Originally published in The Clarinet 46/4 (September 2019). Printed copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

Caroline Schleicher-Krähmer: The First Female Clarinet Soloist

by Nicola Buckenmaier

“This artist delivered, supported by the Musikverein, a performance in which she fully demonstrated her abilities on the clarinet, the violin, and the piano and did leave no doubt that the first of these instruments is fully under her control, she masters great difficulties with even greater nonchalance, her sound is seldom outperformed; one believes to hear a harmonica of pure mood, and her level of piano will be rarely reached.”1

This is how a critic described the public concert of Caroline Schleicher on March 17, 1821, in Speyer, Germany. It was the prelude to a concert tour that would last several months and take her as far as Vienna and to the imperial court.

Nearly all of these aspects are exceptional: A woman that traveled all by herself around 200 years ago, performing publicly as an instrumentalist without being perceived as improper, mastering three instruments on a professional level of which two were considered completely inappropriate for women – the violin and the clarinet. The fact that Caroline Schleicher’s concert in Speyer and her multiple other concerts were discussed by the general public was rather unusual for this time.

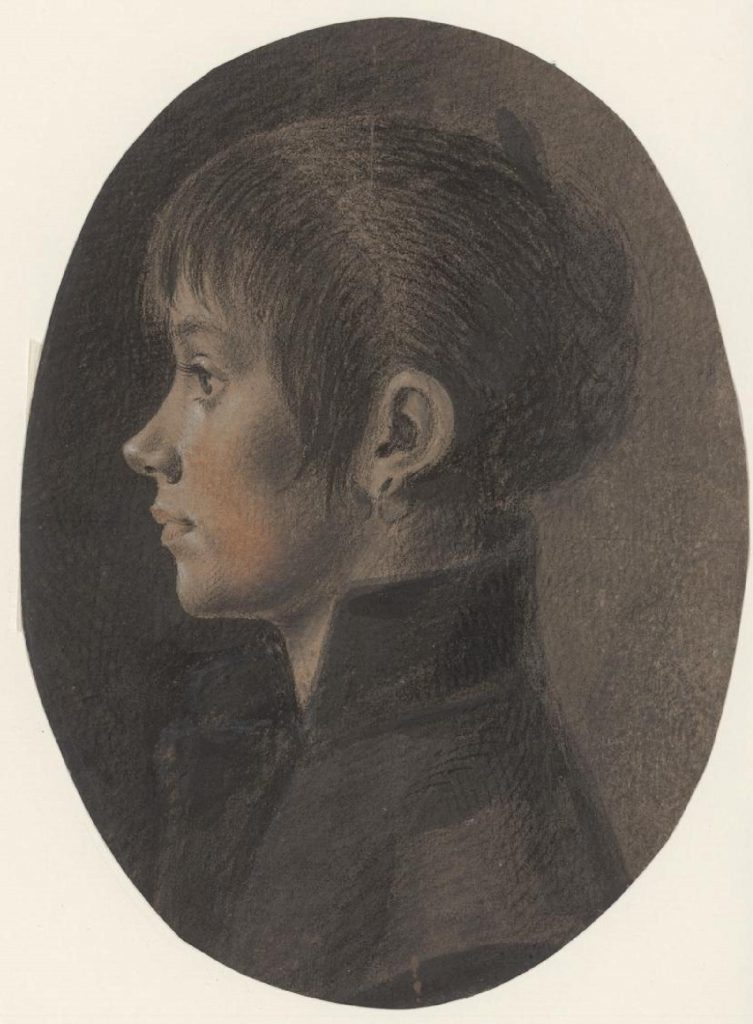

Caroline Schleicher-Krähmer, Zurich

Zentralbibliothek Zürich, Graphische Sammlung und Fotoarchiv

Caroline Schleicher was born on December 17, 1794, in a small town in southern Germany called Stockach. The daughter of the professional bassoonist Franz Joseph Schleicher (1767–1819) and the Swiss musician Josepha Strassburger (1767–1826), she was baptized on the same day with the name Maria Carolina. She was the sixth child of 13, seven girls and six boys. All children were given to a foster family once they were 3 months old. This enabled the Schleicher couple to go on concert tours together.

Only three of the children survived their infancy: Caroline’s older sister Cordula (1788–1820), Caroline herself, and a younger sister called Sophie (1796–1825). All three children received their first lessons in violin and singing from their mother when they were 5 years old. Josepha herself originated from a very musical family. Besides singing she also mastered the violin and the clarinet. Later, at the age of 7, all three daughters were taught the piano and at the age of 9, the clarinet.

While Napoleon covered all of Europe with wars, Franz Joseph Schleicher was employed as Regimentskapellmeister (regimental music director) in the garrison town of Ellwangen, Germany. Caroline received her first piano lessons at the age of 7 from the Chorregent (choirmaster) Melchior Dreyer (1747–1824)2 and about two years later began the long-desired clarinet classes with her father. It was certainly a fortunate coincidence that Caroline and her sisters had the privilege of being raised in such a music-oriented family as there was no formal education at that time – particularly not for female musicians. The numerous musicians in the professional and private environment of the family also had a great influence on all three girls. For example, when Franz Joseph accepted employment as a chamber musician of the king of Wuerttemberg, his daughters received lessons in violin from one of his orchestra colleagues.

A permanent appointment at court provided a certain regular income, but limited one’s personal freedom. To go on lucrative concert tours, the approval of a leave request was required. As those requests were frequently rejected, Franz Joseph Schleicher preferred shorter engagements at different courts and, similar to Leopold Mozart before him, diligently taught his children in music so they could go on concert tours all together. In 1804, Franz Joseph Schleicher finally sold his house in Stockach and traveled with his family to Tyrol in 1805. The family’s intention to continue their journey to Italy was thwarted by the Third Coalition War against Napoleon. The “Musikalische Kleeblatt” (“Musical Trefoil”), featuring Franz Joseph, Cordula and Caroline, traveled to Switzerland instead. There Franz Joseph and Cordula were employed in both musical societies in Zurich.

During this time the oldest daughter Cordula liberated herself both professionally and privately: In August 1808 Cordula placed an advertisement in the Zürcherische Wochenblatt (Zurich Weekly) offering lessons in clarinet, violin, piano and guitar as well as singing.3 December 1808 marked the beginning of a dispute between father and daughter: Franz Joseph Schleicher demanded from one of the Zurich musical societies that he, as the family head, should be paid the full remuneration, including his daughter’s share. She instead demanded to receive her compensation separately. The Musical Society decided to pay out Cordula’s share separately and to remain neutral in the family dispute.4 Shortly afterwards followed the private detachment of Cordula from her father. On April 11, 1809, she married, against her father’s will, Ernst Gottlieb Metzger, a goldsmith from Pforzheim, Germany.5 In the reformed City of Zurich the last Catholic Mass dated back to April 1525, exactly 284 years ago. Practicing the Catholic religion was only permitted again in 1807. Cordula’s marriage was the first Catholic wedding ceremony in Zurich in almost 300 years.

Cordula’s appointment as permanent musician at the Zurich Musical Society was renewed in the same year, 1809, while that of her father was terminated. In the following years, Cordula established herself as a professional clarinet player and performed multiple times as soloist, for example with the clarinet concertos of Crusell, Goepfer and Krommer.6 On November 16, 1813, she performed “Parto, parto” from La Clemenza de Tito with Aloysia Lange (1759–1839), a famous singer and Mozart’s sister-in-law. Until Cordula left Zurich in 1814 she was the only female instrumentalist to be permanently employed by the Zurich Musical Society.

After Franz Joseph’s contract was not renewed, he traveled on to Baden and Aarau, Switzerland, where he accepted a new assignment together with his two younger daughters Caroline and Sophie. The departure of Cordula proved to be problematic for the existing trio. As a consequence, Caroline took over the first voice of the trio, and the responsibility for the second voice fell on the only 12-year-old Sophie. The following years must have been formative for Caroline and especially meaningful for her practical professional experience. She stepped out of the shadow of her older sister and gathered experiences as soloist, orchestral musician, music director, copyist and teacher. During the summer months, the trio traveled through Switzerland and gave concerts at numerous courts in Germany. The family only settled down again around 1814 when Franz Joseph’s health was declining. The family chose Pforzheim, Germany, where Franz Joseph was offered the lead of the municipal music organization. When he could no longer fulfill his duties, it was Caroline who filled in for him until his death in January 1819. Eventually, she handed over the position to her brother-in-law Friedrich Ostikkenberg, the second husband of Cordula. He had been a student of Louis Spohr and played together with Cordula in the Zurich Musical Society.

Caroline relocated from Pforzheim to the nearby residential city of Karlsruhe. This was the beginning of a new period in her life: Caroline’s independence. For the first time in her life she did not have to show consideration for her family, but could fully focus on her career. She prepared diligently for her first tour as a soloist, taking lessons in composition with Franz Danzi (1763–1826) and on the violin with Friedrich Ernst Fesca (1789–1826). She also taught students in piano, guitar, singing and clarinet, and gave various concerts. Danzi supported her plan to travel to Vienna, proven by a letter of recommendation from October 1821 that was likely addressed to Ignaz Ritter von Seyfried (1776–1841).7 He had been a student of Mozart, Koželuch, Albrechtsberger and von Winter, and was director, conductor and principal composer at the Theater an der Wien.8

In another letter of recommendation to his publisher Johann Anton André (1775–1842) dated from June 1822, Danzi calls Caroline Schleicher explicitly his student:

My student, Miss Karoline Schleicher highly praised the warm welcome which she had received with you, and renewed my wish to also meet your highness again after 15 years. The Potpourri for violin from my list, is the same, that my student performed in several locations with applause during her travel.9

The mentioned piece is the Potpourri for violin with orchestra, wind instruments ad libitum.10

Caroline Schleicher’s first tour as a soloist led her to numerous German cities, such as Speyer, Landau, Mannheim, Darmstadt, Offenbach, Wuerzburg, Augsburg, Munich, Passau, as far as Linz in Austria, and eventually to Vienna. She arrived in Vienna on February 10, 1822,11 and only a few days later on February 16 she performed in the Theater an der Wien in between two acts of a ballet.12 This was followed by a dedicated concert in a hall of the Musikvereinsgesellschaft (Musical Society of Vienna) on February 27,13 and a concert in the Kärtnerthor Theater on March 4.14 Eventually she gave a concert for the royal family at the Wiener Hofburg (Vienna Imperial Palace) on March 25, 1822.15

To organize her own concert in Vienna, Caroline Schleicher approached Franz Xaver Mozart (1791–1844) who resided in Vienna at that time. He referred her to Johann Ernst Krähmer, imperial-royal oboist at court and renowned csakan virtuoso (the csakan was a type of woodwind instrument popular in Vienna in the early 19th century). At this first encounter there was no “love at first sight,” at least not from Caroline’s side. Within a short time, however, they developed a mutual affection – Caroline did not only find professional musical support in Ernst Krähmer, but also her partner for life. Only half a year after this first encounter, the couple married on September 19, 1822, in the Vienna Stephansdom (St. Stephen’s Cathedral, Vienna). As witnesses present were Franz Xaver Mozart and August Mittag, imperial-royal bassoonist and long-time friend of Ernst Krähmer.16

In the following years, the couple went on numerous concert tours in the Austrian crownlands, Germany, Switzerland, and even as far as Kiev (Russia). Also there is evidence of an annual concert in Vienna, documented by the critic Eduard Hanslick in the following way: “[The couple Krähmer] was in its versatility odd enough; Ernst Krähmer played the oboe and the czakan, his wife (née Schleicher) played the violin and clarinet; they were persistent annual concert-giving musicians.”17

From the beginning the couple had developed its own performance scheme: Whenever possible they performed together and both Ernst and Caroline played two solo instruments each. While Ernst performed with the oboe and the csakan, Caroline played the clarinet and violin. Ernst Krähmer was not only one of the most renowned csakan players but also composed csakan methods and compositions for this then-modern instrument. Many of those are still in use today (for recorder).

Caroline Schleicher already had a well-developed network prior to the marriage with Ernst Krähmer. Together, however, the couple quickly advanced to be an integral part of the Viennese and international musical scene of those years. There is evidence of personal relationships and acquaintances with instrument makers like the piano builder Conrad Graf (1782–1851) and the woodwind instrument makers Johann Ziegler (1794/95–1858) in Vienna and Franz Schoellnast (1775–1844) in Presburg/Bratislava.18 The couple counted among their friends composers such as Danzi, Beethoven, Franz Xaver Mozart, Johann Georg Naegeli in Zurich and musicians like Henriette Sontag.

Unlike most female musicians of this time, Caroline did not allow her marriage to put an end to her career. She continued to perform in public and went on concert tours, even though she gave birth to 10 children during her 15 years of marriage. On January 16, 1837, when Ernst Krähmer died at the age of only 42, Caroline remained behind with five young children. The youngest child, Emil, was then only 4 years old.

Due to this personal emergency situation, Caroline reduced her public appearances and concert tours. Probably she was forced to intensify her teaching activities which left her with little opportunity for her own practice. Besides her own children, Caroline also gave piano lessons to children of aristocratic families, including Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach, a famous author who mentioned her strict piano teacher in her Kindheitserinnerungen.19

Despite adverse conditions, Caroline continued to perform in public until the age of 62. Even then she impressed the audience, as stated by the critic of the Augsburger Anzeigenblatt in 1856:

The concert of the famous Viennese clarinet player Mrs. Karoline Krähmer, which took place on May 20 of this month in the Pompeian Hall of the Drei Mohren for a distinguished audience, offered initially by the perfect play of this master, high enjoyment of art. The phantasy of her motives from The Prophet, later the Potpourri were played by Mrs. Krähmer with rare virtuosy and exceptional softness of the tone on the clarinet and cheering applause followed these accomplishments.20

Research has revealed that Caroline Schleicher-Krähmer died in Vienna in April 1873 at the age of 79. Two of her sons, Ernst and Emil, also went on to become professional musicians. While Emil had an appointment as cellist at the Theater Wiesbaden (Germany), Ernst was initially working as a cellist in Graz (Austria), and later also as a composer and music director. Eventually, he taught at a high school in Munich (Germany), where he died in 1913.

Caroline Schleicher-Krähmer was considered an exceptional talent from her early youth. The clarinet was always her favorite instrument; she made rapid progress and soon mastered it in an outstanding way. She possessed an excellent technique. In particular her warm tone and the ability to fade a tone from and to silence, is highlighted in almost all reviews. She was compared to the male clarinet players of her time, such as Hermstedt and Baermann.

Furthermore, she also mastered the violin and piano on a professional level and played the guitar. In those days it was typical for musicians to play several instruments. It was, however, unusual that a woman mastered such a multitude of instruments on such a high level. She was a composer, copyist and music director, went on concert tours against all social conventions, and performed in public with two instruments that were considered inappropriate for women. Caroline was not the first woman working as a professional musician. Her older sister Cordula also played the clarinet on the highest level. But in contrast to her, Caroline strived for an international career as solo clarinet player.

Endnotes

1 Deutsche Biographie: www.deutsche-biographie.de/sfz11872.html, (April 23, 2019).

2 Zürcherisches Wochen-Blatt, No. 62 (August 4 and 8, 1808).

3 Zentralbibliothek Zürich, AMG Archiv, Sign.: IV A1, A1, p. 582.

4 Stadtarchiv Zürich, Eheregister der katholischen Gemeinde Zürich 1809–1863, Sign.: VIII C.118, Vol. 1.

5 see Zentralbibliothek Zürich, Concert Protokoll der Allgemeinen Musikgesellschaft Zürich von 1811–1830.

6 Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Empfehlungsschreiben Franz Danzi, (October 12, 1821), Sign.: Autogr. 51/13-2 and Pechstaedt, Volkmar: Franz Danzi. Briefwechsel (1785–1826), (Schneider 1997), p. 203.

7 see Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart (MGG), Vol. 15, col. 653.

8 Pechstaedt, Volkmar: Franz Danzi. p. 207.

9 Pechstaedt, Volkmar: Franz Danzi. p. 209.

10 Wiener Zeitung, (February 13, 1822).

11 Leipziger Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung (AMZ), XXIV, No. 14, col. 226.

12 Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde Wien, Programmzettel, (February 27, 1821).

13 AMZ, XXIV, No. 19, col. 305.

14 Staatsbibliothek Berlin Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Programmzettel, (March 25,1822), Sign.: M. 1936.789.

15 St. Stephan Wien, Trauungsbuch 1821–1823, Sign.: 02-085a.

16 Österreichische Revue, Vol. 5, p. 172.

17 Marianne Betz: Ernst Krähmer. Porträt eines Musikers. In: Travers & Controvers, (Moeck Verlag 1992), p. 128.

18 Ebner-Eschenbach, Marie von: Meine Kinderjahre. In: Autobiographische Schriften I, ed. by Christa Maria Schmidt, Max Niemeyer, (Tübingen, 1989), pp. 39.

19 Augsburger Anzeigenblatt, (May 24, 1856).

20 Neue Speyerer Zeitung, No. 36 (March 24, 1821).

About the Writer

Dr. Nicola Buckenmaier studied instrumental education for clarinet and piano at the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna where she also completed her Ph.D. studies in music sociology. For the past 14 years, her research has centered around the life and work of Caroline Schleicher-Krähmer. At the moment, Nicola is writing the first comprehensive biography about this extraordinary woman of the 19th century. For more information and updates on this project, visit www.carolineschleicher.com.

Comments are closed.