Originally published in The Clarinet 43/4 (September 2016), this online version contains a supplemental Discography and List of Works. Printed copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

by Rachel Yoder

The groundbreaking clarinetist known as William O. “Bill” Smith turns 90 this September. A founding member of the Dave Brubeck Octet, Smith also pioneered the use of multiphonics on clarinet in the 1960s and has continued to experiment with extended techniques throughout his life. Born in Sacramento, California, he studied at Juilliard, Mills College, the University of California–Berkeley and the Paris Conservatory, and his longest teaching appointment was at the University of Washington, where he taught composition, clarinet and contemporary music for more than 30 years. He has enjoyed great success over seven decades as a composer and performer. He is still writing and performing music, most recently at a residency this summer at the Bologna Conservatory in Italy. I had the opportunity last spring to talk with Smith in his Seattle home as we looked back together on some of the highlights of his extraordinary career.

William O. Smith with two demi clarinets. Photo by Virginia Paquette

Rachel Yoder: Do you mind if we go back a few years? I know that when you were studying at Juilliard in 1945-46, you were also involved in the jazz scene in New York. So did you play classical clarinet by day and jazz clarinet by night?

William O. Smith: Well, at that period I was playing mainly tenor sax for the jazz gigs and clarinet for the classical things. My clarinet teacher at Juilliard was an old-school German who insisted that we all use crystal mouthpieces like he used, and it was a very good, very pure sound, great for Mozart and so forth – but not so great for jazz. And so most of my New York playing was clarinet for the “legit” gigs and tenor sax for the jazz. I played on 52nd Street; I was very lucky. At that time, 52nd Street was the mecca for all the great jazz players – Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Coleman Hawkins – it was an honor for me just to play on that street.

RY: So on 52nd Street, did you get to play with any of the greats at that time?

WOS: No, I had a regular gig at Kelly’s Stable with a jazz trio, the Vickie Zimmer Trio. But I could walk down the street and hear all these greats. I was a 20-year old kid from the West Coast and I was lucky to have a job! [laughter]

RY: Now, after that you went to study with Darius Milhaud at Mills College. He first came to Mills in 1940, and you were living there in Oakland at that time, right?

WOS: Yeah, but I had never heard of him.

RY: So where did you first hear of him then?

WOS: My piano teacher at Juilliard assigned me a little collection of piano pieces called The Household Muse by Milhaud, and I just fell in love with them. I thought, “This is great. I’d really like to study with this man.” And I went to the library and did some research on what he’d written, heard recordings of his, looked at some of his scores, and in my reading, discovered that he was teaching at Mills College. I hadn’t known that before. I was dissatisfied at Juilliard – it was great as an instrumentalist, because everybody practiced many hours a day and you were required to achieve a very high level of performance and that was good for me; I’d never been with players who were that good before. But in terms of composition, I didn’t really gain anything at that time. At a certain point I thought, “Well, what am I doing struggling, trying to live in New York, wanting to compose but not having the teachers I’d like? Why don’t I go back to Oakland where I’m from, and study with Darius Milhaud, one of the great composers of the world, and be in my own backyard?” And so I went to the summer session in ’45 I think, and I had not composed anything before except a little woodwind quintet that I wrote when I was 15 or 16.

RY: So what inspired you to study with Milhaud – was it his interest in jazz?

WOS: I just liked his music. Of course, I was all the more anxious to study with him when I heard that he was a jazz devotee. I remember that we had to audition to get into that summer session. There were about 25 composition students that wanted to be in Milhaud’s class, and we were all sitting on the stairs outside of his little bungalow where he taught and lived on the Mills campus. We’d go in one at a time and play our music for Milhaud and he’d listen and decide whether we were accepted. The guy before me on the stairs went in and played for Milhaud, and he had written a fugue that to me sounded like Bach. I thought “Wow, this guy can really write!” And he played perfectly. I thought, “Well, how can I compete with him? I’m strictly a fumbling piano player.” But, when he got finished performing, Milhaud said, “Well, that’s not a composition, that’s just a schoolbook fugue. Get out of here,” you know! So then I went in and I fumbled through my woodwind quintet, the opening part of it, and he said, “Oh that’s very nice, you can come into my class.” And that was one of the biggest thrills of my life, to be accepted by Milhaud into the class and have him accept my compositions, and to be on my way to being a composer, which I had always wanted to be but never had any instruction. One of the biggest compliments I ever received from Milhaud was when I had written a little piece for chorus and for instruments. Milhaud said he’d like to include it on an upcoming concert of student works. I said, “That would be wonderful, but I don’t have anybody to conduct it, we’re all involved in singing and playing in it.” And he said “Ah, well, I will conduct it.” I thought that was the most generous, wonderful thing, that this great man was going to conduct a piece I’d written as a first-year composition student. He was inspiring, not only on a musical level but on a human level. And the same could be said of Roger Sessions, actually. The next year, Milhaud was going to Paris to teach at the Paris Conservatory and he suggested I go to Cal [University of California– Berkeley] and study with Sessions. So Sessions accepted me and, again, he did a very generous thing. Here I was, a new freshman in his composition department, and I was in class studying the Schoenberg Second String Quartet. He talked a lot about Haydn’s string quartets and I thought, “Well, I’d really like to know more about Haydn’s string quartets.” I asked him whether I could take a special studies course to study Haydn’s string quartets, and he said he would like to do that but didn’t have any time in his schedule. Then he said, “Well, if you want to have lunch with me on Thursdays we could go over the Haydn quartets.” [laughs] So every Thursday we’d go over for a hamburger across the street and I would talk to him about what I’d discovered in the Haydn quartet that I’d been assigned to look at. He was a very generous man, and a very admirable person that made you think, “Well, I’d like to grow up to be like him!”

“I just have a peculiar curiosity that wants to see what are all the possible things I can do with the clarinet.”

RY: Now was that where you learned about twelve-tone composition, from Roger Sessions?

WOS: Yeah. I mean, I knew about twelve-tone music before, but I always thought of it as being too binding in terms of rules and regulations. I wanted to be free to just use what note I wanted. But “Schizophrenic Scherzo,” which is a piece I wrote for the Brubeck Octet in the mid-’40s, uses a twelve-tone row, and it was my early version of atonality.

RY: What do you remember about your time at the Paris Conservatory from 1951 to 1953?

WOS: Well, I was in Paris on the Prix de Paris, which was a prize for California composers to go to Paris for two years. The second year I was there, I arranged to study clarinet at the conservatory, and it was an interesting experience. We had a clarinet class of several clarinetists and we’d stand in a circle around our teacher, who was [Ulysses] Delécluse. He’d give us etudes and then in class we would perform the etude and be criticized. The technical proficiency of the other kids was amazing. And you know, in all things that involved technique, I think it was very beneficial for me to study at the conservatory. But in terms of musicality, it was zero. There was nothing about playing chamber music, or playing Mozart, it was just… technique. And so it was good for me and I’m glad I did it a year, but I don’t think I would’ve thrived in the conservatory environment.

RY: Where was your first teaching job?

WOS: When I got my job at USC [University of Southern California] it was my first tenure-track position. That was a pretty good job – for five years I taught there. In those times, in the late ’50s in Los Angeles, there was a lot of interest in jazz, lots of studio work and very fine musicians. And fortunately I was introduced to Lester Koenig who was the owner of Contemporary Records, and he was interested in my music. He asked if I would write a 20-minute piece for Red Norvo’s combo that we could record. LPs had just come out – this was 1955 – and so he wanted me to write a piece that would take advantage of the new format. I decided to write my Divertimento, like Mozart for a jazz group, chamber music for a jazz group. He liked that, it was successful, and after that he asked me if I’d like to write another one – a 20-minute piece featuring me on clarinet and a nine-piece group, so then I wrote the Concerto for Clarinet and Combo. He gave me the greatest musicians in LA at the time, which means in the world, as many of the jazz musicians went to LA because there was lots of work for jazz men in studios and in clubs. Contemporary Records was a life-saver for me because they recorded not only several of my jazz things, but also one or two albums of my classical music, which included my string quartet. So the bright part in my life in LA was not the university, but Contemporary Records.

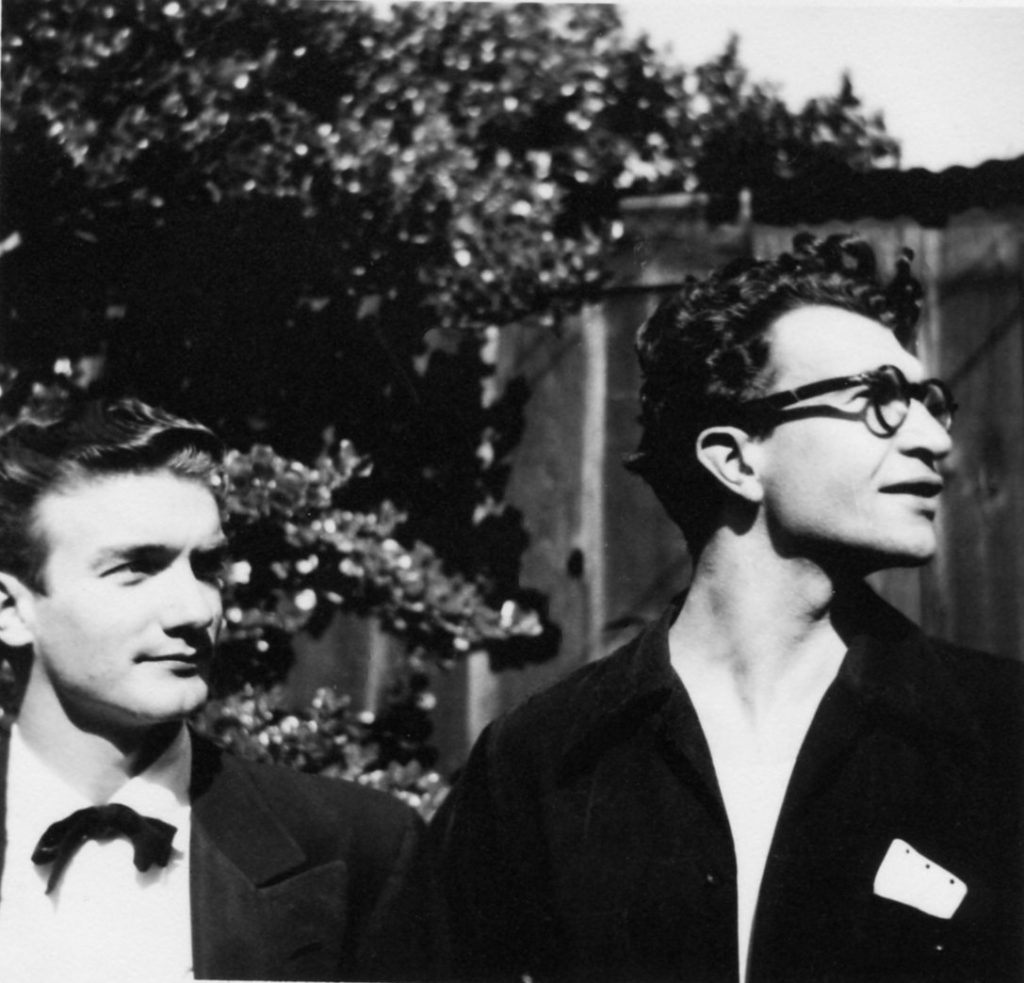

Paul Desmond (alto sax) and Bill Smith (clarinet) in 1947

RY: You’ve talked before about playing with Dave Brubeck and how that all started in the early years, but I am curious about what it was like performing with Brubeck in the later years – were you all still writing new charts, or were you mostly playing older stuff?

WOS: Well, when Dave and I first started playing together, it was in the Octet. And we all wrote for that, and it was a very good environment. I tried a lot of things, the “Schizophrenic Scherzo,” for instance. The Octet kept going off and on from the mid-’40s to the early ’50s, but it was mainly in the ’40s when we would do college concerts. We played at the University of California–Stockton, the College of the Pacific, and occasional gigs, but we were not very employable. The clubs didn’t want an eight-piece group – they wanted three or four men they had to pay – and the ballrooms wanted dance bands at that time. They’d have a 12-piece band that played for dancing. Anyway, we didn’t work a lot. We would go to play at a Chinese restaurant as the Dave Kriedt Band one week, and then get fired, and then come back the next week as the Dick Collins Octet, and then get fired…

RY: Because of the kind of music you were playing?

WOS: Oh yeah, it was considered way far out for those days.

RY: Well, then you went your separate ways for a while?

WOS: Well, no, Dave and I always saw each other as friends, and we played together occasionally when he came to town and played a concert – he’d invite me as a guest soloist often. And at a certain point, in the ’60s, he had me under contract to write and play an album a year for his quartet, and to not record jazz with any other group. I wrote the first album called The Riddle, and during the ’60s I wrote half a dozen albums for Dave. He was at a period in his career where he was very much in demand, and the record companies wanted him to do more and more. So to have me take responsibility for one recording session a year was good for him and good for me, because I’d write him 10 tunes and have them beautifully performed. And Dave and I always liked playing together.

RY: And you played with him all the way through the early 2000s, right?

WOS: Oh yeah, when he’d come to Seattle I’d play with him. For 10 years I played full time with him; in the ’80s, I played all of his concerts. I’d fly to the East Coast every weekend, just about, and then summers we’d usually do a world tour or European tour, and it was good – I had a chance to play a lot. After the ’80s, he would still invite me to play solos with his group, right up until near his death in 2012. Three or four years before his death he played a concert in Seattle and asked me to play it as a guest.

“There is a wonderful quote from Mozart where he was asked his secret to making music, and he said, ‘love, love, love.’ I feel that that’s the most important thing. If you love the music, you can make it sound musical.”

RY: I’m interested in your recent compositional work. Have you been continuing in a similar direction, or are there new ideas that you’ve become interested in?

WOS: Well, it’s sort of a summing-up of what I’ve done. I had a commission to do a piece for a New York clarinetist, Mike McGinnis. He asked me to write a piece for clarinet and nine-piece combo. He’d played my Concerto for Clarinet and Combo and wanted to have a new piece for his band, so I wrote a twelve-tone jazz piece for him, Transformations. For ClarinetFest® 2013 in Assisi, I wrote Assisi Suite for two double clarinets and bass, which I played with Paolo Ravaglia, and I also did an improvisation with my delay pedal as part of another concert. I was involved in two concerts there. One was presented by Buffet clarinets, and the other was part of the regular concert series. I should put in a good word for Buffet. I’ve been a Selmer user all of my adult life, and my fingers are really “Selmer fingers.” But I’m especially beholden to Buffet because they built a special set of double clarinets for me and Paolo, and I liked that a lot. To play double clarinet you’re playing the upper notes of the left-hand clarinet and the lower notes of the right-hand clarinet. And they made it so there’s a long octave key that you can manipulate with your right thumb, which I guess I invented with my clarinet repairman friend Scott Granlund. The tone holes on the upper joint of the right-hand clarinet are blind holes, so you don’t have to use corks.

Bill Smith and Dave Brubeck in 1948

RY: Do you have tips for performers on interpretation of your works, your classical compositions?

WOS: Well, basically the most important thing is to play it with musicality, with the feeling that it’s music. There is a wonderful quote from Mozart where he was asked his secret to making music, and he said, “love, love, love.” [chuckles] I feel that that’s the most important thing. If you love the music, you can make it sound musical. If you’re just doing it cause you’re getting paid to do it – not so easy. And the other thing I would say is that in all of my pieces, there are some measures that are really hard. I wouldn’t play in public any piece of mine unless I’d had the chance to practice it every day for a month! And so it’s a matter of playing music you love, and working your tail off to get it perfect. I think most pieces I’ve written are largely easy, but there are little thorny parts in each of them that take a lot of work. And it’s probably partly because when I wrote the pieces, when I was making up my multiphonic catalog, I thought, “Well, if I can get that multiphonic to sound once, if I work on it, I can probably get it so that I can control it and play it other times.” Fortunately, I graded [the] level of difficulty in my catalog of multiphonics and so they’re either A, which I try to use most of the time, because that means it’s easy to play; B, sort of easy to play; C, look out; and D, probably avoid it; and if it were F I would not include it. But the fact that you could get it once indicates that you can do it. And so if you practice it long enough, you can reliably repeat that one that you got.

RY: So would you say repetition is a key for mastering multiphonic technique?

WOS: Oh yeah, definitely. Just do it over and over. I think any multiphonic, if you worked on it, practiced it every day for a month, you could do it, whatever it is.

RY: What was it that interested you about multiphonics initially?

WOS: It was really to satisfy my own curiosity. I was and still am interested in exploring whatever possibilities I can think of that would broaden the clarinet’s range of sonic possibilities. I first got into multiphonics after hearing a concert by Severino Gazzelloni – a very fine Italian flutist who at that time was interested in the avant garde and worked with Luciano Berio to write the Sequenza for flute, and in it, there are some multiphonics. I heard him play at a concert in 1959 in Los Angeles and was astonished. I thought it was great – he had such command, he could go up to the double stop, the multiphonic and play it perfectly and beautifully. And I thought, if the flute can play two notes at once, maybe the clarinet can also! And so I tried and tried and tried, couldn’t get any results, and then finally I had a breakthrough where I found that just about any fingering you play on the clarinet can result in either a single note or a multiphonic. So I decided I would catalog those, and made the catalog of every fingering I could think of at that time. In 1960 I had a Guggenheim Fellowship to go to Rome, and then I had enough time that every day I could devote an hour or two to exploring every fingering I could think of, and I made myself a little card catalog.

RY: So why do you think no one else had done that before you did it?

WOS: Oh, there’s no money in it! [laughter] I just have a peculiar curiosity that wants to see what are all the possible things I can do with the clarinet. And there are quite a few other people in the world who have a similar curiosity. I write my music, I guess, for me and for them and for any other people who are interested in expanded possibilities of clarinet.

RY: So do you feel that you still have the two different personas of William O. and Bill Smith, or do you feel like they’ve come closer together over the years?

Dave Brubeck and Bill Smith in 1959, preparing to record The Riddle at Tanglewood

WOS: [Laughs] Oh, I don’t think there is any William O./Bill Smith persona – when I was recording with Contemporary Records, Lester Koenig said, “Well, we’ve got your String Quartet, we’ve got your jazz albums, and it seems pretentious to call you William O. Smith on your jazz things, and yet it sounds flippant to call your String Quartet by Bill Smith.” So it was a matter of convenience. I’ve never really had a split personality, I’m the same guy. [laughter] But I do think that I exist in two worlds. I mean, if I write a piece for jazz group, I’m writing it with my Bill Smith hat on. And as a jazz musician, as I have always been, from age 13 when I had my first band up until now, I identify and love jazz. But also, thanks to Benny Goodman actually – when I was a teenager, I heard his recordings of the Mozart Clarinet Quintet, Debussy Première Rhapsody and the Bartók Contrasts – I discovered classical music. And so now when I write, if I’m writing jazz, it’s like that’s one language that I’ve known all my life and seems natural to me; if I’m writing for string quartet, then I’m speaking another language, the language of classical music, and that seems natural to me. And in many pieces I try to blend them together. And that’s the tricky part! [laughter] But I think to have the spirit of jazz in the classical things is good, and to have the jazz well-constructed like classical music is healthy.

RY: So the last thing I would ask is, when you look back at your extraordinarily long career, what are you most proud of?

WOS: Ah, well… I guess there are two things that I’m especially proud of. One of them would be my Concerto for Clarinet and Combo, and the other is Variants for Solo Clarinet. And the one, the concerto, is influenced by classical music. The other, Variants, may have a little jazz influence. Although, I like my Five Pieces for Clarinet Alone. I think I could put that in as one of my favorites of my music, and it does have quite a bit of jazz influence. So I still am “bilingual,” I like to speak both languages. If somebody wants me to play the blues, I’m very happy to play the blues. If they want me to play a free improvisation, I’m happy to do that. I love music. And that’s it.

FURTHER READING:

- Bish, Deborah F. “A Biography of William O. Smith: The Composition of a Life.” DMA diss., Arizona State University, 2005.

- Rehfeldt, Philip. “William O. Smith.” The Clarinet 7/3 (Spring 1980), pp. 42-44.

- Suther, Kathryn Hallgrimson. “Two Sides of William O. ‘Bill’ Smith, Part 1.” The Clarinet 24/4 (July/August 1997), pp. 40–44.

- Suther, Kathryn Hallgrimson. “Two Sides of William O. ‘Bill’ Smith, Part 2.” The Clarinet 25/1 (November- December 1997), pp. 42–48.

COMPOSITIONS BY WILLIAM O. SMITH

1. Three Songs for Soprano and Piano (1947)

2. Suite for Clarinet, Flute and Trumpet (1947)

3. Four Songs for Women’s Voices (1947)

4. Four Pieces for String Quartet (1947)

5. Serenade for Flute, Trumpet and Violin (1947)

6. Schizophrenic Scherzo for cl, alto sax, ten sax, tpt, tbn (1947)

7. Sonatina for Flute and Piano (1947)

8. The Hours Rise Up for chorus, fl, cl, tpt, vn (1947)

9. Three Pieces for fl, cl, bn, pno, vn, vla, vcl (1947)

10. Three Songs for sop, alto, cl, bn (1947)

11. Duo for Two Conductors fl, cl, bn, pno, 2 vns, vla, vc (1947)

12. Music for “The Blameless Fool” (1948)

13. Three Pieces for an Experimental Film for fl, cl, bn (1948)

14. Sonata for Clarinet and Piano (1948)

15. Five Songs for Soprano and Piano (1948)

16. Music for “Oedipus Rex” for vn, cl, perc, pno (1948)

17. Anyone for solo soprano, SA chorus, fl, cl, bn, perc, 2 vns, vla, vc (1948)

18. Music for “The Duchess of Malfi” for fl, cl, tpt, pno (1948)

19. Concertino for Trumpet and Jazz Combo for 3 saxes, tpt, tbn, pno, bass, drums (1948)

20. Five Songs for chorus (1949)

21. Clarinet Duets (1949)

22. Five Mother Goose Rhymes for soprano and piano (1949)

23. Music for “Proem” for cl, tpt, vn, and vc (1949)

24. Songs for Soprano and Violin (1949)

25. Quintet for Clarinet and String Quartet (1950)

26. Concerto for Trombone and Chamber Orchestra (1949)

27. Suite from “Four in the Afternoon” for cl, vn and pno (1951)

28. Duo for Violin and Piano (1951)

29. String Quartet (1952)

30. Three Easy Pieces for Viola and Cello (1952)

31. Little Suite for Viola and Cello (1952)

32. Three Poems for Men’s Chorus (1952)

33. Capriccio for Violin and Piano (1952)

34. Suite for Clarinet and Violin (1952)

35. Dance for Two Pianos (1954)

36. Suite for Concert Band (1954)

37. My Father Moved Through Dooms of Love for chorus and orchestra (1955)

38. Divertimento for cl, bn, hn, vn, vc (1955)

39. Five Songs for Male Chorus (1955)

40. Divertimento for Jazz Combo fl, cl, gtr, vib, bass, drums (1956)

41. Concerto for Clarinet and Combo for cl, 3 saxes, hn, tpt, tbn, bass, pno, drums (1957)

42. A Song for Saint Cecilia’s Day (1957)

43. Four Pieces for Clarinet, Violin and Piano (1957)

44. Quartet for Clarinet, Violin, Cello and Piano (1958)

45. Five Pieces for Clarinet Alone (1958)

46. Five Songs for Soprano and Cello (1960)

47. Duo for Clarinet and Tape (1960)

48. Five Pieces for Flute and Clarinet (1961)

49. Duo for Clarinet and Piano (1961)

50. Five Piano Pieces (1961)

51. Five Studies for Two Pianos (1962)

52. Concerto for Jazz Soloist and Orchestra (1962)

53. Explorations for Jazz Combo and Tape (1963)

54. Variants for clarinet alone (1963)

55. Three Latin Lyrics for men’s voices (1963)

56. Fantasy for Flute, Violin and Piano (1963)

57. Five Studies for Clarinet and Violin (1964)

58. Interplay for jazz combo and orchestra (1964)

59. Mosaic for clarinet and piano (1964)

60. Elegy for Eric for jazz combo (1964)

61. Tangents for clarinet and orchestra (1965)

62. Random Suite for clarinet and tape (1965)

63. Studies for Soprano and Clarinet (1965)

64. International Set for jazz combo (1965)

65. Explorations II for Five Instruments (1966)

66. Fancies for clarinet alone (1968)

67. Quadri for jazz combo and orchestra (1968)

68. String Quartet (1969)

69. Ambiente for jazz ensemble (1970)

70. Songs for Myself Alone for soprano and percussion (1970)

71. Quadrodram for cl, tbn, perc and pno (1970)

72. Chamber Muse for cl, perc and dancer (1970)

73. Encounter for cl and tbn (1970)

74. Tu for soprano and percussion (1970)

75. Cartolline for soprano (1970)

76. Stones for soprano and piano (1971)

77. C.B. for solo cello (1972)

78. Roberto for two clarinets 1972)

79. Okisham for soprano solo (1972)

80. Oracle for soprano solo (1972)

81. Straws for fl and bn (1974)

82. Songs for Soprano and Two Clarinets (1974)

83. Jazz Set for Flute and Clarinet (1974)

84. Agate for jazz soloist and jazz orchestra (1974)

85. One for chorus, ob, cl, tpt, tbn vn and vc (1975)

86. Three for soprano, cl, tbn and dancer (1975)

87. Theona for jazz combo and orchestra (1975)

88. Chronos for string quartet (1975)

89. Elegia for cl and strings (1976)

90. Five for brass quintet (1976)

91. Five Fragments for double clarinet (1977)

92. Lines for solo soprano (1977)

93. Epitaph for solo clarinet (1977)

94. Spontaneous Music for tenor voice and chorus (1977)

95. Ilios for chorus, winds and dancers (1977)

96. Tribute to the Bassoon for bassoon (1977)

97. Janus for trombone and jazz ensemble (1977)

98. Mandala I for instruments and voices (1977)

99. Ecco! for cl and orch (1979)

100. Jazz Set for Solo Clarinet (1978)

101. Intermission for soprano, chorus and instruments (1978)

102. Nine Studies for solo clarinet (1978)

103. Webster’s Story for soprano voice, cl and tbn (1978)

104. Soliloquy for cl and two tape recorders (1978)

105. Mu for cl and small orchestra (1978)

106. Fantasy for Solo Flute (1978)

107. Eternal Truths for wind quintet (1979)

108. Session for solo trombone (1979)

109a. Incantation for cl and voices (1979)

109. Twelve for cl and strings (1979)

110. Duo for Clarinet and Cello (1980)

111. Dream Ritual for soprano voice (1980)

112. Solo for electric clarinet (1980)

113. Five for Milan for cl and jazz ensemble (1980)

114. Reflection for cl and voices (1980, rev. 1995)

115. Ritual for two cellos (one player) (1981)

116. Morning Incantation for horn and voices (1981)

117. Mandala III for large flute ensemble (1982)

118. Greetings for five or more clarinets (1982)

119. Thirteen for fl, 2 cls, hn, 2 tbns, vc and pno (1982)

120. Quiet Please for jazz ensemble (1982)

121. Jazz Set for Clarinet and Trombone (1982)

122. Musing for three clarinets (1983)

123. Enchantment for fl and female voices (1983)

124. Pente for cl and string quartet (1983)

125. Jazz Set for Two Clarinets (1983)

126. Trio for Clarinet, Violin and Piano (1984)

127. Eye Music for cl and tbn (1985)

128. Sudana for oboe and voices (1985)

129. Concerto for Clarinet and Small Orchestra (1985)

130. Asana for electric clarinet (1985)

131. Oni for cl, keyboard, perc and electronics (1985)

132. In Memoriam: Roger Sessions for solo cl (1986)

133. Line Up I for flute ensemble (1986)

134. Line Up II for clarinets (1986)

135. Space Music for four piccolos (1986)

136. Line Up III for clarinet ensemble (1986)

137. Jazz Fantasy for two cls (1986)

138. Diversion for wind quintet (1986)

139. Two Blew Too Blue for two cls (1987)

140. Blue Lines for jazz ensemble (1987)

141. Slow Motion for electric clarinet with computer graphics (1987)

142. Music for Five Players for cl and string quartet (1987)

143. Psyche for viola and voices (1987)

144. Illuminated Manuscript for wind quintet with computer graphics (1987)

145. Emerald City Rag for two cls and bass cl

146. Seven Haiku for solo clarinet (1987)

147. Five Inventions for fl and cl (1987)

148. Variations for Three for three cls or basset horns (1988)

149. Around the Blues for two clarinets (1988)

150. Ritual for Double Clarinet (1989)

151. Three Marches for picc, tpt, tbn and perc (1989)

152. Serenade for cl, vn, and vc (1989)

153. Aubade for solo clarinet (1989)

154. In A Minor for instruments and/or voices (1989)

155. Phils Chart for solo clarinet (1989)

156. 64 for demi-clarinet (1989)

157. East Wind for wind ensemble (1990)

158. Alleluia for chorus and/or instruments (1990)

159. Pan for cl and reverberation (1990)

160. Meditations for demi-clarinet (1990)

161. Love Your Neighbor, Gaia and Spring for instruments and voices (1990)

162. Piccolo Concerto for fl, cl, vn, vc and pno (1991)

163. Jazz Set for Violin and Wind Quintet (1991)

164. Misterium Coniunctionis for solo horn (1991)

165. Postcard Piece X for clarinet (1992)

166. Jazz Set for Clarinet and Bass Clarinet (1992)

167. Off the Wall for cl and tbn (1992)

168. Solo for viola (1992)

169. Clarinet Essay for two clarinets (1992)

170. Jazz Fantasy for jazz improvisers and string quartet (1992)

171. Ritual for Clarinet and Viola with perc, tape and projections (1992)

172. Ritual for Clarinet and Percussion (1992)

173. Incantation for solo cl (1992)

174. Ritual for Two Clarinetists with tape and projections (1993)

175. 86910 for cl and digital delay (1993)

176. Epitaphs for double clarinet (1993)

177. Blue Shades for cl and wind ensemble (1993)

178 Soli for fl, cl, vn and vc (1993)

179. Five Pages for two clarinets and computer (1994)

180. Essay for two cls (1995)

181. 66 for double clarinet (1995)

182. Cantus Romanus and Lines for clarinet ensemble (1996)

183. Paris Imp for clarinet and tape (1996)

184. Forest for clarinet (1996)

185. Sayings for saxophone (1996)

186. Tamar for flute and harp (1996)

187. Deluge for clarinet ensemble (1996)

188. Duet for two cls in two tempos (1996)

189. 66 for clarinet solo (1996)

190. Jazz Set for fl, bsn and pno (1997)

191. Sappho for voice, clarinet and harp (1997)

192. Mallets for vibraphone and wind ensemble (1997)

193. Explorations for clarinet and chamber orchestra (1998)

194. Seven Haiku for koto (1998)

195. Peval for E-flat alto clarinet (1998)

196. Duo for clarinet and bass clarinet (1998)

197. Cleopatra’s Garden for clarinet and piano (1998-2000)

198. Transformations for tbn and tape (1999)

199. Blue Ebony for clarinet ensemble (1999)

200. Rites for clarinet and computer-transformed sounds (1999)

201. Quartet for two double cls (1999)

202. 10 x 200 for cl, vn, vc, pno, perc (1999)

203. Flute Concerto (1999)

204. Gestures for clarinet and computer-transformed sounds (2000)

205. Sumi-e for clarinet and computer-transformed sounds (2000)

206. Space for fl, cl, vn, vc and pno (2000)

207. Ottanta for cl and vc (2001)

208. Trias for fl, cl and bn (2001)

209. Crescent Chain for clarinet ensemble (2001)

210. Jazz Set for tbn and perc (2002)

211. Concerto for Jazz Orchestra (2002)

212. Nuria for clarinet alone (2002)

213. Lines for bass clarinet (2002)

214. Five Portraits for chamber ensemble (2003)

215. Blues for Mal for 3 cls and bass cl (2003)

216. Summer Fancy for solo clarinet (2004)

217. Emerald City Imp for fl, cl, bass cl, tbn, vc (2005)

218. Variants for 2 cls (2006)

219. Jazz Set for cl and bass cl (2006)

220. Space in the Heart, a jazzopera for 3 jazz singers and jazz combo (2008)

221. Epigrams for clarinet (2009)

222. Four Duets for 4 demi-clarinets (2009)

223. May I, haiku and interludes for clarinetist (2010)

224. Session, a space song for clarinet ensemble (2012)

225. Jazz Set for flute and violin (2012)

226. Jazz Set for 2 bass cls (2012)

227. Assisi Suite for 2 cls and bass cl (2013)

228. Clarinet Trio for 2 cls and bass cl (2014)

229. Homage to CCCB for clarinet choir (2014)

230. Transformations for clarinet and nonet (2015)

231. Bologna Blues for cl, bass cl and combo (2016)

WILLIAM O. “BILL” SMITH DISCOGRAPHY

As Bill Smith:

Dave Brubeck Octet (1950)

Fantasy OJC – 101

Dave Brubeck, Dick Collins, Bob Collins, Paul Desmond, Dave Kriedt, Jack Weeks, Cal Tjader, Bill Smith

Folk Jazz: Bill Smith Quartet (1956)

Contemporary M359, S7591

Bill Smith, Jim Hall, Monty Budwig, Shelley Manne

Music to Listen to Red Norvo By (1957)

Fantasy OJC-155

Red Norvo, Buddy Collette, Bill Smith, Barney Kessel, Shelley Manne, Monty Budwig

Shelley Manne and His Men, Vol. 6 (1957)

Contemporary M3536

(Concerto for Clarinet and Combo)

Bill Smith, Stu Williamson, Bob Enevoldsen, Vincent De Rosa, Charlie Mariano, Jack Montrose, Bill Holman, Monty Budwig, Shelley Manne

The Riddle (1957)

Columbia CL 1454

Dave Brubeck, Bill Smith, Gene Wright, Joe Morello

Brubeck a la Mode (1960)

Fantasy OJCCD-200-2

Dave Brubeck, Bill Smith, Gene Wright, Joe Morello

Near Myth: Brubeck and Smith (1961)

Fantasy 3319

Dave Brubeck, Bill Smith, Gene Wright, Joe Morello

The American Jazz Ensemble in Rome (1962)

RCA Victor 2557

Bill Smith, John Eaton, Eric Peter, Pierre Favre

The Beat Generation (1963)

RCA Victor PML 10300

(Bill Smith compositions)

Armando Trovajoli Orchestra

New Dimensions (1964)

Epic 16040

Bill Smith, John Eaton, Richard Davis, Paul Motian

Americans in Europe, Vol. 1 (1965)

Impulse 36

Bill Smith, Herb Geller, Jimmy Gourley, Bob Cartet, Joe Harris

Dedicated to Dolphy (Elegy for Eric) (1965)

Cambridge CRS 2820

Bill Smith, Jerome Richardson, Joe Newman, Bob Brookmeyer, Louis Elex, Phil Kraus, Richard Davis, Mel Lewis

Sonorities (1978)

Edi-Pan NPG 901

Bill Smith, Enrico Pieranunzi, Giovanni Tommaso, Pepito Pignatelli

Colours (1978)

Edi-Pan NPG 807

Bill Smith, Enrico Peranunzi, Bruno Tommaso, Roberto Gatto

Journey Without Maps (1979)

Keen 1902100-s

Northwest Jazz Sextet, Bill Smith, Floyd Standifer, Tom Collier, Bill Kotick, Dan Dean, Stan Keen

Live From Midem (1983)

Kool Jazz KM-26001

Dave Brubeck, Bill Smith, Chris Brubeck, Randy Jones

Concord on a Summer Night (1985)

Concord CCD-4198

Dave Brubeck, Bill Smith, Chris Brubeck, Randy Jones

For Iola (1986)

Concord CCD-259

Dave Brubeck, Bill Smith, Chris Brubeck, Randy Jones

Reflections (1987)

Concord CCD-4299

Dave Brubeck, Bill Smith, Chris Brubeck, Randy Jones

Blue Rondo (1987)

Concord CCD-4317

Dave Brubeck, Bill Smith, Chris Brubeck, Randy Jones

Moscow Night (1988)

Concord CCD-4353

Dave Brubeck, Bill Smith, Chris Brubeck, Randy Jones

New Wine (1990)

Musicmasters 5051-2-C

Dave Brubeck, Bill Smith, Chris Brubeck, Randy Jones with the Montreal International Jazz Festival Orchestra

The Christmas Collection (1991 reissue)

Original Jazz Classics: Prestige CR 02

(The Bill Smith Quartet, Greensleeves)

Bill Smith, Jim Hall, Monty Budwig, Shelley Manne

Dave Brubeck Octet (1991 reissue)

Fantasy OJCCD-101-2 (F-3-239)

Dave Brubeck, Paul Desmond, David Van Kriedt, Bill Smith, Dick Collins, Bob Collins, Cal Tjader, Jack Weeks

Once When I Was Very Young (1992)

MusicMasters Jazz 01612-65083-2

Dave Brubeck, Bill Smith, Jack Six, Randy Jones

Pairs! Bill Smith Quartet with Paolo Ravaglia in Rome (1999)

Via Veneto Jazz, RCA Victor 74321 674472

(Bill Smith and Paolo Ravaglia Quintet and Quartet) Bill Smith, Paolo Ravaglia, Andrea Benventano, Pietro Ciancaglini, Gerardo Bartocini, Gianni Di Rienzo

Dave Brubeck – Love Songs (2000)

Columbia CK 66029

Dave Brubeck, Bill Smith (track 8), Eugene Wright, Joe Morello

Dave Brubeck in Montreux (2001)

Westwind 2131

Dave Brubeck, Bill Smith, Chris Brubeck, Randy Jones

Concert for Mirella (2005)

Mox Jazz MMI1/2

Bill Smith, Lanfranco Malaguti, Piero Leveratto, Gianmarco Lanza

Best of Brubeck (2006)

Telarc CCD2 30075-2

Dave Brubeck, Bill Smith, Jack Six, Randy Jones

Night Shift (2006)

Dave Brubeck, Jack Six, Randy Jones, Bobby Militello, Bill Smith, Chris Brubeck

Tram Jazz

BRECCE trambus

Bill Smith, Paolo Ravaglia, Elio Tatti, Giampaolo Ascolese

Bill Smith Quartet / Bill Smith meets Gianmarco Lanza

Helikonia Jazz HKJZ9042

Bill Smith, Lanfranco Malaguti, Gianmarco Lanzi, Paolo Ghetti

As William O. Smith:

Contemporary Composers Series: William O. Smith, Vol. 1

Contemporary C60001, S7015

Andre Previn, Nathan Rubin, the Amati String Quartet, William O. Smith

Contemporary Composers Series: William O. Smith, Vol. 2

Contemporary M6010, S8010

Marni Nixon, Victor Gottlieb, Eudice Shapiro, Ingolf Dahl, William O. Smith

Two Sides of Bill Smith (1974)

Composers Recordings, Inc CRI SD 320

Orchestra U.S.A., Gunther Schuller, conductor, William O. Smith

Winds from the Northwest (1975)

Crystal 351

(Straws, William O. Smith)

Soni Ventorum Wind Quintet

New Music for Clarinet

Mark Records MES 38084

(Solo, William O. Smith)

Gerard Errante, clarinet

New Music for Virtuosos

New World Records 209 (LP)

New World Records: 80541-2 (CD)

(Fancies, William O. Smith)

William O. Smith, clarinet

Clarinet Music

Mark Records MRS 32645

(Variants and Jazz Set, William O. Smith)

William O. Smith, clarinet

The Clarinet of Paul Drushler

Mark Records MRS 32641

(Five Pieces, William O. Smith)

Paul Drushler, clarinet

Unaccompanied Solos for Clarinet, Vol. III

Mark Educational Records, Inc. MRS 32645

(Jazz Set, William O. Smith; Variants, William O. Smith; Episodes, Gunther Schuller)

William O. Smith, clarinet

American Music for Flute

Orion Master Recordings, Inc ORS 84474

(Five Pieces, William O. Smith)

Karl Kraber, flute

John Eaton (Concert Music)

Composers Recordings, Inc CRI SD296

William O. Smith, clarinet

Luigi Nono, Musique Vivante – A Floresta É Jovem E Cheja De Vida

Arcophon AC 6811

William O. Smith, clarinet

Music of William Bergsma

Musical Heritage Society MHS 3533

(Illegible Canons, William Bergsma)

William O. Smith, clarinet

Gail Kubik

Contemporary 8013

(Sonatina, Gail Kubik)

William O. Smith, clarinet

Soni Ventorum

Crystal S257

(Eternal Truths, William O. Smith)

Soni Ventorum Wind Quintet

John Cage – Atlas Elipticalis

Mode 3/6

William O. Smith, clarinet

William O. Smith – Clarinet Music

Pan 3023

William O. Smith, clarinet

Composition N.96 – Anthony Braxton

Leo Records CD LR 169

William O. Smith, clarinet

Soni Ventorum Wind Quintet plays Smith and Schoenberg

Musical Heritage Society 514225K

Jazz Set for Violin and Wind Quintet, William O. Smith

Media Survival Kit

Scarlatti Classica MZQ737707

(Le Tracce di Kronos, I Passi, James Dashow)

William O. Smith, clarinet

Water Colors

Sparkling Beatnik SBR0018

(Seven Haiku for bass koto, William O. Smith)

Eizabeth Falconer, koto

William O. Smith – Solo Music

Ravenna Editions 2001

William O. Smith, clarinet, with Chad Kirby, Stuart Dempster, Jeff Cohan

Bamboo, Silk and Stone

ZA Discs

Randy Raine-Reusch, William O. Smith, Stuart Dempster, Jin Hi Kim, Barry Truax, Jon Gibson

Solo/Tutti – Richard Karpen

Centaur CRC 2716

Garth Knox, Jos Waanenbug, Stuart Dempster, William O. Smith

Crossing The Line

Summit Records DCD1022

(Jazz Fantasy, William O. Smith)

Eddie Daniels and Larry Combs, clarinets

collage//decollage – William O. Smith & Jesse Canterbury

Present Sounds Recordings PS0703

Mavericks – American Modern Ensemble

American Modern Recordings AMR1041 2015

(Sumi-e, William O. Smith)

William O. Smith, clarinet

Unaccompanied Solos for Clarinet – Paul Drushler and William O. Smith

Mark Educational Recordings MRS 32645

Comments are closed.