Originally published in The Clarinet 52/4 (September 2025).

Copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

Cultivating Belonging Among Underrepresented Students Through Repertoire

This two-part article investigates perspectives on inclusion and belongingness by Black clarinetists, and then examines three works by Black women composers and their potential use in clarinet pedagogy.

by Jennifer Woodrum

PART 1: PERSPECTIVES FROM BLACK CLARINETISTS

In 2022, I interviewed three prominent Black clarinetists as part of my research on works for clarinet and piano written by Black composers: Marcus Eley, Nicholas Lewis, and Mariam Adam. The three participants shared with me some of the ways that being in the primarily White spaces of educational and performance institutions were challenging for them as Black musicians. One of the emergent themes of these conversations was that having access to repertoire by Black composers had a transformative impact on their affirmation of identity and sense of belonging within the context of their training, study, and eventually, their careers.

The applied teacher is the singular professor that requires a weekly hour of one-on-one individualized instruction. That one hour can be extremely vulnerable for the student, constantly being assessed on weekly progress and receiving feedback about how they have prepared. This structure of focused time and dedicated space inherently holds the potential for enormous musical and personal development, including when it comes to cultivating a sense of belonging.

Students that do not fall within the identity profiles of the majority— because of traits such as gender, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic background, religion, or physical ability—can be empowered with an increased sense of belonging in the repertoire choices that they have available to them.

In approaching repertoire selection with the intention of representing as many identity traits as possible, the applied teacher engages in an act of resistance to the way things have always been done and works toward the future that we all know is possible for classical music. Nicholas Lewis shared,

What I consider a part of the beneficial legacy of classical music is how people are trained. There is something about the relational dimension to education that is so incredibly important, not just transacting of information… I recognize, also, it is my role to help foster this space for others in ways that go well beyond the transactionality of the information.

Comparing one-on-one applied teaching to large lecture or classroom teaching, there is a tremendous opportunity—and, I would argue, responsibility—to be inclusive with a great sense of intentionality. In teaching musical content alongside cultivating a sense of belonging for every student, a lifelong relationship of support between teacher and student flourishes.

BELONGING

In a keynote speech for the 2024 Cultural Connections by Design National Conference, Dr. Nicole R. Robinson defined belonging as the feeling of being accepted, valued, and included within a community or group, where individuals feel comfortable being their authentic selves and contributing their unique strengths.1 Robinson went on to state the following:

Within a “culture of belonging” framework, individuals connect and contribute meaningfully, authentically, and uniquely to the overarching goals and values of the space. You see, when I step into a space that is centered with a culture of belonging, I can bring my complete, unreserved self into the space, offering the very best of what I can contribute.

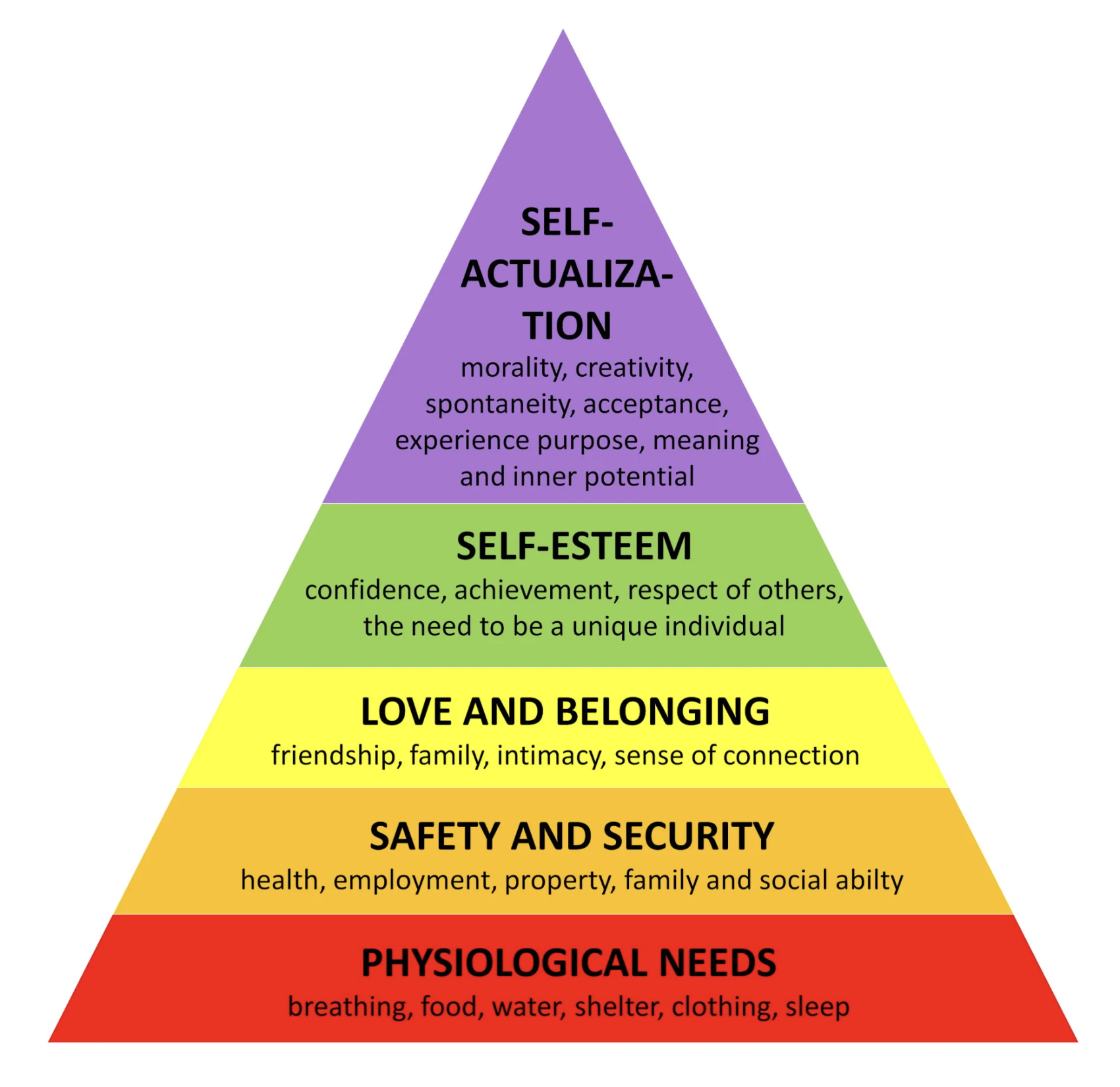

In 1943 Abraham Maslow included “belonging” as one of the most fundamental needs in his Hierarchy of Human Needs. The pyramid format in Figure 1 illustrates the most basic human needs starting at the bottom with physiological needs, including elements such as food, water and sleep. Moving up a level are safety needs or feeling a sense of physical and emotional security. Just above the need for physical safety is belonging, followed by esteem, which can be thought of as feeling respected and respect for others.

According to Maslow, the first four needs—physiological, safety, belonging, and esteem needs—qualify as deficiency needs. Without having these needs met, human beings are not able to access motivation toward achieving the higher-level needs; their primary focus will be on moving out of deficiency. The higher-level needs include cognitive (creativity and curiosity), aesthetic (appreciation of beauty in self, surroundings and nature), self-actualization (realizing one’s potential), and transcendence (spiritual needs).

Figure 1: Maslow’s Motivation Model2

CULTIVATING BELONGING: REPERTOIRE BY COMPOSERS WITH SHARED IDENTITY

In saxophonist Steven Banks’s 2018 Ted Talk, he discussed how he spent most of his musical training struggling to find a sense of belonging in a field where no one else looked like him, playing the music of composers that didn’t look like him, in spaces where he was “not only the only Black person in the room, but the only person of color.”3

For many students of color, the love of classical music is met with a message of “You do not belong here,” a message that is inferred from the cultural and ethnic backgrounds of the people that occupy the rehearsal and performance spaces, and the repertoire that is suggested or often required to be performed. During Banks’s 14 years as a student of classical music, he played a total of three works by Black composers.

Marcus Eley shared about an experience in college when he visited the library to check out some musical scores that had been recommended to him by his mentors, Dr. Dominique-Rene De Lerma and David Baker:

At Indiana University in the late ’70s, early ’80s, I went into the music library, and I could literally dust off books and scores that had never been checked out. So, I would bring these pieces in and my teacher would say, “Well, we need to go to the French repertoire, through all of the genres and all these studies, but if you want to do this on your own, that’s your choice.” Because of the experience of having people like Dr. De Lerma and David Baker there as my mentors, they opened my mind.

Eley’s applied teacher did not encourage his interest in exploring works by African American composers. However, the relationship that Eley had with mentors, combined with his persistence, led to him forging a career path dedicated to developing relationships with Black composers and recording their works.

When I asked Mariam Adam to describe what she sees as the relevance of students playing repertoire by composers that share their racial or cultural identity as part of their training, she responded,

A musician needs to have something they identify with. And if they can identify with something culturally, all the better. Repertoire is everything.

Adam lives this truth out in her career path as a founding member of Imani Winds and the TransAtlantic Ensemble, both thoroughly dedicated to championing the works of composers of color.

Nicholas Lewis’s sense of belonging within music, like his identity, is very directly linked to his family and the Black community. Nicholas was always passionate about promoting the works of Black composers and this was encouraged by his applied teacher.

On my senior recital back in 1994, the very first thing I did, I sat at the piano and played “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” I made everybody stand up and sing it. I did this to honor my parents and my family that showed up and all of my ancestors who were not there.

Lewis also shared about his experience curating a radio series as Multicultural Arts Initiative Producer in 1997 for WQEB in Pittsburgh:

It was called the African American Music Tree—not incredibly aptly named. It was really looking at the 400 years of contributions of Black peoples throughout the diaspora, not just African American people, to the history of Classical music. In a four-part, one-hour series, it was talking about the contributions of Black people to this thing we call Classical music. I mean, it was clear that Black people had contributed in every century of the enterprise, at least going back to the 17th century.

Lewis has never questioned that Black people have made enormous contributions to classical music, but he has been frustrated throughout his career with how little music by Black composers is programmed by the institutions he has directly been involved with and as a consumer of classical music. He explained,

You know, when orchestra committees are left to program on their own, are they thinking about composers of color? Women composers? No, they want to play all the hits and the highlights.

Throughout my conversations with these three clarinetists, our collective hope for the future is systemic change. Rather than relying on mass social upheaval in order for organizations to make statements and take action, we envision people creating solutions that are embedded into the day-to-day operations of systems, policies, and curricula.

PART 2: THREE WORKS FOR CLARINET AND PIANO BY BLACK WOMEN COMPOSERS

To amplify and celebrate two identity traits that are not historically as represented on clarinet studio recommended repertoire lists, I am choosing to highlight three works for clarinet and piano by Black women composers.

Within each of the following piece descriptions, I provide a pedagogical context in which these pieces could be used. That context is within the framework of standard repertoire selections. I am by no means implying that any of the standard repertoire mentioned below be replaced, but rather that we choose to weave in beautiful new fabric into an already vibrant and rich tapestry.

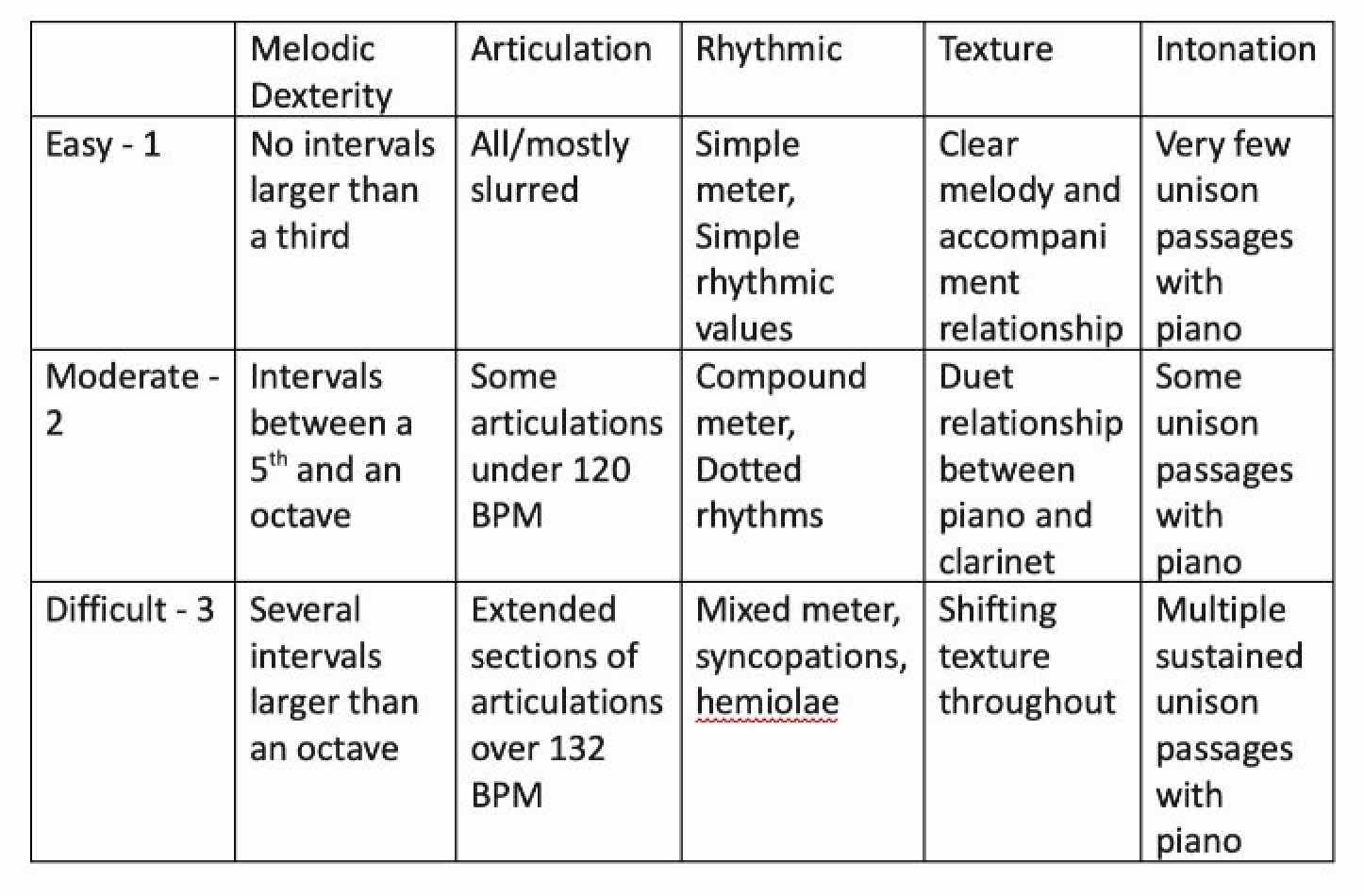

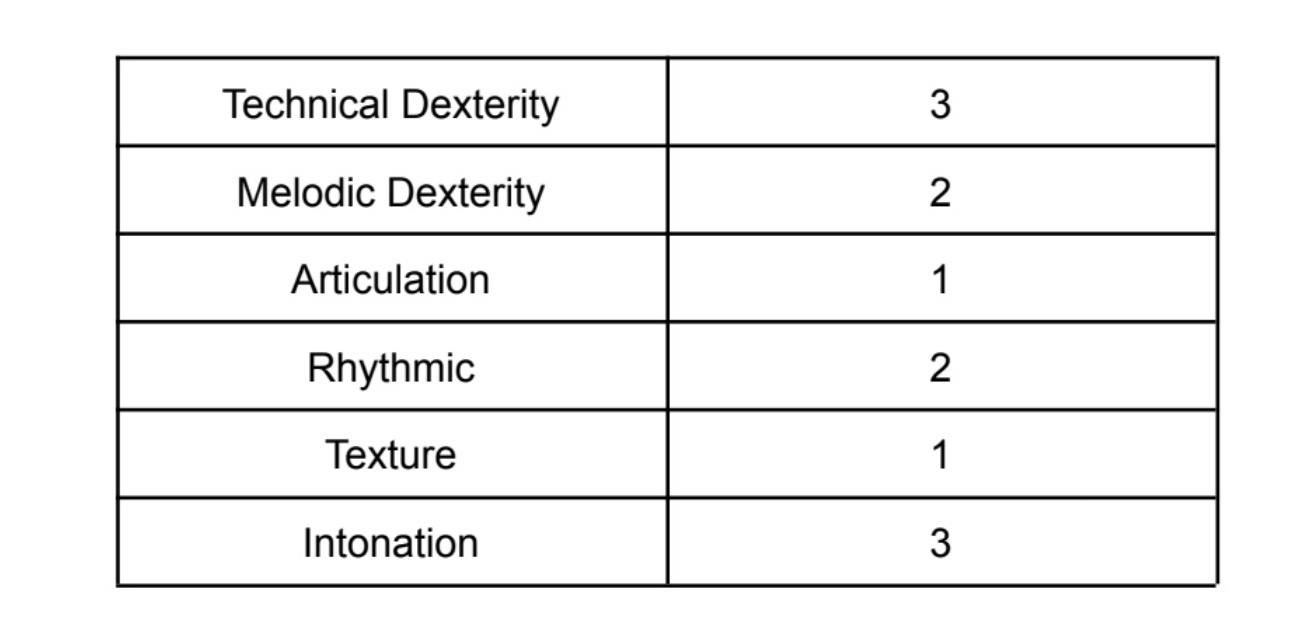

I have created a graded rubric for each piece based on the following:

- Technical dexterity: Speed of technical passages

- Melodic dexterity: Range of melodic intervals

- Articulation: Articulation tempo requirements

- Rhythm: Level of rhythmic complexity of solo part

- Texture: Rhythmic complexity between clarinet and piano part

- Intonation: Pitch difficulty between clarinet and piano parts

Each of the five criteria are graded on a scale of 1 to 3 from easy to difficult (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Rubric

VALERIE COLEMAN, SONATINE FOR CLARINET AND PIANO (THEODORE PRESSER COMPANY, 2014)

Length: 8:10

Number of movements and tempi:

One movement, quarter = 120

Range: low F to altissimo E

Extended techniques: None

Recommended student level:

Undergraduate/Graduate

Recordings available: Transatlantic

Ensemble, From the Americas

Composer website:

www.vcolemanmusic.com

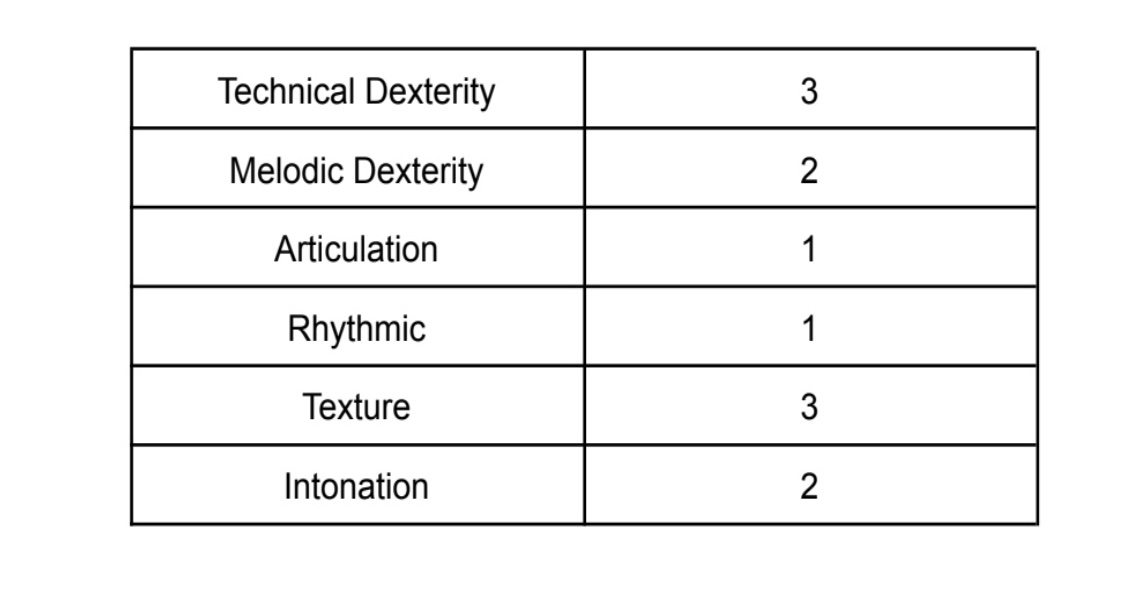

Figure 3: Rubric for Sonatina by Valerie Coleman

Valerie Coleman’s Sonatine was inspired by her time touring through Europe. On her website, she describes the work as “reminiscent of a performance at a nightclub where players wailed soulful tunes and riffs on a lovely summer evening in Berlin.”4 This comes through in the many directions the melodic material takes the listener, in one measure playing a beautiful lyrical gesture, and in the next a string of complicated 16th notes. The jazz language comes through in the harmonies, the highly syncopated and polyrhythmic vocabulary, and the sophisticated development of melodic material.

This very efficient piece could accomplish similar pedagogical goals as the Sonata for Clarinet by Leonard Bernstein or the Darius Milhaud Sonatine for Clarinet and Piano. Coleman’s Sonatine gives clarinetists the opportunity to engage in highly complex rhythmic writing with a piano duo partner. Less experienced student clarinetists should be prepared to study the score thoroughly and to plan for extra rehearsal time with the pianist.

Valerie Coleman’s Sonatine was premiered in 2006 by the TransAtlantic Ensemble (Mariam Adam, clarinet and Evelyn Ulex, piano).

Figure 4: Excerpt from Sonatine by Valerie Coleman

LAWREN BRIANNA WARE, THE FEATHERHEART (B. WARE WORKS PUBLISHING, 2016)

Length: 05:20

Number of movements and tempi:

One movement, quarter note = 60

Range: Low G to altissimo A

Extended Techniques: none

Recommended Student Level:

Advanced high school/undergraduate

Recordings available: The Featherheart for clarinet and piano, World Premiere at AEIVA

Composer website:

www.lbwaremusic.com

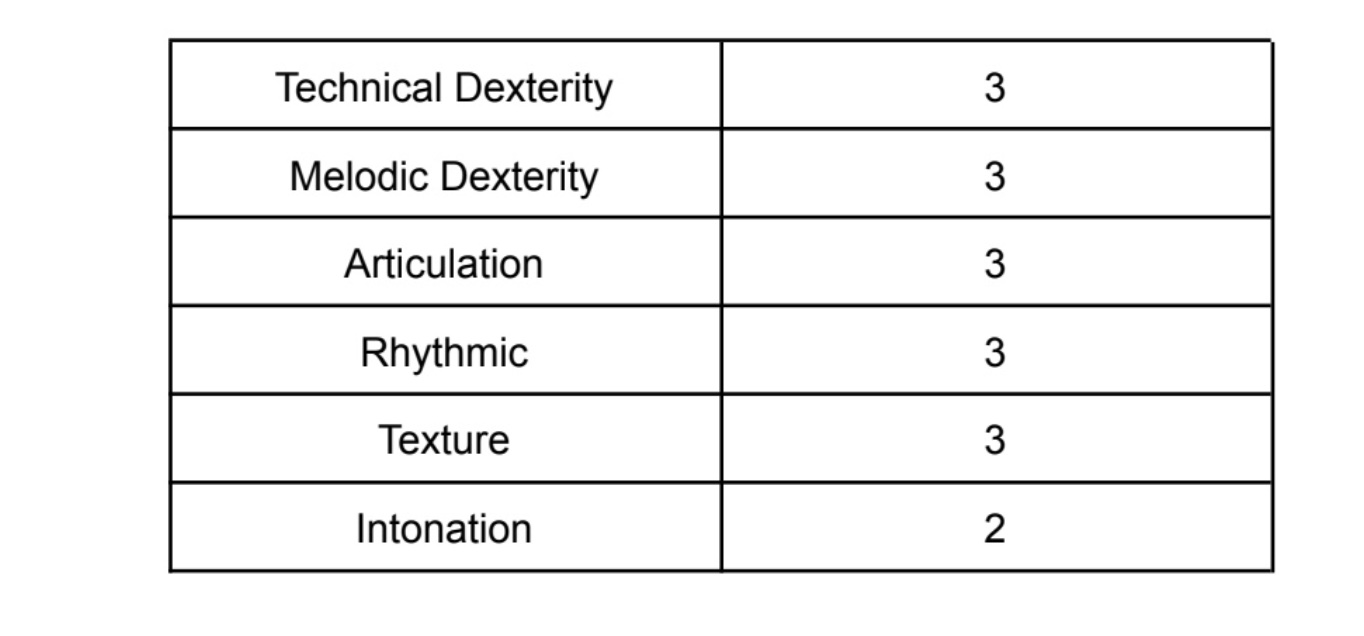

Figure 5: Rubric for The Featherheart by Lawren

Brianna Ware

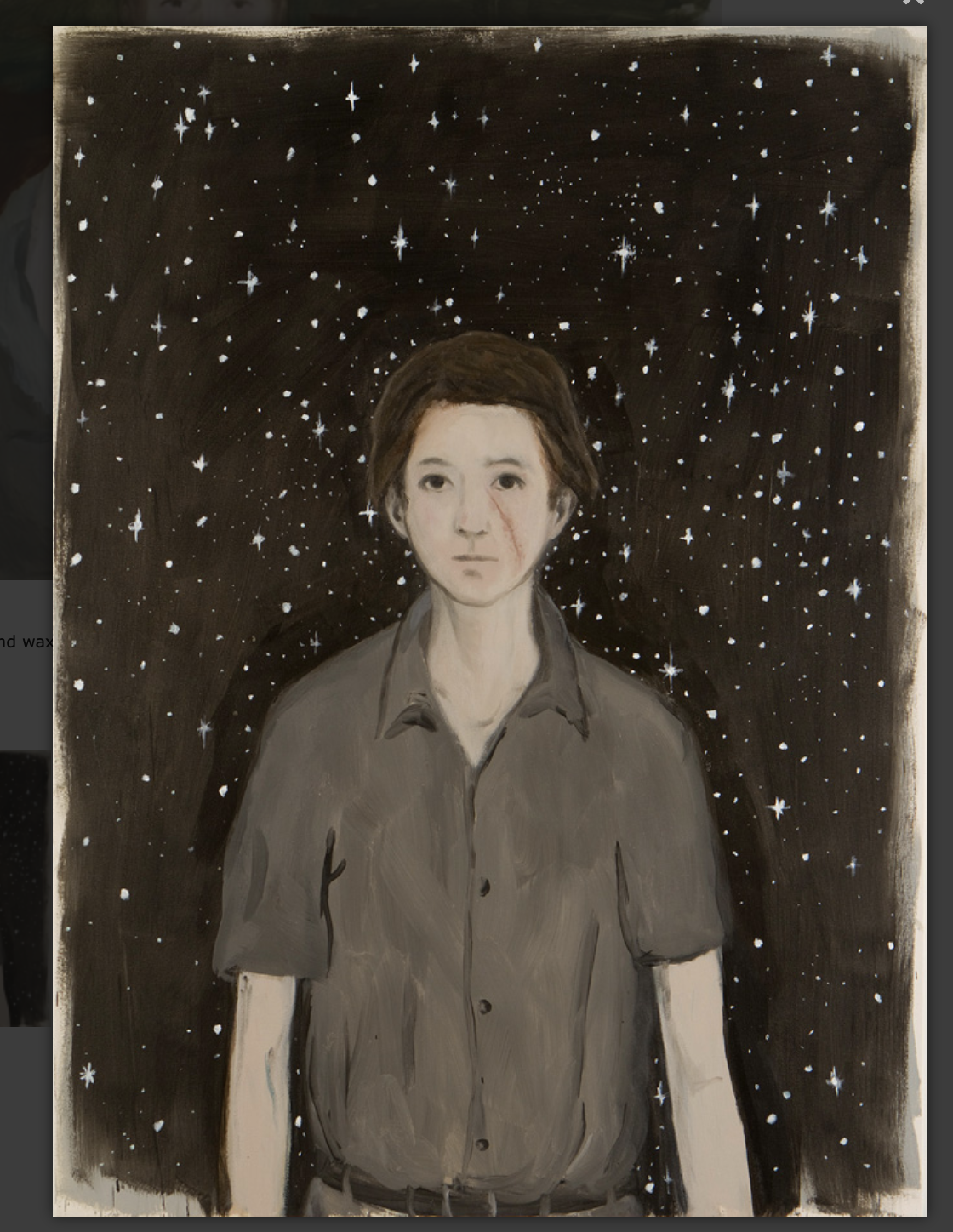

Given this piece’s direct link to a work of visual art, I have chosen to provide program notes from the composer:

My composition was inspired by Mr. Enrique Martinez Celaya’s work “The Featherheart” (and thus, my composition is named after this piece of art). The painting depicts (what I believe to be is) a young woman who has a scar on her left cheek. Behind her, one can see the dark night sky and stars. If you look closely, her scar seems to be in the shape of a feather. To me, the woman seems to be one who has a past that is full of sadness, trials, and many difficulties. She may even have a history of abuse (thus, the scar on her cheek). However, there seems to be a glimmer of hope in her face for a brighter future. I wanted to create a piece that was calm, ethereal, and emotional. I wanted to convey what I believe is the woman’s story: one of sadness and hurt, but also one of hope. I chose the instrumentation of solo clarinet and piano. The clarinet’s wide range of notes and dynamics is representative of the woman’s voice. The piano accompaniment is meant to feel free and ethereal. The descending pattern that begins the piece (and later returns in both the piano and the clarinet), along with the tuplets/glissandi, are intended to represent a floating feather. It is also representative of the twinkling stars that are in the background of the painting.

Figure 6: “The Featherheart” by Enrique

Martinez Celaya

The Featherheart would be an excellent selection to prepare a student to play Debussy’s Premiere Rhapsody. This piece artfully challenges lyricism with passages of 16th and 32nd notes within long phrases utilizing the full range of the instrument.

The overall mood of the piece is introspective. Opening with the piano establishing beautiful, hopeful harmonies in a descending eighth-note line, the clarinet emerges from the texture with sustained phrases that eventually lead into more virtuosic passages. Ware skillfully works the listener’s ear inward toward heavier and darker emotions, peaking with dissonant tonal clusters in the piano in the middle of the piece. The piece winds down with elongated note values in both instruments, setting up a rhythmic ritardando that concludes with major harmonies that inspire feelings of optimism and hope.

The Featherheart was premiered in March 2026 by clarinetist Brad Whitfield and pianist Chris Steele at the Abroms-Engel Institute for Visual Art at the University of Alabama – Birminhgam.

Figure 7: Excerpt from The Featherheart by Lawren Brianna Ware

ELEANOR ALBERGA, “DUO” FROM DANCING WITH THE SHADOW (ELEANOR ALBERGA SCORES, 1990)

Length: 04:52

Number of movements and tempi: One movement from a larger chamber work, quarter = 104/144/116

Range: low E to altissimo E

Extended Techniques: two measures of repeated fingered quarter tones

Recommended student level: Graduate

Recording available: Eleanor Alberga, Dancing With The Shadow (1990)

Composer’s website: https://eleanoralberga.com

Figure 8: Rubric for “Duo” from Dancing with the

Shadow, Eleanor Alberga

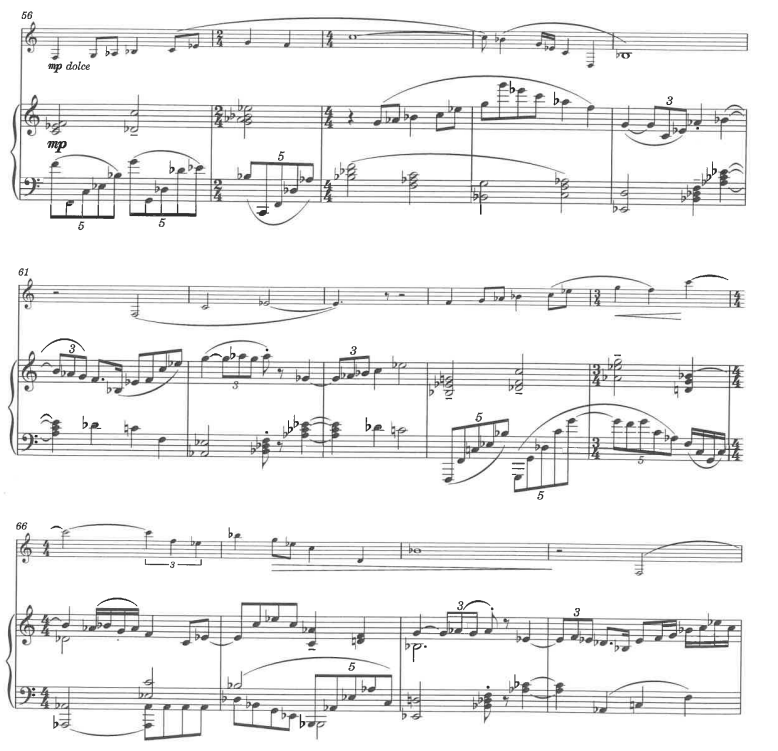

Featuring syncopated rhythms within the context of mixed meter and rapid tonguing, Eleanor Alberga’s “Duo” from Dancing with the Shadow provides similar pedagogical opportunities as Stravinsky’s Three Pieces. Extended passages with mixed meter and syncopated rhythms would challenge an advanced clarinetist. The middle section features exploration of lyricism within register changes, trills, and microtonal fingerings intended to depict a digeridoo.

Alberga’s “Duo” from Dancing with the Shadow is taken from a larger work scored for flute, clarinet, violin, cello, piano, and percussion. The piece was commissioned and premiered in 1990 by Lontano Ensemble in the UK as a work for chamber ensemble and dance. The entire work is 30 minutes long and can be purchased in its complete version or as only the “Duo” movement for clarinet and piano.

The first movement, “Duo,” stands solidly independent from the rest of the piece as a duo for clarinet and piano, in a satisfying ABA form. The clarinet begins the piece alone, for the entire first page, before being joined by the shadow, the piano. When the piano joins as the shadow, it plays with the skipping melodic gestures initiated by the clarinet, lengthening, fading and occasionally disappearing (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: Excerpt from “Duo” from Dancing with the Shadow, Eleanor Alberga

THE FUTURE OF CLASSICAL MUSIC IN THE UNITED STATES

At the conclusion of each of the interviews, I asked each participant to describe their dream for the future of the classical music field in the United States. In their own words, each participant shared that they look toward a future where diversity, both in programming and the people who make up the institution, is recognized as an asset for the longevity of an institution, organization, field of study, and art form (and not only from a funding perspective).

The unanimous response regarding the vision for the future was “that we don’t have to do this anymore.” In other words, we hope for a future wherein there is no longer a need to have conversations and implement initiatives centered on diversifying the makeup of our institutions and programming because the diversity is already there.

When I asked Marcus Eley to describe his vision for the future of classical music, he replied,

I feel that is my challenge, my responsibility, my legacy, that I do something to make it more inclusive, to make sure that these works get performed to the point that we don’t have to think about the works by African-American or women composers. There’s just music.

Eley just released his fourth full-length recording of works written by African-American composers on Novona Records, That’s a Different Groove, featuring works by Alvin Batiste, David N. Baker, Yusef Lateef, and Oliver Nelson. Through recordings, articles and programming, he has fully dedicated his career to doing what he interprets as his part for the future of the classical music field.

Mariam Adam has served on many committees, in Europe and the United States, that are working to address the lack of diversity in classical music. She shared her hope for the future:

I hope that there can be a concentration on problem-solution, and that it isn’t a quick fix. I hope the solutions can be the focus, and that the people who are already making a difference can be the focus.

Nicholas Lewis stated,

Black people have always existed as the purveyors and as the creators of this music. And so it is purely a condition of poor scholarship on the part of the school or irresponsibility, as the sort of cultural purveyors, to effectively miss out on so much of the richness particularly in a US context, which is to say, a context of hybridity. And so, you know, to the extent that we frame concerts around masterworks and, you know, specifically taking language that comes out of all kinds of supremacist sort of enterprises, it says a lot to how it is that we allow classical music to exist. We allow it to be White and it is not. It’s German, it’s Austro-Prussian. It’s French. It’s Russian. It’s Ukrainian. And it’s also really Black.

As lived and eloquently stated by all of the clarinetists interviewed, music by Black composers is abundantly available. It is the responsibility of those that hold the power of programming and repertoire curriculum decisions to ensure that it is brought to the forefront. The repertoire that institutions champion speaks volumes about who belongs in their spaces. If classical music is to become the diverse and equitable entity that has been a focus of so many initiatives over the past 50 years, the people that reside in these communities need to know, without a single doubt, that they belong.

It is my hope that this article empowers readers to use these conversations and recommended strategies as a way to recognize and express value for the unique identities of each of their students, and cultivate the qualities that will support all of their students to reach their true and full potential.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

For more information on repertoire for clarinet and piano by black composers, see my full dissertation A Pedagogical Resource of Works Written for Clarinet and Piano by Black Composers – Post 1980.5

Institute for Composer Diversity – This database features intuitive search functions, wherein you can search through specific categories. To search for music for clarinet and piano, for example, select Chamber Database from the Home Page, Solo with Piano from the Ensemble Size Dropdown menu and then select works for clarinet and piano.

No Broken Links – This growing online database is managed by multidisciplinary artist and composer Brandon Scott Rumsey. The database is a Google Sheet housed on Rumsey’s website and features repertoire by marginalized composers for flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, saxophone and french horn. Each instrument has its own tab, including listening and sheet music purchasing links.

ENDNOTES

1 Nicole R. Robinson, “2023 National Conference Keynote: The Right Environment: Creating Belongingness in the Classroom,” Cultural Connections by Design National Conference, June 1, 2024, accessed July 22, 2025.

2 Saul McLeod, “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Human Needs,” Simply Psychology. March 14, 2025, accessed July 24, 2025.

3 Steven Banks, “Into the Canon: Equity in Classical Music,” TedX Northwestern University, September 13, 2017, accessed June 7, 2022.

4 Valerie Coleman, “New Creations,” Valerie Coleman: Composer, 2022, accessed May 11, 2022.

5 Jennifer Woodrum, “A Pedagogical Resource of Works Written for Clarinet and Piano by Black Composers – Post 1980” (DMA diss., Northwestern University, 2022).

Comments are closed.