Originally published in The Clarinet 46/3 (June 2019). Printed copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

The Bohlen-Pierce Clarinet: Exploring a New Tonality

by Nora-Louise Müller

Left to right: BP soprano, contra and tenor clarinet (Photo by Nora L. Müller)

Bohlen-Pierce clarinets have been enriching contemporary music since 2008. The overwhelming effect of the Bohlen-Pierce (BP) scale can hardly be described in words. It is the immediate aural impression that opens the doors to this alternate tonal world. Unlike the scales of our usual system, it is not the octave that forms the repeating frame but the perfect twelfth (octave plus fifth; in BP terms a “tritave”), dividing it into 13 equal steps according to various mathematical considerations. Each step is almost equal to a three-quarter tone in equal temperament: 146.3 cents. Simplified, one can imagine this as an elastic band: instead of reaching the octave after 12 semi-tone steps we stretch the elastic band in order to choose the tritave as the returning point. We hence go about one and a half times as far as before, with only one step more. Thus, an alternative harmonic system evolves in which, notably, the octave does not appear. Due to the step size that differs from the usual, the octave is simply stepped over.

Consequently, chord structures evolve that are acoustically different from the ones we are used to. For example, in our usual tone system the notes of a major chord have the frequency ratio 4:5:6. If the BP scale can be seen as a scale “stretched” in comparison to the standard octave-based system, it makes sense to stretch its main triad as well. The result is a chord with a frequency ratio of 3:5:7, generating a completely different but harmonic chord.1 The different step size of the scale results in many intervals and harmonies which are nonexistent in the traditional 12-tone scale. These novel, yet harmonic triads are the basis of a new musical horizon in which the BP clarinet plays an important role.

The Bohlen-Pierce Scale

The Bohlen-Pierce scale is named after two illustrious people who found the scale independently of each other. In the early 1970s, German microwave electronics and communications engineer Heinz Bohlen (1935-2016) was looking for an answer to a question that none of his composer and music theorist friends could answer satisfactorily: Why is our musical system made of an octave divided into twelve steps? He found one of the reasons in our auditory system. Combination tones, it seemed to him, play a major role in our preference for the major triad. Once he understood the basics of music perception, he was able to modify numbers and frequency ratios and thus came to his scale of 13 steps within the perfect twelfth.2

In the mid 1980s the scale was discovered again, this time by American engineer John R. Pierce (1910-2002). Interestingly enough, he had exactly the same profession as Bohlen, working for decades in satellite technology. Pierce developed a number of items that are still used in satellites today. Only after his retirement did the passionate amateur musicologist take up a position at the Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) at Stanford University in California. His colleague Max Mathews, a pioneer of computer music, had synthesized the 3:5:7 triad on the computer for an experiment on intonation perception. Later on, he and Pierce wondered what scale would accommodate this special triad. As they found no suitable octave division, Pierce had a flash of insight and chose the perfect twelfth as harmonic frame for the scale.3 It was Pierce who named this interval a tritave, due to its frequency ratio of 3:1, in contrast to the octave’s ratio of 2:1.

Creation of the BP Clarinet

At the time of its discovery in the 1970s, hardly any acoustic instruments playing the scale were at hand. If so, they would have been homemade experimental instruments rather than instruments fulfilling professional standards. Synthesizers were out of the financial reach of most people. Due to the lack of instruments, the scale fell more or less into oblivion for many years after its discovery – until woodwind maker Stephen Fox (Toronto) created a BP clarinet,4 a project instigated by Georg Hajdu, professor of multimedia composition at Hamburg University of Music and Theatre (HfMT Hamburg) in Germany. Hajdu had been a passionate advocate of the scale for many years and felt the urgent need for BP clarinets. He had realized that the clarinet would be the perfect instrument to play the BP scale since, by overblowing to the perfect twelfth, it naturally offers the new scale’s harmonic frame.5

BP soprano clarinet; this specimen has

two extra keys on the upper joint (G-sharp and E-flat) which do not give BP pitches but rather some flexibility regarding color fingerings, multiphonics or microtonal trills (Photo by Detlev Müller)

Detail of upper joint of BP soprano clarinet with two extra keys Photo by Detlev Müller

Fox’s creation, the BP soprano clarinet, is of the same length as a normal B-flat clarinet and shares the tuning note A (clarion B). Consequently, the sounding low D (finger position of low E) matches the standard twelve-tone system as well. The BP pitches within this tritave are achieved by “chromatic” keywork such as the pinky keys for low E/G-sharp, followed by open tone holes (chalumeau G, A, B-flat, C, D, E, F, G, to give a comparison with a standard clarinet) and an “A key.”

Initially, Fox made four of these clarinets. The first pair he kept for himself and his colleague Tilly Kooyman. The second pair was shipped to Hamburg and handed to Lübeck clarinetists Anna Bardeli and myself, Nora-Louise Müller. Teams of musicians and composers gathered for the project, and in 2008 the BP clarinets were premiered in two different concerts by teams in Guelph, Canada, and Hamburg, Germany.

In 2010 the Hamburg team commissioned a BP tenor clarinet from Fox, sounding six BP steps (a conventional major sixth) lower than the BP soprano. Fox gave it the look of an alto clarinet with a metal neck and bell.

The latest addition to the BP clarinet family was unveiled during ClarinetFest® 2018 in Ostend: a BP contra-clarinet, sounding a tritave (or perfect twelfth) lower than the BP soprano and thus of the size of a contra-alto clarinet. Thanks to government funding through the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, HfMT Hamburg was able to commission this brand-new and innovative instrument for the 10th anniversary of the BP clarinet project.

Repertoire for the BP Clarinet

Ten years after the premiere, the European side of the project is still thriving, and collaborations with musicians and composers from the Netherlands, Belgium and Estonia are set up as often as possible.

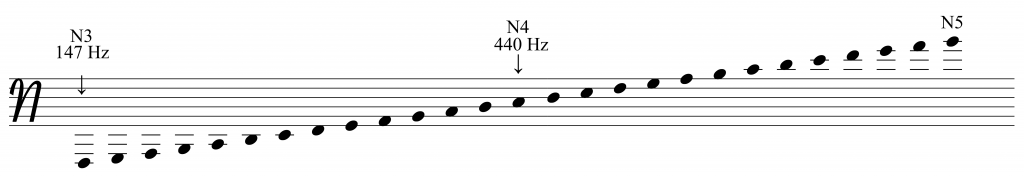

Figure 1: Notation of the BP scale in N-clef

The repertoire has been growing constantly and shows a broad horizon of approaches. Composers who wrote works featuring BP clarinets include Manfred Stahnke (Germany), Clarence Barlow (U.S.), Todd Harrop (Canada), Georg Hajdu (Germany), Julia Werntz (U.S.) and Gayle Young (Canada). Some of the three-dozen compositions to date make use of the particular harmonic world of BP which may be perceived as “stretched”; other composers combine a BP clarinet with a traditional clarinet, either to offer subtle nuances in melodic developments, or to generate a cosmos of microtonal pitches and scales; yet other composers approach the pitch material from their experience with the Indian raga system, resulting in intertwining melodies based on long bordun intervals. Ancient forms such as passacaglia come to new life by the use of electric guitar, also tuned to BP, in combination with clarinet and viola. Solo pieces can be found in the repertoire as well as BP clarinet trios; pieces employing live electronics; unusual combinations of instruments or bigger ensembles of acoustic, electric and electronic instruments.

Notation for the BP Clarinet

In the beginning of the project, compositions were notated in a clarinet-specific fingering notation which allows the clarinetist to read and play from a conventional notation. Although comfortable for the clarinetist, it turned out to be problematic especially in ensemble settings, because it does not in any respect represent the actual sound. Traditional notation on five lines, using microtonal accidentals, is also problematic as it, too, cannot display the inherent logic of the BP scale. Therefore, a specific BP notation on six lines has been developed by Müller and Hajdu (see Figure 1).6

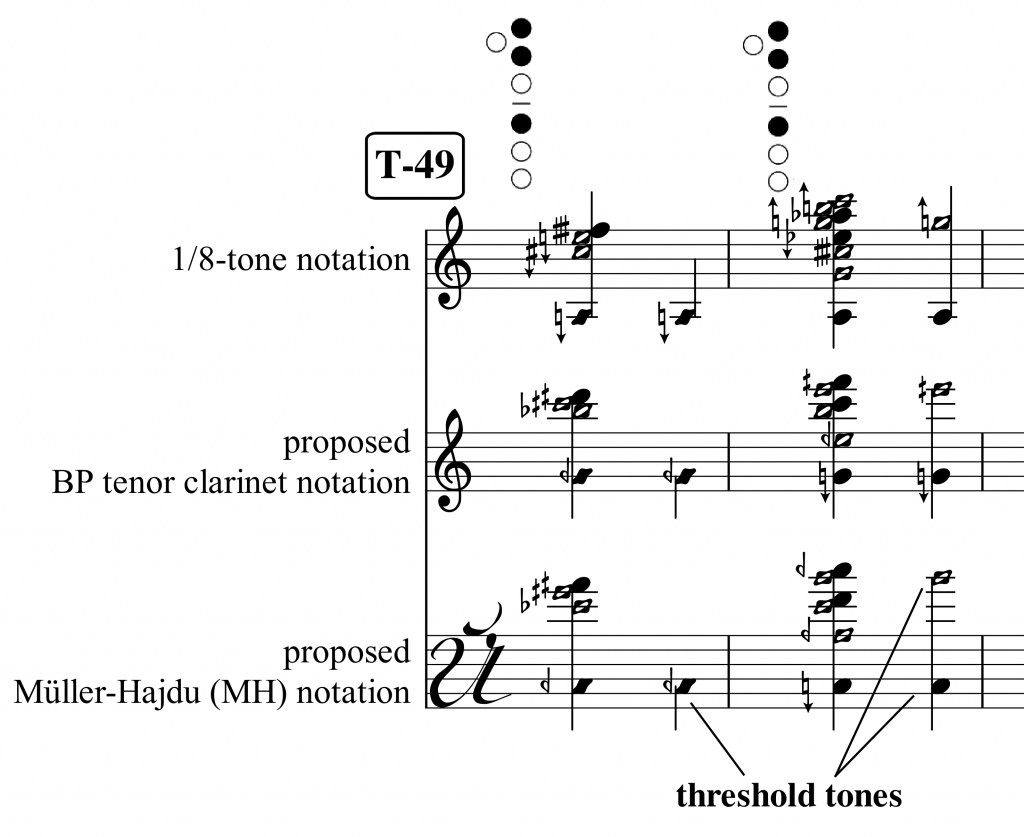

Figure 2: Multiphonics for BP tenor clarinet in three different notation systems: concert pitch, clarinet

fingering notation and BP notation (U-clef for BP tenor clarinet)

To avoid confusion with the standard 12-tone system, pitches have been named according to the last 13 letters of the alphabet, N-Z. As mentioned before, the BP clarinet is anchored with the common tuning note A of the traditional system which is situated in the middle of the six-line staff. This same note is named N4 in the BP system and is played as a clarion B.7 The note a tritave below, the fingered low E, is named N3; the tritave above is called N5. Accidentals are not needed. To indicate the reference note N4, an N-clef is used.

For the BP tenor clarinet, a U-clef has proven successful by allowing the clarinetist to connect the same fingerings with notehead positions in the staff as with the BP soprano clarinet (i.e. U3 on a BP tenor clarinet is shown in the middle of the staff, indicated by a U-clef and played like a clarion B). The BP contra clarinet can use the N-clef, sounding a tritave lower than notated. This notation has been designed from a clarinetist’s point of view and perfectly fits the needs of clarinetists; however, it also proved convenient for other instruments and is currently used not only by BP clarinetists but also by composers, string players and guitarists.

Possibilities of the BP System

To give composers and clarinetists helpful material, ongoing research about playing techniques is documenting practical differences between BP and standard clarinets with regard to aspects such as high-register playing and glissandi. Tone holes on the BP clarinet have been located to match pitches of the BP scale, while keywork is relatively simple.8 Consequently, multiphonic fingerings have given results specific to BP clarinets. A number of BP clarinet multiphonics for BP soprano and tenor clarinets have been found and analyzed by use of specialized software.9 The sounds have been transcribed into three different notations: concert pitch using eighth-tone accidentals to give the closest possible approximation of the sound in standard notation; BP fingering notation as preferred by clarinetists who are not (yet) familiar with BP notation on six lines; and notation in N- or U-clef using microtonal accidentals to give an approximate representation in the six-line notation. Furthermore, threshold notes are indicated as suggested by authors such as Weiss/Netti10 and Mahnkopf/Veale.11 A multiphonic can be “snuck” into by starting on a (monophonic) threshold note before opening up into the full multiphonic sound. In Figure 2, threshold notes are the ones at the end of each bar.12

BP music provides new aesthetic horizons for contemporary music. What strikes us most about BP music is the possibility of finding completely new soundscapes and aural experiences within an alternative tuning system. Our experience so far is that, on one hand, audiences find it intellectually provoking to think of a tonal system that avoids the octave,13 and, on the other hand, they find it inspiring and stimulating to listen to BP music as it is often perceived as a kind of “otherworldly music.” Through its characteristically new and unfamiliar yet harmonic system, BP music has the potential to enrich contemporary music as composers, performers and audiences continue to explore the possibilities of this new tonality.

* * * * *

A CD featuring music for BP clarinets is currently in preparation. Until then, some examples of BP clarinet music can be found at www.tinyurl.com/bpclarinet.

List of Works Featuring BP Clarinets

BP clarinet solo, with or without electronics

James Bergin, Liebesleid (2010) for BP clarinet solo

Todd Harrop, Zaubersephir (2011) for BP tenor clarinet and electronics

Todd Harrop, Bird of Janus (2012) for BP clarinet solo

Peter Köszeghy, Utopie XVII (chochma) (2009) for BP clarinet and fixed audio

Katarina Miljkovic, For Amy (2010) for BP clarinet and electronics

Nora-Louise Müller, Lady Low Delay (2019) for BP contra clarinet and delay

Anthony de Ritis, Five Moods (2010) for BP clarinet and tape

Julia Werntz, Imperfections (2010) for BP clarinet solo

BP clarinet duos, with or without electronics

Owen Bloomfield, Wanderer (2008) for two BP clarinets

Peter Köszeghy, Sedna (2011) for BP clarinet, BP tenor clarinet and fixed audio

Johannes Kretz, Hoquetus II (2010) for two BP clarinets and live electronics

Manfred Stahnke, Die Vogelmenschen von St. Kilda / The Bird People of St Kilda (2007) for two BP clarinets

Arash Waters, Little Duet (2011) for two BP clarinets

Duos for BP clarinet and traditional clarinet, with or without electronics

Roger Feria, RE: Stinky Tofu (2010) for bass clarinet and BP clarinet

Sascha Lino Lemke, Pas de deux (2008) for B-flat clarinet, BP clarinet and live electronics

Fredrik Schwenk, Night Hawks (2007) for B-flat clarinet and BP clarinet

Frank Zabel, Sie sind zu lange im Wald geblieben (2011) for bass clarinet and BP tenor clarinet

BP clarinet trios

Ákos Hoffmann, Duo Dez (2015) for two BP soprano clarinets and BP tenor clarinet

Nora-Louise Müller, Morpheus (2015) for two BP soprano clarinets and BP tenor clarinet

BP clarinet quartets

Clarence Barlow, Pinball Play (2010) for four BP clarinets

Chamber music and ensemble works including BP clarinets

Owen Bloomfield, When the Ravens Descend (2010) for soprano voice, BP clarinet and BP tenor clarinet

Jim Dalton, Contemplating Duality (2013) for BP clarinet and marimba

Emily Doolittle, Body of Wood (2010) for soprano, BP clarinet, cello and percussion

Georg Hajdu, Beyond the Horizon (2007) for two BP clarinets and synthesizer in BP

Georg Hajdu, Burning Petrol (2015), an arrangement for BP ensemble after Alexander Scriabin’s Vers la flamme, for two BP soprano clarinets, BP tenor clarinet, electric guitar, synthesizer, double bass and percussion (tam-tam, kalimba; one player)

Peter Michael Hamel, Die Umkehrung der Mitte (2007) for two BP clarinets, viola, marimbaphone & vibraphone (one player)

Peter Hannan, No brighter sun – no darker night (2009) for soprano, two BP clarinets, cello (BP) and malletKAT (BP)

Todd Harrop, Calypso (2008) for two BP clarinets, percussion (hand drums, BP chimes) and fixed audio

Todd Harrop, Maelström (2015) for BP clarinet, BP tenor clarinet and electric guitar (BP)

Benjamin Helmer, Preludio e Passacaglia (2015) for BP tenor clarinet, viola, electric guitar and kalimba (all in BP)

Neele Hülcker, Dumosus (2010) for oboe, BP clarinet, BP tenor clarinet and double bass

Christian Klinkenberg, The Leaves that Hung but Never Grew (2018) for BP ensemble (clarinet, electric guitar, electric bass, violin, chimes, two drumsets) and storyteller

Christian Klinkenberg, The Glacier (2019) a microtonal opera including BP clarinets

Hans-Gunter Lock, Kolm fragmenti (Three Fragments) (2014) for BP clarinet, BP alto recorder and BP piano

Hans-Gunter Lock, NN (2019) for BP contra clarinet and live electronics

Stratis Minakakis, Anacharsis I (2010) for BP clarinet, violin and percussion (dumbek)

Jasha Narveson, Wire (2010) for two BP clarinets and BP percussion

Manfred Stahnke, Just Intonation in Bohlen-Pierce – ein klingender Essay (2015) for BP tenor clarinet and viola in just 7/3 tuning

Gayle Young, Cross Current (2010) for two BP clarinets, BP recorder, amaranth, percussion

Endnotes

1 Intervals of simple frequency ratios are perceived as consonant; see Hermann von Helmholtz, Die Lehre von den Tonempfindungen als physiologische Grundlage für die Theorie der Musik., (Braunschweig, 1863); James Tenney, A History of Consonance and Dissonance, (Excelsior, 1988).

2 Heinz Bohlen, Versuch über den Aufbau eines tonalen Systems auf der Basis einer 13-stufigen Skala, (manuscript, 1972); Heinz Bohlen, 13 Tonstufen in der Duodezime, Acustica, 39(2):76-86, 1978.

3 Max V. Mathews, John R. Pierce, L.A. Roberts, Harmony and New Scales, in: Harmony and Tonality, (Stockholm, Royal Swedish Academy of Music, 1987), 54:59–84.

4 www.sfoxclarinets.com/bpclar.html.

5 It is not possible to play music in BP tuning on a conventional clarinet. The different step size of the BP scale creates pitches which seldom match those of the twelve-tone scale and thus would generate severe difficulties in finding suitable fingerings when played on a conventional clarinet. Intonation, sound quality and the player’s virtuosity would suffer to such a great amount that listening to and playing music in BP tuning on a conventional clarinet would not be very enjoyable.

6 Notation on more than five lines has been suggested in other contexts by Josef M. Hauer and others; see Thomas S. Reed, Directory of Music Notation Proposals, (Notation Research Press, Kirksville 1997).

7 The note name N4 has been chosen in accordance to scientific pitch notation which describes A=440Hz as A4.

8 Stephen Fox, “The Bohlen Pierce Clarinet”; lecture during BP conference in Boston, Massachusetts, March 2010.

9 SPEAR by M. Klingbeil, www.klingbeil.com/spear, in combination with Macaque by G. Hajdu, http://georghajdu.de/6-2/macaque.

10 Marcus Weiss and Giorgio Netti, The Techniques of Saxophone Playing (Bärenreiter, 2010).

11 Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf and Peter Veale, The Techniques of Oboe Playing (Bärenreiter, 2001).

12 A warm thank-you to Bret Pimentel for providing his brilliant fingering diagram builder at www.bretpimentel.com.

13 Suggested further reading: William A. Sethares, Tuning, Timbre, Spectrum, Scale (Springer, 2005), 110-112.

About the Writer

Nora-Louise Müller is an avid interpreter and improviser and regularly performs in festivals such as Microfest (Amsterdam), festival (DA)(NE)S (Maribor, Slovenia), klub katarakt (Hamburg) and Chiffren – Kieler tage für neue musik. As one of the very few clarinetists worldwide who perform on Bohlen-Pierce clarinets, she has also spoken on alternative tunings at various international music conferences. In 2018, she was awarded second prize in the ICA Research Competition for this research, and her Ph.D. thesis, “The Bohlen-Pierce Clarinet – A Practical Guide to Performing and Composing” will be published in 2019. She lives in Lübeck, North Germany and is a sessional lecturer at HfMT Hamburg.

Comments are closed.