Originally published in The Clarinet 48/3 (June 2021). Printed copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

RUDOLPH DUNBAR: A Striking Example of His Musical Period

by Antoine T. Clark

All photos are courtesy of Rudolph Dunbar Papers, James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

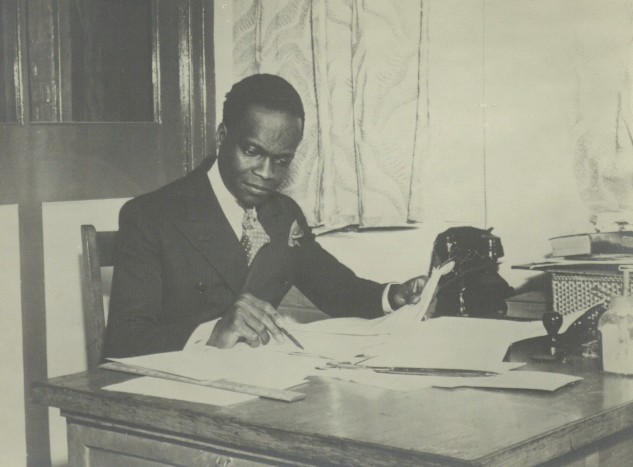

Rudolph Dunbar during the time of his studies at the Military Academy of British Guiana

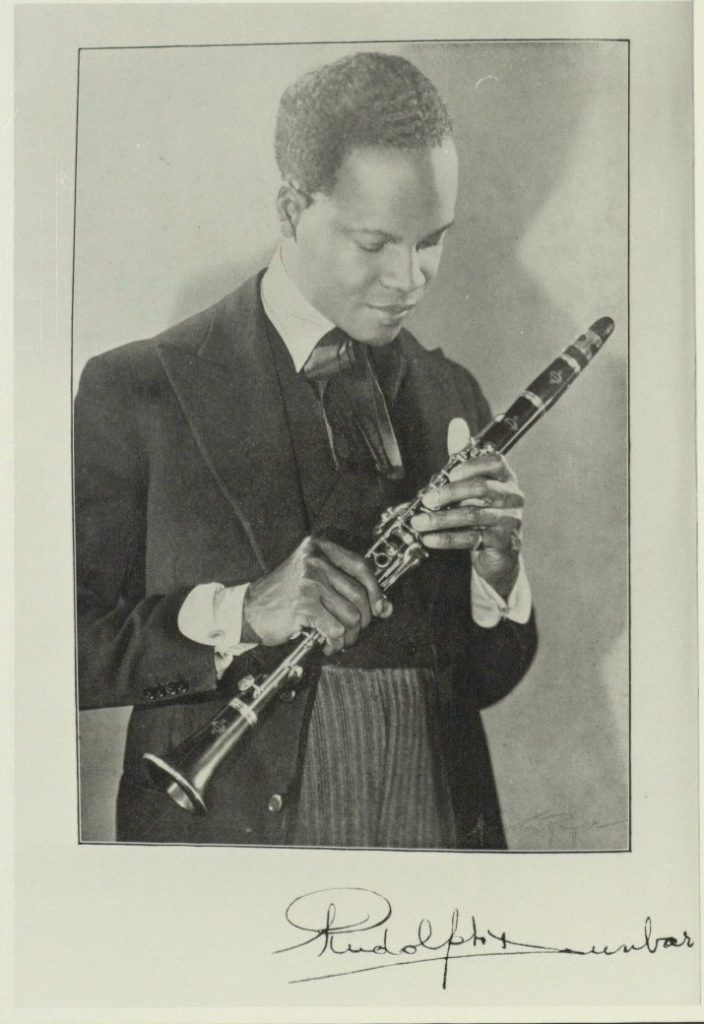

Rudolph Dunbar (1899-1988) was a virtuoso clarinetist, jazz musician, teacher, orchestral conductor, music critic and journalist. While his life and esteemed accomplishments have received renewed attention in recent years, scholarship often emphasizes his place in history as a pioneering orchestral conductor. Notably, Dunbar became the first Black man to conduct the Berlin Philharmonic. Before shifting his attention to journalism and later orchestral conducting, he enjoyed a career as a jazz musician, a virtuoso classical clarinetist, and founder of the Rudolph Dunbar School of Clarinet. While it is impossible to appreciate Dunbar’s story without paying homage to his versatile talents, his activities as a clarinetist and teacher deserve focus.

In Dunbar’s obituary published by The Guardian, his friend C.L.R. James, a West Indian cultural historian and political activist, offered a tribute that encapsulated Dunbar’s versatile career:

Dunbar was a striking example of his musical period. He was first of all a master of popular music – jazz – but he always insisted, and to me in particular, of the importance of classical music. His distinguished work must be seen in relation to the strong prejudice against coloured classical artists.1

C.L.R. James’s description of Dunbar as a “striking example of his musical period” succinctly highlights the varied artistic paths and interests in race relations pursued by Dunbar, who lived during the significant social, cultural and political change of the 20th century. As a musician that performed within jazz and classical circles, he became accustomed to living and working in different social worlds – the cultural and political elite within Europe, and his West Indian heritage. The constant struggle to reconcile his place and status within classical music dominated his life after his historic debut with the Berlin Philharmonic.

WEST INDIES to NEW YORK to PARIS

Rudolph Dunbar, the son of a pharmacist, was born on April 5, 1899, in Nabacalis, British Guiana (present-day Guyana, in South America). His birth year is uncertain since Dunbar gave various dates throughout his career. Danish Immigration Office records and different ship passenger lists show the date mentioned above.2 As a young boy, Dunbar was fascinated with music. He loved to listen to the British Guiana Militia Band perform. At these performances, Dunbar heard band transcriptions of works by Wagner and Elgar.3 At the age of 14, he joined the British Guiana Militia Band as an apprenticed clarinetist, studying with Sergeant Major Edward Arden Carter. SGM Carter, an awardee of the Medal of the Civil Division of the Order of the British Empire for meritorious service, was born in Barbados in 1883. He moved to British Guiana when he was 11 and joined the British Guiana Militia Band when he was 13.4

As a clarinetist within the militia band’s rigid structure, the young Dunbar’s talent was unmistakable.5 After serving five years in the band, he moved to Barbados and performed for a brief stint as a member of a police band.6 In 1919, Dunbar moved to New York City to pursue his formal education in music, studying clarinet, piano and composition at the Institute of Musical Art of Columbia University (now the Juilliard School). Dunbar’s decision to pursue his musical dreams did not come without some protest from his father: “Son, you’re a Black boy, born of a Black woman, and you’re going to see black days. You will want to be a musician, son, but you’ll fight your battles if you study law!”7 Dunbar would later in life understand this ominous warning by his father and indeed would see “black days,” but for now, his dream to involve himself in the creation and the interpretation of classical music was a strong attraction to an exciting adventure waiting for him.

While a student at the Institute of Musical Art, Dunbar became involved with the Harlem jazz scene to pay for his studies.8 He was also a member of the short-lived Harlem Symphony Orchestra conducted by E. Gilbert Anderson. In this group, he performed alongside such musical talents as Fletcher Henderson (piano) and the celebrated African American composer William Grant Still (oboe).9 It is through this collaboration that Dunbar developed a lifelong friendship with William Grant Still. Later in his career as a conductor, Dunbar championed many of Still’s compositions – most notably, the Afro-American Symphony, which he conducted with the Berlin Philharmonic in 1945 and with orchestras throughout Europe.

Some sources point to Dunbar traveling to Europe in 1924 to perform with Will Vodery’s Plantation Orchestra and the Broadway musical Dixie to Broadway, featuring the acclaimed African American singer Florence Mills.10 However, this claim seems to be spurious for two reasons. First, there is no record of Florence Mills performing this Broadway musical in Europe. The show ran at the Broadhurst Theatre from October 29, 1924, to January 1925, in New York.11 Second, it appears that Dunbar did not leave New York until after he graduated from the Institute of Musical Art in 1924. However, it is a fact that he performed with Will Vodery’s Plantation Orchestra in Dixie to Broadway at the Broadhurst Theatre.12

While living in Paris beginning in 1925, Dunbar reconnected with the Plantation Orchestra and performed on clarinet and saxophone for C. B. Cochran’s Blackbirds (1926) revue, which traveled to London via France during 1926-1927. In Britain, the show ran at the London Pavilion for 200 performances before closing in mid-October 1927.13 Dunbar and the Plantation Orchestra recorded four numbers from the revue on December 1, 1926: Arabella’s Wedding Day, For Baby and Me, Silver Rose and Smiling Joe.14 These 1926 recordings of Dunbar with the Plantation Orchestra are on YouTube.15

It was not uncommon for members of the show to depart from time to time. Their replacements had to be of African descent, which would have offered Dunbar the perfect opportunity to join the show while living in Paris.16 Another condition made it possible for Dunbar to avail his jazz clarinet and saxophone expertise in the revue. In the 1920s, U.S. musicians in touring Black revues and troupes received restrictions on work permits due to Britain’s “color bar” legislation. These visa or work permit restrictions theoretically did not apply to West Indian musicians who were imperial subjects.17

STUDIES IN EUROPE and THE PARISIAN STAGE

After moving to Paris in May 1925, Dunbar pursued his postgraduate studies with some of Europe’s leading musical minds. He studied clarinet with Louis Cahuzac, composition with Paul Vidal and conducting with Philippe Gaubert in Paris. In Vienna, he studied conducting with Felix Weingartner, music director of the Vienna Philharmonic from 1908 to 1927. Two years after making the Parisian capital his home, Dunbar enrolled in the Sorbonne (now the University of Paris) to study philosophy and journalism in 1927. While pursuing his classical music training and his studies at the Sorbonne, Dunbar played in jazz bands throughout Europe as he had in the U.S.18 In Paris, in the mid-1920s, Dunbar as a pit orchestra musician reportedly played for Josephine Baker, and in Rome, performed alongside clarinetist Sidney Bechet.19

In 1929, his studies at the Sorbonne ended when his father passed away unexpectedly. That year, Dunbar found himself in Leipzig. Presumably, this would have been the time that he was studying music in that city. It is unclear who Dunbar’s teacher was, or the musical discipline studied. Still, he did not stay long due to the Negrophobia perpetrated by the young Nazi party and the general atmosphere of racism sweeping Germany.20

Rudolph Dunbar as a student in Vienna, giving a talk about jazz versus classical music

Dunbar returned to Paris, and in 1930 garnered high praise from the French press for a series of clarinet recitals given that year. The Revue Internationale de Musique et de Danse (1927-1931), a journal that focused on Parisian cultural life, compiled some of the reviews. An article from that journal dated April 19, 1930, featured one of the two recitals:21

-

- Rudolph Dunbar, Negro clarinetist, well known in Paris music circles, delighted a large audience at the Salle D’Iena in that city, recently, playing Chopin and Weber. Mr. Dunbar possesses a thorough knowledge of his instrument and plays with a brilliant technic and unusual musical understanding. His playing was one of the rarest treats heard in Paris for some time… He was loudly acclaimed by his enthusiastic listeners, and the French papers recorded the following criticisms:

A sensational attraction was presented last Friday at the Salle D’Iena. W. Rudolph Dunbar, Negro clarinetist, charmed the audience by his exceptional talent, his brilliant technic and an unusually pure and charming tone. – Echo de Paris.

The colored clarinetist, W. Rudolph Dunbar, has just made his debut with great success. He is a sincere artist, who possesses a talent complete and remarkable. This happy debut is the forerunner of a brilliant future.

– Le Journal.

It was a real success which greeted the presentation in Paris of the colored clarinetist W. Rudolph Dunbar. A very pure tone, a musical and brilliant style, are the characteristics of this remarkable artist who certainly will be talked about within the musical world, and will go far in his career on the concert platform. – La Liberte.

- Rudolph Dunbar, Negro clarinetist, made his debut last Friday with great success. He is a serious virtuoso, and an accomplished musician. He charmed a numerous audience which applauded him heartily. – L’Intransigeant.

Rudolph Dunbar at the Selmer factory in Paris

Dunbar presented another recital on November 19, 1930, at the Salle Chopin Pleyel, and it was “probably the first time that a recital had been given on the clarinette” at that venue.22 His artistic triumphs on these various Parisian stages received the attention of Claude Debussy’s widow, Emma Moyse Bardac Debussy. She invited Dunbar to play for her and a select group of the Parisian cultural elite and the influential members of the Paris Conservatory sometime in 1930. The recital was a success and received glowing reviews. Maurice Dumesnil, a concert pianist, a pupil of Claude Debussy, and a Paris Conservatory employee, may have attended Dunbar’s public and private recitals. He provided the following review:

A clarinet recital is in itself a rarity but an electric and tastefully arranged programme such as Mr. Dunbar played is also uncommon. He went from Mozart to Debussy, to Weber and Chopin, all played with fine qualities, a rich fluent mechanism and excellent appreciation for the different styles of the composers. He was recalled many times.23

In addition to his well-reviewed clarinet recitals, Dunbar performed in a band with the Paris-based black American jazz violinist Leon Abbey. The band traveled to London in 1930.24

SUCCESSES in 1930s LONDON

In the summer of 1931, Dunbar moved to London, which would remain his

home until his death in 1988. During this time in England, he experienced the most fruitful moments in his career and those “black days” and “battles” that his father forewarned when Dunbar first embarked on his musical journey. For the next 15 years or so, Dunbar would experience a crescendo of successful accomplishments that set him up to be a leading figure in the world of classical music.

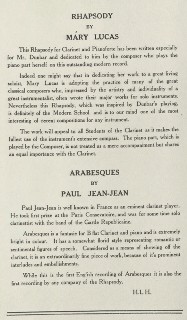

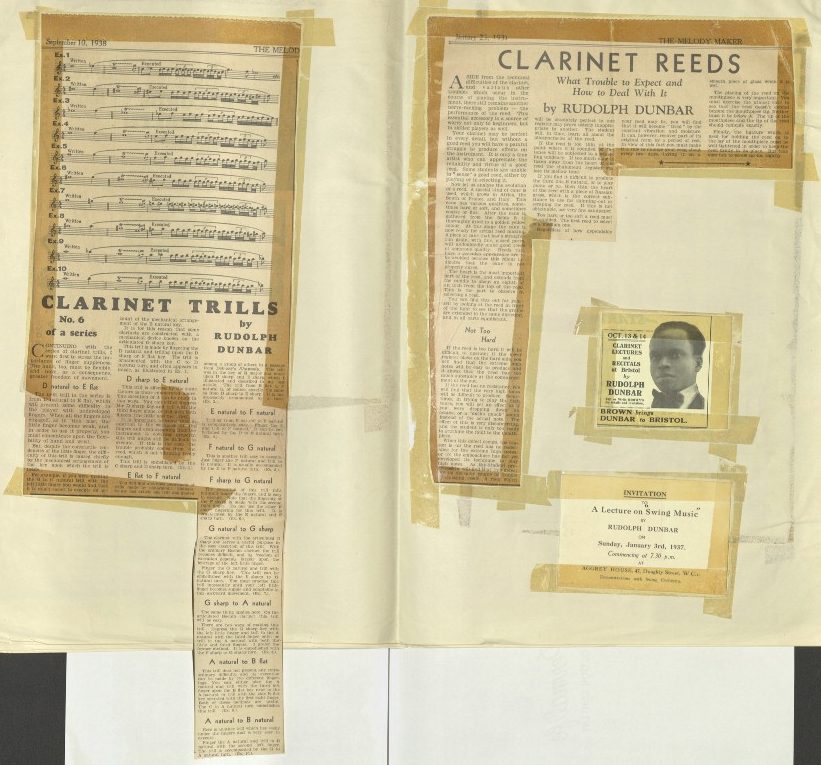

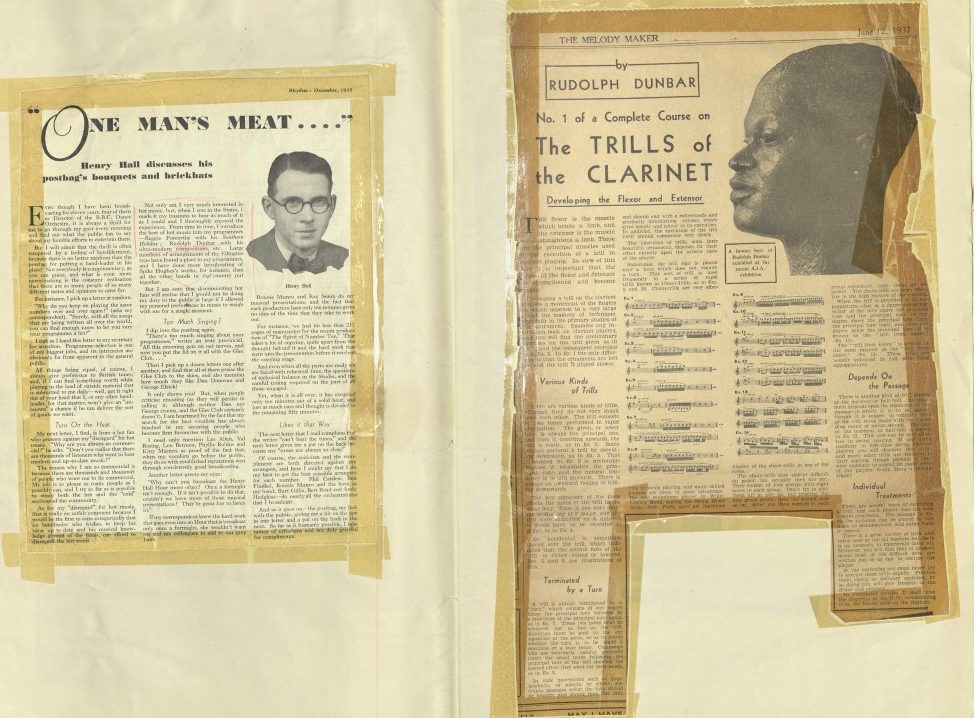

Rudolph Dunbar reviewing one of his compositions

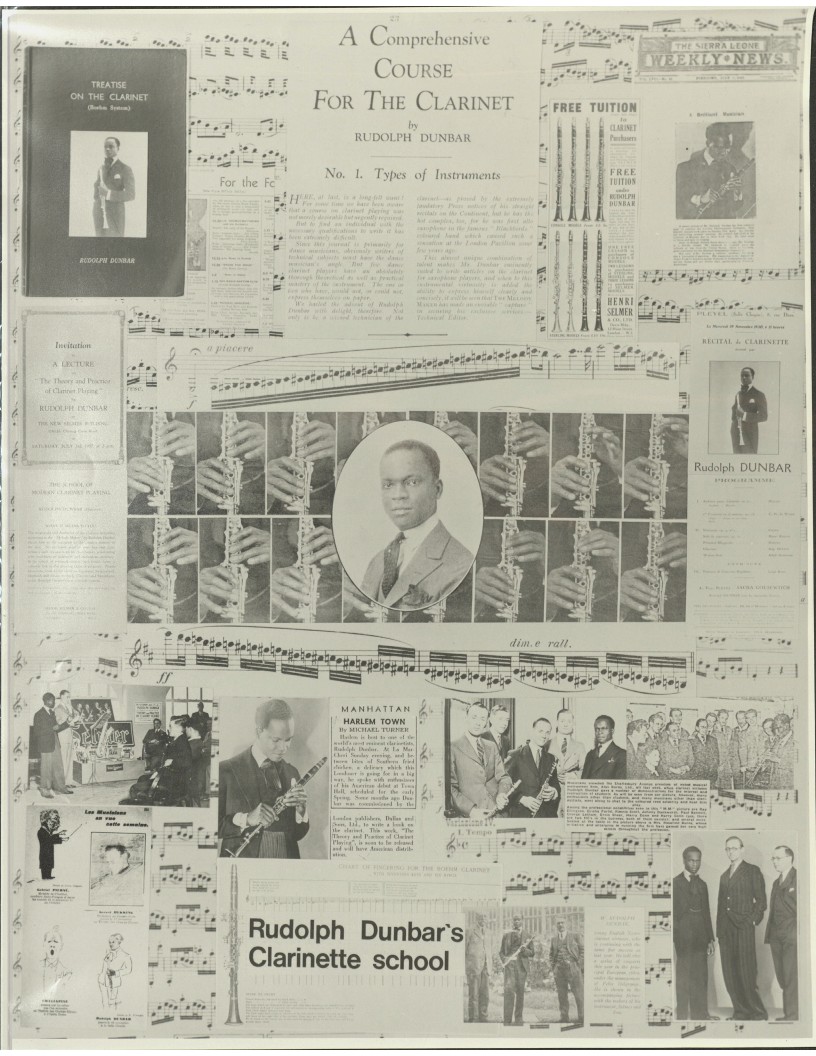

Dunbar’s first success was obtaining a position as a columnist and technical expert on the clarinet for the Melody Maker. Founded in 1926, the Melody Maker was a British “weekly magazine-newspaper for all who are directly or indirectly interested in the production of light and popular music.”25 Dunbar’s relationship with the magazine would last from 1931 to 1938. His articles appeared periodically in the journal and offered instruction on a wide range of topics related to the instrument. In his first article, “A Comprehensive Course for the Clarinet No. 1 – Types of Instruments,” Dunbar wrote that it was not “a course on legitimate clarinet playing, but a series of lessons for dance band saxophone players who wish to ‘double’ the clarinet without the hope or intention of becoming a virtuoso of the instrument.” He explained to saxophone players that they should not be afraid to approach the instrument

and that the course would help them

learn the clarinet.26

The Melody Maker editorial board was ecstatic about Dunbar’s new role as a columnist. In August 1931, the magazine published the article “A Clarinet Virtuoso,” introducing Dunbar as a “unique celebrity” and listing his accomplishments as a clarinet recitalist on the Continent. It also quoted some of the French press’s comments about his clarinet playing and listed his repertoire – “Concerto de Weber” and the “First Rhapsodie” of Debussy. The article further recalled Dunbar’s performance with the Blackbirds revue that caused a sensation at the London Pavilion a few years back. It reminded readers that he was the “hot first alto!” in the band and praised his versatility, calling him a “highbrow clarinet virtuoso doubling hot alto!”27

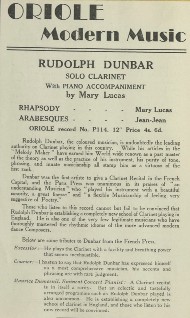

In the 1930s, Dunbar and the English pianist and composer Mary Lucas performed many recitals and recorded at least two professional recordings.28 Jacques Levy produced one recording on the Oriole label at Rosslyn House at 94/98 Regent Street, London. One can assume that the duo recorded the album sometime after 1931 and before 1937 because Levy’s recording studio was at the Rosslyn House address between those dates.29 An advertisement for the recording lists Paul Jeanjean’s Arabesques and Mary Lucas’s composition, Complainte et Rapsodie for clarinet and piano. Further information in the ad describes Dunbar as “undoubtedly the leading authority on Clarinet playing in this country” and “one of the very few legitimate musicians who have thoroughly mastered the rhythmic idioms of the more advanced modern dance composers.”

The copy in the ad references his articles in the Melody Maker and quotes tributes given by the French press when he was in Paris.30 The Dunbar-Lucas Duo’s second recording featured Lucas’s Lament for Clarinet and Piano (1938) on the Octacros Records label.31

It is worth mentioning that Dunbar may have recorded Debussy’s Première rhapsodie circa 1931. Whether this recording was on a professional label is not clear. The West Indian trumpeter Leslie Thompson, living in London and playing in the show Cavalcade (1931), spoke in a November 1983 interview of meeting Dunbar. In this interview, he referenced that Dunbar had a recording of “Debussy’s Clarinet Concerto” that he had sent to a musical director working with Cavalcade to obtain a position in the show’s orchestra.32

THE DUNBAR SCHOOL of CLARINET

Advertisement for the first Oriole Records release by Rudolph Dunbar and composer/pianist Mary Lucas

Dunbar founded the Dunbar School of Clarinet in the latter part of 1931, and it attracted students from various parts of Europe, South Africa and India.33 In January of 1932, the Melody Maker published an article promoting the school by listing many of Dunbar’s accomplishments within jazz and classical genres and his education at the Institute of Musical Art. It also stressed that Dunbar’s school offered courses for the clarinetist and the saxophonist who wished to study the indispensable rhythmic African polyphonic style.34 As a successful master teacher of classical and jazz genres and techniques for the clarinet and saxophone, Dunbar’s reputation grew throughout the 1930s.

Dunbar founded the Dunbar School of Clarinet in the latter part of 1931, and it attracted students from various parts of Europe, South Africa and India.33 In January of 1932, the Melody Maker published an article promoting the school by listing many of Dunbar’s accomplishments within jazz and classical genres and his education at the Institute of Musical Art. It also stressed that Dunbar’s school offered courses for the clarinetist and the saxophonist who wished to study the indispensable rhythmic African polyphonic style.34 As a successful master teacher of classical and jazz genres and techniques for the clarinet and saxophone, Dunbar’s reputation grew throughout the 1930s.

By 1939, the fruits of his labor brought about the publication of his successful Treatise on the Clarinet (Boehm System). The treatise compiled the many lessons he wrote for the Melody Maker from 1931-1938, and it remained in print through ten editions. Acknowledgments in the book expressed his gratitude to his professors at the Institute of Musical Art, who made his artistic career possible. He thanked the students at Oxford, Cambridge and Eton College, who showed interest in his Melody Maker articles and praised Louis Cahuzac’s skills as a clarinet teacher. An introductory section recounts the modern Boehm clarinet’s history and the clarinet’s development dating back to 1699. The treatise provides a fingering chart and 25 lessons covering the rudiments of music, care of the clarinet, reeds, breathing, embouchure, scales, technical finger development, etudes and other topics.35

VARIED ARTISTIC ABILITIES

Dunbar with pupils of the Rudolph Dunbar Clarinet School

Dunbar’s varied artistic abilities were not limited to being a jazz musician, virtuoso clarinetist and teacher. He was also a jazz bandleader, composer, journalist and conductor. The latter designation brought him international attention. In the 1930s, Dunbar led two jazz groups: the All-British Coloured Band and the Harlem Knights.36 The former was the first “all-British coloured band to be heard over the air.”37 In 1938, Dunbar wrote the ballet score Dance of the Twenty-First Century for the Cambridge University Footlights Club, and Dunbar conducted the American premiere performance on an NBC national broadcast.38 An excerpt from the ballet score is included in his clarinet treatise. Using his journalism training, Dunbar became a correspondent of the Associated Negro Press in 1932. During World War II, he was a war correspondent for the Allied Forces and covered the Normandy invasion and liberation of Paris.

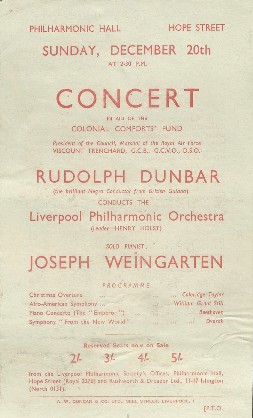

The year 1942 marked the real beginning of Dunbar’s conducting aspirations and career. He debuted with the London Philharmonic at the Royal Albert Hall, in a concert organized to raise money for the British-colored allies.39 Throughout the 1940s and ’50s, he conducted many professional orchestras, including the Liverpool Philharmonic, the National Philharmonic (Great Britain), the leading professional orchestras of France, the Berlin Philharmonic and the Hollywood Bowl. Dunbar was the first Black man to conduct orchestras in Poland and Russia.

“BLACK DAYS” and “BATTLES”

Rudolph Dunbar leading a jazz band

In the latter stage of his conducting career, Dunbar hoped for more opportunities, but unfortunately, this would not be the case. A bitter public row with the BBC left him disconcerted, disheartened and humiliated. In 1973, in a lengthy affidavit, he cited a letter written in 1957 by Maurice Johnstone, BBC Head of Music Programs, which had come into his possession. Dunbar believed that the letter disparaged him and promoted rumors that questioned his effectiveness as a conductor. He charged the BBC with mounting a racist campaign against him and thought that the influential company hindered his efforts to secure other opportunities within Britain, ruining his career as a conductor.40

CONCLUSION

In the shadow of his early triumphs breaking barriers as a virtuoso clarinetist and international conductor, Dunbar continued his career as a respected journalist covering international affairs, advocating for racial justice and writing about Black artists. Throughout the 1970s, he documented the Independence Day celebrations of African and Caribbean countries emancipated from British colonial rule. He remained a champion for the causes of West Indians and Blacks throughout the world by devoting his later years to the political fight against racism. He once stated that “the success I have achieved through sacrifice and struggle is not for myself, but for all the colored people.”41 Dunbar continued his long career as a musician and a journalist until his death in London, England, on June 10, 1988.

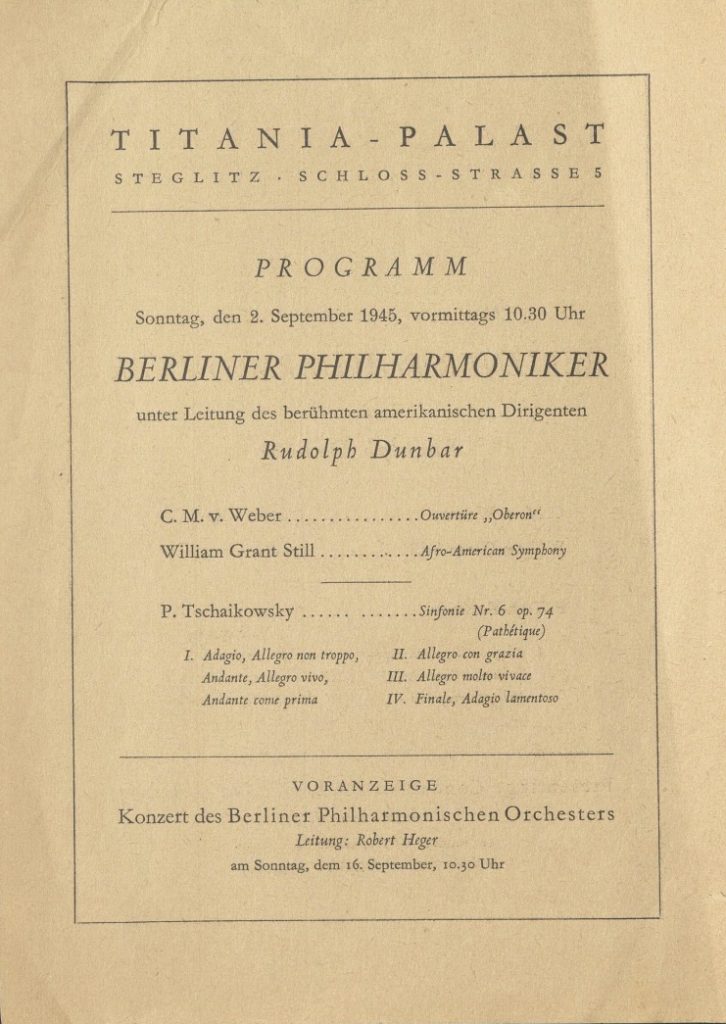

Concert programs from the Berlin Philharmonic and Liverpool Philharmonic, conducted by Rudolph Dunbar

Endnotes

1 Obituary: Rudolph Dunbar, “A Conductor’s Baton in His Knapsack.” The Guardian, July 7, 1988.

2 Rodreguez King-Dorset, Black Classical Musicians and Composers, 1500-2000 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2019), 116.

3 Dhanpaul Narine, “Rudolph Dunbar – A Musician for the Ages,” Guyanese Online Guyana and World News and news from the Guyanese Diaspora, https://guyaneseonline.net/2015/03/08/rudolph-dunbar-a-musician-for-the-ages-by-dr-dhanpaul-narine/ (accessed February 3, 2021).

4 Vibert C. Cambridge, The Musical Life in Guyana: History and Politics of Controlling Creativity (n.p.: University Press of Mississippi, 2015), under “Public Spectacles: 1931-1940,” www.google.com/books/edition/Musical_Life_in_Guyana/gRARCgAAQBAJ?kptab=overview&gbpv=1 (accessed February 3, 2021).

5 Narine, “Rudolph Dunbar.”

6 Veronica Chincoli, “Black Music Styles as Vehicles for Transnational and Trans-Racial Exchange: Perceptions of Blackness in the Music Scenes of London and Paris (1920s-1950s),” ZapruderWorld: An International Journal for the History of Social Conflict, https://zapruderworld.org/journal/past-volumes/volume-4/black-music-styles-as-vehicles-for-transnational-and-trans-racial-exchange-perceptions-of-blackness-in-the-music-scenes-of-london-and-paris-1920s-1950s/#easy-footnote-13-188 (accessed February 3, 2021).

7 Eileen Southern, “W. Rudolph Dunbar: Pioneering Orchestra Conductor,” The Black Perspective in Music, Vol. 9, No. 2 (Autumn, 1981): 215.

8 Chincoli, “Black Music Styles.”

9 Judith Anne Still, Michael J. Dabrishus, and Carolyn L. Quin, William Grant Still: A Bio-Bibliography (Westport, CT: Geenwood Press, 1996), 21.

10 Dominique-René De Lerman and Jonas Westove, “Dunbar, W. Rudolph,” in Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-1002284249 (accessed February 4, 2021).

11 Alphonso Hawkins, “The Harlem Showcase Toward a Definition,” Studies in Popular Culture, Vol. 23, No. 2 (October 2000): 46.

12 Eileen Southern, Biographical Dictionary of Afro-American and African Musicians (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press), 117.

13 Howard Rye and Jeffrey Green, “Black Musical Internationalism in England in the 1920s,” Black Music Research Journal, Vol 15, No. 1 (Spring 1995): 103-104.

14 The Plantation Orchestra, Discogs, www.discogs.com/artist/1681653-The-Plantation-Orchestra (accessed February 6, 2021).

15 Arabella’s Wedding Day – The Plantation Orchestra, C.B Cochran’s “Black-Birds” Revue – Columbia 4238, https://youtu.be/8G2cLeGWZuU, For Baby and Me – The Plantation Orchestra, C. B. Cochran’s “Black-Birds” Revue – Columbia 4238, https://youtu.be/ENK54mmc3Lc, Silver Rose, C.B. Cochran’s “Blackbirds Revue” – The Plantation Orchestra. Columbia 4185, 1926, https://youtu.be/FyqqYjVNANI, Smiling Joe – The Plantation Orchestra, from C.B. Cochran’s Blackbirds Revue of 1926. Columbia 4185, https://youtu.be/m3YIwCXeW14 (accessed February 6, 2021).

16 Rye and Green, 103-104.

17 Jason Toynbee, “Race, History, and Black British Jazz,” Black Music Research Journal, Vol. 33, No. 1 (Spring, 2013): 6-7.

18 Chincoli, “Black Music Styles.”

19 Alyn Shipton, “Rudolph Dunbar,” Independent, July 27, 1988.

20 Dominique-René De Lerman, “Rudolph, Conductor: On Black Classical Music,” The Afro American, June 24, 1978.

21 Southern, “W. Rudolph Dunbar: Pioneering Orchestra Conductor,” 195.

22 Ibid., 195.

23 Ibid., 197.

24 John Cowley, “London is the Place: Caribbean Music in the Context of Empire 1900-60,” ed. Paul Oliver, Black Music in Britain: Essays on the Afro Asian Contribution to Popular Music, (Milton Keynes, England: Open University Press, 1990), pp. 57-76, https://sas-space.sas.ac.uk/2945/1/LITP3.pdf (accessed February 4, 2021).

25 The Melody Maker Letterhead, Rudolph Dunbar Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, JWJ MSS 174 Box 1 f. 3.

26 Chincoli, “Black Music Styles.”

27 Southern, “W. Rudolph Dunbar: Pioneering Orchestra Conductor,” 196.

28 Michael Thomas’s Website, http://www.mgthomas.co.uk/Records/LabelPages/Octacros.htm (accessed February 4, 2021).

29 Levy’s Sound Studios, www.discogs.com/label/554284-Levys-Sound-Studios (accessed February 6, 2021).

30 Southern, “W. Rudolph Dunbar: Pioneering Orchestra Conductor,” 197.

31 Mary Lucas, Wikivisually, https://wikivisually.com/wiki/Mary_Lucas (accessed February 4, 2021).

32 Jeffrey Green and Leslie Thompson, “Trumpet Player from the West Indies,” The Black Perspective in Music, Vol. 12, No.1 (Spring, 1984): 115-117.

33 Alyn Shipton, “Rudolph Dunbar,” Independent, July 27, 1988.

34 Chincoli, “Black Music Styles.”

35 Rudolph Dunbar, Treatise on the Clarinet (Boehm System), (England, 1939: John E. Dallas & Sons LTD.), 1-141.

36 John Cowley, “Cultural ‘Fusions’: Aspects of British West Indian Music in the USA and Britain 1918-1951,” Popular Music, Vol. 5, Continuity and Change (1985): 88.

37 Southern, “W. Rudolph Dunbar: Pioneering Orchestra Conductor,” 196.

38 Ibid., 195.

39 Ibid., 198.

40 Affidavit, Rudolph Dunbar Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, JWJ MSS 174 Box 2 f. 37.

41 “Conductor’s Life Parallels Alger’s: Rudolph Dunbar Came Up Hard Way; Now Tops Field,” The Afro-American, February 1, 1947.

About the Writer

Antoine T. Clark holds degrees in music education, clarinet performance, and orchestral conducting from Virginia Commonwealth University, the University of Cincinnati-College Conservatory of Music and The Ohio State University. He is currently an instructor of music at Kenyon College, the Ohio Northern University and the Ohio Wesleyan University, where he teaches clarinet, saxophone, chamber music and university orchestras. Previous teachers include Charles West, Ronald de Kant, Theodore Oien and James Pyne. Clark has performed as the principal clarinet with the Dearborn Symphony and the Ash Lawn Opera (Charlottesville Opera). He is currently an associate member of the Columbus Symphony Orchestra (Ohio), assistant conductor of the Chicago Sinfonietta, and music director of the McConnell Arts Center Chamber Orchestra and the Northern Ohio Youth Orchestra-Philharmonia Orchestra.

Antoine T. Clark holds degrees in music education, clarinet performance, and orchestral conducting from Virginia Commonwealth University, the University of Cincinnati-College Conservatory of Music and The Ohio State University. He is currently an instructor of music at Kenyon College, the Ohio Northern University and the Ohio Wesleyan University, where he teaches clarinet, saxophone, chamber music and university orchestras. Previous teachers include Charles West, Ronald de Kant, Theodore Oien and James Pyne. Clark has performed as the principal clarinet with the Dearborn Symphony and the Ash Lawn Opera (Charlottesville Opera). He is currently an associate member of the Columbus Symphony Orchestra (Ohio), assistant conductor of the Chicago Sinfonietta, and music director of the McConnell Arts Center Chamber Orchestra and the Northern Ohio Youth Orchestra-Philharmonia Orchestra.

Recordings

Interview with Rudolph Dunbar: RTBF Belgium, 1962.

Transcription and translation of the spoken text by Mary Jane Cowles -Professor Emerita of French Kenyon College

https://euscreen.eu/item.html?id=EUS_B96758DCD67749BBAB21228C397C5BC8

[Any introductory question by the interviewer is not included in the video. Rudolph Dunbar’s answers are preceded by “RD”. The interviewer’s questions are noted as “RTBF”. Since Dunbar is not a native speaker of French, there are a few problems with syntax in his

answers. I have tried to make his answers understandable. A transcription of the original, with some syntactical adjustments, is included below.]

RD: I studied music in Paris, Leipzig, and Vienna.

RTBF: And after your studies, where did you begin your career as a conductor?

RD: In London. I gave a concert in 1955.

RTBF: And since then?

RD: Oh, I’ve gone…since then I have concerts in Paris, in Berlin, in Yugoslavia, in Poland, everywhere on the continent.

RTBF: And your last concert?

RD: My last concert was in Havana, a few weeks ago.

RTBF: So, you have just returned.

RD: Yes.

RTBF: But how is it that you haven’t played really since ’55, at Festival Hall, for example.

RD: [brief laugh] I don’t, you see, because… I can’t, because they know that I’m getting very well known. Even still, they are afraid that I’m becoming too popular. Do you understand? Because of that, there is a campaign against me in London, against me, everywhere. They

even write abroad against me… because the English don’t like competition.

*****

[Transcription of the original]

RD : J’ai fait mes études musicales à Paris, et à Leipzig et à Vienne.

RTBF : Et après ces études, votre carrière de chef d’orchestre, vous l’avez commencé où cela ?

RD : A Londres, j’ai [eu] un concert en 1955.

RTBF : Et depuis lors ?

RD : Oh, je vais…depuis j’ai des concerts à Paris à Berlin en Yougoslavie, en Pologne, un partout sur le continent.

RTBF : Et votre dernier concert ?

RD : Mon dernier concert c’était à Havana, il y a quelques semaines passées.

RTBF : Vous venez donc de rentrer…

RD : Oui.

RTBF : Mais comment se fait-il que vous n’avez jamais joué disons depuis 55 … au Festival Hall par exemple.

RD : [Ha-ha] Je ne vais pas, comprenez-vous ?…parce que… Je ne peux pas, parce qu’ils [savent] que je deviens trop connu. Encore, ils [ont] peur que je devienne trop populaire. Comprenez-vous ? A cause de cela, [on] fait campagne à Londres contre moi, contre moi, partout. Ils même écrivent [à l’] étranger contre moi. Parce que les Anglais, ils n’aiment pas

la compétition.

Additional Images

Comments are closed.