Originally published in The Clarinet 46/4 (September 2018). Printed copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

The Forgotten Pedagogical History of Multiple Articulation for Clarinet and Saxophone

by Eric Schultz

The clarinet is known for its glowing, singing tone quality and liquid legato. Things that are difficult on many other instruments, like large intervals and dynamics from piano all the way to niente, are more easily achieved on our beautiful instrument. Articulation, however, is something that does not usually come quite as easily. There may be several reasons why the clarinet struggles to match the natural articulation capabilities of other instruments.

Consider the string instruments – even with just a glance at an orchestral score, a wide variety of articulations beyond staccato are evident. More precise terms like détaché, spiccato, jeté, pizzicato, collé, martelé, and col legno have different sounds, and different methods of production that can be observed visually because the mechanisms of articulation are not hidden inside the mouth. The visual nature of the bowed strings is an asset in teaching and learning articulation that is not afforded to wind players.

As if this wasn’t enough of an advantage, the bow also allows for one articulated note per motion. With each stroke (upbow or downbow), the string musician can have a distinctly separate note. For the clarinetist, the ratio is half as favorable; the tongue must move in two directions (onto the reed, and rebound) for each articulated note.

Multiple articulation, also called double tonguing, effectively solves this issue.

Tonguing on the clarinet is commonly described with the syllable “ta.” Double tonguing allows for another articulation during the rebound of the tongue, lightly brushing the soft palate (or velum) with the back of the tongue. This can be practiced away from the clarinet by pronouncing the syllable “guh” or “kuh,” with vowel variations possible. By solving the movement-to-articulation ratio issue, this method effectively doubles the maximum articulation speed of the single-tonguing clarinetist in addition to infinitely increasing the endurance, which clarinetists will find useful for pieces like the overture to Smetana’s The Bartered Bride.

Double tonguing works without too many issues on the flute as compared to the clarinet. Many high school flutists and some talented middle school students approach the technique with success. There are several reasons for this. Many resources today, especially online, explain that the technique is difficult for clarinetists because of the reed in the mouth. Personally, I haven’t found this to be the case. In fact, any clarinetist who can successfully single tongue has already mastered the first half of this technique and can presumably already navigate the mouthpiece and reed successfully.

What these resources usually fail to mention is the critical importance of voicing on the clarinet. Voicing refers to the non-articulatory function of the tongue, especially as it relates to intonation and tone quality. For the clarinetist, the tongue position is comparatively much higher in the mouth (usually described as an “e” or Germanic “ü” vowel). It is worth mentioning that the saxophonist’s tongue position is also higher than the flutist’s, though the air is usually described as “warmer” than the clarinet. For the flutist, the tongue is generally low, relaxed, and soft. This low tongue position is maintained throughout the entire register of the flute, resulting in double tonguing just as facile in the upper register as it is in any other range.

As the clarinet leaves the clarion range into the altissimo, the tongue position becomes higher, and the pitch much more flexible. For this reason, the clarinet is capable of large pitch bends in the upper register. The flute is capable of pitch bending not through voicing, but by use of other methods such as covering more

of the embouchure hole or rolling of the headjoint.

This pitch flexibility on the clarinet is relevant to double tonguing because the back of the tongue is important in maintaining pitch, and multiple articulation necessitates movement in this region of the tongue. Even the smallest movement of the tongue can drastically affect the pitch in the altissimo register. This explains why the technique is noticeably easier on the bass clarinet than the E-flat (and helps to further refute the popular “navigation of the mouthpiece” claim of difficulty).

This is not to say the technique is virtuosic, or even all that difficult. It just requires a little bit of practice and experimentation. Recently, it seems that multiple articulation has been getting more attention from clarinetists. In fact, this issue of The Clarinet includes a review of Kornel Wolak’s excellent new text on articulation types, which includes several different types of multiple articulation. I was also fortunate to attend his lecture on articulation at ClarinetFest® in Belgium this past July. I think it is important to remember, however, that double tonguing is by no means new. It does have a history on the clarinet, and it’s worth mentioning that saxophonists, in particular, have been writing about the technique for at least a century now.

A Review of Pedagogical Materials

There is a particularly large volume of forgotten material about multiple articulation from the first half of the 20th century. This was the era of American jazz: Dixieland, big band, and swing music. Jazz groups were topping the Billboard charts and jazz musicians became pop stars. Many saxophonists and woodwind doublers achieved celebrity status during this time, several of whom utilized multiple articulation technique. Some saxophonists, like Al Gallodoro, did not publish significantly in written form, but left behind a wealth of audio and video recordings that are sure to inspire musicians curious about multiple articulation to this day. Luckily, however, it was common for jazz musicians during this time to publish for their fans, and many of them released method books. Because it seems that saxophonists were publishing more, and because it is possible for clarinetists and saxophonists to share many resources and adapt them, it is worth examining the saxophone and woodwind doubler method books from this period.

It is hard for today’s jazz and classical musicians to imagine the level of celebrity enjoyed by our predecessors almost a century ago. One such name is Jimmy Dorsey, who even appeared in Hollywood movies. He was a master of multiple articulation, which is evidenced by several recordings, including a particularly exemplary 1934 single by the Dorsey Brothers Orchestra titled Tailspin, which at the time of this writing is available on YouTube.

Dorsey included a very concise, matter-of-fact section on multiple articulation in his method book, the Jimmy Dorsey Saxophone Method: A School of Modern Rhythmic Saxophone Playing, which was released almost 80 years ago. Dorsey was also a clarinetist, though like many jazz players at the time, he played the Albert system.

Rudy Wiedoeft is another early 20th-century example of musician as celebrity. Long forgotten, scholars are only now recalling his importance. He played the “C melody” saxophone, similar to a tenor saxophone, but in concert pitch. Because of several film shorts and recordings demonstrating Wiedoeft’s extraordinary articulation capabilities (also currently available on YouTube), many scholars now assume that he was a master of multiple articulation.

There is no real support for this, however. In fact, Wiedoeft’s Secret of Staccato method book, though an excellent resource, makes no mention of multiple articulation. It is possible he mastered the technique and kept it secret to make his abilities seem more impressive. Quite a personality, he states in his method:

I am writing this book in the hope that my system will help you to single tongue sixteenth notes as fast as the metronome will go, 208. I would suggest your reading every word carefully. In fact, it might not be a bad idea to memorize it… After discovering this new system, I slowly increased my speed from 156 to 304 per metronome marking.

There is one last saxophonist worth mentioning in this context. Kenneth Douse was a violinist, though as a member of “The President’s Own” U.S. Marine Band at the time, he was required to play both a string and wind instrument. In short order, he became a saxophone soloist with the group. He developed a multiple articulation technique by listening to the trumpeters in the band, and his method book is devoted entirely to multiple articulation. How to Double and Triple Staccato: A Revolutionary System of Rapid Double & Triple Tongueing is truly one of the best on the subject to this day, though regrettably out of print. In the introduction, he compares learning multiple articulation to a single-legged man finally discovering he had a second after all. “The President’s Own” 1948 recording of Joseph De Luca’s Beautiful Colorado shows impressive mastery of the technique throughout the full range of the horn.

The history of multiple articulation has not been quite as well-recorded by clarinetists, though several living clarinetists utilize the technique. Martin Fröst comes to mind for his virtuosic recordings featuring the technique. Robert Spring is famous for his superhuman tonguing abilities, and published a great essay examining multiple articulation in The Clarinet almost 20 years ago. Since then, his student Joshua Gardner did excellent work in mapping the motion of the tongue using ultrasound technology during his doctoral studies, and proceeded to collaborate with clarinetist Eric Hansen to write the book Extreme Clarinet, featuring very detailed descriptions of clarinet articulation technique including single and double tonguing.

In the included bibliography, notice that there are more early saxophone resources than early clarinet resources. This is especially interesting when one considers how much longer the clarinet has been around in comparison to the saxophone. Of course, a compiled list of multiple articulation resources for the flute would be considerably longer than both combined. Because of the lack of resources for clarinetists, the technique is often deemed “virtuosic.” This couldn’t be further from the truth. In fact, one thing all of these method books share in common is idea of approachability; no text states that this technique is only for the exceptionally gifted. Anyone can learn it.

Other Possible Techniques

With that being said, there may be limitations to the application of this form of multiple articulation, especially on the clarinet. As mentioned, when the tongue position becomes higher in the altissimo, the technique becomes exponentially more difficult, though still possible.

Luckily, there may be a solution. Largely unexplored, Keith Stein briefly mentions a sort of “paintbrush” form of multiple articulation in his 1958 book, The Art of Clarinet Playing. Forty years later, this was much elaborated upon by his student, David Pino, in his book The Clarinet and Clarinet Playing.

In 15 thorough pages, Pino outlines his grievances with the “off-the-reed” style of multiple articulation (as previously described, with the back of the tongue articulating on the soft palate) and shares his experience in discovering “on-the-reed” multiple articulation. In this style of multiple articulation, the tongue lightly brushes the reed tip, moving above and below the reed. To approximate the motion, Pino suggests pronouncing “tuttle.” This is another way to effectively solve the aforementioned movement-to-articulation ratio issue, as the tongue produces a note with each movement, both up and down. Pino asserts that the main challenge is actually slowing the tongue down and controlling the motion. Though it may be difficult at first, this method theoretically eliminates the voicing issues associated with off-the-reed multiple articulation, as it does not necessitate movement of the back of the tongue. Therefore, it should be possible in any range.

Unable to find more information on this interesting technique, I reached out to Juilliard professor Charles Neidich. He mentioned that this on-the-reed style of multiple articulation, and another style in which the tongue moves left to right over the reed, has a long history with Romani clarinetists, though it is admittedly not well documented. Neidich proceeded to advocate for a wider articulation palette in general, including all forms of double tonguing. He pointed to Johann Georg Heinrich Backofen’s 1802 clarinet treatise, which mentions a variety of possibilities for articulation using the tongue, lips or even the throat. During Backofen’s time, Neidich added, clarinetists were split between playing with the reed facing down on the mouthpiece as we do today, or flipped with the reed facing up. Backofen asserts in his treatise that he heard competent players using both methods, though Neidich mentioned that there was a difference in tone. Although today’s reed-down method produces more control in the tone, the reed-up method may have allowed for a more brilliant articulation. Many Italian clarinetists continued performing with the reed facing up well into the 20th century.

Looking Toward the Future

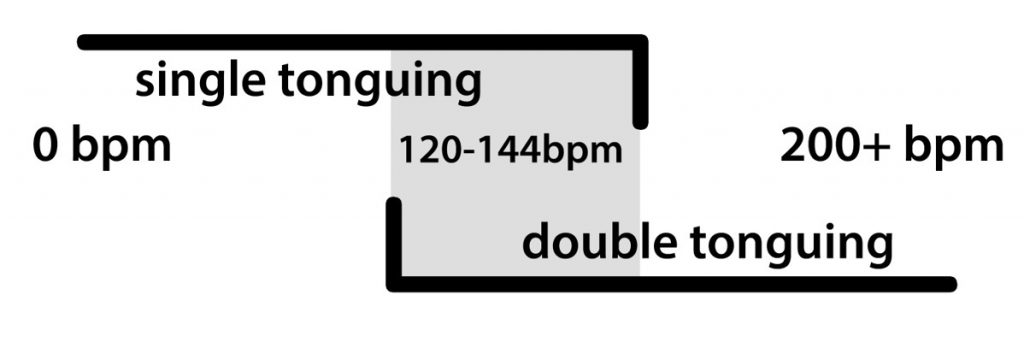

For clarinetists, opening up this dialogue is critical to our performance practice. String musicians have many options when it comes to articulation. Brass players and flutists also have several options, including a certain tempo range where they may choose to either single or double tongue, or alternate between the two. Clarinetists are often so limited by their single-tonguing that they choose to add slurs to certain excerpts in the repertoire. In certain passages where slurring is not a viable option, the ability of the clarinetist could even dictate the tempo of an entire orchestra, such as the Scherzo from Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Even in certain passages where slurring may be acceptable, there is no reason to limit options in articulation, a fundamental of musical performance. In fact, Michele Gingras notes in her book Clarinet Secrets that double tonguing on the clarinet matches well with other instruments that use the technique. Whether or not you plan to perform violin showpieces, fun as it may be, plenty of excerpts from the standard solo, chamber, and orchestral repertoire push beyond the limits of a well-trained single tongue.

In reviewing these materials and their authors, I hope I can renew interest in and access to these techniques and their respective histories, and help push clarinetists into a much-needed articulation renaissance. Sadly, many of the early materials mentioned are now out of print. Some are very difficult to find even through university interlibrary loan. As these old sources become frail, fewer libraries are inclined to circulate them. The time is now to memorialize these great materials, to learn from them, and to build upon them. And most of all, have fun with it!

A Compilation of Published Resources Regarding Multiple Articulation

(in chronological order)

Resources by Saxophonists

Eby, Walter M. Scientific Method for Saxophone: Saxophone Score. Boston: Walter Jacobs, 1922.

Cragun, J. Beach. The Business Saxophonist: A Course of Twenty Practical Lessons for the Business Player. Chicago: Rubank, 1923.

Weber, Henri. Sax Acrobatix: The Book of Saxophone Stunts & Tricks, Jazz Breaks, Jazz Endings and Altissimo Notes. New York: Belwin, 1926.

Wiedoeft, Rudy. Rudy Wiedoeft’s Secret of Staccato for the Saxophone. New York: Robbins Music, 1938.

Dorsey, Jimmy, and Jay Arnold. Saxophone Method: A School of Rhythmic Saxophone Playing. New York: Robbins Music Corp., 1940.

Douse, Kenneth. How to Double and Triple Staccato for Saxophone and Clarinet: A Revolutionary System of Rapid Tonguing. New York: M. Baron, 1948.

Teal, Larry. The Art of Saxophone Playing. U.S.: Summy-Birchard, 1963.

Compeán, Joe. Yes! Saxophonists Can Double Tongue. The Bandmasters Review, December 2007, 15-17.

Resources by Clarinetists

Backofen, Johann Georg Heinrich. Anweisung zur Klarinette nebst einer kurzer Abhandlung über das Bassett-Horn. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1803. Reprint, Celle: Moeck, 1986. Translation and Commentary by Susan Carol Kohler, 1997.

Christman, Arthur. Rebound Staccato. Woodwind Anthology (1952): 74-77.

Stein, Keith. The Art of Clarinet Playing. Princeton, NJ: Summy-Birchard Music, 1958.

Rehfeldt, Phillip. New Directions for Clarinet. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977.

Spring, Robert. “Multiple Articulation for the Clarinet.” The Clarinet (1989): 44-49.

Pino, David. The Clarinet and Clarinet Playing. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, Inc., 1998.

Gardner, Joshua Thomas. Ultrasonographic Investigation of Clarinet Multiple Articulation. Research paper, D.M.A.; Arizona State University, 2010.

Gardner, Joshua, and Eric Hansen. Extreme Clarinet. Louisville, KY: Potenza Music, 2012.

Gingras, Michele. Clarinet Secrets: 100 Performance Strategies for the Advanced Musician. Rowman & Littlefield, 2017.

Wolak, Kornel. Articulation Types: Clarinet. Toronto: Music Mind Inc, 2018.

About the Writer

Eric Schultz currently serves on the music faculty at Iona College, and as a teacher for the Harmony Program in New York City. He is an award-winning clarinetist, including the prestigious Rislov Foundation grant for excellence in classical music, and is the founding clarinetist of the Victory Players contemporary chamber ensemble of the Massachusetts International Festival of the Arts. Eric completed his Doctor of Musical Arts degree in clarinet performance at Stony Brook University. His principal teachers include Alan Kay, Alexander Fiterstein, and Melissa Koprowski. Eric will be giving a presentation regarding multiple articulation, including a short performance, on October 12 at the College Music Society National Conference in Vancouver, British Columbia.

Comments are closed.