Originally published in The Clarinet 49/3 (June 2022).

Printed copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

2021 ICA Research Competition Winner

Accommodating Learning Differences in the Clarinet Studio:

Private Teacher Experiences and Pedagogical Guide

by Shannon McDonald

Private clarinet lesson teachers have a higher likelihood of encountering students with special needs now more than ever before but may find that their lack of training in special education puts them at a disadvantage in terms of how best to serve these students. They may not have training in teaching special learners and may be unaware of pedagogical strategies that would benefit these students.

Extensive research has been conducted regarding the attitudes and perceptions of classroom music teachers on the inclusion of students with special needs in K-12 music classrooms, but very little study has been dedicated to the attitudes and perceptions of private music lesson teachers regarding inclusion of students with special needs in their studios. There has also been extensive research into the best pedagogical strategies for teaching music to students with special needs in the classroom setting, but little has been written to address strategies specific to the private studio. The one-on-one model used in lessons can benefit special learners because it allows the private teacher to individualize the curriculum, pacing and pedagogical strategies to fit each student’s needs; however, without proper training on pedagogical strategies for students with special needs, private teachers may find it difficult to set their students up for success.

The purpose of this study was to explore the attitudes and experiences of clarinet lesson teachers towards their private students with special needs, and to outline pedagogical strategies that clarinet teachers use with special learners. Using the data gathered in the study, a pedagogical guide outlines strategies that clarinet teachers can use with their students with special needs.

Participants in this study were given a survey addressing their attitudes and experiences with special learners in their studios. Eighty clarinet lesson teachers throughout the United States completed the survey. The participants showed a range of educational backgrounds and professional experiences. Three main research questions guided this study.

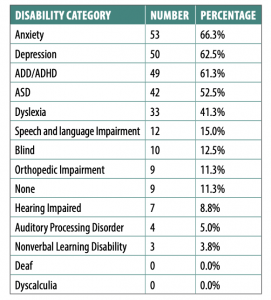

Table 1: Number and Percentage of Students Encountered by Participants by Disability Category

Research Question 1: What experience do clarinet lesson teachers have with students with special needs in their studios?

According to participants, the most common disabilities and learning differences that private clarinet teachers reported encountered in their students were anxiety, depression, attention-deficit disorder (ADD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and dyslexia (Table 1). Only 11.3% reported that they had never had a student who disclosed a diagnosed special need.

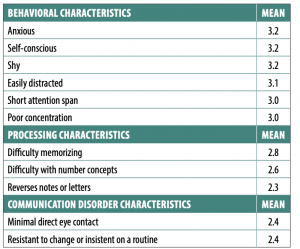

Since clarinet lesson teachers do not always have access to a student’s diagnosis, participants were asked if they had students that displayed characteristics associated with common disabilities or disorders. Participants ranked a series of questions about behavioral, processing and communication disorder characteristics using a Likert-scale with the following coding: 1-never, 2-rarely, 3-sometimes, 4-often (see Table 2).

Table 2: Characteristics Encountered by Private Clarinet Teachers in Their Studios

(1-never, 2-rarely, 3-sometimes, 4-often)

Research Question 2: What attitudes do clarinet teachers have concerning inclusion of students with special needs in their studios?

Over 57% of participants reported that they agreed with the statement, “I believe students with special needs can be successful playing the clarinet.” However, only 33% of participants reported feeling comfortable teaching students with special needs.

A Pearson Correlation Coefficient was conducted, which suggested a moderate correlation between teachers who felt comfortable with inclusion and those that had previous training or had taken classes pertaining to teaching special learners. With this in mind, it is important that teachers and pedagogues receive training in special education for them to feel effective and confident including special learners in their lessons and classrooms.

The Pearson Correlation Coefficient also indicated a moderate correlation between a teacher’s comfort level with inclusion and whether they had previous experiences with individuals with special needs – in and out of the studio. Unfortunately, teachers who do not feel comfortable teaching special learners may not be likely to include them in their studios. However, this correlation shows that if teachers include students with special needs in their studios, their overall comfort level teaching these students may rise.

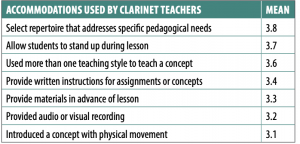

Table 3: Accommodations Used by Clarinet Teachers

(1-never, 2-rarely, 3-sometimes, 4-often)

Research Question 3: What pedagogical strategies do clarinet teachers use with students with special needs in their studios?

Participants were asked whether they use specific accommodations with their students with special needs (see Table 3).

Based on the results of the study, private clarinet teachers encounter students with learning differences and special needs in their studios. Though many teachers are already using strategies and accommodations that benefit special learners, many are not aware which accommodations are appropriate for which characteristics/disabilities.

With the information gathered in the study and from other resources listed at the end of this article, the author created a pedagogical guide for clarinet teachers to use with their students with disabilities. The guide lists examples of common behaviors, characteristics and disabilities exhibited by students and provides strategies and accommodations to use specifically for those students. Further information about this study and the accompanying pedagogical guide can be found at www.shannonmcdonaldclarinet.com/accommodating-learning-differences.

Excerpts from the Pedagogical Guide

Pedagogical Strategies for Accommodating Behavioral and Emotional Characteristics

Behavior: A student who is easily distracted.

Strategies:

1 Clear the teaching area of anything distracting. Look around your studio or teaching area. Something that you may not notice such as a ticking clock or a piece of paper fluttering from a fan can be extremely distracting for a student who struggles with attention. Try the following activities to find potential distractions in your studio.

- Sit alone in silence in your studio for a few minutes. Close your eyes and listen. Make note of any extraneous sounds that you hear. If possible, remove the object eliciting the sound.

- When a student is distracted, follow their gaze to see what has caught their attention. A brightly colored poster or a shelf full of knick-knacks can be removed or placed out of the student’s line of vision.

2 Create and use a lesson notebook. Distracted students may have trouble remembering directions and instructions once the lesson is over.

Behavior: A student who has a short attention span or poor concentration.

Strategies: When a student has difficulty keeping their attention on any one task, pacing of the lesson can be essential for success. It is important for a teacher to be flexible with their lesson plans and be willing to adapt when necessary.

1 Plan activities that last only short increments of time, such as 5 or 10 minutes. Be flexible with this, and be open to bouncing back and forth between activities if that is what the student needs to remain engaged.

2 Change the modality.

Example: The student is working on a technical piece but is losing focus. Ask the student to clap the rhythm or sing/finger the piece. Changing the modality can help the student refocus on the same activity.

3 Provide a written schedule for the lesson. This can help the student focus when they know there is a concrete beginning and end to an activity. Be as detailed as necessary.

4 Limit the amount of time that you talk. This is especially important for private teachers with little experience. Often teachers don’t realize how much time they spend talking at

a student.

5 Incorporate music styles that interest the student.

Example: The student enjoys video game music. Add these kinds of pieces to their repertoire in ways that will benefit the student. If they are working on technique, find a piece that allows them to work that aspect. Use music that interests them as their “etude” pieces. Duets of music that the student enjoys can also be used for sight-reading practice.

Behavior: A student that is restless, overly active, or unable to

sit still.

Strategies: Students who learn best kinesthetically may need to move around during a lesson. This is also true for students who have behavior disorders that make sitting still difficult. There is no rule that says a student must sit for an entire lesson. The following strategies can be used for fidgety students.

1 Encourage the student to stand while playing the clarinet.

2 Work in break time where the student can stand and stretch or move around the studio. Do this consistently and in every lesson. Include this break time on the lesson schedule.

3 Practice rhythms by clapping, tapping, marching, or by using non-pitched percussion instruments such as bells, sand blocks, or rhythm sticks.

4 Allow students to respond to questions with a dry erase board.

5 A student that is verbally overactive can benefit from a lesson schedule where you work in “playing time” and “talking time.” Redirect them gently when they talk during playing time.

Pedagogical Strategies for Students with Learning Disabilities and Processing Disorders

Processing disorder characteristic: Student has difficulty reading and processing written instructions/assignments.

Strategies:

1 Audio record lessons assignments and instructions for the student.

Example: Use a voice recorder app on their smartphone. If they do not have a smartphone, you can record on your own device and send the file to their email.

2 Type assignments and instructions in a document, and encourage the student to use a text to speech program to read it out loud to them.

3 Enlarge print on any text instructions and assignments.

Processing disorder characteristic: Student has difficulty reading music.

Strategies: Students with various learning disabilities can struggle to read music for many different reasons. It is important to try many strategies to see what works best for the individual.

1 Use of color can be very helpful to students who have difficulty reading music due to visual stress or a specific learning disability.

Example: Use color overlays over sheet music.

Example: Print sheet music on colored paper (I’ve had particularly good success with lavender paper).

Example: Color code fingerings and have scale/arpeggio exercises printed in color, with each note the same color of the fingering.

2 Enlarge sheet music.

3 Isolate sections of the sheet music by cutting and pasting.

Example: If a student is working on a difficult or visually busy section of music, make a photocopy, then cut out the section. Paste it onto blank paper.

4 Use a highlighter to mark certain information, such as key changes or accidentals.

5 Teach music using different modalities.

Example: Allow the student to learn by watching your fingers or by listening to either a recording or to you playing the music.

Processing disorder characteristic: Student has difficulty with working memory.

Strategies: Working memory is the process of taking stored information and using it to achieve a task. Students with learning disabilities that affect working memory can find it difficult to listen to, remember or follow directions.

1 When giving directions, reduce the number of steps in the direction list.

2 Reduce the amount of information that the student must recall from memory.

Example: Provide a sheet with fingerings, definitions, scales or directions. Keep it displayed on the music stand at all times.

3 Choose repertoire that is appropriate for the student. If they struggle with working memory, complex music may be very difficult.

Example: Provide music with familiar tunes or repetitive music.

4 Provide a simplified version of new music, then gradually add elements back to the music over time.

Processing disorder characteristic: The student struggles with number concepts (including counting and rhythms).

Strategies:

1 Teach rhythms without the clarinet or the melodic notes.

2 Teach rhythms with manipulatives.

Example: Seeing rhythms represented visually by length of the manipulative can help students understand abstract rhythm concepts. Paper cut to different lengths and laminated can be used to build rhythms. Draw the note onto the paper so that they can see both the note and the visual representation of the value. Another fun idea is to use Lego blocks. The different size Legos can represent different rhythmic values, and the student can snap them onto a Lego board as they build rhythms. Draw the notes onto the Legos with a sharpie. Students can then see a concrete representation of the rhythms in their music. This is also a great strategy for kinesthetic and visual learners.

3 Teach rhythms by ear.

Pedagogical Strategies for Students with Sensory Impairment and Sensory Sensitivity

Visual Impairment

Visual impairment and blindness can affect a student’s language development, intellectual development, social development, and academic development, depending on the severity and onset of the vision loss. Children often learn through imitation; however, children with early onset vision impairment lose this opportunity. In general, students with vision loss may learn best through kinesthetic and aural modalities.

Below are strategies and suggestions for assistive technologies that may aid students with vision loss or blindness find success in the clarinet studio.

Impairment: Visual Impairment/Blindness

Strategies:

1 Enlarge sheet music and text.

2 Use Braille music.

Example: Not every musician with visual impairment/blindness will read Braille. If a student intends to pursue music as a career, Adamek and Darrow advise that the student learns Braille music. There are websites that provide Braille sheet music, as well as software that will translate music into Braille.

3 Provide recordings before a lesson of any new music so that the student can be aurally familiar with it.

4 Teach music by rote instead of by reading music.

5 Choose repertoire from music that is already familiar to

the student.

6 Choose repertoire that is simple and easy to memorize (repetitive).

Example: Solo pieces in ABA form, rondo, and short sonata-allegro form could be easier for a student to memorize.

7 Audio record lesson assignments and instructions. Use a voice recorder app on their smartphone. If they do not have a smartphone, you can record on your own device and send the file to their email.

8 Type assignments and instructions in a document and encourage the student to use a text to speech program to read it out loud to them. There are many programs and apps that are free to use. Ask the student if they are already using a similar program or app.

Hearing Impairment

Hearing loss can be mild to severe and can affect a student’s language development, social development, and academic achievement. There are many assistive devices that a student may already possess to aid in their hearing, such as hearing aids or cochlear implants. It is important to note that, though these devices can dramatically impact the student’s overall hearing, they can change the way that music sounds to the student. Hearing aids increase the volume, but do not make sounds clear. Some cochlear implant users report that there are changes in pitch and timbre from before they had the implant.

Impairment: Hearing Loss, Hard-of-hearing

Strategies:

1 Remove items that produce extraneous noise.

2 Face the student. Many individuals with hearing loss may rely on lip-reading as well as their hearing to understand.

3 When giving directions or assignments to a student, write them down as you speak so that the student can hear and see what you are saying.

4 Tapping the beat with your hand or conducting can help the student by giving them a visual cue of the beat while they play.

5 If the student uses American Sign Language (ASL), ask them to teach you signs that may be helpful during lessons.

6 Use an app for tuning that displays a visual representation of the intonation.

7 Use a metronome app that vibrates and place the phone on the student’s leg while they play.

8 Use a metronome app that shows a visual representation of the beat, such as flashing or color changes.

Sensory Sensitivity

Some students may be sensitive to sensory stimuli such as bright lights or loud/high pitch sounds. If a student often covers their ears when they hear loud sounds or complains about the brightness of the lights, you can make modifications to the environment and use assistive devices to better serve the student.

Sensitivity: Lights

Strategies:

1 Dim the lights before the student arrives for a lesson and keep them dimmed. If you are in a room that has only an overhead light source (such as a practice room at a school), bring a lamp or stand light to use instead of the overhead lighting.

2 Use natural lighting or incandescent lighting when possible. Individuals with light sensitivity seem to be more sensitive to fluorescent lighting.

3 Suggest that the student wear sunglasses or a visor to block overhead lights during the lesson.

Sensitivity: Loud or high-pitched sounds

Strategies:

1 Allow the student to wear musician ear plugs while playing or listening to music.

2 Choose music that will not upset the student’s sensitivity.

Example: Music that stays in the altissimo range for long periods of time may be bothersome to a student with sound sensitivity. Limit the amount of time spent on altissimo study.

3 Prepare the student for loud or high noises.

Example: Remind the student to put in their ear plugs or cover their ears when you are about to demonstrate playing something loud.

4 When listening to recordings, ask the student beforehand if they prefer using earbuds.

Strategies for Students with Physical and Orthopedic Impairments

Physical and orthopedic impairments can affect students in many ways; however, the most impactful impairments will be ones that interfere with the student holding the clarinet or covering the holes. It would be simple to dismiss a student with a physical disability that affects their hands, arms or fingers, but technology exists to accommodate those students. Below is a list of physical impairments that could affect the way a student holds or plays the clarinet, and possible modifications to aid the impairment. Many instrument makers, repair persons and artisans might be able to make modifications that suit the specific needs of a student. If none of the modifications below will work

for the student’s unique needs, contact an instrument repair person and see what is possible.

Impairment: Student cannot cover the holes fully.

Clarinet modified with plateau keys.

Photo by Wolfgang Lohff

Modification: Plateau key clarinets

- Plateau key clarinets are modified to have the tone holes covered, similar in style to a bass clarinet or saxophone. Students with extremely small hands or narrow fingers may find it difficult to fully cover the tone holes of a clarinet. This is especially true for the tone holes on the bottom joint. Students with reduced movement in their hands (such as with arthritis, cerebral palsy, or other motor skill impairments) may also find plateau key clarinets helpful. Clarinets made with plateau keys can be difficult to find, but there are some manufacturers. I would recommend that the teacher play-test any unknown instrument brands before recommending them to your student.

- Standard tone hole clarinets can also be modified to have plateau keys. Many reputable instrument makers offer this service. This can be a good way to provide a student with a physical impairment an opportunity to play on a professional quality instrument and allow for the modification.

Impairment: Student has difficulty holding or balancing the clarinet.

Modification: Neck strap

- Clarinet neck straps are very popular among clarinetists with or without disabilities. They can help balance the clarinet for students with weak hands and can take some of the weight off the right thumb. It is important that the neck strap is made for the clarinet (not a saxophone strap) and is elastic.

Modification: Kickstand

- A clarinet kickstand is a thin rod that attaches to the thumb rest of the clarinet and rests on the chair between the clarinetist’s legs. This can be a good option for students who need more weight bearing or balance assistance than a neck strap can provide.

Modification: Ergonomic thumb rest

- Ton Kooiman manufactures different styles of thumb rests that shift the support of the clarinet from the first knuckle of the thumb to the space between the first and second joint. An ergonomic thumb rest could be a good solution for students with arthritis, tendonitis or carpal tunnel syndrome.

Impairment: Student cannot hold the clarinet.

Modification: Stands designed to hold musical instruments at the height of the performer exist. MERU, a charity that provides assistive products to children with disabilities, along with the OHMI Trust, which makes musical instruments for people with disabilities, has produced a trumpet and trombone mount that connects to a cymbal stand. They have not produced a clarinet mount as of the publication of this guide, but it is possible that such a product will be developed in the future.

Impairment: Student has the use of only one hand.

Modification: One-handed clarinet

- Peter Worrell manufactures a fully chromatic one-handed clarinet that can be used by either the left or right hand. It comes with a unique support system so that the clarinetist does not need to support the clarinet with their thumb. It also comes with a piece that can attach the clarinet to a microphone stand, which will fully support the clarinet while the clarinetist plays with one hand.

References

Accommodations for students with dyslexia. (2020). International Dyslexia Association. Retrieved from https://dyslexiaida.org/accommodations-for-students-with-dyslexia/

Adamek, M. S., & Darrow, A. A. (2010). Music in special education. American Music Therapy Association, Inc.

Children and youth with disabilities. (2019). National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cgg.asp

Darrow, A. A. (1999). Music educators’ perceptions regarding the inclusion of students with severe disabilities in music classrooms. Journal of Music Therapy, 36, 254-273.

Exceptional students and disability information. (2020). National Association of Special Education Teachers. Retrieved from www.naset.org/index.php?id=exceptionalstudents2.

Green, S., & Reid, G. (2016). Dyslexia: 100 ideas for secondary teachers. Bloomsbury Education.

Hammel, A. M. (2017). Teaching music to students with special needs: A practical resource. Oxford University Press.

Hammel, A. M. & Hourigan, R. M. (2017). Teaching music to students with special needs: A label-free approach. Oxford University Press.

Learning disorders in children. (2021). Centers for Disease control and Prevention. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/childdevelopment/learningdisorder.html

McCord, K. (2016). Specified learning disabilities and music education. In D. Blair & K.

McCord (Eds.), Exceptional Music Pedagogy for Children with Exceptionalities: International Perspectives (pp. 176-196). Oxford University Press.

McCord, K. (2017). Strategies for Creating Inclusive Music Classes, Ensembles, and Lessons. In Teaching the Postsecondary Music Student with Disabilities (pp. 39-62). Oxford University Press.

Sec. 300.8 Child with a disability. (2018). Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Retrieved from https://sites.ed.gov/idea/regs/b/a/300.8

Sensory issues. (2021). Autism Speaks. Retrieved from www.autismspeaks.org/sensory-issues.

Symptoms and diagnosis of ADHD. (2020). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/diagnosis.html

Working memory: The engine for learning. (2020). International Dyslexia Association. Retrieved from https://dyslexiaida.org/working-memory-the-engine-for-learning/

Worrell, P. (2020). Peter Worrell Instruments. Retrieved from www.peterworrell.co.uk/index.htm.

About the Writer

Shannon McDonald serves as Adjunct Instructor of Music at Texas Woman’s University where she teaches music history, music theory and clarinet lessons. She holds a D.M.A. in clarinet performance from the Frost School of Music at the University of Miami and a master’s degree in instrumental pedagogy from Texas Woman’s University. In addition to teaching, Shannon is an avid chamber musician, and has performed at many national and international music conferences.

Comments are closed.