Adjusting Saxophone and Clarinet Reeds

(Originally published in 2011)

by Peter Spitzer

I’ve been reading some interesting books on reed adjustment: The Single Reed Adjustment Manual by Fred Ormand, Selection, Adjustment and Care of Single Reeds by Larry Guy, The Saxophone Reed – The Advanced Art of Adjusting Single Reeds by Ray Reed, Perfect A Reed…and Beyond by Ben Armato, and the Handbook for Making and Adjusting Single Reeds by Kalmen Opperman. There are also some good pages on the subject in The Art of Saxophone Playing by Larry Teal. My motivation, of course, has been to try to address the eternal problem of how to find a good reed.

Reading these books has been an enlightening experience; the authors all have real expertise. There is much agreement, some disagreement, and each has a somewhat different slant.

What makes a reed “good” or “great” is highly personal. Every player has his or her own combination of embouchure, mouthpiece, and instrument. Most importantly, each player has a personal concept of a desirable sound. There is no way that a commercial reed maker could satisfy every player’s individual needs. Also, quality control at the factory could be better. Thus, unless you are willing to throw out a lot of reeds in the search for a “good” one, adjustment is a worthwhile skill to develop.

This article has four parts:

- A practical “how-to” summary of reed adjustment, based on my own experience, combined with information I’ve picked up from these books;

- Some notes about reed-adjusting lessons with Joe Allard, from my friend Robert Kahn;

- A brief review of each of the books; and

- Some observations on areas of agreement and disagreement.

Basic reed adjustment

This section really only “scratches the surface” (so to speak). I have had to leave out a large amount of information, in the effort to be concise.

Our topics here are: Minimum Tools, Reed Selection, The Breaking-in Process, Vamp and Tip Adjustment, Warps, Weather, and Continuing Adjustment.

Minimum tools:

- Reed knife – I like a beveled-edge knife (they come in left- or right-handed). Keep the knife very sharp.

- Sharpening stone – should have a coarser and a finer side.

- Sandpaper – #400 and/or #600 “wet-or-dry.” The #400 is best for larger reeds (alto/tenor/bari sax), #600 is best for clarinet and soprano sax reeds (or for fine work, like near the tip, on all sizes of reeds). Using scissors, cut one of the #400 (or #600) sheets into quarters. Save one of the quarters for sanding the table (underside) of the reed, when necessary. Cut one of the other quarters into small strips about one quarter inch wide and 1 1/2 inches long; cut one end of each strip diagonally, into a point. Use these strips for precise work, instead of scraping with a reed knife. Make a lot of them; they wear out quickly (credit to Larry Guy for the strips idea).

- A flat surface – a small glass or plastic plaque, 4” x 6” more or less.

- A reed clipper (for clarinet, alto, tenor, or bari).

Super-minimum tools (suggested for beginners): One sheet of #400 or #600 wet-or-dry sandpaper and a very flat surface, like a 4″ x 6″ sheet of plastic. As mentioned above, use scissors to cut the sheet into quarters. Save one of the quarters for sanding the table (bottom) of the reed, when necessary. Cut one of the other quarters into small strips about one quarter inch wide and 1 1/2 inches long; cut one end of each strip diagonally, into a point. Use these strips instead of scraping with a reed knife. Make a lot of them.

Thank you to Peter Spitzer for sharing this article with us!

Click the button below to read the full article which continues with discussing:

- Reed Selection

- Breaking-in Process

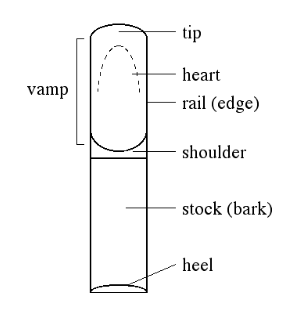

- Vamp and Tip Adjustment

- Warps

- Weather

- and more!

Comments are closed.