Originally published in The Clarinet 52/2 (March 2025).

Copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

2023 ICA Research Competition Winner

Enhancing Rhythmic Literacy in Applied Clarinet Lessons

This award-winning article from the 2023 ICA Research Competition presents results of a survey about teaching students with learning differences, and provides excerpts from a pedagogy guide to help instructors address students’ challenges in rhythmic literacy.

by Shannon McDonald and Cecilia Kang

INTRODUCTION

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, during the 2022-2023 academic year, 15% of all public-school students in the United States (ages 3-21) received special education services under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). This increased from 6.4 million to 7.5 million, an all-time high, between 2012 and 2022.1 Though 94% of pre-college students diagnosed with specific learning disabilities sought accommodations, only 17% of those students continued to receive accommodations in college.2

This data, combined with researchers’ experiences and initial discussions with other music community members—including the International Clarinet Association’s Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Access Committee—inspired a study investigating music educators’ experiences with students that have prolonged rhythmic literacy challenges. For the purpose of this study, we define rhythmic literacy as deciphering and performing written Western rhythmic notation. The study did not explicitly focus on students with learning differences; we gathered data from private lesson instructors in higher education who had worked with students who had frequent difficulty deciphering rhythmic notation, regardless of whether they identified as neurotypical or neurodivergent. This study does not focus solely on students with learning disabilities and does not consider all students that struggle with rhythmic literacy as having a learning disability.

The study was created to document the experiences of private lesson instructors and large ensemble directors working with students that have difficulty with rhythmic literacy. The study launched in the fall of 2022 and was spearheaded by Cecilia Kang. Co-investigators included Shannon McDonald, Simon Holoweiko (associate band director at Louisiana State University) and Jason Bowers (instructor of music education at Louisiana State University). This article focuses only on the data collected from clarinet instructors. The goal of this research was to gather anecdotal evidence and common resources that can assist private lesson instructors to understand, recognize, and accommodate students who struggle with rhythmic literacy.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

The research questions for this study were:

1. How often do music educators encounter college students who experience challenges deciphering Western rhythmic notation?

2. How often do music educators encounter students with learning differences that can directly affect their ability to decipher Western rhythmic notation?

3. What experiences do music educators have with collegiate music students who are challenged by deciphering Western rhythmic notation?

4. What resources do music educators use with students who experience challenges deciphering Western rhythmic notation?

5. What attitudes do music educators exhibit towards students who regularly experience challenges deciphering Western rhythmic notation?

LITERATURE REVIEW

General resources exist for improving rhythmic fluency, such as books aimed for classroom use, as well as etude books written for various instruments. Although many of these resources can help students learn and improve rhythm, very few include multiple pedagogical approaches for students who experience ongoing challenges with rhythmic literacy. There are also many resources for teaching neurodiverse students in the classroom, but very few address how to teach these learners specifically in the private lesson environment.

METHODOLOGY

In the fall of 2022, a survey was distributed to post-secondary music educators. The survey contained three sections: participant demographics, their experiences with students who have exhibited challenges with rhythmic literacy, and their attitudes towards students who experience challenges with rhythmic literacy. Participants were solicited through music organization member lists and school websites. Descriptive data were analyzed through Qualtrics (a commonly used qualitative analysis software tool).

PARTICIPANTS

The survey was completed by 113 music educators including band directors, choral directors, and private lesson instructors across the United States. Of the total survey respondents, 61 were applied teachers, and 17 of those were clarinet instructors.

The distribution of years of teaching experience in higher education was spread somewhat evenly across the participant pool. This may help account for any changes in educator attitudes towards learning differences that may take place over time. Studies conducted between 1975 and 1999 reported that teachers had a generally negative attitude towards the inclusion of special learners in their classrooms.3 In addition, Kimberly VanWheelden and Jennifer Whipple found in 2014 that music teachers held a more positive view of inclusion than they did 20 years prior.4

Participants were also asked about their training background in teaching students with special needs. Only one clarinet participant indicated completing a semester-long college class pertaining to teaching neurodivergent students, and only two clarinet teachers reported participating in professional development workshops pertaining to neurodiversity.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Research Question 1:

How often do music educators encounter college students who experience challenges deciphering Western rhythmic notation?

The majority of clarinet teachers reported that less than half of their students exhibit consistent difficulty deciphering rhythmic notation; however, six of the 17 clarinet teachers reported that they’ve seen an increase in students with this challenge. This indicates that there may be a trend of an increase in students who consistently struggle with rhythmic literacy.

Research Question 2:

How often do music educators encounter students with learning differences that can directly affect their ability to decipher Western rhythmic notation?

Table 1 illustrates how many clarinet teachers reported encountering students with a provider-diagnosed disability or disorder that could affect their ability to process rhythmic notation.

Table 1: Number of participants who reported encountering students with medically diagnosed disabilities/disorders

The most common diagnoses encountered by survey participants were anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), dyslexia, and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Anxiety can adversely affect academic performance, and students with anxiety may perform poorly on exams, assignments,7 and music performances. Dyslexia, the third most common disability reported by participants, is considered a reading disorder, and can make processing or reading written language difficult. For musicians, this can directly affect their ability to process written music.8

It is important that lesson teachers address difficulty with processing rhythms regardless of a diagnosis, since many students may exhibit neurodivergent characteristics without medical diagnoses. Furthermore, a significant number of students may be uncomfortable disclosing the diagnosis to their instructors at school.

There is clearly a need for more resources to aid private lesson teachers in understanding and accommodating neurodivergent learners. As stated above, most of the clarinet teachers surveyed had not received any training in teaching students with special needs.

Research Question 3:

What experiences do music educators have with collegiate music students who are challenged by deciphering Western rhythmic notation?

The most common challenge that clarinet lesson teachers reported addressing with their students was keeping a steady pulse, which they also reported as the most difficult to address. A majority (88%) reported already utilizing a metronome with their students. This could indicate that other tools are needed to help with this concept. Some students may struggle with hearing the metronome while they perform. Many metronome apps have special features including vibration or visual blinking lights to indicate the beat; however, less than 35% of teachers used blinking lights and less than 18% used vibration with their students.

Using color with individuals who have dyslexia is a common accommodation.9 Since dyslexia is one of the most frequently diagnosed learning disabilities,10 it may be expected that lesson teachers would use color accommodations (including colored paper, colored ink/highlighters, or color overlays) with their students. However, only one participant had used highlighter, and no participants reported using colored paper or overlays. This could indicate that private lesson teachers are unaware of this accommodation commonly used for students with dyslexia.

Research Question 4:

What resources do music educators use with students who experience challenges deciphering Western rhythmic notation?

Based on the resource list provided in the survey, participants use various resources with their students who have difficulty deciphering rhythms, though no resource listed was consistently chosen by a large percentage of participants. This could indicate that a private lesson resource geared towards students who consistently struggle with rhythmic literacy does not exist. One participant stated, “Traditional teaching materials do not usually contain enough rhythmic variety to address deep-seated rhythmic problems in students.”

Research Question 5:

What attitudes do music educators exhibit toward students who regularly experience challenges deciphering Western rhythmic notation?

Almost half (47%) of participants agreed that students who consistently have challenges deciphering rhythmic notation could be successful performers. In addition, 35% agreed that these students could be successful music educators. In college settings, it is often the responsibility of the private lesson teacher to find resources to help their students to overcome rhythmic challenges.

Another consideration is that there can be a stigma for students to discuss their challenges with their professors. According to the survey, 41% of participants observed that students who struggle with rhythmic literacy are too embarrassed to seek help. One participant found that students responded negatively to the offering of rhythmic strategies:

The majority of my students arrive as freshmen with rhythmic music literacy issues. I offer all of them an array of strategies and the ones who choose to engage with at least some of the strategies often see improvement, but only when they actually utilize the strategies. Increasingly, students see the offering of strategies as a personal attack, but they also see rote instruction as a personal attack, so I’m left without any options.

Since it is possible for some of these students to “hide” in large ensembles and learn music by rote, it is important for private lesson teachers to recognize and normalize students who struggle in this area. One participant noted,

I think one of the biggest problems is that the students spend the majority (if not all) of their time pre-college playing in a band, and they simply follow others or play by ear. Having them play in chamber groups regularly would force them to become better with rhythm.

It is important that music educators collaborate to bring more awareness and break the stigma of openly discussing rhythmic literacy issues with their colleagues and students. This can eventually become a retention problem for music programs as a significant number of students may switch majors before they seek help. The majority of participants reported “sometimes” (eight of the 17 participants) or “often” (two of 17 participants) having difficulty retaining students who struggle with rhythms on a regular basis. A participant shared,

As a GA [graduate assistant] in my MM [master of music degree], I encountered a student with a learning disability who couldn’t read music but had a great ear. They wanted to switch to music education from music performance. My teacher at the time gave it to me to not deal with them anymore. In the second semester, and because of my immaturity, I told them to give up music and find something else to do. I tried everything in the list above, but nothing worked in this case. I would’ve done more, but I didn’t have any support from my teacher.

CONCLUSION

Clarinet lesson teachers may frequently encounter students who have consistent challenges deciphering Western rhythmic music notation, but teachers lack the knowledge or resources to help these students. It is crucial that music educators create learning environments that will help students feel comfortable discussing these challenges and seek appropriate help.

Considerations for Further Research

Another study is in progress that will focus on post-secondary music majors and their experiences with rhythmic literacy.

The authors plan to publish a pedagogical guide for clarinet private lesson teachers consisting of recommendations for common resources, repertoire suggestions, and pedagogical strategies in private lesson settings. See the next section for an excerpt from this planned pedagogical guide.

PEDAGOGY GUIDE

The goal of the forthcoming Pedagogy Guide is to assist clarinet lesson instructors in finding repertoire to specifically address different aspects of rhythmic literacy and provide targeted pedagogical strategies. This guide can be helpful for both beginning and veteran teachers seeking different teaching strategies. The repertoire discussed in this guide is suggested for advanced pre-college students and undergraduate music majors. Special efforts have also been made to include works by underrepresented composers, which are indicated in the repertoire index with an asterisk. The guide is organized into four sections: common resources, repertoire list organized by rhythmic challenge, repertoire list organized by composer name, and pedagogical master classes on selected clarinet repertoire.

Part I: Common Resources

Part I offers recommendations for general resources that include repertoire databases, lists of rhythmic training books and etudes, helpful apps, tools/devices, and rhythm video games.

Part II: Repertoire List by Rhythmic Challenges

Part II lists repertoire according to the rhythmic challenges found in the pieces. The purpose of this section is to aid instructors in finding repertoire that specifically addresses rhythmic challenges. Categories include asymmetrical meter, compound meter, consecutive 16th notes, dotted rhythms, cross rhythm, mixed meter, subdivision, syncopation, and triplets. More categories will be added as the guide is completed.

Part III: Repertoire List by Composer Name

Part III includes all pieces listed in Part II categorized by composer last name with their correlating rhythmic challenge listed. Both Part II and III denote pieces by composers of underrepresented populations with an asterisk.

Part IV: Repertoire Examples

This section outlines selected clarinet solo repertoire (with or without piano) with rhythmic challenges previously mentioned in Parts II and III. Suggested pedagogical approaches for rhythmic challenges are displayed with visual examples such as annotated scores, exercises, and diagrams. Suggestions for complementary etudes and solo pieces addressing similar rhythmic challenges are also listed for reference. See below for excerpts from Part IV.

EXAMPLE 1:

Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921)

Sonate, op. 167, I. Allegretto

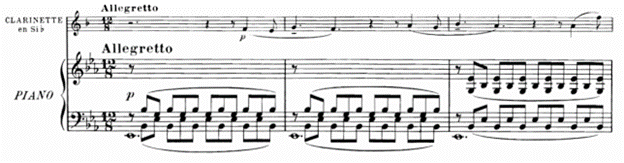

Description: The first movement of the Saint-Saens sonata is both lyrically beautiful and technical. Counting is fairly straightforward for a piece in a compound meter. The piano generally plays the eighth note beats, making this a great piece for students to solidify their counting in compound meter while performing a rewarding piece of core clarinet literature.

Rhythmic Challenges Addressed:

- Understanding the structure of compound meter

- Beginning a passage after a rest

- Tied Notes

Challenge No. 1: Understanding the structure of compound meter

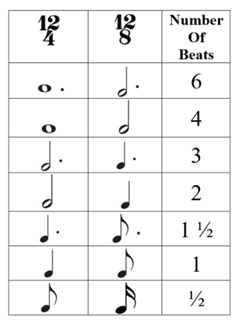

Figure 1: Chart of the relationship of beats between 12/4 and 12/8 time signatures

Pedagogical Strategies

- Make a chart showing the relationship between meters with a four and an eight on the bottom (see Figure 1).

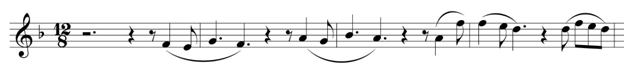

- Rewrite the clarinet part in 12/4 meter (see Figure 2).

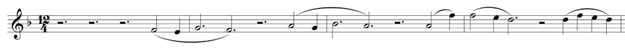

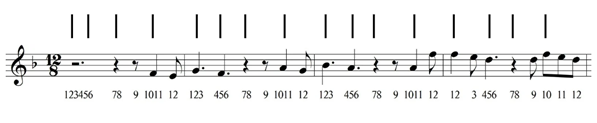

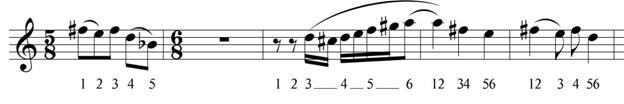

- Alternate counting rhythms in subdivided compound time (eighth note) vs. counting the dotted quarter note. Write in the eighth note counts and draw slash marks for the dotted quarter beats (see Figure 3).

- Score Study: Point out how the rhythm of the piano accompaniment aligns with the metronome on subdivided eighth notes (see Figure 4).

– Utilize the piano accompaniment (by playing or using a recording) as the metronome

– Sing, then play the clarinet part while clapping, marching, or listening to the piano part

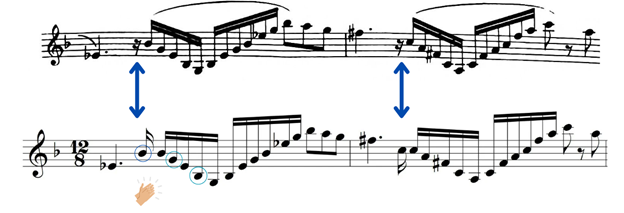

Challenge No. 2: Beginning a passage after a rest

Pedagogical Strategies

- Fill in the rest with an extra note; use the same note as the first written pitch (see Figure 5). Alternate playing the added note and playing the rest as written.

- Select anchor notes based on the eighth note pulse (every other note). Student sings, then plays the passage while the teacher claps the anchor notes (see blue circles in Figure 5). Alternate with the student (students claps, teacher sings/plays).

Figure 2: Camille Saint-Saëns Sonate, op. 167, m. 1-4; excerpt with original time signature and excerpt rewritten in 12/4

Figure 3: Saint-Saëns Sonate, m. 1-4; annotated with dotted-quarter-note beats slashed and eighth note beats written out in numbers

Figure 4: Saint-Saëns Sonate, m. 1-3, piano score

Figure 5: Saint-Saëns Sonate, m. 32-33; original score and rewritten part with added note in place of the rest

Challenge No. 3: Tied notes

(see Figure 6)

Pedagogical Strategies

- Break the tie; articulate the smallest subdivision of each longer note. Example: dotted quarter note subdivision = three eighth notes = six 16th notes (see Figure 7).

- Complete each exercise below for Figure 9 with the metronome first on the steady subdivision, then on the dotted quarter note beat

– Count and clap or tap feet

– Sing clarinet part

– Sing and finger clarinet part

– Play as written

Figure 6: Saint-Saëns Sonate, m. 43-52; tied notes denoted in brackets

Figure 7: Saint-Saëns Sonate, m. 45; original part and rewritten part without ties and with subdivisions of longer notes written out

Complementary Etudes for Compound Meter

- B. Bernards Rhythmical Studies for Clarinet, No.6, No. 15

- Friedrich Demnitz Elementary School for Clarinet, No. 10

- Gaetano Labanchi 35 Studies for Clarinet, No. 2, No. 3, No. 4

- Victor Polatschek Advanced Studies for the Clarinet, No. 14, No. 16

Complementary Repertoire for Compound Meter

- *Adolphus Hailstork (b. 1941) Three Smiles for Tracey, I.

- Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) Sonata in EÌMajor, II. Andante

- Gabriel Pierné (1863-1937) Canzonetta, op. 19

- Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Sonata No. 2, op. 120, II. Andante con moto

- *SiHyun Uhm (b. 1999) Collection of Korean Tunes, I. Arirang, III. Frog Song

- *Surendran Reddy (1962-2010) game I for lîla

EXAMPLE 2

SiHyun Uhm (b. 1999)

Collection of Korean Folk Tunes, I. Arirang

Score available at sihyunuhm.com.

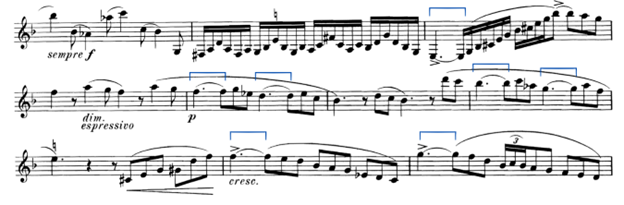

Description: SiHyun Uhm is a composer, pianist, and producer based in Los Angeles and South Korea.11 A Collection of Korean Tunes includes three iconic Korean folk melodies—Arirang, Ganggangsullae, and Frog Song. This piece honors the original folk tunes while also adding interesting rhythms and styles. This would be a lovely addition to any recital program.

Rhythmic Challenges Addressed:

- Mixed meter

- Cross rhythm

- Syncopation

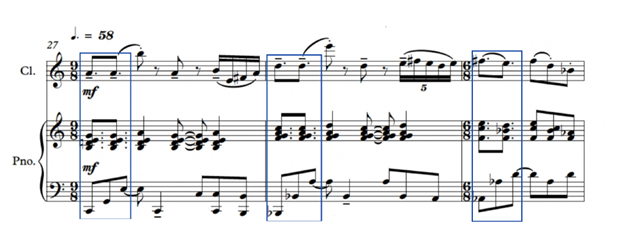

Challenge No. 1: Mixed meter

(see Figure 8)

Pedagogical Strategies

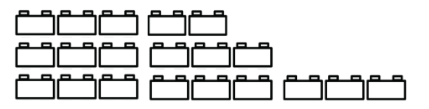

- Engage students visually and physically by utilizing manipulatives like building blocks or coins to show the construction of different meters (see Figure 9).

- Help the student feel the different pulses by counting/marching eighth notes and clapping the strong beats in each meter.

– In 5/8 – 123 45 or 12 345

– In 6/8 – 123 456 or 123456

– In 9/8 – 123 456 789

- Count/sing the rhythm of the passage while conducting. This will be especially helpful through the accelerated measures 22-24.

- Find the common subdivision (in this example, eighth notes)

– Write the eighth-note counts below the notes (see Figure 10)

– With the metronome on the eighth note beat, clap or say the beat

– Slowly conduct the eighth notes and speak or sing the rhythm

– Isolate the meter changes; practice the above suggestions from measure 16-17 and measure 21-22

Figure 8: SiHyun Uhm Collection of Korean Folk Tunes, I. Arirang, m. 16-28; meter changes are circled (used with permission from the composer)

Figure 9: Building blocks showing the construction of beats in 5/8, 6/8, and 9/8

Figure 10: Uhm, m. 16-25 with eighth note counts written underneath the notes

Challenge No. 2: Cross rhythm

(see Figure 11)

Pedagogical Strategies

- The rhythm explored in this passage is essentially a duplet against triplet. To get comfortable with two against three, try the following:

- “Hot Cup of Tea” game

– Tap the rhythm out on your knees while saying the phrase “Hot Cup of Tea.”

– Hot (both hands on both knees) Cup (2nd triplet – right hand on right knee) of (2nd duplet – left hand on left knee) Tea (3rd triplet – right hand on right knee). YouTube has many videos demonstrating this concept.

– March in duple while playing each note of a scale in triplet rhythm.

- Find the common subdivision (in this example, 16th notes)

– Write the 16th-note counts above the notes

– With the metronome set on the 16th notes, clap or say the rhythm

Figure 11: Uhm, Arirang, m. 27-29; cross rhythms annotated with brackets on clarinet and piano part

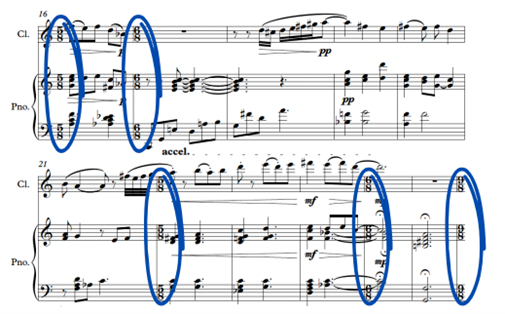

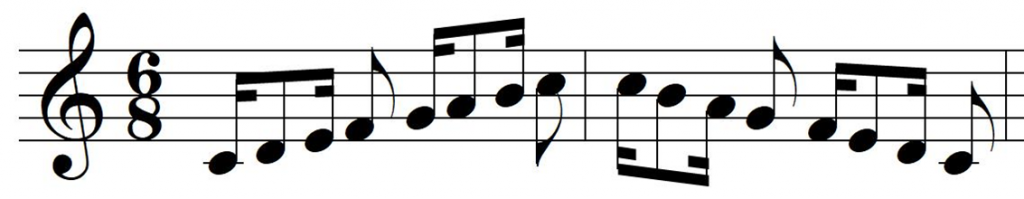

Challenge No. 3: Syncopation

(see Figure 12)

Pedagogical Strategies

- Practice scale figures on syncopated rhythms, continuing the patterns presented in Figure 13

- Rewrite the syncopated note (the eighth note in each figure) to two 16th notes

- Sing and play as written with the metronome on eighth-note and 16th-note subdivisions

Figure 12: Uhm, Arirang, m. 107-108, brackets around syncopated rhythms

Figure 13: Three scale exercises based on the syncopated rhythm of Uhm’s Arirang

Complementary Etudes for Mixed Meter

- Everett Gates Odd Meter Etudes

- *Jeanine Rueff 15 Etudes for Clarinet, Nos. 1, 3, 6, 9

- Marcel Bitsch Vingt Etudes, No. 7

- Paul JeanJean Etudes Progressives et Mélodique, No. 36

- Victor Polatschek Advanced Studies for the Clarinet, No. 27

Complementary Repertoire for Mixed Meter

- Gerald Finzi (1901-1956) Five Bagatelles II. Romance

- *Jean Ahn (b. 1976) Blush

- Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) Three Pieces I., III.

- Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) Sonata for Clarinet and Piano

- Malcolm Arnold (1921-2006) Sonatina for Clarinet and Piano, I. Allegro con brio

- *Theresa Martin (b. 1979) Sweet Feet

- Witold Lutoslawski (1913-1994) Dance Preludes I. Allegro molto, II. Andantino,

- III. Allegro giocoso, V. Allegro molto

Complementary Etudes for Cross Rhythm

- Everett Gates Odd Meter Etudes

- Marcel Bitsch Vingt Etudes, No. 7

- Rudolf Jettel Funf Grotesken, No. 4

Complementary Repertoire for Cross Rhythm

- Alban Berg (1885-1935) Vier Stücke, op. 5

- André Messager (1853-1929) Solo de Concours

- Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826) Concerto No. 2, op. 74, I. Allegro

- Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Première Rhapsodie

- Gerald Finzi (1901-1956) Five Bagatelles II. Romance

- *Germaine Tailleferre (1892-1983) Sonata for Clarinet

- Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Sonata No. 1, op. 120, I. Allegro appassionato

- Paul Jeanjean (1874-1928) Arabesques

- Robert Schumann (1810-1856) Fantasiestücke, op. 73

- *William Grant Still (1895-1978) Romance

Complementary Etudes for Syncopation

- Astor Piazzolla Tango Etudes, No. 1

- B. Bernards Rhythmical Studies for Clarinet, No. 7, 10, 17

- Gaetano Labanchi 35 Studies for Clarinet, No. 5

- Grover C. Yaus 40 Rhythmical Studies, No. 20

- Jean Xavier Lefevre 60 Exercises, No. 3, 7

- Rudolf Jettel 10 Etudes, No. 1

Complementary Repertoire for Syncopation

- Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826) Concerto No. 2, Op. 74, III. Rondo; Alla Polacca

- Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Sonata No. 2, Op. 120, III. Andante con moto

- Malcolm Arnold (1921-2006) Sonatina for Clarinet and Piano, I. Allegro con brio

- *Surendran Reddy (1962-2010) game I for lîla

ENDNOTES

1 “Students with Disabilities,” National Center for Education Statistics, last modified May 2024, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cgg/students-with-disabilities.

2 “Understanding the Issues,” National Center for Learning Disabilities, last modified May 16, 2024, www.ncld.org/join-the-movement/understand-the-issues.

3 Laurie P. Scott, et al., “Talking with Music Teachers About Inclusion: Perceptions, Opinions, Experiences,” Journal of Music Therapy 44, no. 1 (Spring 2007), 38-56.

4 Kimberly VanWeelden and Jennifer Whipple, “Music Educators’ Perceived Effectiveness of Inclusion,” Journal of Research in Music Education 62, no. 2 (2014), 148-160.

5 Peter J. Chung, et al., “Disorders of Written Expression and Dysgraphia Definition, Diagnosis, and Management,” Translational Pediatrics 9, No. 1 (2020), S46-S54.

6 “What is Discalculia,” Learning Disabilities Association of America, Accessed December 1, 2024, https://ldaamerica.org/what-is-dyscalculia.

7 Prima Vitasari, et al., “The Relationship Between Study Anxiety and Academic Performance Among Engineering Students,” International Conference on Mathematics Education Research 8 (2010), 490-497.

8 Shannon McDonald, “Inclusivity in the Private Studio: Teaching Students with Learning Disabilities, NACWPI Journal 70, no. 3 (Spring 2023), 4-7.

9 Mary Adamek and Alice Ann Darrow, Music in Special Education (Silver Spring: American Music Therapy Association, Inc., 2018).

10 “What is Specific Learning Disorder?” American Psychiatric Association, last modified March 2024, www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/specific-learning-disorder/what-is-specific-learning-disorder.

11 “SiHyun Uhm,” SiHyun Uhm, last modified July 14, 2022, https://sihyunuhm.com.

Photo by Shannon McDonald

Dr. Shannon McDonald (she/her) serves as adjunct professor of music at Texas Woman’s University, where she teaches classes in musicology, music theory, and clarinet lessons. She is an avid researcher and writer and is currently the editor of the NACWPI Journal.

Photo by SG Photo Studio

Dr. Cecilia Kang (she/her) is the associate professor of clarinet at Louisiana State University, and she is an internationally active Vandoren and Buffet Crampon artist clinician. She obtained her degrees from the University of Michigan, the University of Southern California, and the University of Toronto. Learn more at kangcecilia.com.

Comments are closed.