Originally published in The Clarinet 50/3 (June 2023).

Printed copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

International Spotlight

How to Play “Pitch Bending Tones” on the Clarinet

by Di Xiaoyan and Zhai Xingxing

Please click here for the Chinese version

In European classical music, the frequency of a given note is fixed, while in Chinese traditional music, it can be fixed or unfixed, and with pitch variations, dynamics and timbre may also be changed.

The Chinese call a tone with varying frequencies the qiang yin,1 which varies according to the shape of a gradually changing pitch, the magnitude of the change in pitch, the length and frequency of the change process, and other factors.2 Qiang yin can be divided into four forms: chuo, zhu, yin, and nao. Chuo (╯) is a glide upward, and zhu (╮) is downward. Yin (~) combines rapid downward and upward, like vibrato in European classical music, but with a larger interval. Nao’s (~or ∽) change range is of a much larger frequency than yin, and according to the direction of the sound change, it can be divided into chuonao and zhunao.

The extensive use of qiang yin is the most important feature of pitch in Chinese traditional music, which is related to the intonation in Sino-Tibetan languages.3 In addition to Chinese traditional music, qiang yin is also used in Indian and Arab classical music, American blues, and Jewish music, as well as in some orchestral works of special ethnic styles; it can even be found in the assigned works of international clarinet competitions.

Qiang yin is one of the main factors in unique style of Chinese traditional music, widely used in folk songs, instrumental music, opera, ballad singing, and other art forms. The four forms chuo, zhu, yin, and nao are commonly used performance techniques in Chinese instrumental music, on instruments including the qin, zheng, erhu, pipa, and bamboo flute. There is not a corresponding vocabulary for qiang yin in European musical terms, so Western musicians call it “unfixed tone,” “tone with intonation,” “moving tone,” “glissando,” “bending tone,” and so on. The authors believe that the theory and performance experience of Chinese music qiang yin are relevant to clarinet performance; as the techniques of tongue, mouth, breath, and fingers are connected and precisely controlled, qiang yin can greatly broaden playing skills, and interpretation of different regional styles of music, thus enhancing musical expressiveness.

The concept and method of performing qiang yin are described as follows:

1 Chuo (╯) is a glide upward, and is commonly used in blues, klezmer, and Chinese music. Playing the chuo on the clarinet, we should completely control the air, embouchure, and fingers, and they must work together so we can gradually change the pitch upward. With constant air, the fingers lead the pitch movement like a forerunner, while the air and mouth are moving as well.

As an exercise, start playing from clarion A to high C. The embouchure moves from a relaxed position to a tighter one, and the air changes from a slow to a fast speed. This way, the music can easily get up to the minor third above. The embouchure should not be too relaxed at the beginning and the air should not be too slow, otherwise the intonation of the starting note will be affected, becoming too low. The key to playing chuo is a soft and consistent movement of the fingers; embouchure and air are only fine-tuning. The chuo could reach a frequency change of an octave above. But no matter the frequency change, the main difficulty is consistency. When practicing, it is our advice to play the high register first. Then continue with the top register, and finally the middle register. Since it is difficult to play chuo in the lowest register on the clarinet, players should replace chuo by playing scales instead.

Béla Kovács’s Sholem Alekhem, rov Feidman (Example 1) uses the chuo in the top register. In this excerpt at the end of the third measure, we should move our finger from high C to D by tightening the embouchure gradually. In the meantime, while moving the tongue position upward and accelerating the air speed, an agile articulation must be ensured. In this way, we can produce the effect of gliding up and express the feelings required for this piece.

Example 1: Sholem Alekhem, rov Feidman by Béla Kovács

The glissando from Wen Ziyang’s Autumn Sun reflects Chengdu City (Example 2) should be divided two sections in order to be performed with better results. First, from the starting note F to C, then from D to high B. Once achieved properly, the separated parts should be linked up. When playing the first section F to C, chuo can be replaced by playing a scale. But in the second section from D to high B, chuo should be used. It should be performed as in the Gershwin Rhapsody in Blue clarinet solo.

Example 2: Autumn Sun reflects Chengdu City by Wen Ziyang

2 Zhu (╮)is a glide downward. At first, we should practice zhu with descending major second intervals and then expand to bigger intervals. Zhu is linked with many different techniques, including tongue, embouchure, air, fingers, and other aspects. Among the different qiang yin, zhu is the most difficult technique to play on the clarinet. We must be patient when practicing it. This technique is widely used in klezmer music and Chinese traditional music.

When playing, first lower the tongue position, relax the chin slightly, slow down the air speed, and adjust the direction of exhalation downward, so the process of change is gradual, slow, and full. Like the chuo, zhu is easier to practice when starting from the high register. When falling a large interval, it can be assisted by the fingers. When the fingers are ready, pull down the chin and slow down the exhalation to make zhu and to reach the maximum interval downward.

A Hebei Opera Tune was arranged by Yan Shaoyi and adapted by Ni Yaochi. In Example 3, zhu is used to simulate the timbre of banhu (a Chinese fiddle). This skill is a challenge for clarinetists. Playing zhu on altissimo E, first lower the tongue position, then slightly relax the embouchure along with soft finger movement to make the special effect. To play zhu from high D down to B, it is necessary to adjust the pitch with the embouchure, tongue, and air, all while not pressing any key of the clarinet. Zhu is a very difficult technique, but when playing, it is preferable not to relax the embouchure before your tongue and air are ready.

Example 3: A Hebei Opera Tune arranged by Yan Shaoyi and transplanted by Ni Yaochi

3 Yin (~) is commonly used in folk music from all over the world. It is a kind of qiang yin in which the sound changes regularly around the given note. It could be mistaken as the vibrato of Western classical music. But it differs because its frequency is faster, its amplitude is greater, and the skill to perform it on the clarinet is also different. Vibrato can be played with the breath, but yin must be done with the chin.

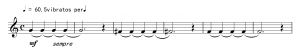

First, we can play a note with accents (>). A big amount of air should be prepared. Once the note comes out, a rapid decrescendo has to be done for the accent effect. Then, we can play a long note with many accents, making the sound vibrate continuously and evenly, as in vibrato in classical music. And in order to reach more dramatic results, the chin should start to move regularly. It is best to start playing yin in the middle register as shown in Example 4, moving the chin up and down five times per beat; on each movement cycle the pitch should come back to the given note. Next, increase the chin movement and increase the vibration frequency, with constant stability. After that, practice the higher and lower register.

Example 4: Practicing yin

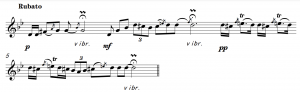

When playing Béla Kovács’s Sholem Alekhem, rov Feidman (Example 5), move the chin with the sound of “ya ya ya ya ya” when playing longer notes, which can show the characteristics of klezmer music. In Swan Goose (Example 6), adapted from a Chinese Mongolian folk song, the melody is long and slow, and its artistic concept is wide and far away. The use of yin is helpful to express delicate emotions and reflect the traditional Chinese music style.

Example 5: Sholem Alekhem, rov Feidman by Béla Kovács

Example 6: Swan Goose arranged by Michele Mangani

Jörg Widmann, a German clarinetist and composer, not only uses microtones and extreme dynamics in his work Three Shadow Dances, but also incorporates yin, chuo, and zhu (Example 7) to make the music unpredictable and have distinct modern characteristics. When playing altissimo F-sharp, it is advisable to use chin tremor to enhance the effect of yin. When playing altissimo D-flat in the sixth measure, it should be played softly first, but then gradually increase the volume, slightly releasing the chin, and at the same time slightly adjusting the direction of the exhalation downward, Finally, play with the yin technique when reaching the high C, to highlight the personality of the music.

Example 7: Three Shadow Dances by Jörg Widmann

4 Nao (~or ∽) is a technique characteristic of several folk musics around the world. It’s one of the types of qiang yin in which the sound starts from chuo to zhu (up, then down), or from zhu to chuo (down, then up), then finally returns to the given note. According to those two different directions of the glide, there are two names are given to nao: chuonao and zhunao.

To play chuonao on the clarinet, we should pay attention to finger movement at first. The fingers lead the pitch movement while the air and mouth are moving as well, and then play zhu, repeating several times. When playing zhunao, at first we should pay attention to the tongue, gradually moving down the tongue position, relaxing the embouchure, and slowing down the air speed. After that we can play chuo, and repeat several times.

When practicing chuonao, we should work on the left-hand part first. Start from the clarion G, then continue by working on the right hand from clarion D. Gradually slow down the process of chuo, increasing the pitch change, finally connecting the fingers of both hands. Then practice the high register and the middle register. Zhunao can be practiced from clarion high C or B. First, practice the left-hand part, using zhu to glide to clarion G, and then practice the right-hand part, making zhu reach the clarion D. Then connect the fingers of both hands, as if the tone is slowly drawn in a circle and gradually enlarged and rounded (the shape of ∞).

If nao and yin are linked, we call it yinnao. When playing yinnao, at first the nao should be done, and then play yin. To play yinnao the frequency should change regularly; if combined with the chin movement, the effect is more obvious. Huang Anlun composed Caprice for Clarinet and Piano (Example 8), re-arranged from the northern Shanxi folk song “The Drovers Spirit.” In the fourth bar (from F-sharp to B) and the seventh bar (around the F-sharp), we should play chuonao and zhunao respectively. It helps to make the music flow while conveying the uneasy mood of the girl, hoping for her lover to come back.

Example 8: Caprice for Clarinet and Piano by Huang Anlun

In the Ballad of Spinning Wheel, adapted from a Korean folk song (Example 9), we should adopt nao when playing clarion G, imitating the big vibrato “shaking note” in Korean music, to highlight that national style.

Example 9: Ballad of Spinning wheel, Korean folk song

It is worth mentioning that different brands of clarinets and reeds will produce different effects of chuo, zhu, yin, and nao. But the fundamental factor is the player, as their technique control and sensitivity plays a big role in achieving these effects. Therefore, the performers should make further adjustments in practice to achieve better artistic results.

With the rapid development of the world, its music has been widely spreading, reaching every corner. At the same time, Eastern and Western cultures have been deeply integrated. Musical instrument timbres have been further developed, and different types of performance techniques have been shared and learned from each other, effectively promoting the modernization of the musical art. Composers use different musical ideas for the clarinet in chamber music, and orchestral works that require a variety of techniques to perform. Mastering the qiang yin can help not only to interpret the modern works of European and American music, but also to understand the styles of various ethnic musics in the world, including Chinese traditional music—which in our opinion is a necessity for the enrichment of the clarinet. This will not only benefit the diversified development of clarinet performance, but also promote the modernization of the art of clarinet playing.

Endnotes

1 Du Yaxiong, Chinese Music Theory (Shanghai Conservatory of Music Press, January 2017) 1st edition, p. 100.

2 Mao Yurun, “Zhou Wenzhong’s treatise on single note,” Music Art no. 1 (1985), 86.

3 Du Yaxiong, “Fundamentals of Chinese Music Theory and Its Cultural Basis,” Eurasian Studies Yearbook 71 (1999), 34-80.

Comments are closed.