Originally published in The Clarinet 45/2 (March 2018). Printed copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

by Katherine Palmer and Michele von Haugg

Clarinets for Conservation (C4C) – also known as Daraja Music Initiative – is a U.S.-based non-profit that provides an innovative summer program in the Kilimanjaro region of Tanzania. C4C utilizes the transformative power of music education to promote the protection of natural resources and environmental sustainability. African blackwood, also known as grenadilla or mpingo, is the national tree of Tanzania and is used in the construction of clarinets, oboes and other Western European instruments. The tree is commercially endangered and very few Tanzanians know of the tree’s musical connection. Operating as a grassroots organization, C4C has offered music and environmental education to a select group of secondary and primary students for the past seven summers through daily music instruction and weekly conservation field trips. In an area fraught with environmental issues related to deforestation and fresh water access, drawing a tangible connection between the national tree and the universal art form of music encourages the community to embrace mpingo in a new way.

Building Musical Bridges

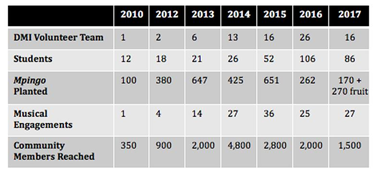

For seven previous summers, Clarinets for Conservation has traveled to the Kilimanjaro region of Tanzania in order to actively engage students and the community with the power of music. C4C was founded in 2010 by Michele Von Haugg when she traveled to Tanzania with a suitcase of 12 clarinets and the idea to connect the musical product with the product source. Over the years, the program has grown to include general music, recorders, strings and other wind instruments. For this reason, C4C created an umbrella organizational title of Daraja Music Initiative (DMI) to better encompass its musical reach. Daraja means “bridge” in Swahili.During seven summers of operation, DMI has impacted over 300 students and 14,000 community members. DMI has also planted a significant number of mpingo trees in the region, while highlighting the importance of sustainability practices for a better environment. As school and community food needs have become more pronounced, we have also been supplementing our tree plantings with fruit trees.

For seven previous summers, Clarinets for Conservation has traveled to the Kilimanjaro region of Tanzania in order to actively engage students and the community with the power of music. C4C was founded in 2010 by Michele Von Haugg when she traveled to Tanzania with a suitcase of 12 clarinets and the idea to connect the musical product with the product source. Over the years, the program has grown to include general music, recorders, strings and other wind instruments. For this reason, C4C created an umbrella organizational title of Daraja Music Initiative (DMI) to better encompass its musical reach. Daraja means “bridge” in Swahili.During seven summers of operation, DMI has impacted over 300 students and 14,000 community members. DMI has also planted a significant number of mpingo trees in the region, while highlighting the importance of sustainability practices for a better environment. As school and community food needs have become more pronounced, we have also been supplementing our tree plantings with fruit trees.

The organization operates in three locations (Majegno Primary School, Korongoni Secondary School and TPC Sugar Plantation) and has hopes to expand to a fourth location at a nearby university, Tumaini University Makumira, in upcoming summers.

About Mpingo

Dalbergia melanoxylon, or mpingo tree

Dalbergia melanoxylon, the scientific name for mpingo, boasts a carbon-rich heartwood that turns black when the tree is fully mature. The tree, coveted by instrumentalists and wood turners around the globe, has recently been listed as a protected resource through the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). [See James Sullivan’s article on CITES regulations. Ed.]

An African blackwood tree will grow for a minimum of 60-200 years before being ready for harvest. A small, spike-covered shrub, the tree seedling grows easily throughout sub-Saharan Africa, yet the mature trees are quickly disappearing. In the first several years of growth, the tree grows low like a bush, spreading its branches outwards, providing fodder for elephants and giraffes.

DMI students planting mpingo

As the blackwood nears 50 years, the bush-like seedling begins to stretch straight upwards and resembles the massive tree that will eventually provide raw material for clarinets, oboes, and hand-carved pieces. The heartwood continues to hungrily ingest carbon from the atmosphere, turning dark and spreading outwards, replacing the soft, light sapwood with an impenetrable black heart. So resilient is this mature tree that it becomes resistant to even the wildfires of the savannah, providing the first food for the animals when all else has perished.

Forests are often called the lungs of the earth, due to carbon dioxide absorption and the oxygen they provide to the world. The National Arbor Day Foundation notes that one fully mature tree can provide enough oxygen for a family of four to breathe for an entire year. Botanists believe that blackwood forests absorb far greater amounts of carbon dioxide, and that perhaps mpingo provide as much as 10 times more oxygen than other trees.

Sustaining the Earth through Music

Collegiate volunteer Katie Kessler teaching a beginning clarinet student

DMI currently has trees planted at local schools, orphanages, community centers and government buildings. The mpingo seedlings are strong and planted under the direction of Samweli Mochiwa, the owner-operator of Kiviwama Tree Nursery. In order to strengthen our existing nurseries and create more sustainable nurseries, DMI aims to partner with the Mpingo Conservation & Development Initiative (MCDI), a NGO located in southern Tanzania that promotes community-based forest management.

Gary Sperl teaching beginning clarinet at Korongoni Secondary School

Teaching secondary students in Tanzania to play musical instruments empowers them by improving problem-solving skills, facilitating self-sufficiency and by providing a healthy creative outlet. Students and teachers also take part in innovative interdisciplinary performances and tree plantings throughout Kilimanjaro to help connect instruments and the tree they are made of, mpingo, with the community – therefore fostering the responsible use of natural resources and a sustainable future.

Each summer, the program is made possible through volunteers and donations. You can find more information about the DMI organization at www.darajamusicinitiative.org

New clarinet students performing in concert

About the Writers

Katherine Palmer is the executive director of Daraja Music Initiative and Curator of Education at the Musical Instrument Museum in Phoenix. She also teaches at Paradise Valley Community College and Arizona State University.

Michele Von Haugg founded Clarinets for Conservation and currently resides in San Antonio, Texas where she is currently a clarinetist with the Air Force Band of the West. Her performance career began with the Air Force Band of Liberty in Massachusetts.

Comments are closed.