Originally published in The Clarinet 50/1 (December 2022).

Printed copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

Reprints from Early Years of The Clarinet

Over the next four issues, we’ll take a look back at notable articles from earlier issues of The Clarinet, along with photos from The Clarinet archives and commentary from today’s clarinetists. This edition includes a humorous (and still very relevant) article on reeds by Leon Russianoff, and a collection of excerpts from bass clarinet articles by Edward Palanker, Josef Horák, and Harry Sparnaay.

ALL YOU WANTED TO KNOW ABOUT THE BASS CLARINET AND HAVE BEEN AFRAID TO ASK

This was the first article about bass clarinet published in The Clarinet, appearing in vol. 2 no. 4 (August 1975). At the time, Edward Palanker was bass clarinetist in the Baltimore Symphony, from which he retired in 2012 after 50 years.

by Edward S. Palanker

I decided to write this article after experiencing many misconceptions, both as a teacher and performer, as to the proper approach to the bass clarinet. Most of my bass clarinet students are either doublers that want a few “hints” or clarinetists that want to learn the bass, usually in two or three easy lessons. That’s the first big mistake; thinking that a clarinet or saxophone player can simply learn the bass clarinet. The bass clarinet is neither a clarinet nor a saxophone. Although there are many similarities, it is as individual as a flute or bassoon. I teach and perform on both instruments and consider myself a clarinetist and a bass clarinetist because I’ve taken the time and effort to learn and study both instruments as if each were my major and continue to treat them as equals.

One of the largest problems confronting the beginning bass player is the third octave, especially high G, A, and B. These notes take very special care, but most often I’ve found the problems to be mechanical. The slightest leak, and I emphasize the slightest, especially on an automatic double octave instrument, can cause trouble. Unless the coordination between both octave keys is working perfectly, it will leak and cause delayed attacks and squeaks. Any leak in the upper joint will be disastrous, especially for the inexperienced player and has been the largest factor in the discouragement of playing the bass clarinet.

The third octave does indeed have more resistance than the lower two and must be approached very carefully and slowly. There is a certain feeling necessary for playing this register that is not found on the clarinet or saxophone. It’s almost a delayed action which can only be mastered by practicing soft attacks, long tones, and easy tonguing exercises until one develops that “feeling.” There is no short cut.

One of the most common errors in the early stages of switching to the bass is due to the ease in which it takes to get a nice, big, vibrant tone in the low register, especially with a soft reed and closed mouthpiece. But what happens above the throat tones? A small, choked, often squally sound is the result. What’s needed is a relatively freeblowing mouthpiece with a medium opening that will enable the player to use a reed that has body and that will not close up when supported up high. I began on a Selmer C star and now play a double star. I’ve found both of these to enable the student to produce a good, rich tone in all registers with comfort and control.

The combination of reed to mouthpiece goes hand in hand with the choice of mouthpiece. Generally, the more open the mouthpiece the softer the reed, and the more closed the mouthpiece the harder the reed. This being a very personal choice, one can find dozens of possibilities. …

The angle of the mouthpiece is a very important point, generally overlooked by the novice. It is individual and should be somewhat experimented with to find the position most comfortable and beneficial. I like to get under the mouthpiece, angling my head back some but not so much as to put strain on my throat muscles. For this reason, I’m very fond of the Selmer neck design. It has a slanted upward angle and enables me to get under the mouthpiece, somewhat in between a clarinet and saxophone position. One should be flexible with the amount of mouthpiece in the mouth. Find what generally gives the best result and use that as a starting point. There are times when a bigger or smaller sound may be desired, or a reed is a bit soft or hard, or a delicate entrance may warrant more or less reed in the mouth. The bite does not have to be the same at all times.

I recommend the use of a peg on the bass either with or without a neck strap. It helps stabilize the instrument and keeps the height at a more consistent level. If you’re adding a peg to your instrument, have it attached to the bell not the body, no matter how secure it is it will work its way loose from the wood.

The hand position does not differ very much from that of the clarinet. The left hand does have to work harder to get over the height of the G sharp key. I recommend a little more flexibility in the moving of the wrist and even the forearm in fast passages around that section of the instrument.

Fingerings differ very little from the clarinet to bass clarinet. The extreme high C sharp and above require the use of the half hole. C sharp and D work with or without the half hole, anything above D the half hole becomes necessary. High F sharp is fingered half hole plus middle finger, High G add E flat side key R.H. or fork finger left hand. Alternate for high C# is thumb and side keys 1 & 2 R.H. (or 1 st finger left hand above), alternate for high D is overblown open G and support.

For the student that has orchestral playing in mind, there are some facts about notation they should know. First of all, one must be able to transpose from bass clarinet in A in both treble and bass clef. Some examples are Ravel’s La Valse and Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde. Now there are two basic ways for notating, the German and the French, but because there are so many exceptions to these two ways, we should consider there to be three ways, the third being a kind of mix and match.

The French is the easiest. It is written the same as clarinet and fingered as one would a clarinet part. It just sounds an octave lower. Second line G in treble clef is played open G sounding low G, only the treble clef is used. This is how all band music is notated and most contemporary orchestral music. Some standard examples are Ravel’s Daphnis and Chloe, Gershwin’s American in Paris, and Strauss’s Till Eulenspiegel. The German is a bit more complex although its principle is simple. It is written in the octave that it sounds, like a bassoon or cello, and is written in both treble and bass clef. If the desired note is open G on the bass clarinet, it is either notated as a G top space bass clef (as it sounds) or as a G written two ledger lines below the treble clef (written as it sounds) so the player must play open G to sound low G. In other words, when the bass clef goes to treble clef, one must read an octave higher than normal to compensate for sounding an octave lower. Examples are Franck’s D minor Symphony and Strauss’s Death and Transfiguration.

The third way is a combination of both, developed out of the misunderstanding of the other two. Some composers use both French and German together without informing the player what he means. Generally the writing has low parts as written in bass clef (German) and higher parts in treble as written (French). The only way to determine this is trial and error and experience. Stravinsky’s Petrushka is a prime example. He writes the same passage once in German and again in French, for no apparent reason. It should have been written either way, the same both times. He’s not alone. Many lesser known composers do it constantly.

The first three cello suites of Bach, as written, are good practice in reading bass clef as well as in flexibility. Play mordents or broken chords for double stops. Any of the standard clarinet methods work fine for bass and, keep in mind that an orchestral bass clarinet must be proficient on clarinet as well. If you’re in the market for a bass, it might be wise to consider one with a low C. There are a number of orchestral works for which it’s needed. They’re becoming fairly popular in American orchestras.

THE COURSE OF THE BASS CLARINET TO A SOLO INSTRUMENT AND THE PROBLEMS CONNECTED

WITH IT

The following is excerpted from the original article in The Clarinet 4 no. 2 (Winter 1977). Josef Horák (1931-2005) was described in the issue as a “virtuoso bass clarinetist and member of the Czechoslovakian Due Boemi.” He performed the first-ever bass clarinet recital on March 24, 1955, inspired hundreds of new works for the instrument, and became known as “the Paganini of the bass clarinet.” Horák and his wife, pianist Emma Kovárnová, played together for 42 years as Due Boemi until he passed away in 2005.

by Josef Horák

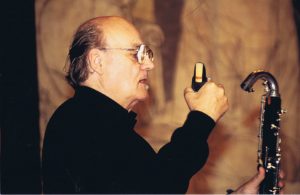

Josef Horák

The bass clarinet, being indispensable in every large orchestra of today, only very slowly achieved a foothold. … The bass clarinet was first used by Meyerbeer in The Huguenots. But above all Berlioz, Wagner, Liszt (in his Dante Symphony), Richard Strauss, and B. Smetana have given the instrument its extraordinary, characteristic tone colors. These masters used the bass clarinet primarily because of its low pitch and its mysterious and soft color, which is particularly well suited to arouse definite associations.

In the nineteenth century, the sound volume of the bass clarinet contained itself in a weak dynamic. Up to very recent times, composers and musicians were quite convinced that this instrument was not capable of an increased sound intensity.

At a later date, Webern used the bass clarinet in his chamber music very often and effectively, just the same as Stravinsky in his Le Sacre du Printemps, where he used two bass clarinets. Other composers of a more recent epoch used the instrument within the orchestra because of its low sound color. You are, of course, familiar with the use of the instrument in the motion picture industry and television when they require background music in “who-done-its,” as it can produce an atmosphere of tension.

A rule has almost crystallized that the bass clarinet plays its soli in the orchestra at the very moment when all the other instruments are silent so that it can be heard well.

For twelve years I was clarinetist at the State Philharmonic in my own country, Czechoslovakia. As so often in life, pure chance played a decisive role. When one of my colleagues (the bass clarinetist in the orchestra) fell ill, I had to function as a substitute. Since that occasion, the principal conductor of the orchestra never wanted to have another bass clarinetist. Since that first close contact with the instrument it occurred to me after some time that the limited role of the instrument is really not necessary. I immediately fell in love with the bass clarinet and I regretted that this beautiful instrument was used to such a limited extent. I sensed extensive and variable ranges of expressions. By purposeful technique of breathing and a modified mouthpiece, I have tried from the beginning to increase the sound intensity over the whole range of the instrument. After a time I succeeded. Then the problem arose of the higher and highest compass—in address and intonation. I succeeded eventually, due to a new technique of address, breathing, and fingering combination. Today on my instrument I use a sound range of almost four and a half octaves. I am convinced that this is the more natural way to solve these problems as musicians and that it is not necessary to improve the bass clarinet in this direction by means of technical constructions. By saying this I will certainly not express the opinion that the instrument could not be improved by a versatile constructor with understanding for the bass clarinet, modifying a few mechanical details. For instance, one often hears a metallic noise when trilling with the long keys. Also there is the possibility of damage to the mechanism of the register key. These and similar problems occur with frequent usage even with the best makes.

Josef Horák and his wife, pianist Emma Kovárnová

My first experiments within the realm of virtuoso technique of playing the bass clarinet could not remain in the category of exhibitionism. I intended to apply it to solo compositions. Composer colleagues from the orchestra wrote the first pieces for me, inspired by my extensions of the possibilities of the bass clarinet. These pieces again brought forth new problems which I tried to solve.

The transitions between the various registers were too obvious. Even instrumentation manuals pointed this out to composers. By composing for a soloist, this difficulty had to be relinquished.

To overcome this difficulty, the idea of sound production of singers, as well as diaphragm breathing, helped me. Composers also employed leaps and bounds over the whole range of register as if it were a normal clarinet. Considering the very long air column of the bass clarinet, qualitative differences become apparent. To master these passages, it is my opinion that a considerably sensitive touch is necessary. This sensitive touch is also important when playing larger interval steps legato at high pitch.

It was also necessary to master fast technical runs over the whole range of the bass clarinet, which created some difficulties, particularly at high pitch. It took quite some time before composers realized what can be done with the bass clarinet. Before writing his first suite for me, the practician, experimenter, and quarter-tone composer, Professor Haba, wrote to me asking whether the bass clarinet can play only slow sixteenth notes a la Bach, or also fast ones as in Mozart.

I have already spoken about the necessary increased sound intensity. It is obvious that a solo instrument has to be properly heard, and this is particularly true when you think of a solo for bass clarinet and orchestra. And since the middle register is relatively weak, somewhat fallow and faded (a fact which is quoted in all instrumentation manuals) I was pleased when I succeeded by means of diaphragm prop-up to eliminate this disadvantage. Already in my repertoire are some solos with orchestra accompaniment. I have played these with various orchestras and the sound of the bass clarinet was always very definite. At the beginning of his concerto, Reiner demanded a sound which was fanfare-like over a rather large range.

Also very effective are impressive accents similar to bells, used very often in different variations over the whole range of the bass clarinet and also in connection with pianissimo echo sounds. There we are already dealing with techniques of play which are demanded by the composers in the New Music.

The composers of the New Music asked me for expressive passages to provide the corresponding tonal expressiveness in their works. I demonstrated a few variations and thus I arrived at a kind of shriek, which is really an alienated sound combined with trilling. These shrieking quavers have already been christened by composers for some years as “Clamor Horakiensis” or “Horák’s clamor.” These clamors come out best at the higher pitches of the bass clarinet. Very often I combine them also with a glissando, creating siren-like associations. The possibilities of playing in this way are really quite variable.

The opposite of these loud sounds is a manner of playing for which I have selected the term “zeffiroso.” It should sound even quieter than any pianissimo, rather like sotto voce. This technique of playing is possible on the bass clarinet practically over the whole range of register. …

Split tones or double tones, as they are sometimes called, are used on the bass clarinet in the same manner as other woodwind instruments in the New Music. It is my opinion that it is more appropriate if the composers indicate this manner of playing only symbolically and do not demand precise sounds. It is my personal experience that by playing the same fingering sequence on different bass clarinets, different double sounds are produced. …

As is also most likely the case in the USA, in Europe there are discussions being waged today regarding whether or not a clarinet and a bass clarinet should be played with vibrato. For instance, all Czechoslovakian orchestras today already play with vibrato. On the other hand, the clarinet players in German or Austrian orchestras play without vibrato. I am of the opinion that one should be led by the spirit of the composition which one is playing. …

The bass clarinet as a solo instrument offers, of course, many more possibilities than those I have briefly mentioned. In my opinion it is of particular importance to have an easy and elastic embouchure. If this embouchure is too firm and rigid, there is always the inherent danger that the upper pitches will lack the full and round quality. Besides this is the fact that this upper pitch as a rule will be a trifle too low. Also, producing the notes G and A above the staff is particularly difficult on the bass clarinet if the embouchure is too firm and inflexible. Very often the sound makes a somersault, producing an awful noise not unlike the sound one would expect from stepping on an unsuspecting goose’s neck. At the beginning I was invariably surprised when critics from various countries wrote that during my recital on the bass clarinet they heard a number of instruments. As I love the “sound ideal” of the mellow clarinet of Bohemia, I am most happy if my bass clarinet does not sound too cutting or penetrating. As a boy I really desired to play the cello. The tonal quality of this instrument fascinates me to this very day. By playing the bass clarinet, I frequently image the sound of a string instrument. I try then to imitate the singing quality. Once in Berlin after one of my concerts, a photographer said to me that he thought he was hearing a cello being played in the concert hall as he listened behind the door. I was happy to hear that. I have the conviction, which I share with many of my colleagues of the clarinet, that woodwind instruments should have something in common with the smoothness and softness of the strings.

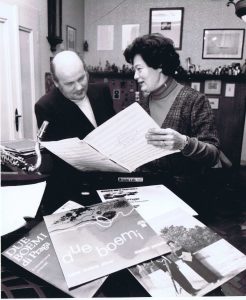

Horák and Kovárnová performing as Due Boemi

An interesting problem in constructing a bass clarinet is in regard to lowest tones. In Western Europe, only so-called “short bass clarinets” are built in series. These instruments have a range to low DÌ. If you want a “long bass clarinet”, with range to low B, one must have it custom-made.

Although composers of symphonic works very often demand the low B, primarily short bass clarinets are being built. In my country, all orchestras have long bass clarinets. Long bass clarinets are taken for granted in Czechoslovakia, in contrast to other European countries. … There are cases where composers are not satisfied with the extensive width of register of the bass clarinet. A young Czechoslovakian composer requested a low A from me. I at first told him that this is not feasible. But then I remembered bassoonists who, in the operetta Polenblut, stuck rolled up scores into their instruments to get lower notes. I also pushed a paper roll into the corpus and, low and behold, low A was born. Later on, I had to play low G, using an even longer tube. But I think that the range of the bass clarinet should suffice most composers. …

My first bass clarinet recital was in 1955. It was the first full evening solo recital of the bass clarinet in the world. At that time I played only arrangements, of course, by Vanhal, Wagner, Fibich, and others. With these arrangements I stood before the task to convince the world of music that the bass clarinet, which was used up to now only for limited scope within the symphonic orchestra, is an instrument with much greater and hitherto unused expressional extent and with undreamt-of possibilities. But at the same time the composers had to be convinced that I needed their help to provide a fitting, musically interesting, and expressionally manifold repertoire for this instrument. One of the first well-known composers who helped me was Paul Hindemith. He authorized his bassoon sonata anno 1938 and his trio for bass viol, heckelphone, and piano for my bass clarinet. When he visited Prague in 1961 and I played the sonata for him, he said that he can imagine it only with difficulty to be played on the bassoon. …

I encountered difficulties in holding my instrument while playing compositions newly written for me. As you know, the bass clarinet player is seated within the orchestra so that the instrument is placed perpendicularly between the feet on the floor. This positioning has proved itself satisfactory within the orchestra, as the technical demands are not great. When I had to play virtuoso passages with my left hand during a solo, it quite often happened that due to the pressure of the thumb (mainly when playing c3 and other finger positions in the vicinity) the instrument slipped away. This happened also when I had fixed the bass clarinet to a cord around my neck. To overcome this difficulty, which hampered the technique of playing with the left hand and the register key, I tried to shift the center of gravity of the bass clarinet. I support the lowest part of the instrument on the instep of the right foot a little bit in front of the heel. The right foot has to be placed on the ground along its whole length. To get the proper equilibrium in this type of position I place the left foot slightly forward. Not only I but also my students had the best experiences with this playing position.

Besides this, I have modified the metal support for the thumb of the right hand in such a manner that it forms a hook similar to the saxophone. There the thumb fits in well and is fixed. I find this particularly important for the inclined position of the instrument. In playing difficult passages one experiences a feeling of security. I have found it very essential if one wants to play the bass clarinet lightly and loosely when seated that the instrument should have a fixed center of gravity. ….

There are bass clarinet players who stand when playing solo. Perhaps this position is of advantage to jazz musicians. The instrument gets closer to the microphone. I find playing while standing not advantageous with music where a noble, beautiful, and soft tone plays a decisive part. The bass clarinet has then a much smaller volume as the rostrum does not resonate along with it. … Standing during a solo has another disadvantage: the hands, mainly the right, cannot remain sufficiently loose.

Although while standing, the bass clarinet is suspended on a neck cord, the right hand still has a supporting function and this creates certain problems during technical play. Because of the effort, the hand gets stiff and cramped easily. While sitting, however, the right hand can remain loose and relaxed. ….

The problems which I have touched upon here are only a handful of those which I have encountered during my 20 years with the solo bass clarinet, and over which I have pondered. Maybe 20 years is a long space of time, but what are 20 years when you consider them in relation to a new solo instrument? I am absolutely convinced that the bass clarinet, an instrument with extensive and rich possibilities of expression, has a promising and important future and will play still a greater role among the other solo instruments. The activities and achievements of my pupils and successors are already fully confirming my views.

MUSIC FOR THE BASS CLARINET—PART IV:

AN INTERVIEW WITH HARRY SPARNAAY

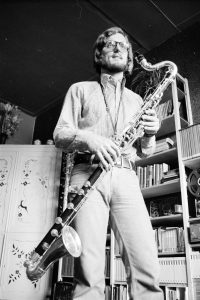

These excerpts are from an interview with Harry Sparnaay (1944-2017)—originally printed in The Clarinet 7 no. 4 (Summer 1980)—by Norman Heim, then professor of clarinet at the University of Maryland, and doctoral student Charles Stier. Sparnaay’s innumerable accomplishments included serving as professor of bass clarinet and contemporary music at the Conservatory of Amsterdam for 35 years, premiering hundreds of new works for bass clarinet, and publishing his book “The Bass Clarinet: A Personal History” (2011).

by Norman Heim

Sparnaay in 1975

HS: To be honest, I started [playing bass clarinet] by accident because I wanted to play saxophone at the Conservatory. At that time (in the sixties) saxophone was not allowed to be studied at the Amsterdam Conservatory—the name Conservatory meaning “conservative.” It was played only in dark cellars, smoking cellars. It’s really true, really! So I came to the Conservatory when I was fifteen years old, and I played on tenor saxophone and they were completely amazed to listen to me in a piece by Charlie Parker and they asked me, “What do you want?” and I said, “Yes, I want to study saxophone.” And they told me that it is not possible. “When you want to study saxophone, it’s perhaps better for you to first study clarinet and it’s also good for your saxophone technique. And I was a young man and I said, “O.K. Perhaps this is the way; you will know it—you are the people who have to know it.” So I started to study clarinet. And more and more I liked the clarinet, more than the saxophone. So I didn’t play saxophone any more, and I played clarinet. But I missed something in the sound of the clarinet from what I had in the sound of the tenor saxophone. So, I had all my degrees for clarinet and suddenly my teacher came with a bass clarinet, really suddenly, and he said, “I bought myself a bass clarinet.” And I heard the tone and said, “O.K., this instrument I want to play.” Of course, this is not a tenor saxophone but this is more like a saxophone than clarinet. So I bought myself a bass clarinet and I started, little by little, and then after a year I could get that same sound out and from that moment I was thoroughly intent to (what’s the name), do what I have on my mind to do. So I said,” No, I want to specialize in bass clarinet” and I stopped playing clarinet. From that moment I haven’t played clarinet at all. …

NH: So you didn’t study with anybody on bass clarinet?

HS: My teacher gave me some help and suggestions.

NH: So in other words you developed all the ideas on how to do it and perhaps fingerings …

HS: On fingerings and the register, yes. And now it has developed so far that for the upper register I have for each note at least four fingerings so I can use them slurred. Sometimes one fingering is better than another. …

CS: How did you go about establishing yourself; when did you decide to play bass clarinet as a bass clarinet soloist? And then how did you accomplish this?

HS: I felt when I had the instrument at home, it wasn’t only an orchestral instrument because I felt that there was so much richness in the tone quality so the possibility to use the bass clarinet in the orchestra was not considered. When you listen carefully to orchestras and consider what the bass clarinet is doing or you don’t hear it at all.

NH: How about in Wagner? You hear some in Wagner.

HS: And Strauss. But those composers are the only ones where the bass clarinet can be heard. … So I thought it best to take the bass clarinet out of the orchestra, and to play solos like the normal clarinet and the bassoon.

CS: So that you really started seeking commissions for yourself?

HS: Yes, I perhaps wrote at least twenty or thirty letters a week to composers.

NH: Do you ever play any of the ensemble music by Schoenberg, Berg, or Webern where the bass clarinet is scored?

HS: Of course, of course, for many years.

NH: They’re all nice pieces.

HS: And Pierrot Lunaire, Ooh! Ooh! And sometimes I hope that the younger persons are writing such good pieces.

NH: What I think is phenomenal with the bass clarinet is that for so many years, back maybe fifty or two hundred, as long as we have had the bass clarinet, we have had only orchestral literature, hardly anything for solo bass clarinet such as a concerto or anything; all of a sudden in the last perhaps fifteen years we have a repertoire of five hundred or six hundred works, original works, no transcriptions. In addition, so many are so very difficult. And there’s nothing in between. We may have some of the beginning literature for youngsters who are beginning to play but then there’s nothing in the middle.

HS: That is so complicated.

NH: The difficult literature is so complicated that it’s too bad that we don’t have something in between.

HS: It’s very bad. I have only perhaps ten pieces from all that repertoire that are of average difficulty. … I think the best pieces now are really very difficult, not only technically but also for the amateur. Ferneyhough pieces, marvelous pieces, but after those pieces you should have a holiday for at least two weeks. You understand? …

NH: Do you think it’s better to start on another instrument and then play bass clarinet or should you start right out on bass clarinet when you begin playing? …

HS: I think it’s very good if possible to start on bass clarinet, but the risk for the student playing only bass clarinet is big to get in an orchestra or something like that. And I never will tell my students to do it the same way as I did. I always say, “O.K., bass clarinet is good but keep the clarinet in mind or your flute or your saxophone. Don’t forget it.” Because I have had the luck. I succeeded in my concept of bass clarinet playing but I think always also I succeeded because I have a kind of mentality, you understand?

NH: Sure. … Would you encourage youngsters to study bass clarinet?

HS: Yes, yes.

NH: The reason I ask is because in this country, if a young person plays clarinet, it is the weakest players that are taken off of clarinet and put on alto, bass and contrabass clarinet, and that defeats the whole purpose because you never have anyone who is musically gifted to play one of the lower instruments. That’s a real problem. … What do you think is the biggest problem of playing the bass clarinet?

HS: Tonguing.

NH: Why? Do you feel it’s because of the placement of the tongue or the reed is in the wrong place in the mouth, or ….

HS: No. No, I think it’s only a difficulty with the construction of the instrument.

NH: The way it’s built. Is there too much resistance when you’re tonguing?

HS: Yes. For example, I have played bass clarinet for a long time, but when I have to play B”, in the second register, softly—staccato, I am sitting on my chair, like “Is it going to go?” Because that’s risky, not loud, not soft.

NH: So it’s the use of the tongue.

HS: Incidentally, I started with my students the Uhl Etudes. They are beautiful. And I tell them, “You can forget all the slurs and study all the etudes staccato short, not fast, because fast is easier. Play isolated staccato notes for practice—it is a science to play each note “bup!” Because when you play “bup” it’s like the beginning of Sorcerer’s Apprentice by Dukas. The beginning is G and when you tell the student to play only that G, like in Dukas, he plays “KCCH!” not “Bup.”

NH: Right. And it takes him an hour to learn to play one note. I know.

HS: And that’s why it is a little bit frustrating for advanced clarinet players, when they study with me, since they have already graduated from the Conservatory. They have their diplomas for clarinet and then they are coming to me for the appendix, yes? The appendix, it is called? And they have all their papers, saying clarinet soloist, and then they come to me and I say, “O.K., blow a G.” Splat! and then again, splat! And that’s very difficult, and sometimes they say, after studying many months, “No, I can’t play bass clarinet; I can play clarinet, and it frustrates me very much to start again as a new student on bass clarinet.” …

BASS CLARINET COMMENTARY

It is simply remarkable how far the bass clarinet has come since the 1970s. It’s no longer an anomaly, and there no longer seems to be a need to provide an introduction and raison d’être (an undercurrent I observed in these early articles). Quite the contrary; young musicians now start on bass clarinets (gasp!), universities now offer bass clarinet majors, and instrument ergonomics and intonation have improved significantly. It’s pretty remarkable—I can’t think of another acoustic instrument that’s seen so much progress during this time period.

– Michael Lowenstern

I recall receiving a lot of thanks for writing the article and clearing up some misconceptions about approaching the bass clarinet and how it’s notated in orchestral music. At the time I wrote this article the bass clarinet was basically a large ensemble instrument that band directors would ask their weakest students to play. In the last several decades it has not only became the first instrument of choice by many young students but has also become recognized as an instrument of great varying color and technical ability in its use for solo and chamber music.

– Edward Palanker ([email protected], eddiesclarinet.com)

There is no doubt that the bass clarinet has recently become a very important instrument. The changing role of the instrument in the orchestra, in chamber music, and as a solo instrument during the 20th century is a fact. The literature for bass clarinet has quantitatively grown in the last 50-60 years and the quality of the instrument has improved, too. Players and teachers are specializing in bass clarinet and its pedagogy, and now it is not only an auxiliary instrument for the clarinetist. I would like to highlight the important role of women. Until a few years ago it was extremely difficult to see a woman as a bass clarinet soloist, and fortunately there are already many of us!

– Lara Díaz

In 1999, when I began my bass clarinet studies, I was fully aware of two things: the astonishing possibilities of the instrument and the hundreds of pieces written for it. These two things were not known even by the majority of clarinetists. Fortunately, nowadays the perception that the bass clarinet is an instrument by itself is widely shared. However, despite this, I have seen in many places that there are still certain prejudices against it when it comes to establishing a bass clarinet class. What justifies the study of an instrument? This is a question I always ask to my bass clarinet students on the first day of class. And the right answer is: the amount and quality of the repertoire written for it. We certainly have it.

– Pedro Rubio

The days of moving the weakest clarinet player in band to play bass clarinet are over; students are choosing to play bass clarinet and kicking @ss on it! The increase in solo repertoire, etude and method books, virtuosic players, and students studying bass clarinet has led to degree programs in bass clarinet specialization. We also have new music chamber groups, like the reed quintet, featuring the bass clarinet, and even orchestra, band, pop, and film music has evolved to take advantage of the instrument’s full range and technical prowess. It’s such a versatile instrument; from powerfully raucous to soothing and sensitive, the bass clarinet has arrived and become its own instrument.

– Stefanie Gardner

It is incredible how Edward Palanker’s words are still very relevant today! We have new, extremely flexible and precise instruments, which serve us really well, but we still have to fight with the same efforts to achieve a good and nice tone. Reading their articles from 1977 and 1980, I must say that I’m so thankful to Horak’s and Sparnaay’s work because they drove new generations of players into a world where the bass clarinet is totally considered as a solo instrument with its own repertoire and dignity.

– Stefano Cardo

Three major areas have changed in the bass clarinet world since I became a professional in 1974:

1) Equipment: instruments, mouthpieces, reeds, everything down to ligatures have improved drastically

2) Solo works: In 1974 Harry and Josef were known in this country only to real aficionados. Now bass clarinet is one of the favorite instruments of contemporary composers, because of range, color and dynamic capabilities. So there are an enormous amount of chamber works, solos with orchestra, and recital works available to players.

3) Number of people seriously pursuing the bass clarinet: I used to be the only one showing up at ICA annual get-togethers (before it was called ClarinetFest®) with a bass. Now I can’t believe the number of bass cases I see there. Hopefully that means that the old stigma—“Oh, they play bass, they must not be any good”—is gone.

Some things that have not changed in the orchestral bass clarinet world:

1) Sound still wins auditions. Having an interesting sound, and using it well, is mandatory to advance.

2) Audition lists are pretty much the same as they’ve always been, and tend to be made up by players who don’t actually play bass. This makes it hard for committees, made up mostly of non-clarinetists, to really understand what they are listening for.

– J. Lawrie Bloom

In the last five decades a lot of things have changed in technical problems. In fact, thanks to the collaboration of many performers with the constructors, they gradually perfected the instrument, I mean in terms of intonation and technical facility. Today, for example, we have few problems playing the third octave, rather the problems arise when we are preparing to play in the fourth one!

It is curious to hear Harry’s impressions about synthetic reeds; I am sure that if he could try them now he could change his judgment. Harry is talking about the approach to the bass clarinet that in those years was not easy both technically and especially mentally speaking—he studied practically alone, he was a pioneer! Not only because he was the one of the first to be interested to study bass clarinet and improve it technically, but with his work he changed the mentality of composers regarding the use of it.

If today we have a lot of pieces written for bass clarinet by great composers—like Luciano Berio, Iannis Xenakis, Arturo Marquez, Ennio Morricone, Arthur Gottschalk, Franco Donatoni and many others—it is thanks to Harry who believed and sought this collaboration.

– Rocco Parisi

The last five decades saw the further emancipation of the bass clarinet: more bass clarinet specialists, the growth of bass clarinet repertoire in all genres, and an expansion of documentation, educational material, and research. Despite this development, many orchestras continue to require bass clarinet candidates to only play soprano clarinet in the first round audition and request soprano clarinet repertoire—such as Spohr—and not original bass clarinet repertoire—such as Schoeck—to be played in the second round audition.

– Henri Bok

Comments are closed.