Originally published in The Clarinet 46/1 (December 2018). Printed copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

Master Class

Leonard Bernstein’s

Sonata for Clarinet and Piano

by Gary Gray

Leonard Bernstein was born on August 25, 1918, to Jennie (née Charna Resnick) and Samuel Joseph (Shmuel Yosef) Bernstein, in Lawrence, Massachusetts. Leonard Bernstein was a man of many accomplishments, but he was proudest of his own achievements as a teacher. There’s a Hebrew phrase that makes me think of my father: Torah Lishmah, he said, which means, loosely translated, “a raging thirst for knowledge.” I’m sure you’ve all had that feeling. Maybe you were researching a subject you were intensely interested in, and came across a document that went right to the heart of your thesis. Or maybe you just settled into your train seat with a big, juicy article in a magazine about your all-time favorite sports hero or movie star. Or the day after the first presidential debates, you buy all the newspapers, nearly salivating with anticipation at reading all the spin.

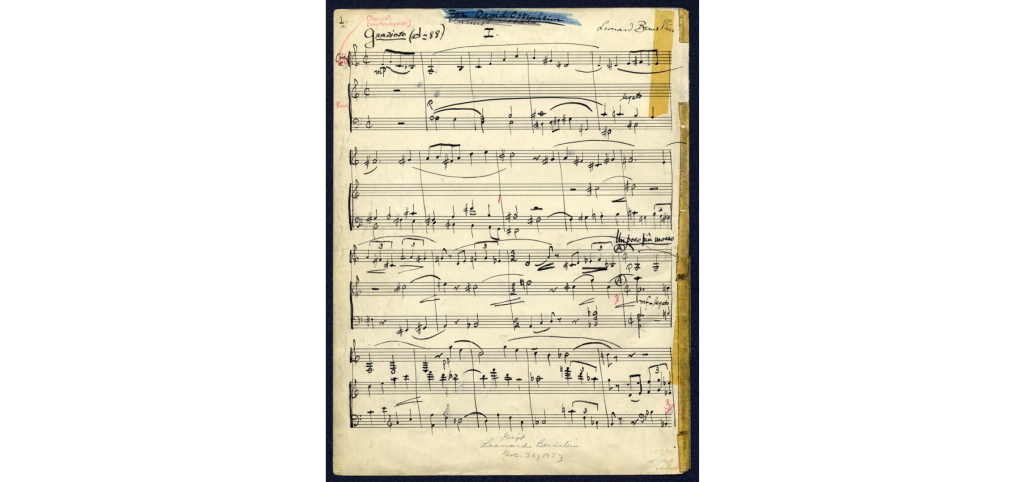

Bernstein Sonata manuscript

Bernstein just could not absorb enough information on the things that interested him. His brain was on fire with curiosity. And what he loved most was to communicate his excitement to others.

To say he was a true Renaissance man is really an understatement. Luckily for all of us, it wasn’t enough for Leonard Bernstein to compose music and conduct orchestras. He felt equally compelled to talk about music – to try and explain what made it tick, and how it made him tick; what made it good, and what made it affect us in the many different ways that it does.

There have been very few figures in the arts who have been as well-rounded as Leonard Bernstein. He wore many hats: in addition to his work as a composer, conductor, pianist – and recording artist in all three of these roles – he was also the author of numerous books and essays. He appeared in trailblazing television programs of his own writing, and was an inspiring teacher. Additionally, he delivered numerous lectures at universities and conservatories. Providing yet another aspect to his multifaceted persona, Bernstein was also involved with numerous civil liberties and humanitarian concerns throughout his life.

The list of awards Bernstein received in his lifetime is remarkable; it includes 21 honorary degrees; 13 foreign government decorations from eight countries; 13 Grammy awards out of over 30 nominations; 16 platinum/gold and international record awards; 25 television awards, including 11 Emmy awards; 44 arts awards of various natures; 23 civic awards in the form of keys to the city and state proclamations; and honorary memberships or offices in over 20 societies and orchestras, including Laureate Conductor of the New York Philharmonic (1969) and the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra (1988), and President of the London Symphony Orchestra.

The Bernstein Sonata for Clarinet and Piano is about 10 minutes in length and is divided into two movements. The first is a concise, linear Grazioso which is comprised of natural growth combined with tender lyrical reflection, with a hint of “Hindemithian” harmony, full of jazzy, rocking rhythms. The Andantino, with its walking bass and syncopation, is an exciting mix of jazz, dance and the plainsman style of Copland and Harris. Hindemith, who was the composer-in-residence at Tanglewood in 1940, subtly hinting at the influence of Copland, remarked that the Bernstein Sonata was perfection, and especially appreciated in the idyllic Tanglewood atmosphere.

The second movement begins Andantino (in 3/8 time) and moves into a fast Vivace a leggiero after a tranquil opening. This movement is predominantly in 5/8 but also changes between 3/8, 4/8 and 7/8 throughout the piece, foreshadowing Bernstein’s work in West Side Story. Later the more reflective mood of the first movement returns, with a Latin-infused bridge passage.

The premiere took place at the Institute of Modern Art in Boston, performed by David Glazer on clarinet and a then 23-year-old Leonard Bernstein on piano. The New York premiere took place a year later at the New York Public Library, with Bernstein again on piano and David Oppenheim, for whom the piece was written, on clarinet. The two later released the first recording of the work.

Now a popular piece in the clarinet repertoire, initial reviews were mixed. The Boston Globe and The Boston Herald reviewed the premiere. Though the former praised its jazz inflections, both felt the composing was stronger for the piano than for the clarinet. Many early reviews alluded to the influences of Hindemith and Copland. By the end of 1943, though, Bernstein had become a conducting star through his work with the New York Philharmonic, and subsequent reviews were more positive, especially in regard to the jazz aspects. Since then the piece has received much critical acclaim and is an important addition to the standard clarinet repertoire. Several alternative arrangements of the Sonata have appeared, including a concerto arrangement by Sid Ramin (the orchestrator of West Side Story) and a transcription for cello by Yo-Yo Ma.

Bernstein’s visit to the clarinet was not short-lived, and he later returned to composing for the clarinet in 1949, when he composed Prelude, Fugue, and Riffs for solo clarinet and jazz ensemble, dedicated to Benny Goodman.

The Sonata is important to the clarinet repertoire not only because it is by such an important and eminent 20th-century American composer, but also because it shows both the classical and jazz abilities of the clarinet. The clarinet was in need of such an addition to its previous repertoire of the Classical, Romantic and Impressionist periods such as Mozart, Brahms and Debussy. There are some jazz idioms in Gershwin’s works from 20 years earlier, and Bernstein continued this legacy.

I was attracted to the piece immediately and excited by the opportunity to perform it at live concerts and then record it for Centaur Records. As a classical clarinetist who also has had a career in jazz and film music, I really love this piece because it does not stick to traditional classical modalities but crosses the boundaries of a variety of genres, even including some Jewish and American folk themes.

This piece achieves so much emotionally in such a brief performance time – it is a play-by-play challenge. When I prepare to play this piece it awakes certain visceral emotions such as pure pleasure and renewed belief in humanity which gives me the confidence to make each performance my own while being able to enjoy and bring unique pleasure to the audience.

In my opinion the Bernstein Sonata is not really a sonata in the traditional sense of sonata form with main theme–development–recapitulation. The Bernstein Sonata is more of a rhapsody and is a through-composed piece.

Performance Recommendations

The following is my personal advice after many years of performing this piece.

Movement 1 is marked Grazioso, half note = 88. The four eighth-note pickups in the clarinet should be played slightly slower than the tempo itself in order to begin the piece soloistically and draw the audience in.

Example 1: Bernstein Sonata, Mvt. 1, page 1 of manuscript

The clarinet continues with this melody for nine bars. Note where it uses quarter-note triplets for one bar, then mixes a beat of eighth notes with one beat of quarter-note triplets.

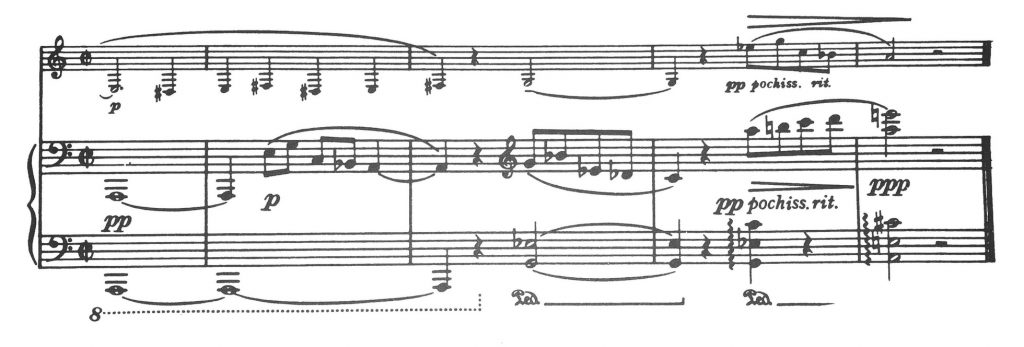

The movement continues the interplay of previous melodies as noted. Starting from letter O, I play more rubato all the way to the end of the movement where the clarinet and piano match up on the last four beats with a very romantic ritardando version of the original melody.

Example 2: Bernstein Sonata, Mvt. 1, last five bars

Movement 2 begins with an Andantino clarinet melody which is then imitated by the piano and leads to the Vivace e leggiero in 5/8 time. The clarinet has the melody through this section all the way to 13 after B where the clarinet melody illustrates Bernstein’s understanding of the clarinet’s overblowing 12ths occurring at 2 before C.

Example 3: Bernstein Sonata, Mvt. 2, two bars before C

Pick ups to the 12th bar of C utilize the clarinet’s glissando ability à la Gershwin. The embouchure must be so fluid that there is no note distinguished between the D and A. I make the contrast in this section dynamically exaggerated between loud and soft in order to exploit the soloistic extremes of the instrument. For example, the fifth bar of F can be very loud and the seventh bar very soft.

Example 4: Bernstein Sonata, Mvt. 2, first seven bars of F

Another opportunity for this extreme comes four bars after H, where two bars are very soft (piano) and two bars are subito forte. In order to exaggerate these dynamics I take more mouthpiece for the upper notes.

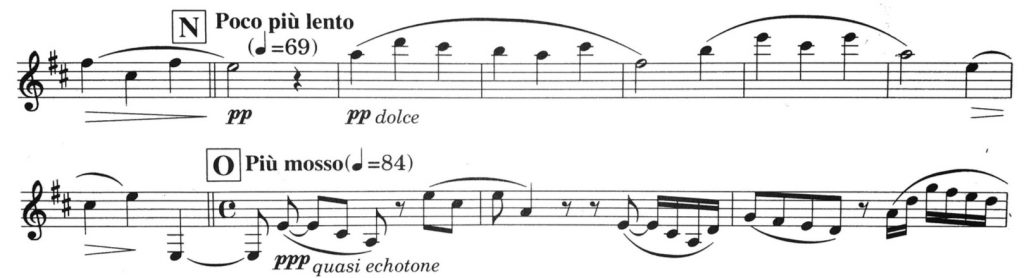

From letter N onwards to O there are places where the clarinet can achieve different tone colors. Letter N can sound more like a flute, and letter O suddenly utilizes a chalumeau-range clarinet echo tone.

Example 5: Bernstein Sonata, Mvt. 2, at N and O

The 11th to the 12th bar of P is again a glissando à la Gershwin. The piece proceeds onward in 5/8 until the end. To be successful playing this piece, it is necessary to conserve some dynamic and soloistic energy all the way to the end of the piece.

I want to point out three scales used or implied in the work: the pentatonic, blues and octatonic scales. Classical players should be knowledgeable about these scales which are part of the language of a jazz player, and another way in which the Bernstein Sonata crosses musical boundaries from classical to jazz.

When I perform this piece, especially the end part, I approach it as a jazz soloist like Benny Goodman, holding the clarinet up in a high position. Then I let the audience applaud and take my bow – a dramatic end to a dramatic piece.

About the Writer

Gary Gray is professor emeritus of UCLA’s Herb Alpert School of Music in Los Angeles, and enjoys a versatile career as a concert artist and studio musician. He was formerly the principal clarinetist of the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra and the Los Angeles Opera Orchestra. His concerto CD with the Royal Philharmonic was nominated for a Grammy award. During his long career in Hollywood he recorded more than 1000 film and television scores with composers including John Williams, Henry Mancini and Lalo Schifrin. Gray received his bachelor’s and master of music degrees from Indiana University, where he studied clarinet with Robert McGinnis and Henry Gulick. Contact him at [email protected].

Gary Gray is professor emeritus of UCLA’s Herb Alpert School of Music in Los Angeles, and enjoys a versatile career as a concert artist and studio musician. He was formerly the principal clarinetist of the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra and the Los Angeles Opera Orchestra. His concerto CD with the Royal Philharmonic was nominated for a Grammy award. During his long career in Hollywood he recorded more than 1000 film and television scores with composers including John Williams, Henry Mancini and Lalo Schifrin. Gray received his bachelor’s and master of music degrees from Indiana University, where he studied clarinet with Robert McGinnis and Henry Gulick. Contact him at [email protected].

Comments are closed.