Originally published in The Clarinet 46/4 (September 2019). Printed copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

Mozart had his Anton Stadler

Bartók and Copland their Benny Goodman

and Previn his Tom Martin

by Bruce M. Creditor

André Previn was the ultimate musician: classical and jazz pianist, composer, arranger, conductor, music director of four orchestras, recipient of numerous Academy and Grammy awards, television star, raconteur and author. He passed away on February 28, 2019, and the many obituaries, tributes and online articles highlighted these facets of his unique career, including his opera A Streetcar Named Desire. It is his catalog of concert music including works for large orchestra (check out his Honey and Rue) and chamber music ensembles that bring me to spotlight his wonderful two works for clarinet.

Tom Martin performing with André Previn at the piano

I am indebted to clarinetist Tom Martin for sharing various aspects about his early career, his involvement with André Previn and the two works written for him. This is about much more than just those works, but also about the development and evolution of a career – the various persons, experiences and luck of place and time.

Tom is associate principal clarinet of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, principal clarinet of the Boston Pops Orchestra and faculty at the New England Conservatory of Music. A graduate of the Eastman School of Music, where he was a student of Stanley Hasty, Tom has worked with most of the world’s leading conductors, soloists and entertainers and maintains an active schedule as a soloist, chamber musician and teacher. In addition to two works by Previn, he has given premieres of chamber works by several composers including Elliott Carter and noted Czech composer Miroslav Srnka. Unusually adept at straddling both worlds of classical and jazz, his numerous and highly acclaimed solo performances with the Boston Pops include a nationally televised performance of the Artie Shaw Clarinet Concerto on “Evening at Pops,” and a 100th anniversary tribute to Benny Goodman which was performed in Boston’s Symphony Hall, the Tanglewood Music Festival and New York’s Carnegie Hall.

Bruce Creditor: Prior to the classical training you received from Stanley Hasty at Eastman, who were your early influences and mentors?

Tom Martin: I grew up watching the Boston Symphony and the Boston Pops on their respective PBS television programs. It’s a little shocking to me to think now that when I was 11 I loved both the music of the big band era and orchestral music so much that I had decided the only place I could do both was to be the principal clarinetist of the Boston Pops. I tell my students to be careful what they wish for because it might come true!

I was fortunate to grow up in a town that had a wonderful school music program and public library. The Oshkosh (Wisconsin) Public Library had a treasure trove of recordings and musical scores to peruse. There was also a wonderful program on Wisconsin Public Radio called “Jazz Classics” which was hosted by Ken Ohst. It was from Mr. Ohst’s program that I was introduced to jazz from its beginnings to the late swing era. I got to hear recordings of all the great clarinetists from the early beginnings of recorded jazz.

My middle school band director, Robert Boisen, was my first clarinet teacher. He also taught me music composition and introduced me to the great works of orchestral music and jazz. This continued in high school with my band director, Peter Schmalz. He also taught music history and theory to any of us that wanted to learn.

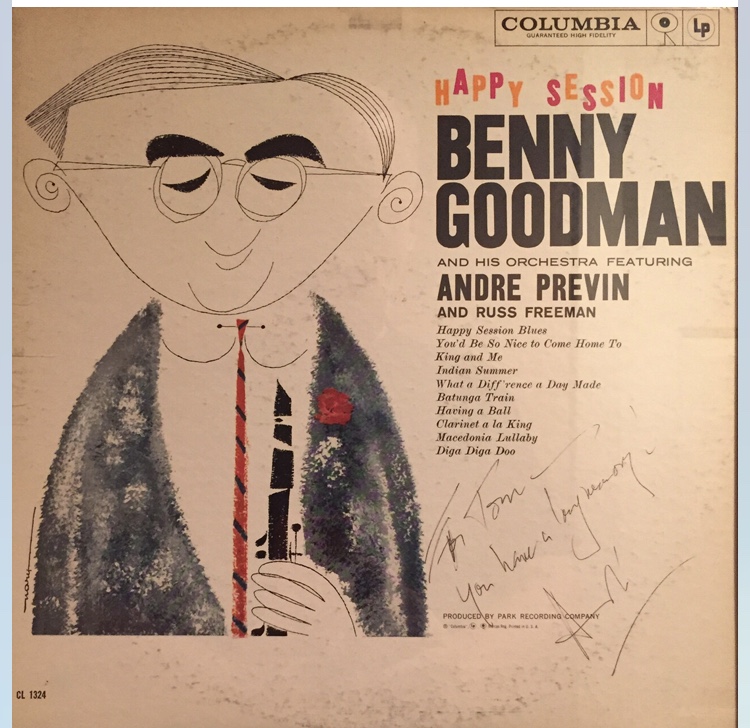

It was also at this time that I was watching a wonderful program on the television: “Previn and the Pittsburgh.” Such a great program! André Previn was a musician that I first heard on an album of Benny Goodman’s called Happy Session. There is a tune on it called “King and Me” written, arranged and performed by Mr. Previn. It was so exciting to watch the program … to see and hear the orchestra and know that the brilliant conductor of the orchestra was also a brilliant composer, pianist and jazz musician!

When I was 13 a friend of our family introduced me to a jazz saxophonist from the area. He came to my home with his tenor saxophone and asked me to play some songs with him. A mini-jam session, I suppose. After a few tunes, he asked me to sit in with his combo for a set at the club they were playing at that weekend. My parents and the friend of the family that introduced me to this saxophonist all came to the club to hear me play. Afterward, a gentleman approached me and asked how old I was. He gave my father his business card and left. A few weeks later he called on the telephone and asked if I could join his big band. A few weeks after that I got a call from another band leader in town asking if I could be the reed player in his trio. My father drove me to the local musicians’ union and I joined. At one point I was playing in two big bands and one trio… oh… and going to school too! It was in the trio that I eventually began to play the flute. But my flute playing was always a very weak third to my clarinet and saxophone. I’d have to warm up with long tones for an hour before I could get even a sound – acceptable or not

Cover of Benny Goodman’s Happy Session, inscribed to Tom Martin from André Previn

Benny Goodman was the first jazz clarinet sound I ever heard. By the time I listened to “King and Me” I had already transcribed many of his solos from the 1930s big band, trio and quartet recordings. The Happy Session album is a leaner clarinet tone compared to what Goodman was sounding like in the heyday of the big band era. I delved into any sort of book or article I could find to figure out what he was doing at the time of this album, clarinet equipment-wise. I read that Benny Goodman had studied with Reginald Kell in the late 1940s into the 1950s. By the time this album was recorded he had switched to double lip embouchure. My reaction? Ha – I switched to double-lip too! Well, for a year or two. I used it also to teach myself not to use too much jaw pressure and also not to bite when articulating. It sure helped but I eventually went back to single-lip because I felt it was hindering my saxophone playing (of all things!). But I think there are some very fine saxophonists that use a double lip embouchure.

BC: When did you first encounter Previn in the Boston Symphony?

TM: I remember first playing under André Previn with the BSO at Tanglewood in 1985. Elgar’s first symphony was scheduled to be rehearsed. When he walked on stage for the first rehearsal I was totally frozen seeing him. Like seeing a movie star – that reaction. I already had such tremendous respect for him. He came to conduct and perform with the BSO many times since and I came to respect him even more as a musician’s conductor. He was happy to just hang out with musicians and talk music or most anything. The first time André and I ever had any interaction off the stage happened to be on the back deck of the music shed at Tanglewood. I happened to be at one end of the deck and from far off at the other end of the deck I heard a voice from behind say, “Oh look – it’s one of the finest clarinetists in the world.” I turned around with a surprised face and saw André sitting with his assistant both looking at me. I quickly responded, “Where???”

BC: What brought you to consider asking Previn for a piece?

TM: In the 2002 symphony season André conducted his violin concerto with Anne-Sophie Mutter as soloist. As I was learning the clarinet part to the violin concerto I was struck by how well he wrote for the clarinet. By the end of the last concert I had decided to get the courage to ask him if he would write something specifically for the clarinet. I thought not to ask for a concerto but rather a sonata – something that would be performed more often. It was my small way of trying to add to the clarinet repertoire a piece that we all might have the opportunity to play and enjoy. To my surprise and delight, André agreed to write a clarinet sonata. He then asked if there was anything special I would prefer in the sonata, such as any sort of technical things I like. I told him I had no special requests or technical limitations other than I always love a simple, beautiful melody.

After agreeing to the commission, the only piece of the puzzle left was when it would be written and where would it first be performed. A few years passed and then at Tanglewood, something wonderful happened. BSO violist Mark Ludwig approached me about the sonata. There was an opportunity for Mark and his Hawthorne String Quartet to have a chamber concert during the 2010 Prague Spring International Music Festival and he thought it would be great opportunity to premiere the sonata as part of the program. After a BSO rehearsal, Mark and I saw André having lunch in the Tanglewood cafeteria. We approached him and asked if he thought perhaps the sonata could be written in time to be performed at the 2010 Prague festival. Not only did he say yes but said he would be delighted if he could perform it there with me. Mark and I were over the moon that he would agree to do this.

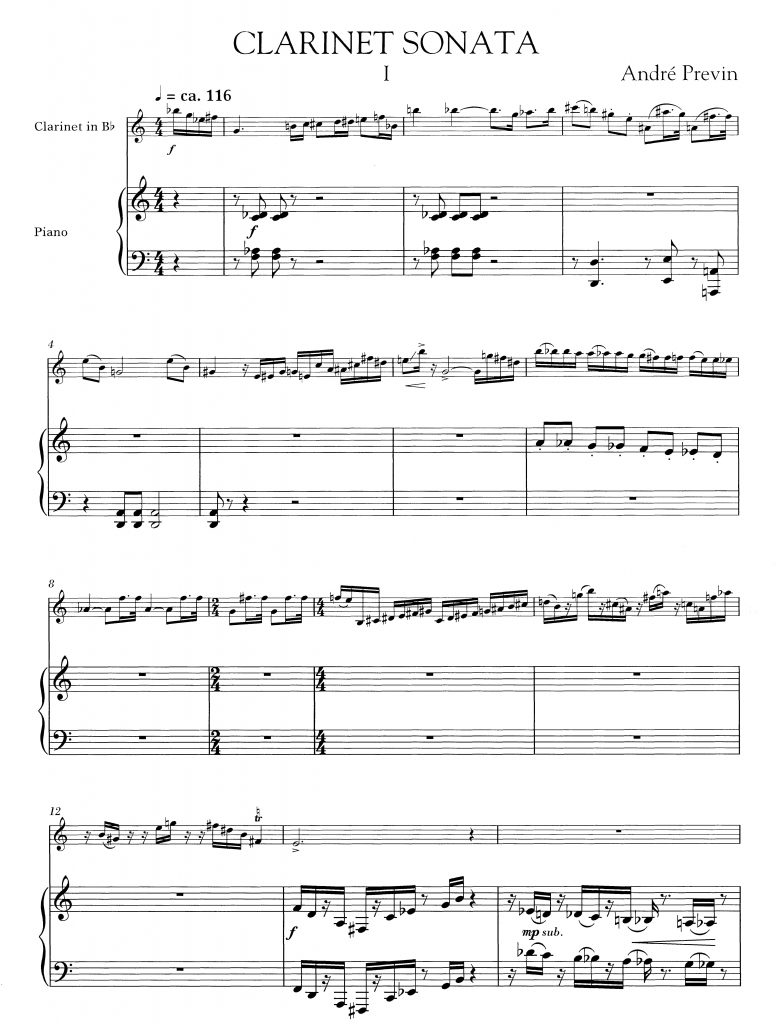

Sonata for Clarinet and Piano by André Previn, mm 1-14 ©2010 by G. Schirmer, Inc. All Rights Reserved. International Copyright Secured. Used by Permission.

BC: Previn had said, “I prefer to compose for artists I know. I knew Tom’s playing and admired it. And I was really looking forward to it.” So it seems like a mutual admiration society!

TM: I first received the sonata as a photocopy of the manuscript score – in C. Shortly after, I received an engraved B-flat clarinet and piano part. André and I didn’t have any communication until we met in Prague at the festival. We rehearsed almost every day for a week in preparation for the sonata’s premiere. I remember at one point asking him about articulations in some passages and he told me he wanted to leave that to me – to do whatever sounded best. In one passage in the first movement (starting at bar 27) André had indicated in the score “a little slower.” At the first reading, he burned through that passage and left me in the clarinet dust of the key of B. After we finished the movement I said: “I know you are the composer but you wrote ‘a little slower’ at bar 27 …” André responded, “Yes, I know. I wrote that because I wasn’t sure if I could play that passage in time, but it turns out I can.” I laughed and then spent most of the night in my hotel room quietly working on that passage so I could try to keep up with him!

A bonus in the sonata, if I may call it that, is the “Interlude” between the second and third (final) movement. The solo clarinet presents a simple, beautiful melody – reminiscent of a blues melody one might hear from the early jazz age in New Orleans. The piano quietly enters after a solo chorus by the clarinet. As the clarinet repeats the same melody, the piano harmonies become more and more complex and then slowly return to the simple harmony that the piano entered with.

It was an incredible experience to spend all those days with André rehearsing, having lunch or dinner together, and talking about music. He had worked with so many great musicians in his career – Billie Holiday and Charlie Parker among them! André himself was, of course, an incredible musician, pianist, conductor and composer. What a sound and technique at the piano he possessed! He was fearless, ferocious and also the most sensitive pianist I have ever played with. And André had such an incredible intellect and wit … and he was a sweet, sweet person.

As it happened, the Prague Spring International Music Festival of 2010 featured André Previn as composer, performer and conductor. We performed his newly written sonata on a chamber concert, along with Mozart’s Piano Quartet in E-flat with André and members of the Hawthorne Quartet, Mozart’s Quintet for Clarinet and Strings and Elliott Carter’s Gra for solo clarinet. A week later André conducted the Czech Philharmonic in a concert of his own Diversions for orchestra, Dvořák’s 7th Symphony and Copland’s Clarinet Concerto with yours truly as soloist.

It was during dinner after the chamber music performance that Mark Ludwig offhandedly remarked to André, “Now that you have written a clarinet sonata for Tom, why don’t you write a clarinet quintet for Tom and the Hawthorne Quartet?” André thought for a split second and then said “Sure, I’ll do that.” Once again, Mark Ludwig and I were over the moon.

BC: How is this quintet related musically to the Sonata?

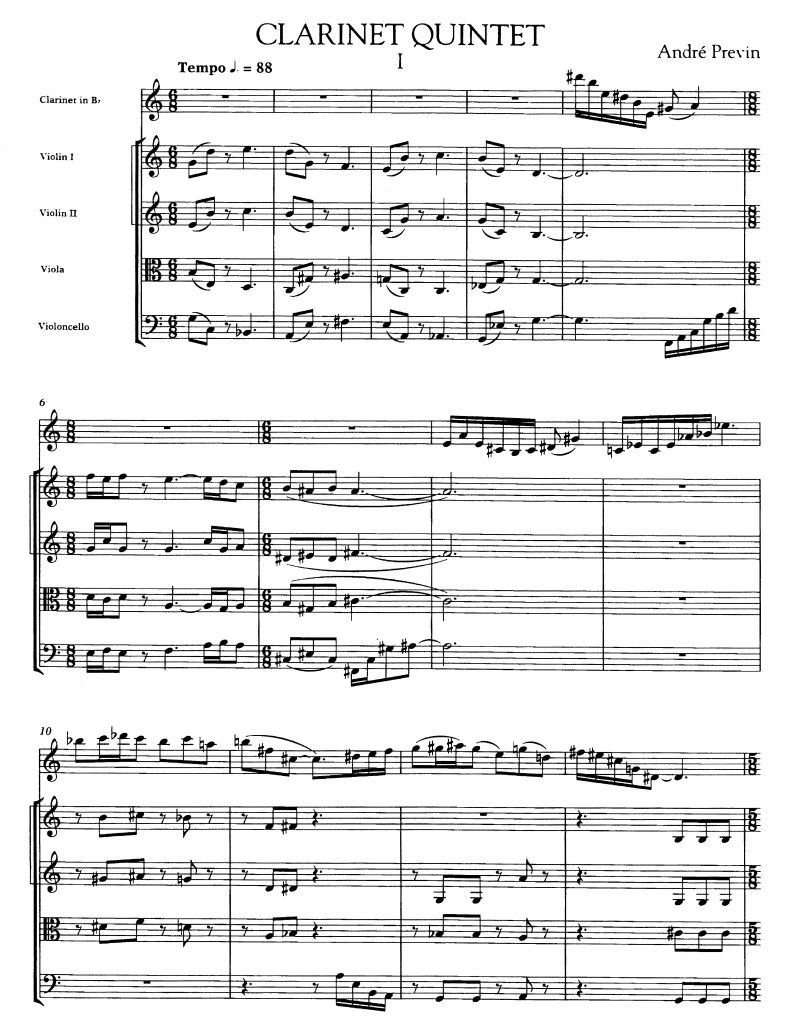

TM: The Quintet was commissioned by the Terezin Music Foundation as a living memorial to the composers and musicians of the Terezin concentration camp who perished during the Holocaust. It was given its premiere on Nov. 14, 2011, in Symphony Hall, Boston, at a Terezin Music Foundation gala. It is particularly appropriate that Previn write a such a work, with his Jewish family escaping in 1938 from Germany to Paris and then to Los Angeles in 1940.

Like the Sonata, the clarinet writing is “athletic” from a technical standpoint, and melodically satisfying. Both the sonata and the quintet have moments of humor, dry wit, sadness and nostalgia. The second movement of the quintet sets a very touching, melancholy tone and requires complete control of legato, particularly in the upper registers of the clarinet. The string quartet must manage some difficult harmonies and rhythmic twists and turns throughout the piece. The outer movements are full of fun for all players. I find that the last movement of the quintet in particular reveals André Previn’s delightful wit.

My purpose in commissioning André Previn was so that all of us in the clarinet world could have a piece by him to play. I am so thankful to André for writing a sonata for us. A special debt of gratitude goes to Mark Ludwig for having the chutzpah to then ask

for a quintet, to Carol and Joseph Reich for their support and generosity in the commissioning of the quintet, and to the Terezín Music Foundation for its role in bringing these two pieces to light.

Clarinet Quintet by André Previn, mm 1-13 ©2011 by G. Schirmer, Inc. All Rights Reserved. International Copyright Secured. Used by Permission.

BC: Changing to a subject often asked: Do you have any advice regarding mouthpiece and reed setup?

TM: Someone once asked me what setup I use when I perform the Artie Shaw Clarinet Concerto. I had never thought about using any different setup from what I use in the Boston Symphony or Pops when I play that concerto, other than a slightly shorter barrel to compensate for the vibrato and sheer volume you have to attain to be heard over a brass section. The rest of my clarinet, my mouthpiece, ligature and reed all remain the same, be it jazz or symphonic or chamber music. I make my reeds mostly or, when I’m in a “reed funk,” will sometimes play commercial reeds that I’ve adjusted. As far as reed making goes, I’ve tried several different reed making machines over the years with limited success but in the end I always feel the reeds I’ve made just using a reed knife and sandpaper always feel best to me. I can’t say they are any better than a good commercial reed. They simply feel more familiar to play and usually last a bit longer. The downside to making one’s own reeds is when they aren’t working properly you have only yourself to blame!

* * * * *

Reviews of the Sonata and Clarinet Quintet appeared in previous issues of The Clarinet: the printed music in Volume 42/3 (June 2015) and the CD in Volume 44/4 (September 2017). The CD is available from www.terezinmusic.org (TMF-161031).

The CD says “Previn plays Previn.” Perhaps “Martin plays Previn” is more true!

Bravo!

About the Writer

Bruce Creditor has enjoyed a diverse career in music including performance (the Naumburg Award-winning Emmanuel Wind Quintet, etc.), music publishing, record producer, music librarian and orchestra management as assistant personnel manager of the Boston Symphony and Boston Pops Orchestras.

Comments are closed.