Originally published in The Clarinet 49/3 (June 2022).

Printed copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

Clarinet Playing During and After Pregnancy

by Rachel Yoder

Every clarinetist who is a parent knows that having a child brings new challenges for our careers. Many of these challenges affect all parents, such as reconciling childcare logistics with concert schedules, and balancing work life with family life. But one set of challenges is faced only by those who give birth to a child: the physical effects of pregnancy and childbirth.

Pregnancy and childbirth can greatly affect the respiratory system and the muscles involved in playing the clarinet, but little research has been done to help wind players and their teachers understand these issues and how to address them. Pregnancy is a life event experienced by many clarinetists – in the U.S., 86% of women have children by age 45 – and understanding its physical challenges could be a step towards addressing gender inequities in the clarinet profession.

Physiological issues involving the abdominal muscles and pelvic floor are not just an issue for women with children. They can be experienced by people of any gender identity who have given birth, women who have never had children, women whose pregnancies result in miscarriage or stillbirth, and people with hernias or undergoing abdominal surgery. It is hoped that this article can serve as a starting point for dialogue on this topic of extreme importance to so many people in our field.

This discussion of clarinet playing during pregnancy and the postpartum period includes information from an online survey of clarinetists who have given birth that was administered in the winter of 2019-2020 and had 57 respondents, all of whom identified as women. Along with these survey results, literature on the physiology of air support and how this physiology may be affected by pregnancy provides helpful perspectives from both medical researchers and instrument-specific scholars. As a starting point for players and teachers, recommendations are offered for clarinet playing in the postpartum period, informed by the survey, medical literature and best practices for supporting new parents in the workplace.

Respiration Anatomy Basics

There are many different descriptions of breathing and breath support in clarinet playing, but Alyssa Powell’s recent survey of literature regarding breathing in both clarinet and voice resources makes several things clear:1,2

1 Inhalation is achieved through expansion of the thoracic cavity (ribcage area) via external intercostal muscles and drawing down of the diaphragm, displacing abdominal viscera downwards and drawing air into the lungs.

2 Exhalation occurs as the diaphragm and external intercostals relax, pressure increases inside the lungs and air moves out of the lungs.

3 A controlled exhalation for clarinet playing is most often achieved through “muscular antagonism,” or breath support, achieved by activating opposing muscles of inspiration and expiration to regulate the airstream.

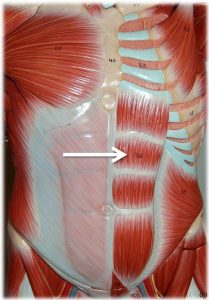

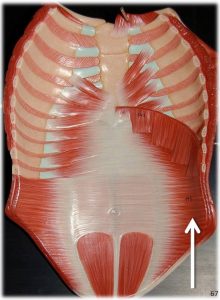

Clarinetists do not all describe breathing in the same way, but most advocate either some form of abdominal breathing, or breathing that incorporates elements of abdominal breathing and thoracic breathing.3 The exact muscles used in air support may include the intercostals, obliques, rectus abdominis, transverse abdominis and others (see Figure 1). As we shall see, pregnancy has many effects on the body that may impact these musculoskeletal structures and functions.

Physical Changes During Pregnancy

The body’s changes during pregnancy are extreme and vary greatly for each individual. Common physical effects of pregnancy include fatigue (experienced in about 90% of pregnancies), nausea and/or vomiting (80%), lower back pain or pelvic girdle pain (50%), and urinary incontinence.4 The volume of blood circulating in the body increases by about 50%,5 and hormones cause ligaments and muscles to loosen and relax.

As the baby grows and the uterus expands, the abdominal area adjusts. Weight gain of 25-35 pounds is common, and 65% of this is in the abdominal area.6 The abdominal muscles thin and lengthen, and the action of these muscles is reduced.7

Pregnancy and the Respiratory System

Figure 1: Rectus abdominis and transverse abdominis muscles

Photos, text, and labels by Rob Swatski, Assistant Professor of Biology, Harrisburg Area Community College – York Campus, York, PA. Email: [email protected]

The respiratory system has amazing ways of adapting to these changes. Over the course of three trimesters, the ribcage expands upwards and widens, the abdominal muscles lengthen, and the diaphragm shifts upward by as much as 4 cm, while incredibly, the lung volume remains unchanged.8 The body also adapts by increasing the volume of air inhaled/exhaled per minute at rest by up to 50% through mechanisms such as reducing the airway resistance.9,10 But because of lowered ability to access lung reserves to increase this volume during stress or heavy exercise, the body’s capacity for strenuous exercise is impaired, and less oxygen is available for it.11

Research has shown that classically trained singers use most of their lung capacity when singing.12 It may be presumed that professional clarinetists also typically use the full reserves of their lungs while playing, and that the inability to access these reserves during pregnancy could have noticeable impacts on performance.

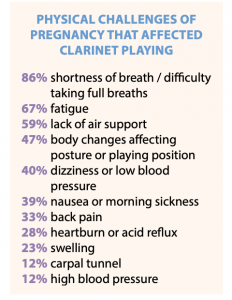

Survey Results: Clarinet Playing During Pregnancy

Figure 2: Responses to survey question, “What physical challenges did you face during your pregnancy that affected your clarinet playing?”

Data from the 2019-2020 survey on clarinet playing during and after pregnancy provide details on how these physical changes affect clarinetists. Figure 2 shows that most clarinet players found shortness of breath and lack of air support to be an issue, with fatigue also impacting their clarinet playing. One respondent noted, “As baby grew in size, it was increasingly challenging to take deep enough breaths and to sustain them adequately. It was also necessary to modify my playing position due to [my] increasingly large belly.” Others stated: “I could barely take a deep enough breath to sustain any length of phrasing.” “Couldn’t get a full breath towards end of pregnancy. Thank goodness I didn’t have any performances in my third trimester!” “I played professionally until I wasn’t able to support my sound without feeling very uncomfortable. This was about midway through my eighth month.”

Dizziness or low blood pressure, experienced by 40% of respondents, may make it difficult to stand while playing, while swelling can cause difficulty with sitting. One woman said that “the swelling made it really hard to sit for long periods of time,” while another had the opposite problem:

I had to sit to play during the majority of my pregnancy. When I would stand and play I would become really light-headed and feel like I might pass out. This started very early in the pregnancy – around 2-3 months. I kept playing until month 8, but always had to sit.

Nausea/morning sickness impacted the clarinet playing of nearly 2 in 5 survey respondents, and while carpal tunnel was less common, it is obviously a serious concern for clarinetists.

The growing baby can also affect posture and playing position, as reported by 47% of clarinetists – especially with bass clarinet. Nine of the 57 clarinetists surveyed mentioned that the bass clarinet brought specific challenges with air support and angle of the instrument. One stated, “In my eighth month with my first, I was asked to play bass clarinet for an orchestra; I wasn’t able to reach around my belly to play.” Another said, “Bass clarinet was nearly impossible to play during my pregnancy. The increased air and support caused abdominal pain.” Additionally, two people mentioned difficulty carrying the bass clarinet case.

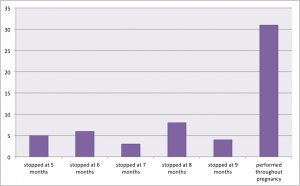

Figure 3: Responses to the survey question, “In what month of your most recent pregnancy did you cease performing

Most women (80.7%) reported that at least one of these symptoms worsened as pregnancy progressed. At the fifth month of pregnancy, 38% of survey respondents felt that the pregnancy affected their clarinet playing. By the seventh month, it was 74%, and by the ninth month, 86% reported that their clarinet playing was affected.

With all of these challenges, clarinetists who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant may wonder, “Will I have to stop playing the clarinet, and if so, when?” It is impossible to predict what will happen in each individual case, but the survey provides some insights (see Fig. 3). More than half (54.4%) of women continued to perform and practice throughout their entire pregnancy. In month 5 some women began stopping performance and practice activity, and this number increased until the ninth month, by which 45.6% of women had stopped practicing and performing.

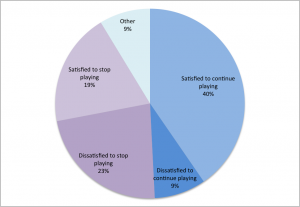

Figure 4: Responses to the survey question, “How did you feel about the choice to continue or discontinue playing during your pregnancy?”

When asked about the decision to stop playing, about half of those who had to stop were dissatisfied to have to stop playing (see Fig. 4). The other half were content to stop playing when they did. On the other hand, some clarinetists continued playing longer than they would have liked, presumably due to career or school demands. One woman wrote,

I was in a terminal degree program. I gave a full-length recital at 37 weeks pregnant and gave concerts up until the week I gave birth. My playing had become so manufactured by that point that I was in terrible fundamental clarinet shape after having the baby. I had developed so many bad habits during the pregnancy, in order to cope with the responsibilities I had to fulfill. … [it] took a tremendous emotional and mental toll.

The Postpartum Period

After childbirth, a new set of challenges presents itself as the body recovers and parents take on the tremendous responsibility of caring for a newborn. Fatigue is common, with newborns requiring breastfeeding, pumping or formula feeding 8 to 12 times per day. Postpartum depression and anxiety are a common concern; up to 50% of women in the general population may have depressive symptoms in the 12 months after childbirth, with 20% experiencing postpartum depression.13

Physical challenges during this period can include pelvic floor issues and diastasis recti (separation of the rectus abdominis muscles). A 2016 study found that 60% of women experienced diastasis recti at 6 weeks postpartum, and about 33% still had this separation one year postpartum.14 Pelvic floor weakness, incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse are also common. Pelvic floor muscle strength is significantly reduced at 6-12 weeks postpartum, especially after vaginal birth but with significant weakening also occurring after caesarean section.15 C-section deliveries also may require 4 to 6 weeks of recovery until exercise is advised.16

While the respiratory system recovers within 6-12 weeks postpartum,17 it usually takes at least 8 weeks after birth for the abdominal muscles to be able to stabilize the pelvis against resistance.18 The rectus abdominis likely recovers first, followed by the transverse abdominis and obliques.19 Internal and external obliques may be overused to compensate for the weaker transverse abdominis.20

Survey Results: The Postpartum Period

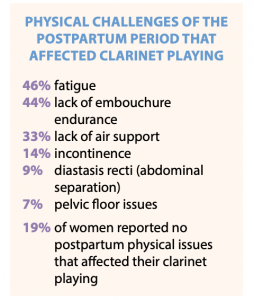

Figure 5: Responses to the survey question, “What physical challenges did you face in the year after giving birth that may have affected your clarinet playing (or been worsened by clarinet playing)?”

In the survey of clarinetists, the top two physical challenges of the postpartum period that affected playing were fatigue and lack of embouchure endurance (see Figure 5). About a third of clarinetists mentioned a lack of air support being an issue.

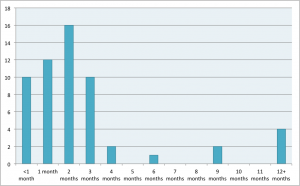

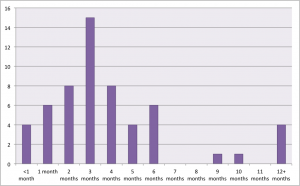

Physical recovery time varies depending on the individual, but from the survey responses we can begin to see some general trends on when clarinetists were able to get back to playing after childbirth. Most women had returned to practicing by 3 months postpartum, and performing by 6 months postpartum (see Figures 6 and 7).

However, nearly a third of women had resumed performing by 2 months postpartum – presumably before the respiratory system and abdominal muscles had time to recover from pregnancy. Professional or financial obligations were a factor for some women in returning before they were physically ready. One noted, “I started playing again too soon (in my opinion) after having a C-section. A lot of extra pressure on my abdomen, but I felt if I didn’t do the gig I was at risk of losing it.”

Figure 6: Responses to the survey question, “Indicate how many

months after giving birth you returned to regular clarinet practice.”

Another wrote:

I had to return to work and playing before healing properly, and while dealing with infections. As a first-time mom, I was expecting challenges during later pregnancy, but the postpartum pain has been much worse than discomfort I experienced playing while pregnant… I often was told the pelvic pain was normal (even though it continued to be consistent well into the fourth month postpartum). That pain still returns (7.5 months postpartum) on certain days or if I play while standing for too long.

On the other hand, six respondents took 9 months or more before returning to practice and performance. It is unclear whether this was a desired outcome or not. Though perhaps not a physical concern, mental health may need attention in this period, with more than a quarter of clarinetists in the survey indicating they had increased anxiety or depression during or after pregnancy that affected their playing. One woman reported:

Figure 7: Responses to the survey question, “Indicate how many months after giving birth you returned to performing.”

My PPA/PPD [postpartum anxiety/postpartum depression] delayed choosing to play. It was the very last thing on my mind for a really long time and I honestly did not see me ever playing again. Once the postpartum disorders lifted a bit, I remembered that I had committed to playing at an event and picked up my instrument. It was so soothing to be good at something without much effort and greatly aided in coping with PPA/PPD.

Physical recovery in the postpartum period21

Research from the medical field on postpartum recovery, especially recommendations for athletes, may give insight for clarinetists and their teachers. Low-impact activities such as walking and aerobics can resume soon after birth, but movement that increases intra-abdominal pressure (such as heavy lifting or squats) should be approached with a “pelvic floor muscle first” focus.22 This involves contracting the pelvic floor (as in a Kegel exercise) before and during the exercise.

Reintegrating the pelvic floor with core abdominal muscles is also key. During pelvic floor contractions, the transverse abdominis and internal obliques co-contract.23,24 One researcher explains a basic approach:

The TVA [transverse abdominis], because it is the deepest of the abdominal muscles and because of the direction of the muscle fibers, is the key to overall spinal stability and abdominal strength. It should be strengthened initially, before more complicated exercises are attempted. This is usually done by lying flat on the back and pulling in the abs, pressing the lower back into the floor while continuing to breathe. Abdominal exercises are most effective when done several times per day, rather than one time per day or once per week.25

It appears that many of the same muscles we use for air support are linked to the pelvic floor and overall core stability. To allow time for the pelvic floor to recover, it may be advisable to avoid strenuous exercise and activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure (such as heavy lifting) in the first few months postpartum, but more research in this area is needed.26 Given that singing and wind playing increase intra-abdominal pressure,27,28,29 and activities increasing intra-abdominal pressure may exacerbate conditions such as pelvic organ prolapse, diastasis recti or hernia, there is a great need for more research to determine medically-informed guidelines for returning to wind instrument playing safely after childbirth.

The clarinetists surveyed indicated that personal fitness activities aided in their postpartum physical recovery, including cardio exercises such as walking, running or biking (75%), Kegel exercises (53%) and yoga (26%). Only 17.5% of clarinetists surveyed did physical therapy, which is routine postpartum care in some countries but less common in others. Of those who did, half said the physical therapy was helpful to their clarinet playing, and all said it was helpful to their postpartum recovery.

Other options may be useful. Occupational therapy could address issues in clarinet playing after initial physical recovery. Medication may be indicated for specific conditions. Abdominal hypopressive training appears to be a safe and effective way to strengthen the abdominal muscles, especially the transverse abdominis, in the postpartum period.30

Comments from survey responses indicate how physical activity helped clarinet playing: “Once my core recovered and I was able to do light cardio, playing became easier.” And: “Getting back in shape physically definitely had a positive impact in my playing. Breathing and air support felt much better!”

Specific exercise recommendations depend on the individual and are outside the scope of this paper, but it is clear that for a healthy return to playing, physical fitness should be prioritized. Making time for self-care can be very difficult when caring for a newborn, but new parents should plan to devote some time and effort to postpartum physical recovery.

Recommendations for clarinetists

For clarinetists who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant, the following recommendations may be helpful:

- Have backup plans. It is impossible to control or predict what will happen and how you will feel during and after pregnancy.

- Consider concert logistics and equipment adjustments. Bass clarinet could be more difficult to play and carry in the third trimester; have backup plans for repertoire that includes bass or contra. You may find it difficult to stand and play, or it could be uncomfortable to sit for long periods. Speak up for what you need and consider keeping a chair near you when performing standing, in case you feel lightheaded. When returning to play after pregnancy, use softer reeds to reduce pressure as your air support and embouchure recover.

- Safely strengthen your core. After pregnancy, gradually strengthen the core with a focus on “pelvic floor first” and then the abdominals, especially the transverse abdominis. The yoga concepts of mula bandha and uddiyana bandha may be relevant for those who practice in that tradition. Cardio exercise is important to overall physical recovery and wellbeing, and postpartum physical therapy is highly recommended.

- Aim for quality of practice, not quantity. You will likely not have the amount of practice time you did before having a baby, but you can learn to be efficient and productive with the time you do have.

- Prioritize your physical and mental health. It is impossible to do your best as a parent and musician if you ignore the needs of your mind and body during this intense time of life.

Recommendations for teachers, administrators and ensemble directors

- Be aware of the physical challenges of pregnancy and the postpartum period.

- Be prepared to make appropriate accommodations in tenure timeline, performance reviews, scheduling, degree plan, repertoire, logistics (e.g., playing seated rather than standing), and breastfeeding or pumping (both space and time allowed).

- Respect each individual’s requests and decisions regarding necessary accommodations, playing during pregnancy, and returning to playing after childbirth.

- Be familiar with family leave provisions at the national and state levels.

- Be an advocate for family-friendly policies at the national, state and local levels and within your own institution or organization, including paid family leave, breastfeeding accommodations, and ensuring that no one is discriminated against due to pregnancy or parenthood, including employment opportunities and

career advancement.

Conclusion

For clarinetists who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant, the potential impacts to the physiology of playing must be considered by the player and their teacher and/or employer. Though the challenges may be major or minor, they are prevalent. Of the 57 survey respondents, only three reported having no physical challenges during pregnancy that affected their clarinet playing, and only 10 reported no such challenges during the year after childbirth.

Regarding the effects of pregnancy on wind players, much more research is needed. Our field would greatly benefit from clinical studies of pregnant and postpartum wind players, as well as more investigation into the effects of pregnancy on the mental and emotional health of musicians. The survey of clarinetists did not gather location information, but it is likely that clarinetists in English-speaking areas were overrepresented, and the survey may not reflect the experiences of clarinetists in other parts of the world. The pedagogy of wind playing also still lacks knowledge specific to the female body, not just in pregnancy but in questions such as how the differing pelvis shapes of men and women may affect air support.

The Brass Bodies Study, a research effort focused on female brass musicians, noted many of the same difficulties as in the clarinet survey, along with some positive outcomes:

A tubist who’d given birth to twins reported that her diaphragmatic strength ebbed to nearly nothing by full-term. A hornist had to figure out new posture and breathing regimens to accommodate pelvic prolapse, a postpartum condition that occurs frequently from multiple births. Pregnant brass players often reported struggling with bladder control during standard union rehearsal schedules and having to negotiate the carriage and weight of their instrument. … [T]hese participants received virtually no support from others in adapting to the changes in their bodies. They figured out for themselves how to manage with less air, less energy, less coordination, less time. Out of these seeming restrictions, however, came new insights into more efficient breathing, more creative use of limited practice time, and a heightened sense of pragmatism.31

While many clarinetists today have successfully risen to meet the challenges of pregnancy and parenthood, less visible are those who may have dropped out of the field or compromised their ambitions due to ongoing physical difficulties, lack of child care, an unsupportive work environment or any combination of other factors. Understanding the possible impacts of pregnancy and childbirth on clarinet playing is a first step in the ongoing discussion about equity and support for women and families in our profession.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the following women who read early drafts of the survey, proofread my article and/or contributed guidance about my research: Kensley Behel, Deanna Brizgys, Emily Kerski, Kellie Lignitz-Hahn, Tori Okwabi, Alyssa Powell, Meghan Taylor, Valerie Tung, and my amazing physical therapist, Vanda Szekely.

Endnotes

1 Alyssa Powell, “Clarinet Breathing: Anatomy, Physiology, and Pedagogy,” Virtual ClarinetFest® presentation, July 24, 2021.

2 Alyssa Powell, “Making the Clarinet Sing: Enhancing Clarinet Tone, Breathing, and Phrase Nuance through Voice Pedagogy,” D.M.A. document, The Ohio State University, 2020.

3 Powell, “Clarinet Breathing.”

4 Kari Bø, et al., “Exercise and Pregnancy in Recreational and Elite Athletes: 2016 Evidence Summary from the IOC Expert Group Meeting, Lausanne. Part 1 – Exercise in Women Planning Pregnancy and Those Who are Pregnant,” British journal of sports medicine 50.10 (2016): 571, ProQuest.

5 Kari Bø, “Exercise and Pregnancy, Part 1.”

6 A. LoMauro, A. Aliverti, P. Frykholm, et al., “Adaptation of lung, chest wall, and respiratory muscles during pregnancy: preparing for birth,” Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md.: 1985), 2019 Dec; 127(6):1640-1650.

7 W.L. Gilleard, and J.M. Brown, “Structure and function of the abdominal muscles in primigravid subjects during pregnancy and the immediate postbirth period,” Physical therapy vol. 76,7 (1996): 750-62.

8 A. LoMauro et al., “Adaptation.”

9 ACOG Committee Opinion No. 804, “Physical Activity and Exercise During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period,” Obstetrics and Gynecology Vol. 135, No. 4, April 2020.

10 Kari Bø, “Exercise and Pregnancy, Part 1.”

11 ACOG Committee, “Physical Activity.”

12 S. Salomoni, W. van den Hoorn, and P. Hodges, “Breathing and Singing: Objective Characterization of Breathing Patterns in Classical Singers,” PloS one, 11(5), 2016, e0155084.

13 Kari Bø, et al., “Exercise and Pregnancy in Recreational and Elite Athletes: 2016/17 Evidence Summary from the IOC Expert Group Meeting, Lausanne. Part 3 – Exercise in the Postpartum Period,” British journal of sports medicine 51.21 (2017): 1516.

14 Jorun Bakken Sperstad, Merete Kolberg Tennfjord, Gunvor Hilde, Marie Ellström-Engh, Kari Bø, “Diastasis recti abdominis during pregnancy and 12 months after childbirth: prevalence, risk factors and report of lumbopelvic pain,” British journal of sports medicine 50 (2016), 1092-1096.

15 T. Sigurdardottir, T. Steingrimsdottir, A. Arnason, et al., “Pelvic floor muscle function before and after first childbirth,” Int Urogynecol J 22, 1497–1503 (2011).

16 Kari Bø, “Exercise and Pregnancy, Part 3.”

17 Kari Bø, “Exercise and Pregnancy, Part 3.”

18 W.L. Gilleard and J.M. Brown, “Structure and function.”

19 “Recovery of Abdominal Muscle Thickness and Contractile Function in Women After Childbirth,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 4 (2021): 2130.

20 Ibid.

21 This paper provides general recommendations only and should not be considered as medical advice. Please consult a doctor or specialist before undertaking any exercise or rehabilitation regimen.

22 Kari Bø, et al., “Exercise and Pregnancy in Recreational and Elite Athletes: 2016/2017 Evidence Summary from the IOC Expert Group Meeting, Lausanne. Part 5. Recommendations for Health Professionals and Active Women,” British journal of sports medicine 52.17 (2018): 1080.

23 Kari Bø and Margaret Sherburn, “Evaluation of Female Pelvic-Floor Muscle Function and Strength,” Physical Therapy 85, no. 3 (03, 2005): 269-82.

24 P. Neumann, and V. Gill, “Pelvic floor and abdominal muscle interaction: EMG activity and intra-abdominal pressure,” International urogynecology journal and pelvic floor dysfunction vol. 13,2 (2002): 125-32.

25 Shel Swanson, “Abdominal Muscles in Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period,” International Journal of Childbirth Education 16, no. 4 (12, 2001): 12.

26 Kari Bø, “Exercise and Pregnancy, Part 3.”

27 S. Salomoni, W. van den Hoorn and P Hodges, “Breathing and Singing.”

28 Kae Okoshi, Taro Minami, Masahiro Kikuchi and Yasuko Tomizawa, “Musical Instrument-Associated Health Issues and Their Management,” The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine (2017), 243; 49-56.

29 Arno Vosk, “Bagpiper’s hernia,” Medical Problems of Performing Artists, Vol. 24, No. 2, 2009, p. 97+.

30 Maria del Mar Moreno-Muñoz, et al., “The Effects of Abdominal Hypopressive Training on Postural Control and Deep Trunk Muscle Activation: A Randomized Controlled Trial,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, No. 5 (2021): 2741.

31 Sarah Schmalenberger, “Brass Bodies Study Offers New Understanding on the Distinctive Physicality of Female Brass Musicians,” International Musician 01 2020: 18.

About the Writer

Seattle-based clarinetist Rachel Yoder performs in a variety of solo, chamber and large ensemble roles, including with the Seattle Modern Orchestra and Odd Partials clarinet/electronics duo. She is adjunct professor of music theory, chamber music and clarinet at the DigiPen Institute of Technology, and editor of The Clarinet.

Comments are closed.