Originally published in The Clarinet 46/2 (March 2019). Printed copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco and his Contribution to the Clarinet Repertoire

by Eric Schultz

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco is a name perhaps not many are likely to know today. Though he humbly considered himself a “ghost-writer,” his output was substantial. Castelnuovo-Tedesco (1895–1968) contributed to hundreds of films for MGM and other studios including Columbia, Universal, Warner Brothers, 20th Century Fox and CBS, but was seldom credited. He fully scored at least 14 films, including And Then There Were None (1945) and The Loves of Carmen (1948). When credited, he often appears listed as a “contributing composer,” making it difficult to know what music is actually his in many films. Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s skills were valued in Hollywood because of his excellent ears. He could compose very quickly and did not need to be at the piano. Despite his lack of recognition, he was one of the most coveted teachers of film and television music composition, with students including Jerry Goldsmith, Henry Mancini, André Previn, Nelson Riddle and John Williams.

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco in Florence, 1932 Credit: Photo courtesy of the Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco Collection at the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Today, Castelnuovo-Tedesco is mostly remembered for his guitar music, although he was also one of the contributing composers for Nathaniel Shilkret’s collaborative project the Genesis Suite, for narrator, orchestra and chorus. Seven composers who had left Europe for the United States – Arnold Schoenberg, Nathaniel Shilkret, Alexandre Tansman, Darius Milhaud, Ernst Toch, Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco and Igor Stravinsky – each wrote one movement. Shilkret was a colleague at MGM studios, and a talented clarinetist, having played in both the New York Philharmonic and Metropolitan Opera Orchestra before moving to Hollywood to focus on composing. Of course, the work is also significant for bringing two conflicting contemporaries, Schoenberg and Stravinsky, together in the context of one piece.

European Antisemitism and Marginalization

Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s family history was shaped by centuries of systemic European anti-Semitism. Following the Spanish Inquisition, the Alhambra Decree of 1492 forced his father’s family line out of Spain because they were Jewish.1 From Spain they moved to Tuscany.

A few hundred years later, Castelnuovo-Tedesco was one of the very few Jewish composers who actively wrote during the fascist Italian regime. In 1938, a sort of unofficial curtailment of music by Jewish composers took effect. Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s music was banned from Italian radio. Live performances of his music were limited; for example, in January of 1938 a performance of his Second Violin Concerto “I profeti” was canceled.2 The work, commissioned by Jascha Heifetz in 1931, has three movements subtitled “Isaiah,” “Jeremiah” and “Elijah,” after the ancient Hebrew prophets, and utilizes traditional Hebrew melodies. The composer called this concerto “the most significant among my works of Jewish inspiration.”3

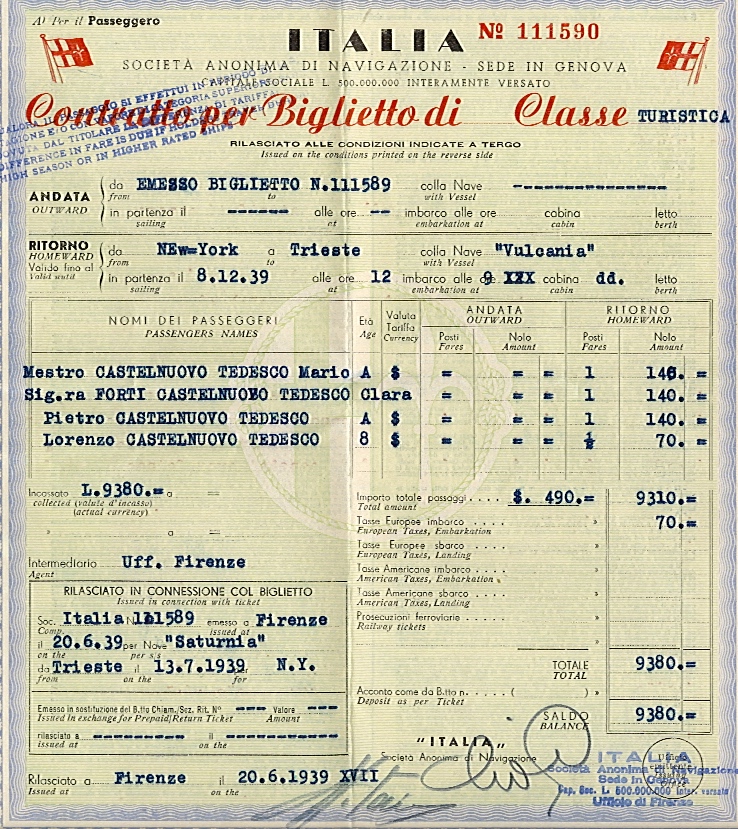

Over the course of 1938, Jewish people in Italy lost their citizenship and jobs, and were prohibited from studying and publishing. Despite his marginalization, it was not until Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s young children were banned from attending school in the fall of 1938 that the Italian racial laws had finally become untenable, convincing him that he needed to leave his home country. He traveled to Switzerland, where he could communicate with his friends Arturo Toscanini, Jascha Heifetz and Albert Spalding without fear of interception by the Italian government. They supported his move. Although it was very difficult for Jewish people at the time to leave Italy legally, it was important to Castelnuovo-Tedesco to do so. Heifetz, by then an American citizen, sponsored his move to the U.S., and provided an affidavit promising him work. With no plans to return, Castelnuovo-Tedesco bought a round-trip ticket and finally left in 1939, right before World War II. After a short time in New York, he left for Beverly Hills.

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s round-trip ticket to the U.S., which allowed him to leave Italy in 1939

Credit: Photo courtesy of the Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco Collection at the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

One year after he arrived in America, he learned of his mother’s passing. She had kept her suffering a secret from him, as she knew he would want to visit her in Italy and that it would be dangerous to come back. On the day that he received the telegram, he also received a phone call from Heifetz offering him a job with MGM studios as a film composer. Castelnuovo-Tedesco accepted, and saw it as the final gift from his mother.

After the war, Castelnuovo-Tedesco received an offer from the Italian government to serve as the director of the conservatory of his choice (Naples or Rome). He was pleased by the offer as a symbol of reconciliation, but ultimately decided to stay in America, and eventually, to become an American citizen.

As a composer, he is difficult to place. Attributed with many labels, including impressionist, neo-classicist, and melodically neo-romantic, he personally disliked categorization. As a student of composition, he wanted to study the music of Debussy, but his first teacher would not allow it. He eventually switched composition teachers and began studies with Ildebrando Pizzetti, a member of the “Generation of 1880” along with Ottorino Respighi, Gian Francesco Malipiero and Alfredo Casella. These composers were among the first Italians in some time whose primary contributions were not in opera. Pizzetti supported Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s study of impressionism and trained him considerably in counterpoint, which proved valuable. A defining feature of Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s work is the brilliant way in which he weaves different melodies together, and the Clarinet Sonata is a great example of this.

Clarinet Works

Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s Clarinet Sonata, Op. 128 was written in 1944-45, but not published until 1977. Because of this delay, it was not often performed because the music was not available. As the work has now been consistently published for more than 40 years, it is time to reconsider this piece for more regular performance. It is a stunning work, especially in its romantic melodies. Outside of this romanticism, however, it is classical in structure and spans four movements, with sonata form used in the first movement and an energetic rondo for the fourth. Interspersed with occasional extended harmonies (perhaps influenced by jazz), and aesthetically impressionistic, glimmering piano passages, the work has a lot to offer, and frankly, should be in the standard repertoire today.

There is no information regarding any kind of commission or dedication for the Sonata, although Castelnuovo-Tedesco must have been aware of the popularity of the clarinet in the United States in the 1940s, due to Benny Goodman’s commissioning of Copland, Milhaud, Hindemith and Bartók. He also had a special respect for the clarinet because of the music of Mozart and Brahms, and as a pianist, had performed Brahms’ clarinet sonatas himself.

Even less known is another chamber piece Castelnuovo-Tedesco wrote for the clarinet, the Pastorale and Rondo for clarinet, violin, cello and piano, Op. 185. Written in 1958, the autograph manuscript exists in special collections at UCLA but is difficult (and expensive) to access. Nicholas del Grazia discussed this in his September 2005 article in The Clarinet.4 Fortunately, Ricordi bought the rights from the Castelnuovo-Tedesco family and finally published the music in 2017. Unfortunately, it is still difficult to find. The music is not currently available through university interlibrary loan

and at this time can only be found at www.musicshopeurope.com (for €39).

The Graudan Ensemble

A dedication to the Graudan Ensemble appears on the manuscript of the Pastorale and Rondo, and previous researchers have been unable to definitively identify the members of this group. It was completely impossible to find information about this group until I ran a search in one particular online newspaper database, www.newspapers.com, which has hundreds of millions of pages of newspapers, completely searchable for text. No other database contained relevant materials. However, this database turned up hundreds of old newspaper articles including recital announcements and reviews for the group, which consisted of world-renowned musicians: cellist Nikolai Graudan; his wife, pianist Joanna Graudan; violinist Eudice Shapiro; and clarinetist Mitchell Lurie. Perhaps these musicians met Castelnuovo-Tedesco in a Hollywood studio while recording for movies. Of course, Lurie recorded for many films, including Mary Poppins, and has an impressive IMDB page including several uncredited movie appearances.

According to newspapers that discuss the program, it seems most concerts performed by the Graudan Ensemble included the Pastorale and Rondo, which featured the group in its entirety, and some reviews indicate that the group would often repeat the energetic Rondo as their encore! One review in the Los Angeles Times from April 2, 1959, notes, “It is attractive, melodious music, scored with orchestral richness that gives each player grateful duties and capitalizes on individual and collective possibilities of varied color. The performance was brilliant and ingratiating.”

Another particularly thorough review in The Press Democrat of Santa Rosa, California, from April 21, 1959, applauds Lurie and congratulates Castelnuovo-Tedesco for fully realizing the capabilities of the ensemble. In fact, I did not find a negative review of the piece or ensemble.

Unfortunately, there is no recording of the piece, and it seems most likely that no one has performed this work since the Graudan Ensemble. Until now, scholarly writing also indicated that this previously unidentified group was probably looking for a companion piece to Messiaen’s Quatuor pour la fin du temps or Hindemith’s Quartet using the same instrumentation. Although no newspaper reviews or announcements seem to support this, it would not be a bad idea for a recital program. Of course, this instrumentation does not have a large repertoire, so we should also encourage our composer friends to consider this configuration when commissioning new works.

Speaking of the future, there seems to finally be a renewed interest in the life and work of Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco. In fact, a film titled The Maestro follows film composer Jerry Herst, who moved to Hollywood to study with the master teacher after World War II. After making film festival rounds to great acclaim, the biopic received its theatrical release in February 2019. Additionally, Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s 853-page autobiography, Una Vita Di Musica, is being translated to English by James Westby, the editor of the original Italian. Since 2015, the Archives of Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco has been working with Edizioni Curci, Milano, to publish the Castelnuovo-Tedesco Collection of previously unpublished works. As for his two clarinet pieces, standard repertoire or not, it is time to advocate for them to be remembered, studied, and at minimum, performed more often. At a time when society is beginning to come to terms with the contributions and plights of its most marginalized citizens, it is appropriate to reconsider the place of Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s works in the clarinet repertoire. v

Bibliography

Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Mario. Una Vita Di Musica. Fiesole: Cadmo, 2005.

Ewen, David. The New Book of Modern Composers. New York: Knopf, 1961.

Grazia, Nicolas Del. “Italian Music for Clarinet 1918-1958: Four Outsiders to La Generazione del’Ottanta.” D.M.A. dissertation, Indiana University, 2003.

Sachs, Harvey. Music in Fascist Italy. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1987.

Saleski, Gdal. Famous Musicians of Jewish Origin. New York: Bloch, 1949.

Westby, James. “Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Mario.” Oxford Music Online, 2001.

Endnotes

1 Gdal Saleski, Famous Musicians of Jewish Origin (New York: Bloch Pub., 1949), 31.

2 Harvey Sachs, Music in Fascist Italy (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1987), 184.

3 Saleski, Famous Musicians of Jewish Origin.

4 Del Grazia, Nicholas. “Rediscovering Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s Pastorale and Rondo, Op. 185.” The Clarinet Vol. 32, No. 4 (2005): 44-47.

* * * * *

Special thank you to Diana Castelnuovo-Tedesco, granddaughter of Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, for facilitating the research process and providing photo permissions.

About the Writer

Eric Schultz currently serves on the music faculty at Iona College, and as a teacher for the Harmony Program in New York City. He is an award-winning clarinetist, including the prestigious Rislov Foundation grant for excellence in classical music, and is the founding clarinetist of the Victory Players contemporary chamber ensemble of the Massachusetts International Festival of the Arts. Eric completed his Doctor of Musical Arts degree in clarinet performance at Stony Brook University. His principal teachers include Alan Kay, Alexander Fiterstein and Melissa Koprowski.

Comments are closed.