Originally published in The Clarinet 50/2 (March 2023).

Printed copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

Reprints from Early Years of The Clarinet: Repertoire

This issue’s special reprint section explores facets of the clarinet repertoire, beginning with Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr and Jean Raines’s influential 1981 article on clarinet music by women composers. Next are new music and extended techniques with articles by Kostohryz, Ludewig-Verdehr, Smeyers, and Errante. Along with these perspectives of the past are reflections from some of the original authors, and commentary from a variety of clarinetists around the world on how our repertoire has evolved in the past 50 years.

coordinated by Rachel Yoder and Caitlin Beare

Music for Clarinet by Women Composers — Part I

This listing of works by women composers was originally published in The Clarinet 8 no. 2 (Winter 1981), at a time when inclusion of works by women on concert programs was a rarity. However, Ludewig-Verdehr and Raines found an impressive number of works for this two-part feature, ranging from unaccompanied clarinet to large ensemble works using clarinet. Only solo clarinet works and concertos appear here; read the complete articles at The Clarinet Online (clarinet.org/tco).

by Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr and Jean Raines

Please click here for the full list of music by women composers compiled by Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr and Jean Raines

FOREWORD

Throughout history, little notice has been taken of women as composers. No opinion shall be put forward here why this has been and apparently continues to be so. But quite contrary to Schopenhauer’s claim that women are “nonintellectual beings,” many women are known who because of their creative gifts certainly deserve the attention that is unconditionally accorded any composer. Creative achievements must be judged by their artistic level irrespective of the author’s sex.1

Until recently, music by women composers was seldom heard in concert halls; however, this situation has changed rapidly in the past few years. Now women composers are coming into their own, and as a result of their own efforts and those of various organizations, are receiving an increasing number of performances of their works. The purpose of this compilation is two-fold: first, to bring attention to the many available works written for clarinet by women composers; second, to encourage these and other women composers to write more music for the clarinet.2

The sources for this listing are many. Over 450 music publishers in the United States, Europe (including eastern European countries), the Soviet Union, New Zealand, Australia and Asia were contacted. Notices were placed in many trade journals and newsletters. The response was excellent and enthusiastic, and many women, particularly in the United States, England and Scotland, wrote directly and sent listings of their works. In addition, standard guides for clarinet repertoire, new music listings, magazines, catalogs and major headings of clarinet music in the catalogs of the Library of Congress were consulted. Of particular assistance was Karen McNerney Famara, librarian of the American Music Center, whose knowledge of contemporary American music and interest in this project were invaluable.

In the course of this project, books, recordings, publishers and organizations devoted to women composers were uncovered and these have been listed following the “Addresses and Bibliography” section. The list is, by no means, to be considered complete, but it does illustrate the growing interest in this rapidly developing area. Several of the sources listed in the bibliography contain further and quite extensive information about published and unpublished books and articles in the area of women’s music. One also finds that courses about women in music are increasingly being offered in colleges and universities, and that seminars, festivals and concerts of women’s music are frequently presented. Further, the College Music Society has a very active committee on the Status of Women, guided by Adrienne Fried Bloch of the Graduate School at the City University of New York. At their annual meetings, the Society presents sessions on various aspects of women in music. In 1976, the Society published The Status of Women in College: Preliminary Studies edited by Carol Neuls-Bates, which includes a number of articles by different contributors on women’s activities in college and university situations. A second report, The Status of Women in College Music, 1976-77: A Statistical Study by Barbara Renton is also available from the Society. And finally, Patelson’s Music House, one of the important music stores in New York, has set aside a section devoted to music by women composers. This interest and support are encouraging; however, judging from the following responses of two publishers in Germany and Sweden, there is still room for considerable progress in the attitude toward women composers:

1 The German publisher: You asked if we’ve published any music for clarinet by women composers. I’m sorry but I’ve to deny it. In Germany most of the music published is composed by men. But I don’t think the reason is to find on the side of the publisher.

2 The Swedish publisher: We are sure that you are fully aware of the fact that the kind of material and social premises you are looking for exist in a very limited quantity.

Any attempt to be complete in such a listing is impossible for various reasons, the most obvious being that new compositions are composed and published every day. Also, it is possible that, inadvertently, a composition by a male composer may have slipped into this catalog! Therefore, it is intended that a supplement and revision will be published at a later date.

SOLO CLARINET

Anderson, Olive. Sport Street. 1968. J. Albert and Son.

Beat, Janet. Seascape with Clouds. 9’. 1978. The Scottish Music Archive.

Beyer, Johanna Magdalena. Suites I and II. 1932. American Music Center.

Colaco Osorio-Swaab, Reine. Sonatine. 1946. Donemus.

Desportes. Yvonne. La Naissance d’un papillon. 1977. Gerard Billaudot.

Diamond, Arline. Composition for Solo Clarinet. 6’ 15”. 1963. Tritone Press.

Dvorkin, Judith. Monologue in Three Movements. 1963. American Music Center.

Erickson, Elaine. Trifles. 1969. Library of Congress.

Fishman, C. Marian. Glimpses. 1969. American Music Center.

Frasier, Jane. Three Short Sketches. 1973. Composer.

Gipps, Ruth. Prelude for B-flat Clarinet (or Bass Clarinet), Op. 51. 1977. Library of Congress.

Griebling, Margaret. Enigma. Composer.

Gyring, Elizabeth. Scherzando. 1963. Henri Elkan.

Henderson, Moya. Glassbury Documents No. 1. 1978. Australia Music Center.

Hoover, Katherine. Set far Clarinet. 5’. 1978. American Music Center.

Ivey, Jean Eichelberger. Sonatina for Unaccompanied Clarinet. 10’. 1963. Carl Fischer.

Jeppsson, Kerstin. 4 Pezzi for klarinett solo. 1973. STIM’s Informationscentral.

Lutyens, Elisabeth. Tre, Op. 94. 8-9’. 1973. Olivan Press.

Mackie, Shirley. Three Movements. 1969. Library of Congress.

Mamlok, Ursula. Polyphony I. 1968. Composers Facsimile Edition.

Marbe, Myriam. Incantatio: Sonata for Clarinet Solo. Hans Gerig.

Miller, Elma. Kalur. 1976. Composer.

Pentland, Barbara. Phases. 10’. 1977. Canadian Music Center.

Ran, Shulamit. For an Actor–Monologue for Clarinet. 9’. 1978. Theodore Presser.

Shaffer, Cynthia Tucker. Aristeia for Clarinet Alone. 4’. 1976. Composer.

Snow, Mary. Monodies. Lariken Press.

Strutt. Dorothy. Five Grotesque Dances for Clarinet in A. 1961. Composer.

_____. November Rose. 1976. Composer.

_____. Three Pieces for Clarinet in B-flat. 1973. Composer.

_____. Variations for B-flat Clarinet. 1961. Composer.

Swain, Freda. Three Whimsies. Bourne.

Tailleferre, Germaine. Sonata. 4’30’. 1957. Rongwen.

Tucker, Tui St. George. Overture for Solo Clarinet. Harold Branch.

Weigl, Vally. Loiseau de la vie. 10’. American Composers Alliance.

Welander. Svea. Preludium for solo klarinett. 3’. 1962. STIM’s Informationscentral.

Wheeler. Gayneyl Eby. Suite. Composer.

CONCERTOS, CONCERTINOS AND SOLOS WITH ORCHESTRA OR BAND

Archer. Violet. Concerto for A Clarinet. 1968. Canadian Music Center.

_____. Concertino for Clarinet in A and Orchestra. 15’. 1946. rev. 1956. Berandol.

_____. Fantasy for Clarinet and Strings. 1968. Canadian Music Center.

Bailey, Judith. Concertino for Clarinet and Orchestra. 1977. Composer.

Eckhardt-Gramatté, S.C. Triple Concerto. Cl. Bn, Tp with Orch. Associated Music Publishers.

Fontyn, Jacqueline. Colloque. Fl, Ob. Cl, Bn. Hn with Str Orch. 13’. 1970. Seesaw.

Fromm-Michaels, Ilse. Musica Larga. Cl with Str Orch. Hans Sikorski.

Gotkovsky, Ida. Concerto for Clarinet and Orchestra. (Pno reduction available). Theodore Presser.

_____. Concerto Lyrique. Cl with Str Orch. Gerard Billaudot.

Gyring, Elizabeth. Divertimento. Fl, Cl, Hn with Str Orch. American Composers Alliance.

Lutyens, Elisabeth. Chamber Concerto No. 2, Op. 8. Cl, T Sx, Pno Concertante with Str Orch. 10’. 1940-41. J. & W. Chester.

Maconchy, Elizabeth. Concertino for Clarinet and String Orchestra. Ms. Listed in Thurston. Other works published by Oxford University Press.

Mariotte, Antoine. En Montagne. Ob, Cl, Bn with Str Orch. Maurice Baron.

Musgrave, Thea. Concerto. 22’. 1968. J. & W. Chester.

Philiba, Nicole. Concerto Da Camera. (Pno reduction available). Gerard Billaudot.

Roger, Denise. Concertino pour clarinette et orchestre a cordes. (Pno reduction available). Editions Francaises.

Rueff, Jeanine. Concertino, Op. 15. (Pno reduction available). 1950. Alphonse Leduc.

Seleski, Liz. Interlude Romantique. Cl with Band. 4’18”. 1972. Kendor.

Sherman, Elna. Concertante for Clarinet and Orchestra. American Composers Alliance.

Swisher, Gloria Wilson. Concerto for Clarinet and Orchestra. Composer.

Szajna-Lewandowska, Jadwiga. Capriccio for Clarinet and Strings. 15’. 1960. Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne.

Vorlova, Slava. Concerto. To be published by Czech Music Fund.

Wylie, Ruth Shaw. Concertino. 1967. Library of Congress.

Zieritz, Grete von. Concerto for Flute, Clarinet, Bassoon and Large Orchestra. No publisher listed. Information from Music Clubs Magazine, Vol. 56, No. 1, (Autumn, 1976), p. 18. Other works published by Ries and Erler.

Endnotes

1 Foreword to a catalog of women’s music from Elizabeth Thomi-Berg Publishers in Munich, West Germany.

2 The primary focus of this project is music written for the B-flat and A clarinets, although some of the works listed use other clarinets as well.

A Practical Approach to New and Avant-Garde Clarinet Music and Techniques

Then professor of clarinet at Michigan State University, Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr gave a lecture on extended techniques at the 1979 International Clarinet Clinic in Denver, Colorado, resulting in this article for The Clarinet 7 no. 2 (Winter 1980), and it has been frequently referenced by performers ever since. It appears here in an abridged form; see the original article for the full bibliography of sources referenced.

by Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr

In the past fifteen years or so, much music has been written for the clarinet using new techniques and compositional devices. In order to be a well-rounded and complete player today, a serious clarinetist must explore these new techniques and music, and the younger one is, the more necessary it becomes to investigate this area of music. We must assume that music will continue to explore new paths and new techniques in the years ahead and will continually challenge us all as instrumentalists. Further, just as we owe it to ourselves to study the new music and techniques, we also owe it to today’s composers to play their works and to encourage them in their composition. As performers need to perform in concert halls as well as practice in practice rooms, composers similarly must hear live performances of their works in addition to hearing them through their inner ear. Because of the bewildering amount of new music and the large number of new techniques, it is hard to know where to begin and what to do. I hope to make some suggestions which may be helpful in approaching this music and learning the new techniques. Thus, this discussion is for those who have yet to try the new techniques, those in the beginning or intermediate stages of this area, and those who wish an organized approach to new clarinet music techniques for teaching purposes.

Let me reiterate that I feel as clarinetists and as teachers or future teachers we all must investigate this ever-growing and increasingly important area of our literature and try to have an organized approach to it. In some ways it is like jumping into a cold lake and finding that once you’re in, the water’s fine! In fact, I think you will find it better than that. I have found that learning new techniques and puzzling out new works is stimulating, interesting, challenging and fun. A whole new and free means of expression becomes available to you and this in itself can be quite exciting.

One of the biggest problems you first encounter in this area is that each piece often is an entity of its own with its own special language, techniques and symbols. This necessitates a careful and often slow study, and at times it seems you must figure out every detail on the page. Sometimes, in fact, learning a new or avant-garde piece is like working a difficult jigsaw puzzle that must be put together very slowly, piece by piece. But just as a completed puzzle is a satisfaction to contemplate once you have finished it, so is a new work, once you have figured out the new techniques and symbols. Furthermore, after playing a few such works, the symbols and techniques begin to reappear and become easier and more familiar just as have the more conventional techniques and symbols learned long ago; then the hardest part is over and you are on your way.

So, where and how to start? First of all, you must know what the new techniques and symbols are and then learn how to produce them. I recommend reading the following five sources initially:

1 Paul Zonn’s article, “Some Sound Ideas for Clarinet.” As he himself writes, the article “is a brief description of some of the possibilities of the clarinet as a new timbral resources” and is designed to “whet the reader’s appetite so he or she will go forth and experiment as composer or clarinetist, one with the other, to discover a sonic realization.”

2 Gerard Errante’s four articles, “Contemporary Aspects of Clarinet Performance.” These articles catalog the many new effects and techniques of the clarinet, telling which pieces use what, and include a discography. This is an outstanding and informative source.

3 Phillip Rehfeldt’s book, New Directions for Clarinet. This excellent source gives a general background and overview of the whole field (including electronics) plus many details and specifics and provides an outstanding bibliography as well. For the serious clarinetist, this book is a must.

4 Ronald Caravan’s dissertation, Extensions of Technique for Clarinet and Saxophone. This outstanding work includes a most thorough and perhaps the best discussion of multiphonics and their acoustical properties with suggestions on how to produce them. Also included is a list of multiphonic fingerings, various exercises and études using multiphonics, as well as charts of quarter-tone fingerings and timbre-variation (or color-variation) fingerings. Finally, there is a chapter on other extensions of technique: vibrato, glissando, articulation variations, percussive effects, air sounds, vocal sounds and the like.

5 Frank Dolak’s dissertation. Augmenting Clarinet Technique: A Selective, Sequential Approach through Prerequisite Studies and Contemporary Etudes. This informative and practical work contains a discussion (including performance suggestions) of lip bends, harmonics, harmonic arpeggios and scales, multiphonics, microtones, dyads (double stops), quarter tones, the altissimo register and the like with some excellent studies and etudes using these techniques.

Now, what are some of the new techniques and which of these are often stumbling blocks? Some techniques such as flutter-tonguing, glissando and vibrato are already in the playing vocabulary of most clarinetists and if not, they should soon become a part of the player’s technique. … Other techniques such as quarter tones, microtones (which may also be thought of as timbre- or color-variation tones), as well as key (or timbre or color) trills are not particularly difficult; often you can figure these out by yourself with a little experimentation or you can refer to the Rehfeldt book or Caravan dissertation. These techniques generally do not present any real obstacles. However, I have found that there are three major stumbling blocks in learning the new and avant-garde music which do cause some difficulty:

1 Playing (fingered) double stops or multiphonics

2 Producing multiphonics by playing and singing or humming at the same time

3 Reading or deciphering new symbols and notation

PLAYING (FINGERED) DOUBLE STOPS OR MULTIPHONICS:

Before discussing how to produce and practice multiphonics, let me give you a little background in this area by quoting from articles by some of the experts in the field of avant-garde clarinet music and techniques:

Gerard Errante, “Clarinet Multiphonics”: “There is an unwarranted fear of the difficulty of this technique.”

Lawrence Singer, “Multiphonic Possibilities of the Clarinet”: “All clarinet fingerings can produce multiphonic sonorities.” “The clarinet is the only member of the woodwind family that can emit multiphonics with any given fingering—traditional or otherwise.”

Paul Zonn, “Some Sound Ideas for the Clarinet”: “The computer has printed for me over a half million (multiphonic) fingering combinations possible on the clarinet. I have produced double stops or multiphonics on 97% of these in a random sampling.” This gives you an idea of the number of multiphonics possible and available to us.

Gerard Errante, “Clarinet Multiphonics”: “Virtually no adaption of the tone generating mechanism, i.e., reed, mouthpiece and ligature, is required in order to produce multiphonics successfully. All that is necessary is some flexibility of embouchure and oral cavity, an open mind and a little patience.”

Gerald Farmer agrees in his “Comprehensive View of Multiphonics”: “Experimentation with various equipment has led this author to conclude that the same mouthpiece, reed, ligature and instrument used for traditional performance techniques may be used to perform multiphonics,” with which Phillip Rehfeldt also agrees. (It is interesting to note that in these articles the authors invariably agree, and they are considered to be the recognized experts in this area.)

Farmer goes on: “A softer or lighter reed . . . may allow for greater flexibility, especially at softer dynamic levels. A well-balanced reed seems as important in producing multiphonics as it does for traditional techniques. Experiments with moving the reed to the left or right of center on the mouthpiece may be helpful for eliminating resistance.”

As to actually producing the multiphonics:

Gerard Errante, “Clarinet Multiphonics”: “I suggest you experiment by using more mouthpiece, a less firm “pucker” type embouchure, and a more open oral cavity. In most cases all that will be required is a little experimentation and a low frustration level.”

Gerald Farmer, “Clarinet Multiphonics”: “Experiment with different amounts of air pressure, lip pressure and embouchure manipulation.” “General relaxation of the embouchure and oral cavity, along with slightly less lip pressure, often allows greater sensitivity to reed vibration. Air pressure may be described as less forced, with a feeling of slow, steady flow of air …”

In “A Comprehensive View of Multiphonics,” Farmer says “as mastery of multiphonic tone production improves, less deviation from a normal embouchure will be required.”

A few other quotes about problems one might encounter:

Lawrence Singer, “Multiphonic Possibilities of the Clarinet”: “When the multiphonic begins to ‘crack’ or lose stability it has been played either too loudly or too softly.” A player “may find it difficult to play a multiphonic simply because he is not bringing into play with the fingerings the correct amount of air pressure and lip pressure.”

Ronald Caravan, “Introducing Multiple Sonorities”: “The production of most multiple sounds requires a more delicate balance of tongue position and embouchure factors than do most conventional single tones.”

A few final quotes:

Phillip Rehfeldt, “Some Recent Thoughts”: “The ability to play multiphonics accurately, however, is not necessarily to be expected with already established performance habits. The technique usually needs to be developed in the same way” (we learn other techniques on the clarinet).

Lawrence Singer agrees in “Multiphonic Possibilities”: “New techniques and new ideas generally demand a certain amount of time and effort on the part of the player. The multiphonic techniques have some difficulties to be mastered too, but certainly nothing that could be labeled excessively difficult for the advanced reed player.”

These statements are taken from a number of articles which would be invaluable to anyone interested in learning to play or improve his playing of multiphonics on the clarinet. I have quoted at length from these articles because I want to show the wealth and variety of information contained in them and hope this will interest you enough to seek out these articles and read or re-read them.

Now to the actual playing of multiphonics — some work easily, some work poorly, some can be played loudly, some can be played only at a soft dynamic level. Like any other technique on the clarinet, they need to be learned and practiced in an organized fashion. In producing multiphonics there are a number of small but important changes from the usual ways of playing. These involve changes of jaw, air and lip pressure, variable tightness of embouchure, different throat openings, and flexible tongue position. If you experience difficulties in playing multiphonics you might try the following:

1 Take more mouthpiece into the mouth.

2 Use a less firm or looser embouchure.

3 Have a more open or relaxed oral cavity which involves flexibility of tongue position. (Generally this involves having the tongue lower in the back of your mouth, but the opposite also works well for some multiphonics so one must experiment.)

4 Make a change in the velocity and direction of the air stream. Think of a less fast-moving air stream, that is, a slower but still steadily flowing air stream. Also think of pointing or directing the air more downward for some multiphonics, more straight ahead for others. Again one must experiment.

5 Use a somewhat lighter, less stiff reed. In some cases this makes for more freedom of response, but too light or soft a reed can be a hindrance also.

6 Use a more open mouthpiece or try using less embouchure pressure on a close mouthpiece to simulate a more open mouthpiece.

7 Employ more or less jaw and lip pressure. For example, pull the jaw back away from the reed; or push the jaw more firmly into the reed, and perhaps move the lower lip slightly farther down on the reed while doing this. (One way to increase the jaw pressure is to pull the clarinet closer to you.)

Ways of helping a multiphonic speak better and more reliably vary with each multiphonic as well as with different people and their equipment, so it is necessary to experiment with the seven variables I have just enumerated.

As to exercises for practicing multiphonics, I suggest the following approach:

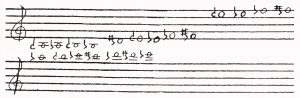

Practice the Preliminary Multiphonic Exercises [see Examples 1–6]. These generally speak easily and give one a sense of the feel and sound of multiphonics.

Examples 1-5

Example 6

PRODUCING MULTIPHONICS BY PLAYING AND SINGING OR HUMMING AT THE SAME TIME:

A second new technique and a kind of multiphonic which might prove to be a stumbling block in learning new or avant-garde music is playing and humming or singing at the same time. Below are a number of preliminary exercises for playing and singing simultaneously [see example]

READING OR DECIPHERING NEW SYMBOLS AND NOTATION:

A third possible stumbling block in learning new and avant-garde music can be reading and deciphering the notation and symbols of a work. Often it is difficult to know what the symbols indicate since exact notation and symbols are still to be codified and not all composers give explanations for the symbols they use. The Dolak dissertation provides useful information on this subject. There are two excellent articles and two books as well which may be helpful:

Articles:

1 Kurt Stone, “New Notation for New Music” is a history of notation and what has and is being done to make the practice more uniform. It also contains a listing of symbols for new vocal and instrumental techniques.

2 Nicholas Valenziano, “Contemporary Notational Symbols and Performance Techniques for the Clarinet” shows symbols which indicate air sounds, articulation, changes of tone color, key clicks, vibrato, multiple sounds, etc. and contains a discussion of various works using these. It is particularly useful as it deals specifically with works for clarinet.

Books:

1 Howard Risatti, New Music Vocabulary is a dictionary of notational use of the past few decades taken from 600 scores and includes 7 pages of notational symbols for woodwinds. It is an excellent book and quite helpful.

2 Erhard Karkoschka, Notation in New Music surveys the most important present-day notation divided by instruments and provides an analysis of several types of new notation, as well as experimental types of notation, and a new vocabulary capable of expressing contemporary ideas. It is quite detailed and advanced, largely useful for composers or the most advanced contemporary players.

SOLO MATERIALS:

When one begins playing avant-garde compositions, I find it is good to play unaccompanied works first, since it is easier not to have to rely on others having an equal interest and aptitude for learning new music and techniques. The amount of new music available for various instrumentations using clarinet is simply staggering and it is hard to choose which works to play. I recommend the following order in playing the unaccompanied works which are listed in the bibliography. The list is subjective and entirely my own opinion, but I feel it would be useful to study the works in this order:

(1) Onofrey, Labryinth

(2) Laporte, Sequenza

(3) Smith, Fancies

(4) Beall, Study (listed under studies)

(5) Caravan, Duets

(6) Bettinelli, Studio da Concerto

(7) Benjamin, Articulations

(8) Caravan, Excursions

(9) Obradovic, Mikro-Sonata

(10) Stalvey, PLC-Extract

(11) Bucchi, Concerto

(12) Bassett, Soliloquies

(13) Smith, Variants

(14) Eaton, Concert Music

(15) Tisné, Manhattan Sony

(16) Laporte, Reflections

(17) Desportes, La naissance d’un papillon

(18) Goehr, Paraphrase

(19) Ran, Monologue

(20) Antoniou, 3 Likes

(21) Testi, Jubilus 1

(22) Zonn, Revolutions

(23) Lehmann, Mosaik

(24) Boulez, Domaines

(25) Davies, The Seven Brightnesses

Let me make a few final observations. When you are learning a new piece and run into difficulty, you might refer to the sources listed in the bibliography, or listen to a recording of the work (I found this most helpful in deciphering the notation and symbols of a few works when I first began to play them), or ask a composer, or seek out another clarinetist who is knowledgeable in this area. For example, you might invite an Errante, Rehfeldt, Zonn or Farmer—someone near your area—to come to your school or college for a lecture-demonstration-discussion.

[See the original 1980 article in The Clarinet 7 no. 2 for Verdehr’s extensive bibliography of resources for performing new techniques, as well as the full listing of works for solo clarinet as well as clarinet and tape. Ed.]

The Open-Minded Clarinetist

American-born clarinetist David Smeyers, who has lived in Europe since 1977 and was professor of new music at the Cologne Musikhochschule from 2003 to 2022, wrote this first installment of “The Open-Minded Clarinetist” in The Clarinet 14 no. 2 (Winter 1987). This influential column continued until 1998. Smeyers is still performing after over 40 years with Beate Zelinsky as Das Klarinettenduo Zelinsky/Smeyers.

by David Smeyers

“There would not exist the style of Louis XIV if he had liked to live in the style of Louis XIII. And thus Louis XV and his successors were conscious of their own time and abhorred living in a second-hand style.”

– Arnold Schoenberg1

Let me begin by explaining how it came to pass that James Gillespie asked me to write on avant-garde clarinet music for The Clarinet.

For over 14 years I have studied, practiced, performed, listened to, recorded, admired and criticized new, avant-garde and contemporary music. Not because I was forced to or because it seemed like the financially intelligent thing to do; no, because I enjoyed this music. I enjoyed the sounds, the challenge and the experience of new music.

After receiving The Clarinet for over seven years, I had noticed a reduction in the number and size of the articles concerning the topic of avant-garde music. I was saddened by these facts, but I was really angry after receiving my issue of The Clarinet last spring. It was in that issue on page 6 (“From the Editor’s Desk”) that I read, “Many felt that jazz and avant-garde should be covered less [in The Clarinet], but considering how few articles we have on those subjects each year, I’m not certain how we can eliminate those areas altogether.”

My first reaction was to cancel my membership. I have no interest in belonging to an organization that wears blinders. But before leaving the International Clarinet Society I decided to write a letter expressing my disappointment.

Mr. Gillespie’s answer was to ask me to contribute articles on a regular basis concerning avant-garde music in Europe.

I can’t believe that all of the readers of The Clarinet are not interested in the new repertoire that is presently being composed. Imagine where we would be in the clarinet world (not to mention the musical world) without the pioneer work of musicians such as Anton Stadler, Heinrich Baermann, Johann Simon Hermstedt and Richard Mühlfeld. Of course I have mentioned only the most obvious and illustrious of our “forefathers.” Today’s most famous example is probably the late Benny Goodman. Although best known as a jazz clarinetist, he commissioned new works from Bartók, Copland, Hindemith and Milhaud, to name a few. These works are a vital part of our repertoire today.

Never before have audiences and musicians spent so much time and energy living in the past, to the extent of ignoring the present, not to mention the future. It is necessary to learn and perform the standard everyday pieces, but I consider it parasitic to take only what is available and not to replace or add.

Are most of you content just to perform works written during the 18th and 19th centuries? Is it too much work to learn pieces that you didn’t study with your teacher at the college, university or conservatory level? Why aren’t more musicians curious about what their composing contemporaries are doing and creating? In the sciences it would be considered a sin not to attempt to expand knowledge and further horizons. I hope that you are aware of the very large number of extremely fine musical compositions written by the Second Viennese School (Schoenberg, Webern and Berg) and their colleagues. For my articles on new music I will have to assume that you are acquainted with the “normal” repertoire written before World War II. I will concentrate on the generations that have followed.

I have lived and worked in West Germany and Europe for almost 10 years now, and, because the musical life here differs quite substantially from that in North America, I will give you some background information concerning the musical scene here.

The 100 professional orchestras of Western Germany are legend by now. What might not be known is the large number of international festivals that take place. Each city, regardless of its size, tries to set itself apart from the others. As a result, festivals for jazz, baroque, classical and modern music are to be encountered everywhere all through the year. In addition to the traditional orchestral and chamber music festival for new music in Donaueschingen, regular performance opportunities have sprung up in most all major cities and even several smaller ones. … Witten, with a population of 107,000 in North-Rhein Westphalia, for example, has sponsored a festival for new chamber music for over 40 years. Other cities have chosen to sponsor composition prizes or competitions.

Is there really so much interest here for this modern music, you may ask? Yes and no; concertgoing here has a very long tradition, and, as a result, classical music has a place in normal, everyday life. Through the sponsorship and support of the radio houses, these forums are helped over any hard times. In fact, the radio houses (of which there are 10) make most of the new music performances possible. The radio is not controlled by the government and is dedicated to serving majority and minority tastes of the public. This applies even to instances where a profit is not to be made. The Westdeutsche Rundfunk (WDR) here in Cologne broadcasts a sizable number of hours of new music each week. Only a small portion of the works broadcast are taken from records; the large majority were recorded here at the radio in studio productions or possibly by one of the other radio houses in Western Germany or Europe.

The radio houses promote new music through regular live concerts and by granting a large number of commissions to composers to create new works, in much the same way as the wealthy or royalty did some 200 years ago.

All of this activity has led to an education of the public-at-large. They are cognizant that new works are being produced, and they know the names of the well-known modern (living!) composers and even some of the names of the younger generations. They have built up not only a tolerance, but an understanding of the music of their (your) time, just as one learns to appreciate other art forms.

I am not saying that the new music situation in Europe is ideal and that elsewhere it is catastrophic; I am only too well aware of the work that needs to be done here—the ground, however, is fertile.

But all the interest in the world on the audience’s side will do no good if the performers are ignorant of, or boycott, avant-garde music and stand in the way of progress.

What do I hope to accomplish with these writings? I hope to interest you and make you curious about new and newer music. I hope to provoke you, stimulate you to experience this repertoire first hand. For those of you who have never before performed the music of our time, I hope to prod you into taking your first steps. For those of you who have already made these first steps, I hope to make you eager to move farther afield.

How can you learn more about newer repertoire and how to present it? Listen to every bit of new music possible, live and recorded. Talk to performers and composers after concerts. Collect and study publishers’ catalogues and repertoire lists. Read and keep up with articles, reviews and analyses of new music in the many available journals. In general, be curious and inquisitive. Get to know the musical and cultural languages that you as a modern musician (artist?) must speak. There are many musical languages, and you have to know as many as possible to develop your own musical taste in this field, just as you did in other fields.

For the uninitiated, but eager to learn, clarinetist, I suggest (re)reading Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr’s fine article concerning avant-garde music and techniques found in The Clarinet, Vol. 7, No. 2 (Winter, 1980). In spite of the circumstance that her article is over seven years old, it contains many timely facts and tips and quite a bit of encouragement. Most important is her list of works for solo clarinet and the books and dissertations contained in the bibliography.

At the close of this article I have listed the books, etc. that I consider to be essential to every modern clarinetist’s library. These are the materials that I refer to almost every day; they have proven to be most reliable. Unfortunately, 99% of this literature is in English and only applicable to the normal Boehm System instrument. (Garbarino, for Full Boehm, and Heine’s book were the only worthy exceptions that I have found to date.) The German System player is left to her/his own wits. I hope that this situation changes soon.

For the summer issue of The Clarinet I’ll interview the German (avant-garde) composer Hans-Joachim Hespos and will look at some of his compositions for clarinet(s). Until then “listen naively, sensitively and open-mindedly.”2 …

ENDNOTES

1 Arnold Schoenberg, Style and Idea, ed. Leonard Stein, trans. Leo Black (London and Boston: Faber and Faber, 1975), p. 2376.

2 Ibid., p. 114.

The Open-Minded Clarinetist’s (Absolute Minimal) Modern Library Of How-To Manuals and Repertoire Ideas:

Aber, Thomas and Terje Lerstad. ‘Altissimo register fingerings for the Bass Clarinet,” The Clarinet (Summer, 1982), pp. 39-41.

Drushler, Paul. The Altissimo Register: A Partial Approach, Rochester: Shall-u-mo Pub., 1978.

Farmer, Gerald. Multiphonics and Other Contemporary Clarinet Techniques, Rochester: Shall-u-mo Pub., 1982.

Garbarino, Giuseppe. Metodo per Clarinetto with an English Translation by Reginald Smith Brindle, Milano: Edizioni Suzini Zerboni, 1978.

Heim, Norman. “Music for the Bass Clarinet Parts I—VIII,” The Clarinet, series starts with the Spring, 1979 issue, pp. 18-21.

Heine, Alois. Akustische Phänomene (Acoustical Phenomena), Munich and Salzburg: Musikverlag Emil Katzbichler, 1978.

Ludewig-Verdehr, Elsa. “A Practical Approach to New and Avant-Garde Clarinet Music and Techniques,” The Clarinet (Winter, 1980), pp. 10-15 & 38-41.

Rehfeldt, Phillip. New Directions for Clarinet, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977.

Quarter-Tone Clarinet

Milan Kostohryz was a professor of the School of Music in Prague, Czechoslovakia, and published this article in The Clarinet 3 no. 3 (May 1976).

by Milan Kostohryz

The process of technical improvement of the clarinet reached its climax at the moment when its complete chromatization was achieved by Klose and Buffet, c. 1843, and Müller and Heckel in 1845. This circumstance rendered it possible for the clarinet player to play with assurance in any scale and solve any problems of fingering he meets within his practice. Thus it was possible to remove technical reasons for use of two other clarinets, those in A and C. This is the reason why some players transpose parts written for A clarinet and almost all of them transpose parts written for C clarinet. The only exceptions form parts where the author expressly requires the use of C clarinet with regard to the quality of its timbre (as for example Richard Strauss in Arabella).

Yet not even the perfect chromatization meant the ultimate end in the development of the clarinet. There are many contemporary composers who, in order to express their thoughts and emotions, strive to enrich the basic musical tone substrata by still smaller parts of intervals than the usual semitones. They even elaborated a new compositional technique in quarter-tones, i.e., intervals formed by subdividing the usual semitones into two quarter-tones. To produce quarter-tone intervals even the semitone clarinet may be used on which a certain number of quarter-tones may be produced by means of a simple combination of touches. Requirements to use quarter-tones sporadically are met with in many modern composers (among the Czech ones, I should like to mention especially Zb. Vostřák, M. Kopelent, and V. Srámek; among the Polish ones Wl. Kotónski, Lutoslawski, and Penderecki; among the Italian ones L. Nono, Berio, and Manzoni; and among the Spanish Louis de Pablo).

The notation of quarter-tones in the musicography was introduced by the Czech composer Alois Hába: the mark serves to denote the sharpening of a tone by one quarter-tone and the mark denotes the sharpening of the basic tone by three quarter-tones, while the mark denotes flattening the basic tone by one quarter-tone.

The semitone clarinet of French system is able to produce the following quarter-tones [see Ex. 1].

Some of these are from the viewpoint of intonation exactly pure. Many, however, must be tuned up by means of correct impression of the lips, and some again differ by their timbre or dynamics (being damped).

This incomplete series of quarter-tones, however, cannot satisfy an author composing his works in the quarter-tone system. He needs necessarily all the tones of the bi-chromatic scale. That was also the reason why the pioneer of the quarter-tone music, the Czech composer Alois Hába, in addition to a quarter-tone piano, harmonium, trumpet and guitar, had had even a quarter-tone clarinet constructed for himself. The instruments were designed and constructed by the firm V. Kohlert’s Sons in Kraslice in North Bohemia. In all, two quarter-tone clarinets were constructed for Hába, the first one, based on the German system, in 1924, and the second one, based on the French system, in 1931. In principle, the question was how to divide the distance between separate holes of the semitone clarinet by further holes answering to quarter-tone intervals and, of course, to solve the problem of fingering the valves in such a way that the clarinet player may operate them easily by ten fingers of his both hands. In contrast to the semitone clarinet, where nine fingers only are engaged, the quarter-tone clarinet requires the use of the right hand thumb, too. In the French system quarter-tone clarinet, the right thumb operates two valves, whereas in the German system, one valve only is needed.

In principle, Kohlert retained the original semitone clarinet adding further valves to enable the player to produce all the tones of the bi-chromatic scale. The designers succeeded in creating an instrument of relatively pure intonation quality. However, the problem of executability of the passage itself remains open when some, and by the way frequent enough, intervals are to be connected. Especially in legato passages a smooth exchange of some more complicated touches is extremely difficult if not sometimes impossible.

Thus, one is entitled to say that we are facing a repetition of the same situation that many years ago was the reason why wooden instruments, then at the beginning of their development, were induced in the Baroque music to play especially in detaché and staccato. The difficult exchange of complicated touches was then executed in gaps (little rests, etc.) between separate tonguings. The future will show to what extent the quarter-tone music will become vital. Only then practice and requirements of composers enforce further development and refinement of the mechanics of quarter-tone clarinets.

A List of Compositions of Czech Authors for the Quarter-Tone Clarinet

Alois Hába, Opus 22, Phantasy for the Quarter-Tone B Clarinet and Quarter-Tone Piano

Alois Hába, Opus 55, Suite for the Quarter-Tone Clarinet alone

Jirí Pauer, Concertino for the Quarter Tone Clarinet and Stringed Orchestra

Karel Stepka, Windowlet for Four Female Voices and the Quarter-Tone Clarinet

Karel Reiner, Duos for Two Quarter-Tone Clarinets

Jirí Kratochvíl, Suite in B major for the Quarter-Tone Clarinet and Semitone Piano

Miroslav Pone, Music for the Quarter-Tone Clarinet and the Quarter-Tone Guitar

Rudolf Kubín, Phantasy for the Clarinet and Piano

THE ELECTRONIC CLARINET

Since the publication of the article excerpted here, originally published in The Clarinet 17 no. 3 (May/June 1990), the technology has evolved, but F. Gerard Errante’s pioneering perspective on performance practice with electronics remains relevant.

by F. Gerard Errante

For the adventuresome clarinetist seeking to expand his or her repertoire in this area, the logical first step is to choose a work with prerecorded electronic tape. All that is required is a tape recorder and a sound system. The method of coordinating with the tape varies from piece to piece, but usually a score is provided with both clarinet and tape part notated. Depending on the nature of the composition, the tape part may employ conventional pitch notation or graphic notation. Also a time line may be employed, in which case a stopwatch will be required. Often the use of a stopwatch is most helpful, especially in the early stages of learning a work. Ultimately, however, the tape portion will become more familiar and it is important to rely upon the ear for cues. It is common for tape decks to move at slightly varied speeds, and so the timing, especially of a lengthy work, may be off significantly.

Several accessible works which will serve as an introduction to this medium include Antiphon II by Michael Horvit, Going Home by Edward Miller and Soundets by Scott Wyatt. These compositions are clearly notated and require no extended techniques. For those seeking to explore some early works in this medium which began in the 1960s, Study by Charles Whittenberg and Piece for Clarinet and Tape by Edward Miller are of interest. Another important work from the Sixties is Animus III by Jacob Druckman.

Ideally one of the purposes of the electronic medium is to create sounds which are unique rather than merely imitating conventional instruments. One of the advantages, then, of performing with prerecorded tape is the expanded possibilities of sonic and rhythmic resources. This undoubtedly will add interest to an otherwise conventional program. Other obvious advantages are: the tape is available at any time, it doesn’t charge a fee for rehearsals or performance, and it doesn’t talk back or disagree with your interpretation. On the other hand it is of course fixed, and so there will be no variety or spontaneity from performance to performance. Reliability, however, is an important attribute and at least some variety can be added in the live clarinet part.

When adjusting for balance with speakers, it is advisable to have a colleague listen from the audience. Occasionally it will be necessary to adjust placement of the speakers so they can be heard clearly by the performer. Another, perhaps more satisfactory solution, is to have a small speaker serving as a monitor facing the performer. Finally, it may be advantageous to amplify the clarinet sound to achieve a better balance with the tape. I have also found it helpful o enhance the clarinet sound with a small amount of delay or reverberation. This tends to avoid the separation of an “acoustic” clarinet with an “electronic” tape, thereby creating a more cohesive whole.

A second, related category are works with self-prepared tape. These pieces will require a recording studio where a tape can be prepared. Most often what is involved is a relatively simple procedure of recording a second clarinet part so in effect you will be performing a “duet” with the tape. Successful works in this category include Phoenix Wind by Joseph Kasinskas and Soundspells 6 by Meyer Kupferman. Some other self-prepared tapes, such as the tape version of Steve Reich’s New York Counterpoint, involve complicated overdubbing and will no doubt require a professional studio to produce a satisfactory result.

In recent years with the increasing sophistication of electronic technology, more and more works are becoming available using live or real-time electronic processing. This simply means that the electronic sounds are produced by the performer as he or she is playing in “real time,” not by a composer putting sounds on tape in a studio. The advantages are added flexibility and dynamism in the performance. It is always more exciting for an audience to witness a performer in action creating electronic effects on the spot. On the other hand, greater complexity can be produced in a studio on prerecorded tape. Naturally there are a number of compositions that utilize prerecorded tape along with real-time processing.

Many clarinetists, having mastered a variety of complex operations necessary for top-level performance, are reluctant to delve into the mysterious world of electronics. While it is true that all those buttons, knobs and cables can be confusing, it can also be quite straightforward as many of the new devices are very simple to use. Just as it is not necessary to know the intricacies under the hood of your automobile in which you drive, it is likewise not necessary to understand the inner workings of a digital delay or synthesizer in order to produce some striking music.

Perhaps the most important development in recent years for instrumentalists is the availability of the pitch to MIDI (musical instrument digital interface) interface. This allows any instrument to activate a synthesizer or any other electronic device — a world hitherto reserved for keyboard players. So now, with the flick of a button or foot switch, it is possible to make your clarinet sound like a string section, a tuba, a female chorus, the seashore, a coyote, or virtually anything!

Another fascinating offshoot of the electronic medium is the development of compositions for clarinet and video. (See “The New Medium of Video Performance” by this author in ClariNetwork, Vol. 5, No. 2.) These intermedia works employing electronics as described above in addition to video will add great interest to a recital. The equipment requirements are usually not a problem as most venues, especially in the academic world, have video cassette decks and a video projection system or video monitors available. In most works written thus far, the video is fixed on prerecorded tape. Recent technology is now making possible interactive video pieces, i.e., video which can be controlled in real-time by the performer. Stay tuned for further developments.

While this article has been dealing with the electronic medium using the clarinet, it is important to mention a related area, that is, the development in recent years of the MIDI Wind Controller. These instruments do not produce sounds themselves — they are designed to provided access for the wind player to the world of MIDI synthesis. While it is true that this can be done with a clarinet through a pitch to MIDI interface, there are certain advantages to the instruments designed specifically for this purpose. In the hands of a skilled player, the agility can be quite astounding.

While I have attempted to dispel reluctance on the part of some clarinetists to delve into the wonderful and mysterious world of electronics, there is no doubt at times it can be a frustrating experience. Clarinetists are no stranger to frustration, however. When was the last time you opened a box of reeds and instantly came upon that perfect concert specimen? The usual advice works here as well, i.e., proceed slowly and logically, take a break if you are about to hang yourself with the nearest extension cord, and don’t be afraid to ask for help. It may be a bit demeaning, but that barely pubescent kid in the local rock band can be a very valuable source of information. Also, I have found the personnel in music stores selling electronic equipment, most of whom are performing musicians themselves, to be quite helpful. And I have found the technical support on much of this equipment to be quite good. With a little inquiry, it will certainly not be difficult to locate an enthusiastic, informed assistant. Best of luck on your explorations.

What follows is an abbreviated list of compositions for clarinet and tape, clarinet and self-prepared tape, clarinet and live electronics, and clarinet and video that are recommended works in this medium. …

CLARINET & TAPE

Jacob Druckman, Animus III (1969), Boosey & Hawkes

Roger Hannay, Pied Piper (1975), Seesaw Music Corp.

Michael Horvit, Antiphon II (1974), Shawnee Press

Edward Miller, Going Home (1985), Piece for Clarinet & Tape (1967), American Composers Alliance

Charles Whittenberg, Study (1961; rev. 1962), American Composers Alliance

Scott Wyatt, Soundets (1987), University of Illinois, Urbana, IL 61801

CLARINET & SELF-PREPARED TAPE

Joseph Kasinskas, Phoenix Wind (1977), 127 Oakdale Road, Cherry Hill, NJ 08034

Meyer Kupferman, Soundspells #6 (1982), General Music Publishing Co.

Steve Reich, New York Counterpoint (1985), Boosey & Hawkes (prerecorded tape also on rental)

CLARINET & LIVE ELECTRONICS

Jonathan Kramer, Renascence (1974), G. Schirmer (prerecorded tape also available)

Thea Musgrave, Narcissus (1987), Novello

William O. Smith, Solo (1980), Ravenna Editions

Morton Subotnick, Passages of the Beast (1978), Theodore Presser Company

CLARINET & VIDEO

Roger Greive & T.J. Hinsdale, Clarinet Chromatron (1987), 2709 Winsted Drive, Toledo, OH 43606

Reynold Weidnaar, Love of Line, of Light and Shadow: The Brooklyn Bridge (1982), Magnetic Music Publishing, 5 Jones Street, New York, NY 10014

William O. Smith, Slow Motion (1987), Ravenna Editions

Comments are closed.