showcases Drucker’s aptitude as a chamber musician. Her writing allows each instrument solo passages while still creating interwoven and complex ensemble textures. Drucker’s mellow, deep tone makes this an especially memorable piece; at times it is contemplative and ponderous, and at others jubilant and capricious. As with Nature Moods, the intonation of perfect intervals is spot on. Weigl’s work would pair nicely with any of the better-known trios for clarinet, cello and piano by Beethoven or Brahms.

The following three works, Spohr’s Sechs Deutsche Lieder, Gordon Jacob’s Three Songs, and Arthur Bliss’s Nursery Rhythms, represent a collaboration between Drucker and soprano Judith Blegen for a recital in 1980. Each of these works demonstrates Drucker’s ability to emulate the human voice. All are enjoyable and explore a full gamut of characters, tonalities, and moods.

The Spohr is certainly a standout of the set owing to its harmonic depth and formal richness. Drucker and Blegen successfully merge the qualities of Schubert’s lieder and Brahms’s chamber music into a single, unified interpretation. Also notable is Drucker’s charming and witty playing in the final movement of Bliss’s composition, allowing him to depart from the seriousness inherent to late Romantic style and paint a more humorous, cartoonish caricature.

The final work on the album is a 1980 recording of John Corigliano’s Concerto, written specifically for Drucker and the New York Philharmonic. Drucker’s playing in this work is wholly transcendent and his ownership of his craft is on full display. His playing is convicted, unblemished and committed, always going far beyond the limit of what one would think is possible on the

instrument. From the liquid-like runs in the opening of “Cadenzas” to the acrobatic and nimble “Antiphonal Toccata,” Drucker’s agile command of all facets of his playing is captivating and dramatic. The recording itself is of extraordinary quality; Drucker’s sound is never covered or obscured by the mammoth forces supporting and surrounding him.

These albums are vital necessities for clarinetists of any level. Careful work has gone into mastering each track to be clear and devoid of any distortion inherent to some older recordings. Drucker’s playing is utter perfection, and the supporting musicians and ensembles on the album are equally skilled. Obviously, the large canonical works are reason enough to own this album, but perhaps more valuable are the expert performances of the lesser-known chamber works with voice and strings. The collection contains liner notes with interesting and informative anecdotes from Drucker regarding the recording of each piece, as well as notes from John Corigliano, Michael Skinner, François Kloc, and others. Listeners will thoroughly enjoy every aspect of these albums, and their value and quality is immeasurable and cannot be overstated. Obviously, any album bearing Drucker’s name is going to be a masterpiece, but because of the breadth of repertoire on these albums and their accompanying historical anecdotes, this collection in particular is an absolute must-have for all players!

Happy listening!

Comments are closed.