Originally published in The Clarinet 48/4 (September 2021). Printed copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

The Pedagogical Legacy of Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr

by Jennifer Daffinee with contributions from Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr

2020 ICA Research Competition Winner

Dr. Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr

I first met Dr. Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr at the Oklahoma Clarinet Symposium in the summer of 2009, and I knew instantly that she was a force of nature. In our short master class she helped me find the confidence, color and interpretation I had not been able to draw out of myself (and she mentioned my left hand position needed work!). This encounter continues to inspire my own curiosity and learning to this day.

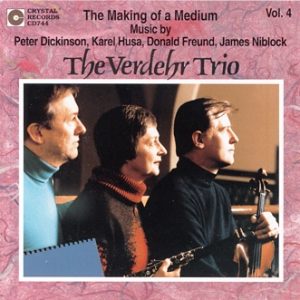

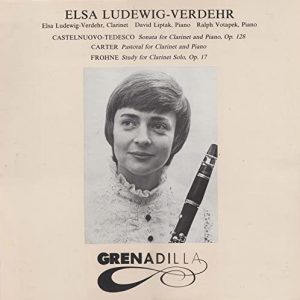

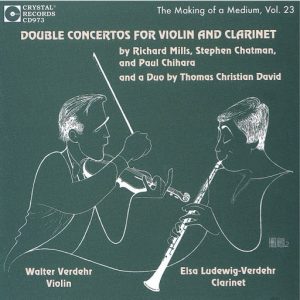

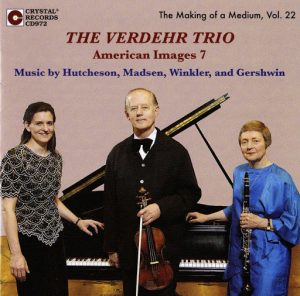

Her reputation speaks for itself: “an outstanding record of superior teaching skills of recognized breadth and depth in [her] discipline; scholarly, creative, and artistic achievements; and a distinguished record of public service; she is recognized internationally as one of the finest clarinetists in a field dominated by men; [she] is one of the most highly regarded and well-known clarinet pedagogues in the world today.”1 This description from Michigan State University’s Distinguished Professorship announcement in 1997 is as impressive today as it was 24 years ago. Verdehr officially retired from teaching in 2007, but remained on the MSU faculty as professor emeritus, coaching a limited number of students through 2018. She performed her last Verdehr Trio concert in 2015 and now she and her husband Walter Verdehr are cataloguing the trio’s materials and have completed three sets of nine additional Verdehr Trio CDs of works for violin, clarinet and piano, including four CDs of transcriptions (with printed music).

To current generations, she is regarded as one of the greats, a trailblazing legend in the industry, and as close to royalty as we might have in our clarinet community. However, to those who have not experienced her teaching or performance firsthand, her legacy may be unexplored. We know that without preserving the teaching methods of those such as Baermann, Klosé, Rose, Langenus, etc., their approach to clarinet study and performance would be lost. Their philosophies have been purposely recorded and preserved and their texts remain benchmark curricula throughout the world today. It is my bold contention that the methods of Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr be preserved alongside these writings.

I am excited to provide my 2020 ICA Research Competition findings from my 2018 dissertation, “Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr: American Clarinet Performer and Pedagogue.” Verdehr is completing a clarinet method book titled: The Verdehr Method – A Suggested Approach and Guide to Studying the Clarinet: Exercises for the Development of Tone, Technique, and Tonguing which contains original exercises, how to practice them and her thoughts about the physical nature of playing the clarinet. This article contains a sampling of the contents of the method book.

Literature Review

A review of the literature identified four articles, five biographical entries and one study which provide biographic details and reference Verdehr’s teaching practices; however, they do not capture the tenets of her methodology or specific pedagogical exercises. Although Dees’s research2 is the first to reference numerous handwritten exercises, they are not presented or analyzed.

Research Questions

Since these original pages only exist through circulated photocopies, the literature review and lack of public access to these materials demonstrate a gap in the research. This article seeks to answer: (1) What shaped Verdehr’s teaching? (2) What is her teaching philosophy? (3) What constitutes Verdehr’s methodology? and (4) What instructions does she provide?3

Example 1: Handwritten Exercises

Brief Biography

Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr was born on April 14, 1936, in Charlottesville, Virginia. Her first musical experiences were hearing the Saturday evening amateur string quartet rehearsals in which her father played.4 She began study of the clarinet in the fourth grade at 9 years old, and was exposed to a variety of teachers, musicians and conductors whom she credits with contributing to her musical outlook.

She speaks with gratitude about her high school band director, Sharon B. Hoose, as the earliest teacher to provide her the experience of playing symphonies and orchestral overtures. Hoose also conceived a regimented system of musicianship tests for developing individual skills: each of five progressive tests contained approximately 15 items covering topics such as scales, arpeggios, ear training, etudes and solo repertoire. Verdehr praises this system for developing her and fellow classmates “into musicians who were ready to move on to college and university music study.”5

During her sophomore year of high school she became enamored with the clarinet at Transylvania Music Camp, now Brevard Music Center, when she heard Ignatius “Iggy” Gennusa perform the Mozart Clarinet Concerto, K.622: “That was a revelation! I had no idea a clarinet could sound so beautiful and that was it. From then on I wanted to become a clarinetist!”6 She attended Oberlin College studying with George Waln, who Verdehr credits as “such a thorough and demanding teacher … He was just the right person for me at the right time and gave me a wonderful basic grounding on repertoire and technique.”7 During this study, she worked through many books: the Baermann and Mimart methods, Cavallini and Jeanjean etudes and others to which she would return through the years. She also covered much solo repertoire culminating in a memorized performance of the Nielsen Concerto, Op. 57, with orchestra her senior year.8 During Waln’s sabbatical her last semester she took lessons with Robert Marcellus of the Cleveland Orchestra who “opened me up to ideas of Daniel Bonade.”9

Verdehr attended the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York, for both her master’s and doctoral degrees. She dubs this period a “Golden Era of Eastman clarinet players” where she studied alongside legends such as Larry Combs, Peter Hadcock and Charles Bay. Her greatest influence at Eastman was Stanley Hasty, with whom she played second clarinet in the Rochester Philharmonic. His primary axiom of teaching would become the core of her philosophy: she stated, “basically he taught us to teach ourselves.” Deemed “too young” by Eastman to start her doctorate in 1959, she completed a second bachelor’s degree in music education from Oberlin and a Performer’s Certificate at Eastman. She then began D.M.A. study in 1960, while teaching at Ithaca College (1960-1962).

During his 1962 sabbatical she replaced Keith Stein at Michigan State University; he requested she stay on after his return. She finished her doctorate in 1964 and debuted at the University of Denver’s 1965 National Clarinet Clinic. Additionally, she spent four formative summers at the Marlboro Music Festival performing alongside renowned musicians Harold Wright, Marcel Moyse, John Mack, members of the Budapest Quartet, Rudolf Serkin and Murray Perahia. At MSU she became a member of the Richards Wind Quintet for 20 seasons, co-founded the Verdehr Trio (1972) with husband and fellow faculty violinist Walter Verdehr and performed in every U.S. state and 60 countries during their 43-year career, making 35 CDs and nine DVDs with the Trio. She achieved full professorship in 1976 and the Distinguished Faculty Award in 1979, while, in 1974, becoming principal clarinetist of the summer Grand Teton Festival Orchestra for 24 years. In 1997 she was appointed a Michigan State University Distinguished Professorship, retiring fully in 2018 after nearly 60 years of teaching. Additionally, her students have held collegiate teaching positions in 37 of the United States, Puerto Rico, and internationally in Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Mexico and Taiwan.

This is a prolific success rate and I offer that the global effects of Verdehr’s teachings are potentially unrivaled by any other American clarinetist of the 20th

century. In 2007 she received the ICA’s highest honor for lifetime achievement, the Honorary Member Award, for her distinction in the areas of professional service, teaching and performance.

Philosophy of Education

Verdehr’s systematic approach and philosophy are summarized by one key belief: “Teach students how to teach themselves.” She believes her techniques culminate into this one simple purpose: to be lifelong learners. She states, “I try to turn out thinking players who play musically.” As such, her ultimate teaching goal was to empower students

…not only to figure out and improve their technical way of playing, but also to be able to understand and perform a new piece of music based on what the composer wrote – to find what I call the hints, the suggestions, the harmonic implications, the phrases and sections and the character that the composer has put on the page for us to discover.10

As the consummate example of this philosophy, she never ceased re-examining her own approach and execution of playing, while learning new repertoire and commissioning more than 220 works for the Verdehr Trio. One such lecture was titled After Twelve Years,11 a presentation about how and why she re-thought and re-worked her approach to the clarinet – from hand position, finger usage, breathing and embouchure to more efficient ways of practicing.12

Verdehr also notes the influence of the Alexander Technique:

…the idea of not really correcting something one was doing incorrectly, so much as starting to do that something in a new and correct way. That is how it all came about really – the exercises to promote better hand position and the use of the fingers were exercises to instill new, correct and logical habits, similar to the concept of the Alexander Technique.13

Methodology

Example 2: Recurring Word Pictures

Verdehr’s methodology is her philosophy in action. After assessing each student’s background, her three-part approach encompassed addressing (1) the physical manner of playing, (2) how best to practice correctly, efficiently and effectively and (3) how to recognize and interpret a composer’s notation and intention to make music.14 This article focuses on the first tenet whereby she aimed for the most efficient way to improve holding the clarinet, using the fingers, and executing her exercises.

To augment individual lessons she held Monday night studio classes to discuss the technical aspects of playing the clarinet and to explain the exercises rather than repeating the same information in each private lesson; she also recommended that students work on these principles together in the practice room. This meant teacher and student could work more efficiently in regular lessons, focusing on repertoire and etudes (particularly Jeanjean etudes initially) while also working on topics covered in the previous Monday class. Her methodology also included well-planned sabbatical choices, bringing outstanding international clarinetists (e.g., Thea King, Kjell Stevenson, Luis Rossi) as well as national icons (e.g., Stanley Hasty, Larry Combs, Charles Neidich) to teach so her students would continue to develop during her Trio tours.

Former Student

Descriptive Survey

To investigate the effects of Verdehr’s philosophy and methodology, I conducted a survey of her former students examining their experiences. Participants were from either Ithaca College or Michigan State University between the years 1960 to 2007 who won professional performance and/or teaching jobs after studying with Verdehr. The survey gathered biographical data and asked six open-ended questions about the experiences, impact and value of studying with Verdehr. Thirty-five responses were received and independently organized. Participant names were removed to prevent researcher bias.

Data was organized by similar observation and/or theme and three broad categories were identified:

1 Participants’ perceived value of using Verdehr’s technical exercises

2 Verdehr’s instruction of musicianship

3 Accounts of Verdehr’s outlook on life, music, and the treatment of others

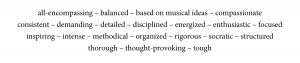

Thus, survey responses were classified into three value categories: technical, musical and experiential. Twenty-one recurring word-pictures were also identified as describing Verdehr’s teaching style (see Example 2).

Furthermore, an overwhelming 91% of participants cited Verdehr’s handwritten exercises as having the most impact on their ability to successfully play the instrument. The volume of participant responses which referenced these handwritten technical exercises caused me to further investigate: What are these exercises and how do they develop one’s performance ability?

Key Components to Ergonomic Hand Technique

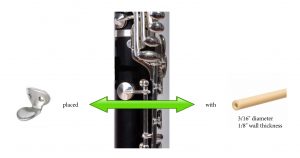

Example 3: Thumb Rest Setup

The effectiveness of Verdehr’s technical exercises is predicated on having the most ergonomic use of the fingers, hands, wrists and arms. About tension she adapted a quote from former Senator Everett Dirksen: “a billion here, a billion there – pretty soon you’re talking real money!” She warned: “a little tightness in the arms, a little in the wrists, a little in the palms of the hands and a little in the fingers – pretty soon you’re talking real tension!”

Verdehr feels the position of the right hand, specifically the right thumb which bears the weight of the instrument, is particularly important. To prevent side roll, decrease tension between the index finger and thumb and overcome the natural tendency to grip the right-hand rings while minimizing wrist and hand motion, she advocates a “wedge” right hand position: placing the weight of the clarinet on the right bone of the thumb joint, on the southeast corner of the thumb rest with the right side of the thumb nail pushing against the body of the clarinet. Thus, the clarinet balances itself firmly on the thumb at roughly a 30° angle to the body and the embouchure serves as the top balancing point creating a secure hold of the instrument. She likens the “wedge” to the image of sitting in a hammock: when one sits in a hammock it is difficult to get out; similarly when the clarinet is correctly wedged on the thumb it is difficult to dislodge and will not move from side to side. A full description of hand position is provided in the Verdehr Method Book.

Verdehr preferred the two-screw, non-adjustable thumb rests standard on most clarinets of the 20th century, while having also tried many other possibilities now available. She positioned the bottom of the thumb rest in line with the bottom of the sliver-key tone hole. She also added about an inch of rubber surgical tubing, pointed slightly to the left, over the thumb rest thus increasing the surface-area contact of the thumb. She calls it an “old fashioned but tried-and-true method!”

Because the left hand does not have a constant tactile reference like the thumb rest, the position of the left hand was based on where to position the fifth finger and the index finger for maximum comfort and use. She defined the home key for the left fifth finger as the “outside” F-sharp/C-sharp key because it slightly “shifted the hand position over toward the throat G-sharp/A-flat key making it easier to securely cover the ring-finger hole and open the F-sharp/C-sharp key.”

The other key attribute of her left hand position involved moving the left index finger directly two millimeters or so to the right, so that when using the throat G-sharp and A keys, one opens them directly on the joints of the index finger. She found this to be more effective because the knuckle joints have more strength and the remainder of the left hand falls nicely curved into place in this position.

Verdehr feels that the fingers and the clarinet are diabolically engineered to encourage unevenness because each spring has a different tension and each finger has a different skill and speed. To combat that, the idea of using an equal and definite amount of finger action to lift and lower the fingers to prevent unevenness, or “up equals down,” was a mindset she learned from Rosario Mazzeo (longtime bass clarinetist of the Boston Symphony Orchestra). She identifies two types of finger motion: for technical fingers, envision a gentle pop, snap, relaxed fling or drop of the finger in the curved position, moving from the “back knuckle.” The finger remains unbending – think of a fishing pole that lifts and lowers, with an imaginary “fishing line” extending from the tip of the finger through the center of the tone hole. Move each finger only about an inch above the tone holes, keeping the pad (not the tip) of the finger pointed downward. For legato fingers, the opposite resistance is imagined. Still curved and moving from the back knuckle, envision that each tone hole has a ballpoint pen spring inside it sticking out above the hole. Imagining the resistance of pushing the spring into the instrument, one moves the finger rather slowly down to the tone hole. When the motion is reversed the finger lifts as if releasing the spring slowly, not allowing it to “fly out.” The fingers may extend two or three inches, still curved, above the tone holes to help achieve a descent that minimizes the sound of the finger(s) meeting the tone holes. This applies to fifth-finger keys and the other levers as well.

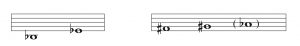

A somewhat unique use of each index finger occurs in what Verdehr labels the “problem areas” – areas where excess wrist action can occur (see Example 4). Moving back and forth between low B-flat and side E-flat is one “problem area;” moving between throat F-sharp and G-sharp (A-flat) is another.

Example 4: Problem Areas

Example 5: Problem Areas continued

To open the key for these motions, the index finger should unbend and straighten from the “middle knuckle” and curve back to close the key. This should be largely finger motion with only a small wrist motion. This is also the basic movement involved, with the addition of other fingers, when negotiating many other intervals (see Example 5).

The Verdehr Method

Verdehr’s handwritten pages have been analyzed and reviewed, organizing content into three categories: tonal, technical and articulation studies, with corresponding practice technique guides. This new book is titled The Verdehr Method – A Suggested Approach and Guide to Studying the Clarinet: Exercises for the Development of Tone, Technique, and Tonguing. Again, she aims to produce “thinking players” and feels that to go through these exercises without understanding how to practice them would be mindless repetition. She emphasizes that these exercises are not intended to be completed quickly; rather, like other method books (Baermann Clarinet Method, Book 3; Rudolf Jettel Klarinette Schule, Book 2) the Verdehr Method Book is a months/years-long project, each person steadily progressing at their own pace. Also, one may choose to revisit the exercises at a later time (months or even years later) and/or perhaps adopt some of the exercises as part of a daily warmup routine. The following is an explanation of the key material in each area.

Tonal Development

The exercises for tonal development each begin with a deep full breath, as indicated by the breath mark above the open first measure. The purpose of the exercise is to establish a rich, resonant tone on low E and match the sound in color and volume as one ascends, conceptualizing a fast-moving, dense air stream. Then at the end of the exercise, another breath is taken – a “reflex” breath reflecting tenets of the Alexander Technique, which is fully explained in the book. Note that the exercise is not written out in every key. This is an intentional and necessary aspect of the entire method – each exercise is designed for transposition through the ranges specified. In this case, after a few days of playing the original exercise, the exercise could be transposed to low F, and after a few more days to F-sharp and so on (see Example 6).

To begin the Chromatic Tonal Exercise, Verdehr recommends first playing a rich, full low G. Then add the register key with no change to air stream, embouchure or dynamic, so that the player hears and “feels” the ring and richness of the sound of the clarion D. Upon experiencing the “ring” of the upper tone, the player should apply that concept to the notes in the clarion register of the exercise, again taking the “reflex” breath at the top of the exercise.

Further tone exercises deal with intervals. As Stanley Hasty would say, “Anyone can make a good sound, but can they play a good interval?” The Revised Abato Exercise introduces wider intervals and legato fingers, in which low E is the principal key-note while the second note is a changing note. Thus, for the first exercise one plays low E to low F through the range of the exercise, thereby practicing the intervals of a minor 2nd and a major 7th, etc. For a second exercise, the second note is changed to low F-sharp (while the key-note remains low E) and the intervals change to a major 2nd and minor 7th. Similarly, for a third exercise, the second note is changed to low G (while the key-note remains E), the intervals become a minor 3rd and major 6th, and so on with each changing note.

Verdehr used the Revised Moyse Exercise at times to target “the break” or the first register change, but one can also transpose the exercise beginning on any note from low E to clarion G as an exercise to match tone in all registers.

Example 6: Tone Exercises

Technical Development

Elsa and Walter Verdehr

Preliminary Exercises

The exercises in Example 7 work the correct movement of each finger alone and in combinations – first one finger, then two fingers together, then three and finally four. Importantly, in No. I and II while maintaining correct position and finger usage (explained in depth in the book), one begins each exercise very slowly and gradually increases the speed to a medium tempo, keeping the palm of the hand relaxed and without tension. As time goes on, the speed will become faster while the palm and arm should still remain relaxed. In the book Verdehr also uniquely identifies “problem areas” involving both index fingers as well as the fifth fingers with specific suggestions and exercises for these.

Example 7: Preliminary Exercises

Scale Exercises

The technical exercises are designed to begin with the most basic patterns or units of scales and arpeggios and gradually increase their scope and range (see Example 8). A basic premise throughout the book when practicing these technical exercises is to first concentrate on a few notes, played slowly using correct finger motion with correct wrist and hand position. Gradually over time one increases the number of notes, range and speed of each exercise. Various exercises were developed to facilitate learning scales evenly and rapidly without tension.

Scale Segments were originally developed to focus on the evenness and action of the fourth or “ring” finger. This was the first exercise created and the principles from it evolved into the many other exercises. In line 1 an additional sharp is added to each bottom set of notes, thus creating a similar, but new exercise. The notes in parentheses represent the segments of scales a twelfth higher which, from a fingering standpoint, are basically also being practiced although one is actually playing only the lower notes. The sharps represent the keys being practiced in the lower (and upper twelfth) register. Lines 2 and 3 each represent a repetition of the principles of line 1 except that line 2 is set a fourth higher, and line 3 an octave higher. Like most every Verdehr technical exercise, one begins slowly and gradually accelerates to a medium or medium-fast speed concentrating on evenness and relaxation. Scale segments should also be practiced in flat key signatures.

A second exercise for practicing scales is Scale Fragments. One plays the first three notes of the scale, beginning in the key of each note of the chalumeau register. First one practices three notes on each scale degree; then four notes, then five, etc., again beginning slowly and gradually accelerating. This provides a slightly different way of practicing each scale as do Scale Parts and One-Way Scale Bits.

Example 8: Scale Exercises

Arpeggio Exercises

Arpeggio exercises and other basic exercises were developed to be practiced using the same principles outlined for scale exercises (see Example 9).

The Verdehr Method includes many additional exercises not covered in this brief summary, as well as detailed explanations and suggestions for practicing and understanding the logic behind the exercises.

Example 9: Arpeggio Exercises

Additional Findings and Further Research

This study unexpectedly yielded a biographical index of 95 former students including performers, teachers, orchestral conductors and academic administrators. Because this research focuses exclusively on physical performance, the second tenet (how best to practice correctly, efficiently and effectively) and third tenet (how to recognize and interpret a composer’s notation and intention in order to make music) of Verdehr’s methodology provide opportunity for future research.

Example 10: Right Thumb Wedge

Conclusion

Finally, I return to the idea that Verdehr aimed to create “thinking players.” This is a brief summary of selected contents in her upcoming book that demonstrate how Verdehr worked towards that goal. The method also includes scale parts, one-way scale bits, scales in thirds, triplet scales, chromatic fragments, chromatic triplets, legato fingers and articulation exercises. The book provides opportunity for clarinetists to evaluate their approach, read her explanations, apply them to her exercises and be their own systematic problem-solving detectives: identify a problem, find the solution for it and create exercises to overcome the problem. This was the genesis of the book. Therefore, I offer that The Verdehr Method merits attention and preservation for current and future generations who wish to experience the wisdom and logic of her approach.

Elsa Verdehr and Jennifer Daffinee are working toward publication of The Verdehr Method for 2022.

Endnotes

1 “Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr Awarded University Distinguished Professorship,” Michigan State University Announcement, 1997.

2 Margaret Iris Dees, “A Review of Eight University Clarinet Studios: An Investigation of Pedagogical Style, Content and Philosophy through Observations and Interviews” (D. M. diss., Florida State University, 2005), 90-103.

3 The research presented herein was obtained through Internal Review Board approved written and in-person interviews, email correspondence, and open-ended surveys of former students.

4 Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr, email to Jennifer Daffinee, March 8, 2016.

5 Ibid.

6 Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr, “Interview with Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr,” Interview by Jennifer Daffinee (East Lansing, MI: November 20, 2016), 96.

7 Ludewig-Verdehr, email, March 8, 2016.

8 Ludewig-Verdehr, “Interview,” 22.

9 Ibid, 155.

10 Ibid, 3.

11 Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr, Lecture (n.d.), Denver, CO.

12 Ludewig-Verdehr, “Interview,” 18.

13 Ibid, 41.

14 Ibid, 23, 27.

About the Writer

Technical Sergeant Jennifer Mendez Daffinee is a member of the United States Air Force Band of the West stationed in San Antonio, Texas. In 2020 she won first prize in the ICA Research Competition. Dr. Daffinee studied with Ron Scott (Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi), Mary Alice Druhan (Texas A&M University-Commerce), and James Gillespie & Kimberly Luevano (University of North Texas).

Comments are closed.