Originally published in The Clarinet 45/3 (June 2018). Printed copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

Rock ’n’ Roll Clarinets?!

The Beatles’ Use of Clarinets on

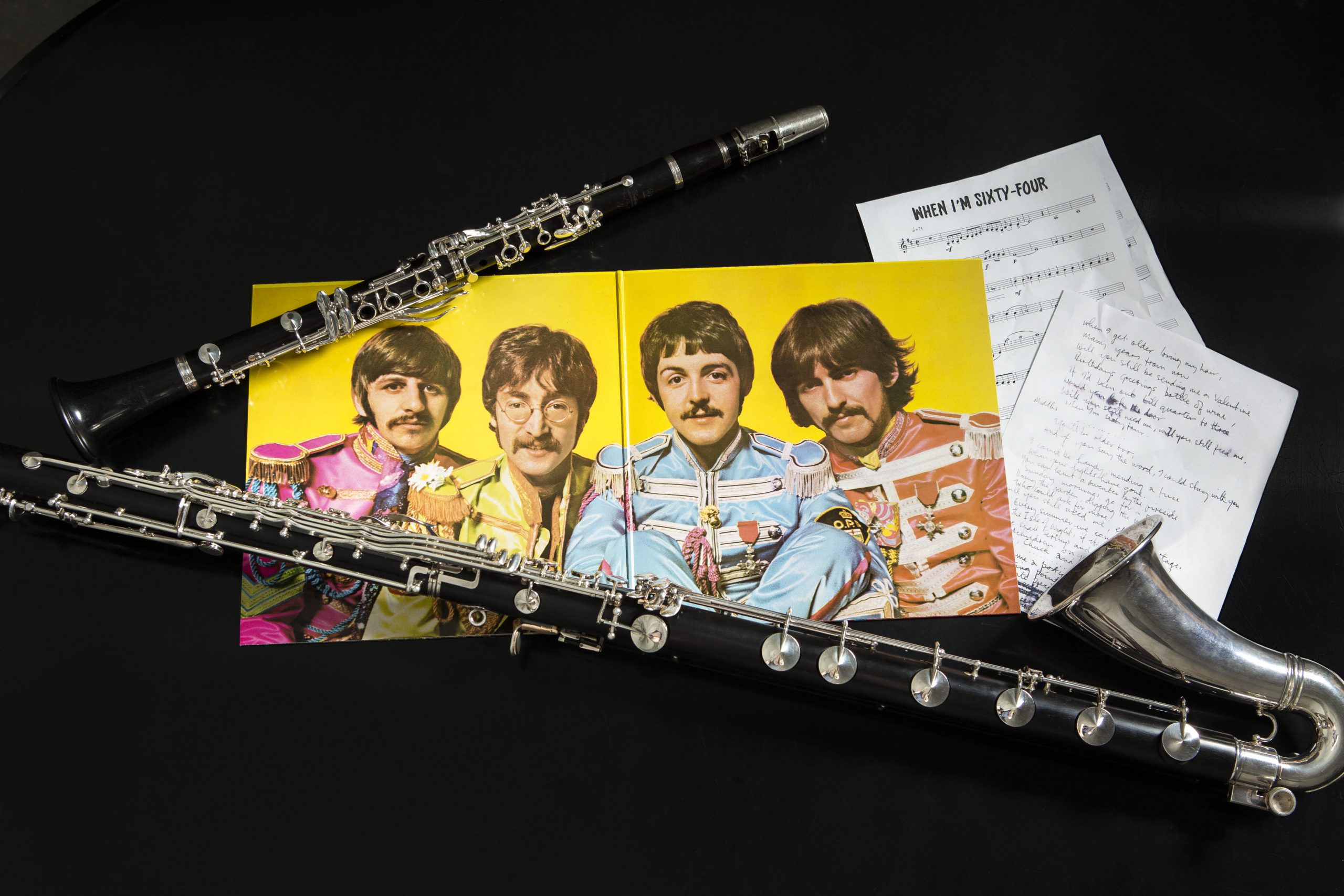

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

by John Reeks

“It was 50 years ago today…” (well, actually last summer): June, 1967 – the “Summer of Love.” While everyone seemed to be growing their hair long, donning beads and attending love-ins, short-haired, pocket-protector-wearing me was playing clarinet in the high school marching band, thus solidifying my nerd status. Compared to playing guitar like my friends, there was nothing cool about the clarinet, in spite of a brief period of street cred bestowed upon us by Pete Fountain’s television appearances in earlier years. The only thing I had in common with my cooler peers was a love for the Beatles’ music.

Some ancient history, for those of you who didn’t exist then: there was no internet, no Spotify, no CDs. There was much less promotional hype about upcoming music releases (phonograph records only), even for popular groups like the Beatles. The new songs would “magically” appear on Top 40 radio and in record stores.

All this explanation is to set the stage for that day in 1967 when I noticed a new Beatles album in the Sears-Roebuck record rack. I splurged for the more expensive stereo version ($3.69 instead of a dollar cheaper for monophonic sound) as my parents had recently purchased a stereo console.

I planned my first listening session of this album, titled Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, as a religious event. I waited until I was alone in the house, secreted myself in the room with the phonograph, turned off all the lights, lay on the floor and let the music wash over me.

Imagine my surprise when I flipped the album (yes, you had to do that, to hear both sides!) and the second song, “When I’m Sixty-Four,” began with a clarinet trio.

I sat bolt upright in the darkened room. How could this be? Were these some guitar sounds being distorted with studio trickery? No, they were clearly clarinets, and for the entire song!

All of a sudden, it was cool to be a clarinet player in high school band. The mantle of nerd-ism was lifted, thanks to the Beatles’ inventive use of instrumentation. But what brought about this momentous event in the evolution of the clarinet?

A Music History Lesson

“When I’m Sixty-Four” was the first song completed for the Sgt. Pepper album in December 1966.

The work, as Paul McCartney relates, was written at his home in Liverpool “when I was about 15. Back then, I wasn’t necessarily looking to be a rock ’n’ roller. When I wrote ‘When I’m Sixty-Four,’ I thought I was writing a song for Sinatra.”1

The Beatles began work on recording the song on December 6, 1966. The instrumentation is Paul on bass, Ringo Starr on drums and John Lennon playing some electric guitar phrases in the final verse. George Harrison was present at the session, but apparently did not participate in the recording. McCartney overdubbed some piano fills to complete the rhythm track for the evening, with no vocals yet.

The next session for “When I’m Sixty-Four” was on December 8. Paul used this session to record his lead vocals onto the existing rhythm track. The song was shelved for a while and they picked it up again on December 20. Ringo added his tubular bells solos while the other three worked on background harmony passages.

Where Did The Idea For Clarinets Come From?

It was around this time that Paul probably conferred with his producer about what was needed to finish the song. Recording engineer Geoff Emerick explains,

As was usual for a McCartney song, there were extensive discussions with George Martin about arrangement. Paul kept saying that he wanted the song to be really “rootie-tootie,” so George suggested the addition of clarinets.2

But why clarinets? George Martin said McCartney asked if he could possibly use clarinets “in a classical way” to “get around the lurking schmaltz factor.”3 McCartney later described the situation:

George helped me on a clarinet arrangement. I would specify the sound and I love clarinets so, “Could we have a clarinet quartet?” “Absolutely.” I’d give him a fairly good idea of what I wanted and George would score it because I couldn’t do that. He was very helpful to us. Of course, when George Martin was 64 I had to send him a bottle of wine.

McCartney didn’t get his clarinet quartet. Instead, Martin wrote an arrangement for two clarinets and bass clarinet, perhaps as a reference to his own orchestral background. It’s also an insight to Martin’s economical thinking, as he realized he could do what was necessary in the arrangement with three instruments instead of four. And although the song was written in a music hall style, it was not Martin’s first experience duplicating old-fashioned sounds. Martin had his first number one hit in Britain in 1961 with a rousing recreation of the 1920s sound on The Temperance Seven’s “You’re Driving Me Crazy.”

On December 21, 1966, the three clarinetists recorded George Martin’s score for “When I’m Sixty-Four.” Paul was surely at this session, as the clarinets were his request. Since these were top studio musicians, the session was completed in just two hours, from 7:00 to 9:00 p.m. “I remember recording it in the cavernous Number One studio at Abbey Road,” George Martin continues, “and thinking how the three clarinet players looked as lost as a referee and two linesmen alone in the middle of Wembley Stadium.”5 Although the session was actually held in the smaller EMI Studio Two, the analogy is still apt.

There are some very clever touches in the arrangement, beginning with the fact that the second clarinet enters during the introduction before the first clarinet. There are three verses to the song; the clarinets outline and reinforce the chords, with characteristic flourishes to add musical interest. The first two verses are straightforward, but on the third, the players are allowed to open up with some of their own jazz inflections. During the chorus (“Will you still need me,” etc.), an interesting texture is achieved when the two clarinets play legato quarter notes while the bass clarinet plays staccato quarters.

Although the music was recorded in C major, the released version was changed to D-flat major by speeding up the tape. According to recording engineer Geoff Emerick, this was done so McCartney’s “voice would sound more youthful, like the teenager he was when he originally wrote the song.”6 McCartney rationalizes, “I wanted to appear younger, but that was just to make it sound more rooty-tooty; just lift the key because it was starting to sound turgid.”7 Speeding up the tape also makes the clarinets sound brighter, hearkening back to the earlier days of recording when the rich overtones of the clarinet were difficult to capture on primitive equipment. Emerick explains further: “The clarinets on that track became a very personal sound for me; I recorded them so far forward that they became one of the main focal points.”8

First-call London studio musicians recording with Quincy Jones, Henry Mancini and conductor Bob Farnon in April 1964; back row (left to right): Frank Reidy, Bob Burns (clarinet), Cecil James, Anthony Judd (bassoons); front row: Johnny Scott, Phil Goody, Geoffrey Gilbert (flutes), Leon Goossens (oboe). Photo courtesy of National Jazz Archive, Great Britain

Who Were The Clarinet Players?

For the clarinet trio of “When I’m Sixty-Four,” three of England’s best reed players were hired: Robert Burns and Henry MacKenzie on clarinets, and Frank Reidy on bass clarinet. The musician contractor for the EMI Abbey Road Studio at that time was probably Laurie Gold. He would have used these three often before and knew that they were the top session players available.

First Clarinet

Robert (Bob) Burns was born in Toronto, Canada, in 1923. During World War II, he was a member of the Canadian Central Air Force Band, which brought him to Great Britain. He remained after the war and became a leading clarinet soloist, as well as doubling on alto and tenor saxes. Burns played in various dance bands, beginning with Denis Rose in 1945. He played with the Ted Heath Orchestra in 1948-49, and then spent many years with Jack Parnell’s ATV Orchestra.

In addition to the Sgt. Pepper gig, he had an impressive 50-year recording career, working with artists including Roy Eldridge, Annie Ross, Benny Goodman, Barbra Streisand, Guy Lombardo, The Manhattan Transfer, Mildred Bailey, Ralph Sharon and Ted Heath. Burns appeared in several British television series, including Off The Record (1958) and Jazz 625 (1964). He was chosen to play in an all-star band for the TV movie Love You Madly: A Salute To Duke Ellington in 1969. He is featured on numerous soundtracks, most notably Henry Mancini’s score for Charade (1963). He continued to play regularly with small groups in jazz clubs through the 1970s, and in the late 1980s he returned to Canada, where he died in 2000.

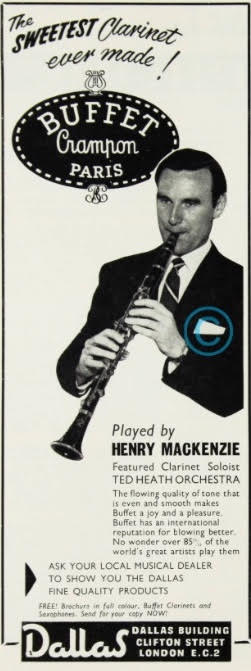

Advertisement from Crescendo Magazine featuring Henry Mackenzie, July, 1963. Photo courtesy of Buffet-Crampon and National Jazz Archive, Great Britain

Second Clarinet

Henry Mackay Mackenzie was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on February 15, 1923. After an aborted attempt to learn accordion, he settled on the saxophone. He played in various bands in his native Edinburgh before being called up for duty in an army band during the war. He served for five years before returning home to play in the Tommy Sampson Band. His solo clarinet playing attracted British bandleader Ted Heath who offered him a job with his group in London in 1949. Apart from a brief recall to military service in 1951, Mackenzie stayed loyal to Heath for 18 years, playing tenor saxophone in the section and solo clarinet. He participated in the band’s impressive array of broadcasts, recordings and concerts, and in its American and Australian tours. He often stole the show with his scintillating clarinet work, pure-toned and fluent. He recorded 23 albums with this band, plus numerous recordings with other groups.

After Heath died in 1969, Mackenzie branched out into session work as a first-call musician for Henry Mancini, Billy May and Nelson Riddle whenever they recorded in London. He performed regularly with various groups on BBC Radio, sometimes as a leader, sometimes a sideman. In addition to performing, Mackenzie also wrote and arranged music, including several albums of atmospheric pieces to be used on soundtracks, plus the film score for the motion picture The Babysitter (1980). Never short of work, he chose to retire while still in his prime in 1995. He died on September 2, 2007, in Carshalton, Surry, England.

Bass Clarinet

Frank Reidy was also one of the premier reed doublers in Great Britain from the 1950s through the 1980s. He was born on November 26, 1919. In his early years, he backed Peter Sellers and Spike Milligan on their Goon Show broadcasts. These programs were a great favorite of the Beatles, so they inadvertently heard Reidy as they were growing up!

Photo courtesy of Wikia, Inc

Besides playing with all of the leading bands during that time, his greatest exposure as a player was as the tenor saxophone “voice” for the character “Zoot” on The Muppet Show. He is featured on all 120 episodes. Reidy also was the musician contractor (“fixer” in Great Britain) for EMI Recording Studios, although this was after the Beatles’ years at that facility. He died in Camden, London in February 1996.

Burns, Mackenzie and Reidy all played together with each other on numerous occasions, both before and after the historic Beatles session. Burns and Reidy probably worked together a bit more, as Mackenzie played exclusively with Ted Heath for so many years. All three were featured in music magazine ads with the instruments they endorsed, and there are other articles in which they give advice on playing, equipment, etc. They were certainly the cream of the crop of British jazz clarinets during the 1960s and onward.

Having done the biographical research on these three amazing players, I also consulted with the great British saxophonist and composer Paul Harvey for some background information. He knew all three and graciously shared his memories with me in an email, remembering that Bob Burns was “definitely the most colorful character of the three.” Harvey praised his playing, not only as tenor sax soloist on Ravel’s Bolero with the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra but also as tenor sax in a concert with the Benny Goodman Band. Henry Mackenzie was, according to Harvey, “a brilliant jazz player and a most modest and self-effacing man.” Harvey told of how he made the sometimes-tedious job of soundtrack recording fun. Frank Reidy was “the top doubler.” Harvey continued: “He used to drive round in a Rolls Royce, the boot [trunk] stuffed with flutes, oboes, saxophones, etc. Not only did he become the fixer for EMI Studios, but also for Elstree Studios and for The Muppet Show.”

A Symmetrical Story

To bring things full circle, last year, when I turned 64, I produced a recital at Loyola University New Orleans titled, “When I’m Sixty-Four,” to celebrate my birthday. For the final work on the program, I recreated the Beatles’ arrangement, with two clarinets, bass clarinet, piano and chimes. I did the best I could on vocals. The nerdy clarinet player who first heard this song in a darkened room would be surprised and, I hope, proud of his 64-year-old self, celebrating his career on the clarinet.

And to top this story off, I was recently asked by noted Beatles historian Jason Kruppa to participate in his soon-to-be-released podcast, Producing The Beatles, for an episode about “When I’m Sixty-Four.” Using newly isolated tracks from the original recording, I transcribed the clarinet parts, which we then took into the studio to record. Just like with the original production, our three clarinets added their parts by listening to the lead vocal, bass and drum track for tempo – no click tracks existed in 1966. It was great fun to “play with the Beatles.”

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Paul Harvey for graciously giving background information for this article. Thanks also to James Gillespie for his encouragement, proofreading and longtime friendship. Special gratitude goes to Jason Kruppa for inspiring this research. His podcast Producing The Beatles gives great insight into how the Beatles used recording techniques and other instrumentalists to create their music.

Endnotes

1 Barry Miles and Paul McCartney, Many Years From Now (New York: Henry Holt, 1997), 72.

2 Geoff Emerick and Howard Massey, Here, There and Everywhere, My Life Recording the Music of the Beatles (New York: Gotham Books, 2006), 218.

3 George Martin and Jeremy Hornsby, All You Need Is Ears (New York: St Martin’s Press, 1994), 188.

7 The Beatles, The Beatles Anthology, 215.

About the Writer

The author, circa the release of Sgt. Pepper

John Reeks plays clarinet, bass clarinet and saxophones in the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra and is clarinet instructor on the faculty of Loyola University New Orleans. He serves as a Yamaha Performing Artist and a Ligaphone Artist. His clarinet teachers include Vito Platamone, Robert Marcellus and Stanley Weinstein.

Comments are closed.