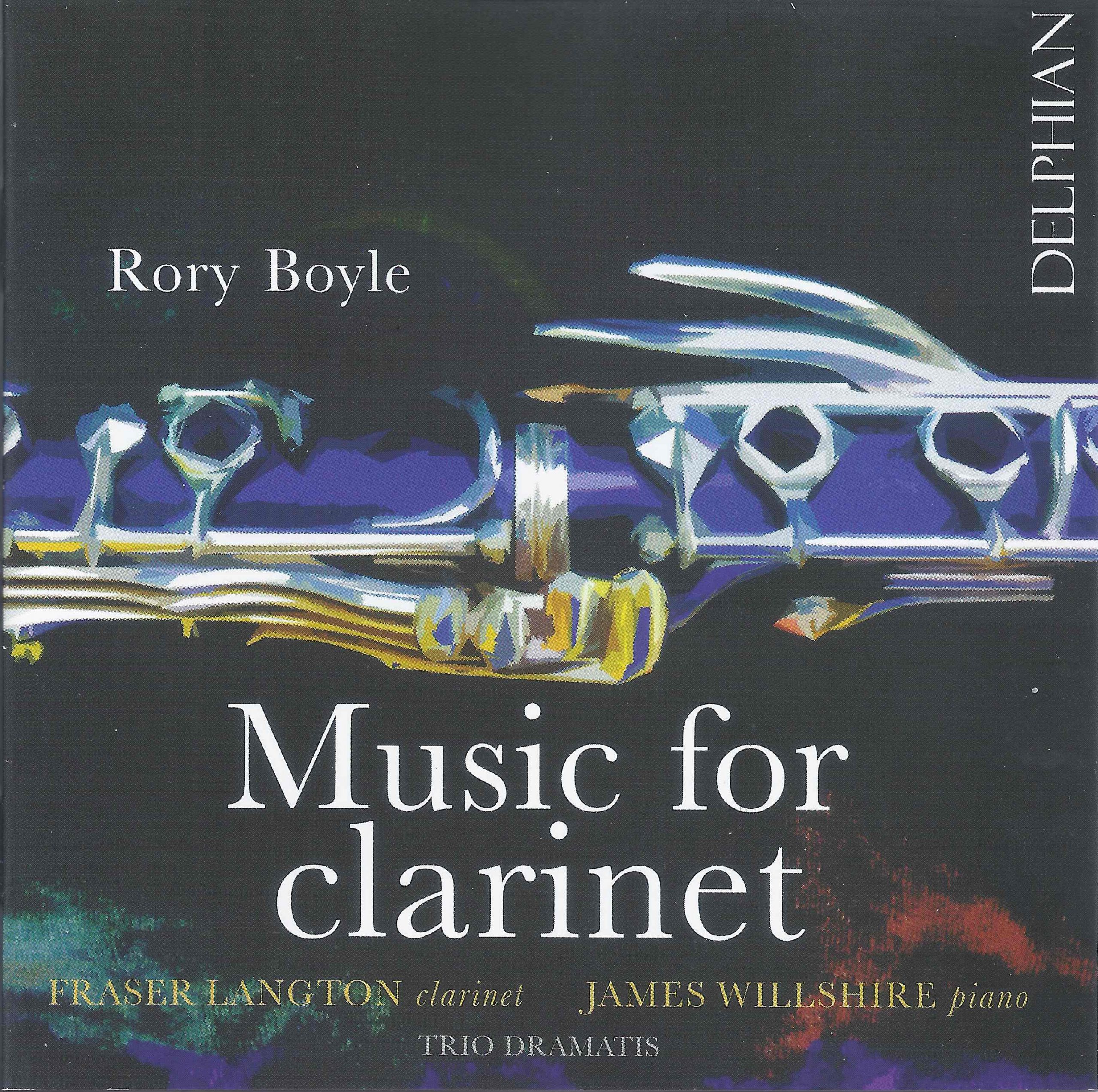

Rory Boyle: Music for Clarinet. Fraser Langton, clarinet; James Willshire, piano. R. Boyle: Sonatina for Clarinet and Piano, Burble, Four Bagatelles, Tatty’s Dance, Dramatis Personae, and Di Tre Re e Io. Delphian Records DCD34172. Total time 60:08. iTunes and Amazon

This new recording features music written by the award-winning Scottish composer Rory Boyle (b. 1951). Composed over a 36-year span, from the 1979 Sonatina for Clarinet and Piano to Di Tre Re e Io, a trio commissioned in 2015, it represents a significant body of work. All of the music was new to this reviewer, and there is much to recommend: it is inventive, colorful, rhythmically incisive, emotionally wide-ranging, economical and with a certain transparency of sound that is very attractive. Clarinetists everywhere should study this repertoire and consider it for inclusion in solo and chamber music recitals. Boyle studied clarinet in his youth, and his knowledge and affinity for the instrument are everywhere apparent.

This new recording features music written by the award-winning Scottish composer Rory Boyle (b. 1951). Composed over a 36-year span, from the 1979 Sonatina for Clarinet and Piano to Di Tre Re e Io, a trio commissioned in 2015, it represents a significant body of work. All of the music was new to this reviewer, and there is much to recommend: it is inventive, colorful, rhythmically incisive, emotionally wide-ranging, economical and with a certain transparency of sound that is very attractive. Clarinetists everywhere should study this repertoire and consider it for inclusion in solo and chamber music recitals. Boyle studied clarinet in his youth, and his knowledge and affinity for the instrument are everywhere apparent.

The disc begins with the youthful three-movement Sonatina for Clarinet and Piano, written in 1979 as a present to Boyle’s composition teacher, Lennox Berkeley. Essentially lighthearted, it is rhythmic and tuneful, with not one superfluous note.

Burble for solo clarinet (2012) was commissioned by and written for Fraser Langton, the clarinetist on this recording. Boyle notes: “Two possible definitions of the word ‘burble’ are a gurgling or bubbling sound and a rapid excited flow of speech, both of which are portrayed in the music in various ways.” This technically challenging piece features huge leaps, trills, glissandos, alternate fingerings, and a wide dynamic range. It would make a stunning solo work on any recital, but one type of player comes to mind: the ambitious post-graduate clarinetist who enjoys giving the local premiere of a very interesting but relatively unknown work.

Four Bagatelles, dating from 1979, was revised in 2014 to create a collection of showpieces for clarinet and piano. At turns witty, sardonic, and highly dramatic, its interior quality reminds this listener occasionally of Alban Berg’s Four Pieces from 1913.

Tatty’s Dance, a short piece written in 2010 for solo piano in honor of the composer’s wife’s birthday, was subsequently revised into a duet for clarinet and piano. This ebullient, infectious tune would make an effective recital encore.

Dramatis Personae was written in 2012 and dedicated to Fraser Langton and James Willshire. Technically and rhythmically demanding, it is in three widely contrasting movements: “Rogue,” “Shadow” and “Fool.” This exciting piece has a decidedly theatrical air, and Boyle exploits the extreme upper register of the clarinet to excellent effect.

The trio Di Tre Re e Io (2015) was inspired by the music of Arthur Honegger, specifically, his Symphony No. 5, which Boyle discovered as a teenager, and whose haunting sound world has fascinated him ever since. Boyle describes this trio as a “personal homage” to Honegger. Its complex, dream-like atmosphere is magnetic.

Performances are uniformly excellent. Langton, who is principal E-flat and assistant principal clarinet with the BBC Philharmonic, displays admirable control throughout a huge dynamic and pitch range. His technique is impressive, and his phrasing is always emotionally compelling. Pianist James Willshire is an ideal collaborator: alert, rhythmically incisive, and technically adroit. Violist Rosalind Ventris joins her colleagues in Di Tre Re e Io, and her contributions are first-rate. Recorded balances are generally excellent, although I could have wished for a little more piano at a few moments.

This recording is highly recommended, and Langton and his colleagues are to be congratulated for bringing Rory Boyle’s wonderful music to a wider audience.

Larry Guy

Mind Music. Elizabeth Jordan, clarinets and basset horn; Lynsey Marsh, clarinet; Northern Chamber Orchestra conducted by Stephen Barlow. F. Mendelssohn: Concert Piece No. 1 in F Major, Op. 113, for clarinet, basset horn and orchestra; R. Strauss: Sonatina in F Major for wind instruments, “From an Invalid’s Workshop,” AV135; J. Adams: Gnarly Buttons; K. Malone: The Last Memory. Divine Art Records DDA 25138. Total time 88:23. Presto Classical, ArkivMusic and Amazon

The English clarinetists Elizabeth Jordan and Lynsey Marsh had an unusual motivation for producing this two-disc set: each woman experienced the death of a parent in 2014 due to complications related to Parkinson’s disease. Beginning with a concert to raise money for a charitable organization called Parkinson’s U.K., the idea expanded to include a studio recording. Most of the works in the set have some connection, through their composers, to neurodegenerative diseases, and all proceeds from the sale of the recording will be donated to Parkinson’s charities.

The English clarinetists Elizabeth Jordan and Lynsey Marsh had an unusual motivation for producing this two-disc set: each woman experienced the death of a parent in 2014 due to complications related to Parkinson’s disease. Beginning with a concert to raise money for a charitable organization called Parkinson’s U.K., the idea expanded to include a studio recording. Most of the works in the set have some connection, through their composers, to neurodegenerative diseases, and all proceeds from the sale of the recording will be donated to Parkinson’s charities.

Some readers of The Clarinet may not be familiar with the featured performers on this recording. Both have been associated with orchestras in and around Manchester. Elizabeth Jordan is principal clarinetist with the Northern Chamber Orchestra and has also played as guest principal with other important English orchestras. Lynsey Marsh served as principal clarinet with the Hallé Orchestra between 2001 and 2015, and has numerous recordings to her credit.

The liner notes for this recording explain why these particular composers have been chosen for inclusion. It is well-known that Mendelssohn died tragically young, but apparently the “Nervenschlag” that killed him is now believed to have been a type of brain hemorrhage that is sometimes associated with Parkinson’s. One might wonder if the world needs another recording of either of the Mendelssohn Concert Pieces, but certainly the performance given here of the F major (with Marsh on clarinet and Jordan on basset horn) is a fine one. Marsh conducts, as well as performing.

Of more interest, at least to this reviewer, is the other repertoire in the set. The Strauss Sonatina “From an Invalid’s Workshop,” has received a number of recordings over the years but is nevertheless relatively little played, which is a shame – it’s a wonderful work. Strauss was ill when he wrote the piece (hence the subtitle), but his malady had nothing to do with anything neurological, so the connection with the theme of the disc is absent in this case. No matter. This performance by the wind personnel of the Northern Chamber Orchestra (with Jordan on C clarinet and Marsh on B-flat/A, along with three other colleagues in the clarinet section) is beautifully shaped by conductor Stephen Barlow. The ensemble plays with impeccable intonation and great expression.

John Adams’s Gnarly Buttons, premiered in 1996, has received relatively few recordings since that time, and Elizabeth Jordan’s is a welcome addition to the discography. Here the connection with the theme of the disc is apparent; Adams’s father, a clarinetist, died of Alzheimer’s disease, and the work was at least partly a reaction by the composer to that event. Jordan’s performance is excellent. She plays with a consistently warm tone, and has complete command of the stylistic idiom and technical difficulties of the work.

The final piece on the recording, The Last Memory by Kevin Malone, is for solo clarinet and digital delay. Like Adams, Malone witnessed his father’s decline due to Alzheimer’s, writing this work in response. Both the piece and Lynsey Marsh’s performance of it are very effective. All in all this CD is worth purchasing not only for the repertoire and performances, but also because it raises awareness of (and money for) an important cause.

Jane Ellsworth

Emil Jonason Plays Lindberg and Golijov. Emil Jonason, clarinet and bass clarinet; Norrköping Symphony Orchestra conducted by Christian Lindberg; Vamlingbo Quartet: Andrej Power and Erik Arvinder, violin; Riikka Repo, viola; Erik Wahlgren, cello. C. Lindberg: The Erratic Dreams of Mr. Grönstedt; O. Golijov: The Dreams and Prayers of Isaac the Blind. Bis Records BIS-2188. Total time 59:57. Naxos, iTunes and Amazon

This release by clarinetist Emil Jonason includes two works that comment on aspects of human awareness that go beyond normal consciousness. The relatively new piece, Christian Lindberg’s The Erratic Dreams of Mr. Grönstedt, is a somewhat programmatic description of various nocturnal visions, while Osvaldo Golijov’s The Dreams and Prayers of Isaac the Blind attempts to invoke different aspects of the transformational power of prayer or meditation through music.

This release by clarinetist Emil Jonason includes two works that comment on aspects of human awareness that go beyond normal consciousness. The relatively new piece, Christian Lindberg’s The Erratic Dreams of Mr. Grönstedt, is a somewhat programmatic description of various nocturnal visions, while Osvaldo Golijov’s The Dreams and Prayers of Isaac the Blind attempts to invoke different aspects of the transformational power of prayer or meditation through music.

Emil Jonason is an absolutely fantastic clarinetist, possessing the prodigious technique required to perform these highly demanding works, and on this recording it seems as if he plays with a reckless abandon that nevertheless is uncannily precise. He has been selected as a “Rising Star” by the European Concert Hall Organisation (ECHO) and Lindberg calls him “one of Sweden’s most promising musicians” in the liner notes. Jonason currently tours as a soloist and teaches at the Stockholm Royal College of Music and at Mälardalen University, Västerås.

The Erratic Dreams of Mr. Grönstedt was written with a great deal of collaboration between Jonason and Lindberg and it was fully intended to showcase Jonason’s abilities. It consists of five movements performed without pause that are loosely programmatic but without a connecting plot. “The Mirror of Saturn” is a fantastic opening to the concerto, with the soloist and basses appearing out of nowhere. The clarinetist enters on a chalumeau E from niente, which soon races off into scattering riffs of color. This explodes into the second movement, “Mr. Grönstedt Dresses for the Spring Ball,” in a rollicking and jaunty tune that contrasts rhythmic underpinnings in the strings with clarinet coloratura passages. As the concerto progresses through “Lisa and the Magic Cape,” “Grönstedt Looks for Treasures on a Rubbish Heap” and “The Dream of Venus,” the music becomes increasingly unhinged. The clarinet, along with the other winds and percussion in the orchestra, weave crazy, neurotic passages through the illogical and fantastical nature of dreams, while the strings attempt to provide some sort of foundation in both a literal and metaphorical sense. This culminates in some incredibly rapid clarinet lines punctuated with multiphonics while humming, flutter tonguing, and some spoken words. The latter part of “The Dream of Venus” is hauntingly calm and serene before a boisterous coda that recalls Mr. Grönstedt’s earlier adventures.

The Dreams and Prayers of Isaac the Blind will be familiar to many listeners. It is similar to the Lindberg in that the music attempts to depict other levels of human consciousness, but different in that the essence of the music is more sacred and prayerful. Golijov writes in the program notes:

The movements of this work sound to me as if written in three of the different languages spoken by the Jewish people throughout our history. This somehow reflects the composition’s epic nature. I hear the prelude and the first movement, the most ancient, in Aramaic; the second movement is in Yiddish, the rich and fragile language of a long exile; the third movement and postlude are in sacred Hebrew…But blindness is as important in this work as dreaming and praying. I had always the intuition that, in order to achieve the highest possible intensity in a performance, musicians should play, metaphorically speaking, “blind.”

It is interesting to note that Jonason has an extensive background in klezmer music, having toured with several klezmer bands in Europe. This is important as Golijov deems essential a background in klezmer in order for The Dreams and Prayers of Isaac the Blind to make artistic sense.

The selection of these two pieces fits Jonason perfectly: the Lindberg was written specifically for him, and he possesses the necessary klezmer background and chutzpah to perform the Golijov in an extremely compelling way. His playing is top-rate with seamless connections across all registers and an altissimo that is almost otherworldly in its precision in both response and intonation. The Norrköping Symphony Orchestra is an excellent partner for Jonason in the Lindberg work, but the Vamlingbo Quartet truly shines in the Golijov. The quartet matches Jonason’s precision playing, and performs with such ferocity at times that the listener will forget there are only five musicians performing. The recorded sound is excellent and the five-channel surround sound is especially effective in the Lindberg.

This release is a “must have” for clarinetists and will inspire everyone to hear the music as Golijov describes it: “An art that springs from and relies on our ability to sing and hear, with the power to build castles of sound in our memories.”

Christopher Ayer

Perpetuum Mobile. Trebuchet Wind Trio: Andra Bohnet, flute, piccolo, alto flute, bass flute, whistles, Irish flute, Scottish smallpipes; Rebecca Mindock, oboe, English horn, bass oboe, bassoon, contrabassoon; Kip Franklin, clarinet, E-flat clarinet, bass clarinet; Jasmin Arakawa, piano. C. Saint-Saëns: Caprice sur des airs Danois et Russes, Op. 79; P. Wharton: Sonatina (2015) for flute, oboe and clarinet and 4 in Motion (1993); J. Damase: Quartet for flute, oboe, clarinet and piano (1991); C. Huguenin: Trio No. 1 – Style Ancien, Op. 30; M. Praetorius: “Bransles de Villages” from Terpsichore. Flying Frog Music FF2016. Total time: 66:51. Amazon, iTunes and CDBaby

A new compact disc by the Trebuchet Wind Trio features a distinctive program of music from the Renaissance through the 21st century. The members of the trio, along with pianist Jasmin Arakawa, hold teaching positions at the University of South Alabama. The disc opens with Camille Saint-Saëns’ Caprice sur des airs Danois et Russes, Op. 79, for flute, oboe, clarinet and piano. Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) presented a series of concerts in Russia in 1887, and included Russian and Danish airs in the Caprice as an hommage to Tsarina Maria Feodorovna, the daughter of the King of Denmark, who married into the Russian Court. The work opens with dramatic and free “tempest-in-teapot” moments in the minor mode followed by the plaintive themes of the airs. The work concludes with an extended dance-like section. Trebuchet and pianist Arakawa beautifully capture these varied moods with warmth of tone and dramatic technique, when needed, and an elegant, single-minded interpretation.

A new compact disc by the Trebuchet Wind Trio features a distinctive program of music from the Renaissance through the 21st century. The members of the trio, along with pianist Jasmin Arakawa, hold teaching positions at the University of South Alabama. The disc opens with Camille Saint-Saëns’ Caprice sur des airs Danois et Russes, Op. 79, for flute, oboe, clarinet and piano. Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) presented a series of concerts in Russia in 1887, and included Russian and Danish airs in the Caprice as an hommage to Tsarina Maria Feodorovna, the daughter of the King of Denmark, who married into the Russian Court. The work opens with dramatic and free “tempest-in-teapot” moments in the minor mode followed by the plaintive themes of the airs. The work concludes with an extended dance-like section. Trebuchet and pianist Arakawa beautifully capture these varied moods with warmth of tone and dramatic technique, when needed, and an elegant, single-minded interpretation.

The Sonatina for flute (piccolo, penny whistle), oboe (English horn), and clarinet (bass clarinet) (2015), is by American composer Philip Wharton (born 1969). This work is the most harmonically incisive on the disc. Wharton successfully enhances texture throughout the work by having the performers double on other instrumental family members. The opening “Scamper” moves the score from bass clarinet, flute, and oboe, to soprano clarinet, oboe and piccolo by the movement’s conclusion. The middle “Lullaby” is elegiac and features the English horn, and in the final “Trifle” movement, the penny whistle makes a raucous appearance. The piece allows the members of Trebuchet to showcase their flexibility in adroitly shifting from one instrument to the next.

Jean-Michel Damase (1928-2013) was an admirer of fellow French composers Fauré and Ravel, whose influences can be felt in his Quatour pour flute, hautbois, clarinette et piano (1991). Once again, the musicians present a unified and deft interpretation. The opening Moderato movement features gorgeous instrumental colors, sparkling melodies, and lush harmonies. The Allegretto is of great wit and charm with lively melodies and racing figurations. The Andante is a Poulenc-ian moment of sweetness and melancholy while an alluring Allegro vivace concludes the work.

Swiss composer Charles Huguenin (1870-1939) was a choirmaster and a composer and publisher of Protestant religious music. His Trio No. 1 – Style Ancien, Op. 30, includes four short Baroque dance movements and showcases the Trebuchet trio in a new configuration: flute, clarinet and bassoon.

A second work by Wharton on the disc is titled 4 in Motion for flute (piccolo), oboe, clarinet and piano (1993). This accessible and tonal work exhibits an intensive rhythmic style. “Parody March” hints at the march in Stravinsky’s Soldier’s Tale, while “Haunted Echoes” features dolorous, lyrical solo statements answered by sometimes frantic proclamations by the tutti ensemble. “Perpetuum Mobile” is the final movement, and is the namesake of the disc. It is the technical tour de force of the disc, featuring continuous 16th-note patterns passed among the ensemble’s members.

Michael Praetorius (1571-1621) was a German Renaissance composer of sacred vocal music. The Terpsichore is his sole instrumental work and one of the few surviving instrumental works from the period. Here, Trebuchet shows off its virtuosity in another way through the magic of multitrack recording, which provides greater textural color and variety than possible in a live performance by the trio. In its arrangement of “Branseles de Villages” in five parts, passages of mixed ensemble alternate with passages of consorts of instrumental groups (all played by a single member of the trio) on flutes, double reeds and clarinets. Among the more exotic instruments featured include alto flute, bass flute, Scottish smallpipes and contrabassoon.

Overall, this is a full-bodied listening experience, not only because of the artistry of the individual members and their collaborative effort, but also because of the virtuosity displayed by the members of the trio in the mastery of entire families of instruments. The widely varied textures create an ever-changing palette of colors throughout the disc, always surprising

and engaging.

Scott Locke

Fragmented Visions. Teppo Salakaa, contralto clarinet; Victa Rain, piano. T. Salakka: Mustan kuun lauluja (Songs of a Black Moon); H. Dahlgren: 2 Moment musicaux; H. Eklund: 4 pezzi brevi; J. Vejslev: Solo for Bass Clarinet No. 2, Op. 105; E. von Koch: Monolog Nos. 3 and 5; V. Rain: Luodot; A. Piazzolla: Oblivion; H. Sarmanto: Waltz for a Little Girl. Artist produced. Total time 66:59. [email protected]

Finnish clarinetist Teppo Salakka has pioneered into the low clarinet world with Fragmented Visions, the first recording of solo contra-alto clarinet repertoire. “Which repertoire is that?” you may be asking. There is indeed a limited amount to choose from, and as such the album features transcriptions of works by Nordic composers originally written for clarinet, bass clarinet or bassoon, with the exception of one piece composed by Salakka himself for contra-alto clarinet, Mustan Kuun Lauluja (Songs of a Black Moon), the movements of which are interspersed throughout the album.

Finnish clarinetist Teppo Salakka has pioneered into the low clarinet world with Fragmented Visions, the first recording of solo contra-alto clarinet repertoire. “Which repertoire is that?” you may be asking. There is indeed a limited amount to choose from, and as such the album features transcriptions of works by Nordic composers originally written for clarinet, bass clarinet or bassoon, with the exception of one piece composed by Salakka himself for contra-alto clarinet, Mustan Kuun Lauluja (Songs of a Black Moon), the movements of which are interspersed throughout the album.

The disc opens with the first movement of Salakka’s piece, “Musta kuu nousee (The Moon is Rising),” which showcases the low register of the contra-alto clarinet with a brief foray into the upper range. Salakka has a deep, rich tone and does not suffer from the common contra-alto problem of stuffy middle and upper registers. The second movement is the fourth track, “Kehtolaulu (Lullaby).” This is actually a duet, both parts recorded by Salakka. It is a lovely melody, expressively performed and a highlight of the album. The third movement, “Tansii (Dance),” is another duo with the voices following each other in thirds. The writing is such that the duo almost sounds like a quartet, as the parts jump between playing a bass line and then a higher register melody, as in Theo Loevendie’s solo bass clarinet piece Duo. The final movement, “Aamu (Morning),” appears as track 15 and revisits the melodic material from the first movement.

The second piece is Hans-Erik Dahlgren’s Moment musicaux, originally written for clarinet. The first movement, “Etyd,” again features the lowest register and translates well onto the contra-alto. The second movement, “Fragmentariska bilder,” was written for and dedicated to Salakka and opens with air and key-click sounds that I imagine sound even better here on the large, resonant instrument than on clarinet, however some of the fast, large-interval, staccato notes that follow are a bit lumbering. The piece ends with a sudden shift into a folk melody that, while lyrically played and pleasant to listen to, seems to catch me off guard every time. The next work is 4 pezzi brevi for clarinet from Hans Eklund which shows off both the dynamic and pitch range of the instrument. Jakob Vejslev’s Solo for Bass Clarinet No. 2, Op. 105, follows and Salakka demonstrates that the contra-alto clarinet is just as viable as a solo instrument as the bass clarinet. The next offerings are two compositions from Erland von Koch, Monolog 3 for clarinet and Monolog 5 for bassoon, which draw from Swedish folk music.

The next piece is the first with piano, Luodot for bassoon, composed and performed by Victa Rain, and inspired by folk melodies. Piazzolla’s Oblivion is the only non-Nordic composition on the album. Salakka moves around the beautiful melody with such lyrical and technical ease that one forgets he is playing an instrument 50 percent larger than the modern bass clarinet. The album ends with Waltz for a Little Girl, a jazz ballad by Heikko Sarmanto. Salakka takes a short solo, but Rain’s jazz chops are featured more prominently here.

Overall, Teppo Salakka has brought us a nice album promoting the contra-alto clarinet and Nordic composers, and I hope to hear more of both in the future.

Jason Alder

Pearls and Thrills. Milan Milosevic, clarinet and tárogató; Cary Chow, piano; Jesse Read, bassoon; Ryszard Tyborowski, guitar; Nenad Zdjelar Keza, bass; Zoran Kiki Caušević, percussion. B. Bartók: Romanian Folk Dances, Sz. 56 (arr. Z. Székely/M. Milosevic); J. Vilmos: Tárogató, Book 1; B. Milošević: Girl’s Dance (arr. M. Milosevic); S. Robinovitch: Klezmer in Granada (arr. M. Milosevic); M. Glinka: Trio Pathétique. Artist produced. Total time 37:17. Amazon, iTunes and CDBaby

This album truly is a collection of Pearls and Thrills including works by Béla Bartók, Jäger Vilmos, Božidar Milošević, Sid Robinovitch and Mikhail Glinka. Clarinetist Milan Milosevic serves as director of the music department and clarinet instructor at Vancouver College. He previously performed with the Belgrade Philharmonic Orchestra. This album was recorded in the Roy Barnett Recital Hall and Studio at the University of British Columbia School of Music and is balanced with great clarity by engineers David Simpson, Alexander Korchev and Predrag Milanović.

This album truly is a collection of Pearls and Thrills including works by Béla Bartók, Jäger Vilmos, Božidar Milošević, Sid Robinovitch and Mikhail Glinka. Clarinetist Milan Milosevic serves as director of the music department and clarinet instructor at Vancouver College. He previously performed with the Belgrade Philharmonic Orchestra. This album was recorded in the Roy Barnett Recital Hall and Studio at the University of British Columbia School of Music and is balanced with great clarity by engineers David Simpson, Alexander Korchev and Predrag Milanović.

Béla Bartók’s Romanian Folk Dances was arranged by Zoltán Székely and Milosevic. These short dance pieces were originally written for piano and later transcribed by Bartók for a small orchestra. Milan Milosevic adapted these pieces for this recording for clarinet and tárogató, alternatively showing the relationship between the two instruments. Milosevic and pianist Cary Chow give a delightful performance of the six dances: “Stick Dance,” “Waistband Dance,” “In One Spot,” “Hornpipe Dance,” “Romanian Polka” and “Quick Dance.”

Jäger Vilmos has appeared as a virtuoso performer on the tárogató, and published at least two volumes of melodies, which were used as etudes for mastering the instrument. The tárogató melodies on this album are from Vilmos’s Book 1 and include the exciting “Kurucz Piculas Dala,” the soulful “Bertok Nota” and “Jaj De Magas.” Milosevic demonstrates incredible control and mastery of the tárogató.

Bozidar Milošević’s Girl’s Dance is arranged by Milan Milosevic. He is joined by Ryszard Tyborowski on classical guitar, Nenad Zdjelar Keza on double bass and Zoran Kiki Caušević on percussion. This begins with a beautiful slow melody and picks up intensity, which demonstrates Milosevic’s mastery of this style.

Percussionist Zoran Kiki Caušević and bassoonist Jesse Read join Milosevic for his arrangement of “Mit Gefihl” from Sid Robinovitch’s Klezmer in Granada. Robinovitch’s works are widely performed and published, and though rooted in folk and ethnic sources, are never far from the idioms of today. As the program notes state, this music fuses the dark and sultry atmosphere of the tango with a sometimes tongue-in-cheek reference to the traditional itinerant band of accordion, fiddle and clarinet nearly always present at a Jewish wedding or other celebration.

The final work in this collection is Mikhail Glinka’s Trio Pathétique for clarinet, bassoon and piano. “I knew love only by the sorrow which it causes…” is inscribed on the title page of the manuscript of Glinka’s trio, aptly subtitled “Pathétique.” Milosevic, Read and Chow give a stunning performance of this passionate work.

Milosevic and his colleagues have recorded a bountiful cornucopia of diverse repertoire. Their performances display a refreshing breadth of expression. Highly recommended!

Julianne Kirk Doyle

There Is Never No Light. Joshua Rubin, clarinet and bass clarinet; Cory Smythe, piano. M. Diaz de Leon: The Soul Is The Arena; M. Davidovsky: Synchronisms No. 12; S. Farrin: Ma Dentro Dove; I. Baca Lobera: Salto Cuantico; J. Rubin/C. Smythe: Toast; O. Wilson: Echoes. Total time: 57:29. Amazon, iTunes and CD Universe

Though not a new release per se, Joshua Rubin’s fantastic 2014 record There Never is No Light remains an excellent listen for those interested in works for clarinet and electronics. Across the disc’s six compositions, Rubin displays robust, emotional and conscientious playing in a variety of situations, utilizing numerous contemporary techniques. Rubin is affiliated closely with the Chicago-based International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE) and has served as a founding member since its 2001 inception.

Though not a new release per se, Joshua Rubin’s fantastic 2014 record There Never is No Light remains an excellent listen for those interested in works for clarinet and electronics. Across the disc’s six compositions, Rubin displays robust, emotional and conscientious playing in a variety of situations, utilizing numerous contemporary techniques. Rubin is affiliated closely with the Chicago-based International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE) and has served as a founding member since its 2001 inception.

Blazing electronics and pointed bass clarinet playing jest the listener immediately in the work’s opening track, The Soul is the Arena (2010), a work written by Rubin’s ICE colleague Mario Diaz de Leon. I am reminded at times, particularly by the electronics, of earlier-era 8-bit and 16-bit video game soundtracks and sound effects. Rubin’s bass clarinet playing is powerful and resolute.

The disc’s second track is a highly valuable recording of Mario Davidovsky’s Synchronisms No. 12, a prominent composition for clarinet and fixed media from 2006. It is the most recent of the series of Synchronisms written for a variety of instruments. Rubin’s playing is truly excellent, with the outstanding timing necessary to align the clarinet part with the fixed electronic media played in the composition, as well as an attempt to match timbre with the occasional B-flat clarinet sounds heard in the fixed electronic media part. Should students or professionals endeavor to play this magnificent composition, Rubin’s recording is essential as a reference.

Next is Suzanne Ferrin’s Ma Dentro Dove (2010), a work for solo B-flat clarinet and resonating body. Rubin’s energy is ceaseless throughout this work of approximately eight minutes. The resonating body’s effectiveness is crystal clear, as Rubin sounds like he is playing in a room of immense magnitude. A variety of dissonant multiphonics and flutter tongue techniques are employed.

The longest track on the album is a 17-minute recording of Ignacio Baca-Lobera’s 2011 composition Salto Cuántico for prepared clarinet and electronics. The work is often angular and multi-tiered in timbre and demeanor. As demonstrated in the works by de Leon and Davidovsky, Rubin is well versed in interacting successfully with computer-generated sounds. Mastering and production on this track is especially effective, and at no point is a meaningful clarinet or electronic gesture ever lost to poor balance or other adjustments. This work’s length will likely stretch listeners that are unfamiliar with the genre, but that is no comment on Rubin’s playing or his production team.

Rubin is joined by pianist Cory Smythe for Toast, a 2012 collaborative composition by the two performers. This shorter work has lengthy gradient electronic sounds and the interplay of prepared piano and long tones from Rubin’s clarinet playing. The dissonances in the work are particularly frictional and biting at times, and make for a very interesting listen.

The album’s final work is Olly Wilson’s Echoes, a work for clarinet and tape from 1974. The piece alternates between stretches of solo clarinet playing and collaboration between tape and performer, and Rubin’s attention to timing is as excellently detailed as in the Davidovsky. The piece’s longitudinal approach to increasing intensity makes for very engaging listening with a number of sonic surprises, and is an excellent choice to close the album.

Joel Auringer

Hindemith, Van der Roost, Strauss. Eddy Vanoosthuyse, clarinet; Central Aichi Symphony Orchestra, Sergio Rosales conductor. Paul Hindemith: Clarinet Concerto; Jan Van der Roost: Clarinet Concerto; Richard Strauss: Romanze in E-flat. Naxos 8.579010. Total time 57:31. Naxos

In this 2017 release by the Belgian clarinetist Eddy Vanoosthuyse, we have the attractive pairing of the Hindemith Concerto (something old) with the Van der Roost Concerto (something new), rounded out with the miniature gem Romanze (something sweet) by Richard Strauss. The accompanying ensemble, the Central Aichi Symphony Orchestra (Japan), is convincingly led by Venezuelan conductor Sergio Rosales.

In this 2017 release by the Belgian clarinetist Eddy Vanoosthuyse, we have the attractive pairing of the Hindemith Concerto (something old) with the Van der Roost Concerto (something new), rounded out with the miniature gem Romanze (something sweet) by Richard Strauss. The accompanying ensemble, the Central Aichi Symphony Orchestra (Japan), is convincingly led by Venezuelan conductor Sergio Rosales.

The post-war Hindemith Concerto was first recorded in 1958 by the iconic French clarinetist, late to the role of soloist, Louis Cahuzac. Written on commission for Benny Goodman in 1947, it was premiered by him (but never recorded) in 1950 with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra. Having a contemporary interpretation by Vanoosthuyse with an updated sonic clarity brings new life and light to this underperformed and often underappreciated work.

While Hindemith’s contrapuntal writing can be difficult to sort out through the dense orchestration, Vanoosthuyse and the orchestra do a fabulous job in maintaining clarity in all of the interwoven lines. The clarinet soars above the orchestra with a limpid quality that belies the inherent technical and balance issues, and the stylistic contrasts of the four movements are perfectly and convincingly captured. The clarinet playing is spot-on throughout, and the richly played and projected orchestral solo lines bring awareness to the listener of the compositional artistry of this concerto.

Jan Van der Roost (b. 1956) is a Belgian-born and -trained composer, conductor and clinician. His works, both large and small, range from full orchestra, band and brass band, through chamber and solo pieces. His Clarinet Concerto was premiered by Vanoosthuyse and the Utah Philharmonia on December 10, 2008, and its Japanese premiere took place in 2015, the same week this recording was made. With an unusual two-movement structure, Van der Roost sets out to establish the “serious side of the clarinet” (composer’s words) in the first movement, “Doloroso e contemplativo,” through the use of long melodic lines and the staging of the orchestra as an equal partner. Van der Roost’s use of a compelling and varied orchestral palette gives an attractive cinematic feeling to the work, leaving an impression of an episodic rather than thematic approach.

The second movement, “Giocoso e con bravura,” focuses on the agility of the solo instrument, as an “exceptional dexterity is required of the soloist as the clarinet is asked to sing, weep and joke” according to Van der Roost’s program notes. I could not have characterized it any better, and Vanoothuyse manages these significant hurdles with aplomb. This is an extremely accessible and attractive work, for which this reviewer thinks that many repeat performances are justified. Now if we could only convince the concert presenters of this!

Richard Strauss wrote his Romanze at the precocious age of 15, at which point it was already his Opus 27. Entirely pleased with his youthful efforts, Strauss wrote to a friend, “I have been very industrious, composing a romance in E-flat major for clarinet and orchestra, which has turned out quite well.” It indeed is an attractive work, well done on this recording; Vanoosthuyse sells it with a heartfelt lyricism. One only wishes that Strauss had made this 7-minute gem part of a larger work for our instrument.

This is a must-own volume of important and highly accessible solo literature with orchestra. As always, one values those recordings that are both vivid and accurate in their execution, but also have that magical sense of spontaneity. This is a disc to value for all of those qualities, with excellent liner notes.

Howard Klug

Comments are closed.