by Amy D. Simon and Gerard Yun

Introduction

Gerard Yun playing shakuhachi (Photo by Natasha Choo)

The fourth movement of Eric Mandat’s Folk Songs for solo clarinet (1986) is titled “With devotion, like a prayer” and is imitative of the Japanese bamboo shakuhachi flute. The shakuhachi was used in Edo-period Japan as a meditation implement by itinerant Zen Buddhist samurai-monks. Today, various schools and styles of playing continue in Japan and around the world with their own canons of repertoire, among them Kinko, Tozan and Meian. The shakuhachi has also received attention from modern Japanese composers such as Takemitsu Tōru[1] and has been popular in the West since the 1960s, inspiring imitative works such as Mandat’s.

Masters and students of the shakuhachi approach it as a tool for cultivating the breath and some do not consider it a musical instrument at all. Nor do they consider their playing to be performance. One popular Rinzai Zen master, Watazumi Fumon (1911-1992), purportedly said, “If it sounds like music, you’re doing it wrong.”[2] Watazumi’s spiritual approach to the repertoire is one of the main forces that attracted shakuhachi students outside of Japan in the 20th century. Cultivation of the breath (both inhalation and exhalation), exploration of timbre, and aesthetic of “a single tone” (without any need for accompaniment or underlying harmonic implications) are primary in executing a “performance” of shakuhachi repertoire.

Mandat has notated many of the repertoire’s aesthetic qualities in his composition, but in order for the clarinetist to move beyond the score and capture them, a modest understanding of traditional Japanese aesthetic values is essential. Certain norms of staff notation and technique should not be taken for granted. These include the production of vibrato and pitch-bending, the approach to time in the rests between phrases, the articulation of tones with the tongue, and subtleties of timbre. This article is meant to guide the clarinetist through a more culturally sensitive interpretation.

Timbre

Neutral head position (kari) on clarinet joint

To capture a closer imitation of the timbre of the shakuhachi (Audio Example 1) than the traditional clarinet could provide, Mandat asks the clarinetist to remove the mouthpiece and barrel and blow across the upper joint, as one might do with a plastic bottle, using a flute-type embouchure. Since this shortens the clarinet, the acoustics of the instrument are altered and the scale greatly affected. Mandat thus provides unconventional fingerings to produce the desired pitches and special timbral effects and notates both how the tones should be fingered (lower staff in the musical examples) and how they should sound in B♭ pitch (upper staff).

Audio Example 1- Timbre of the shakuhachi (all audio examples by Gerard Yun)

Unlike most of Western music, where melodies are shaped by progressions of notes, the honkyoku (meditative solo music) of the shakuhachi is dominated by the aesthetic of a single tone. The shakuhachi is a Zen Buddhist instrument and its playing aesthetic is informed by Buddhist principles, of which two are of primary importance. The first is embodied in the phrase ichion-jobutsu, literally, “become the Buddha in one,” and translated to mean, “the attainment of enlightenment through perfecting of a single tone.”[3] The focus on a single tone mirrors the Buddhist meditational practice of focusing the mind into a single point. In actual practice, while the single tone (i.e., a sustained tone) does not alter in pitch, it does in fact change in timbre and intensity throughout. Depending on the tradition and playing style of a passage, there are prescribed ways to start, hold and end notes. While there is typically more than a single note per shakuhachi passage, with some being notoriously virtuosic, the single tone becomes the focus, or main tone, while the other notes comment upon it, providing relief or space around that note.

That sense that the sound is in relief to something else brings us to the second Buddhist principle of shakuhachi practice, the concept of ma, or nothingness. Takemitsu explains that ma is more than a gap between notes. It is the silence that empowers the sound of the shakuhachi itself:

the unique idea of ma—the unsounded part of this experience—has at the same time a deep, powerful, and rich resonance that can stand up to the sound. In short, this ma, this powerful silence, is that which gives life to the sound and removes it from its position of primacy. So, it is that sound, confronting the silence of ma, yields supremacy in the final expression.[4]

Imitation of the shakuhachi’s timbral aesthetic can be partially achieved through changes in head position. Common practice in traditional shakuhachi repertoire involves changing the angle of the breath against the mouthpiece through head position, thereby altering pitch and timbre. Lowering the head position lowers pitch and is called a meri position; the opposite is kari, and can indicate either a return to a neutral head position after meri or a raised head position. The shakuhachi has only five tone holes, resulting in an anhemitonic pentatonic scale, but meri-kari head positions, along with part-holing, are used to expand the available pitch resources to include semitones and microtones. Most significantly, these head positions offer the performer greater timbral possibilities. Meri tones tend to be softer, more muted, and breathier than kari ones (Audio Example 2). Whereas performers of the Classical Western canon tend to strive for uniformity of tone, shakuhachi master Riley Kelly Lee explains that “the shakuhachi performer does not attempt to minimize differences in timbre between meri and kari notes. Instead these differences are not only considered desirable but even essential for the correct performance of the music.”[5]

Audio Example 2- Meri and kari

The blowing edge on the top joint of the clarinet is primitive compared to the handcrafted utaguchi blowing edge on the shakuhachi; however, meri-kari is nonetheless possible. On shakuhachi, the head can be lowered in different ways to achieve meri effects: straight down, diagonally to the left, diagonally to the right, almost horizontally, etc. On the clarinet joint, lowering the head diagonally seems to give the best results. Each player should experiment with this on the left and right sides to find his or her most responsive spot. It is important that a tone be maintained as the clarinetist practices moving between kari and meri positions. In later sections, we will point to specific measures where a meri position would be appropriate, particularly in reference to vibrato and pitch bending as well as some phrase endings.

Breath noise is also appropriate in imitation of the shakuhachi timbral aesthetic and need not be refined away, but rather controlled and performed in a purposeful manner. In particular, measures where Mandat indicates sfz (e.g., m.25, beat 1- Example 9) or a crescendo to ff (e.g., m.28- Example 10) could be colored with extraneous breath sounds. In shakuhachi this particular technique is called muraiki, which translates to “the billowing breath.” Multiple simultaneous timbres (i.e. breathiness, reedy tone, and flute tone) are possible and desirable in traditional shakuhachi playing so muraiki, or in the case of this work “breath sounds,” are overlaid onto the existing pitches. Playing the “breathiness” is part of the music itself and requires awareness of the musicality of both the breathiness and the underlying pitches. In Mandat’s composition, breath noise could also be added to the opening grace note figure of m.20. In contrast, key noise should be absent throughout the movement if possible, as the shakuhachi has no keys, with extra care taken in mm.33 (Example 11) and 36 (Example 12).

Phrasing and breath rhythm

Although some repeated patterns in traditional shakuhachi repertoire are notated and played in relatively fixed rhythm, the overall approach to rhythm and phrasing is based on the breath of the performer. Each phrase is performed in one breath, with tempo and rhythm thus affected. Regarding imprecision of durational values, Lee explains, “in the performer’s mind, a note with a ‘long duration’ is held a ‘long time,’ not ‘four seconds’ or ‘eight seconds.’ How long the note ends up being held depends upon the circumstances of the individual performer and performance.”[6] This applies not only to note values but also to the temporal intervals between phrases as an expression of the aesthetic spatial concept of ma.

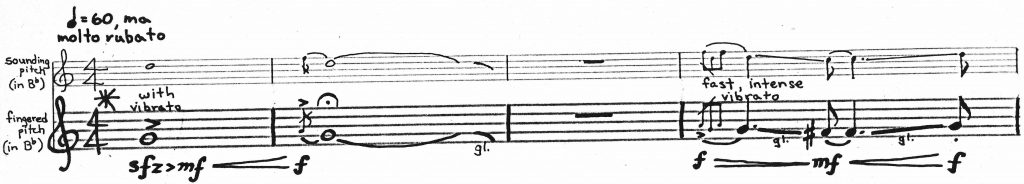

Mandat notates rests to indicate the beginnings and ends of breath phrases, i.e., the space between them. (In traditional shakuhachi notation these moments are simply understood.) For example, the first breath phrase spans mm.1-2, with each whole note lasting approximately half of the breath (see Example 1). It is not necessary for the clarinetist to count a strict ♩= 60 tempo here, but rather to sense the halfway point of the breath. Likewise, the full-measure rest that follows is not a break in the music, but space for the performer to move from exhalation to inhalation, and from phrase to phrase. Again, this need not be strictly measured. This approach to time and the breath leads the performer to cultivate an awareness of his or her breath and should be maintained throughout the piece.

Articulation

In traditional Japanese wind performance practice, tones are articulated not with the tongue but with the fingers. Thus the clarinetist’s instinct to tongue the beginning of each unslurred note in Mandat’s score should be ignored. The tone should be started with the breath alone, and with the fingers as indicated. Mandat notates grace notes at the beginning of many of the breath phrases and tones—these function as articulation devices. In shakuhachi terminology, this finger articulation is called atari (or utsu, i.e., to strike or to hit) and is mostly unwritten in the scores. Not all tones nor phrases need begin with atari, but many do (Audio Example 3).

Audio Example 3- Atari articulation

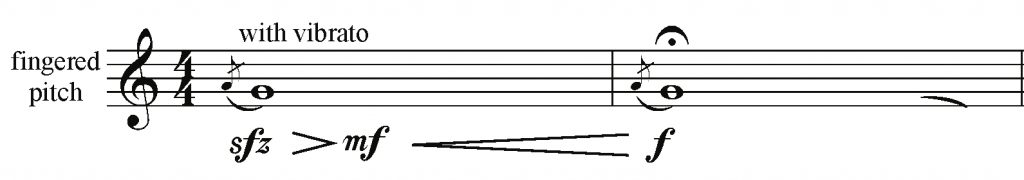

For the performance of Mandat’s movement, we have some additional suggestions for idiomatic atari figures: 1) Mandat indicates an accent over the first note of m.1, along with a sfz. To replace the clear beginning that tonguing the note would provide, we suggest an atari from the throat A4 fingering (see Example 2). The execution of atari should be quick and functional, without lingering. 2) For the triplet figures in mm.14-15, the performer could add a fingered chalumeau B3-C4 atari before the second and third B3 of each triplet (see Example 6). The tones of these atari need not register with the ear; the purpose is articulation rather than melodic ornamentation. Also consider a brief break in the sound directly after the glissando at the end of m.13, before beginning the triplet figures. 3) In m.33, it is appropriate to atari the first note with the same unconventional fingering that appears later in this measure for a raised chalumeau A3 fingering. The last note in m.34 can be played as written, or alternatively with an atari that mimics the preceding gestures. (See Example 11.)

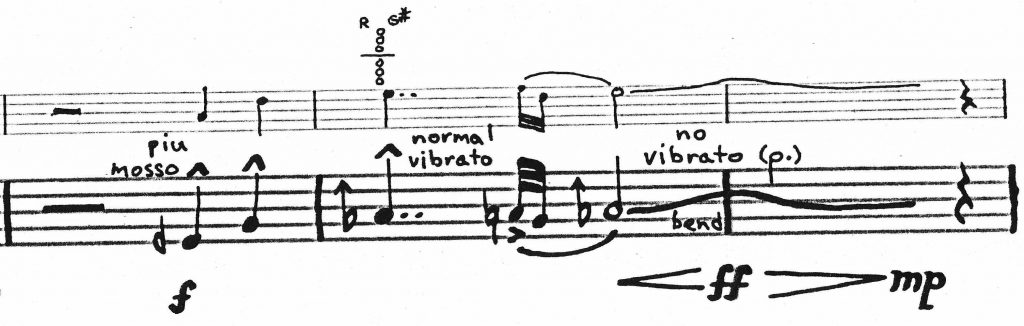

Regarding notated accents, these should be done with the breath instead of the tongue. The accent in m.1 has been addressed above, and those in m.27 (Example 10) could be approached similarly, with an A4 atari added to the fingered open G4, followed by a breath accent on the next note. We suggest treating the accents in m.7 with gentle breath pulses, and again, no tongue (see Example 4). As discussed above, Mandat notates a sfz at the beginning of m.25 (Example 9) and this could be colored with breath noise in place of a tongued accent. Alternatively, the clarinetist could attempt an imitation of a typical HA-RA-RO[7] gesture, by beginning with a meri head position to approach the note from below, then adding a pulse of air as a re-articulation (Audio Example 4).

Audio Example 4- Ha-ra-ro

Phrase endings in the shakuhachi repertoire are also approached with much care as releasing the sound involves the aesthetic of ma and the transition from breath to breath. We will offer suggestions on a few phrase endings that can be applied throughout Mandat’s movement: 1) The bend at the end of m.2 (see Example 1) imitates the o-ru phrase-ending technique of the shakuhachi. The bend should occur only at the very end of the note and is produced with a quick fall of the head as the breath is stopped. The air should be light, without any forcing of the tone. 2) Mandat notates staccato on the final note of m.4 (see Example 1). This should also be treated as a light release of the breath as the pitch is reached following the bend. There is no need to linger on the final pitch. 3) The release in m.11 (Example 5) is similar but involves a fingering change. Thus the clarinetist must beware not to create any sense of accent with the fingers. The release should be very light in execution, with a lessening of air as the fingers briefly touch the chalumeau B3. 4) The niente in m.24 should be kept very simple, without vibrato or any noise from releasing the fingers. End the phrase with the breath.

Vibrato

In shakuhachi practice, there are several types of vibrato, called yuri, and they are all done through movement of the head rather than diaphragm or throat manipulation of the airstream (as is done is Western flute practice). Therefore, to achieve a closer imitation of yuri on the clarinet joint, we recommend learning the shakuhachi style of vibrato production rather than relying on the more familiar Western style (Audio Example 5).

Audio Example 5- Yuri vibrato

To produce this type of head movement vibrato make sure there is minimal lip or chin pressure against the instrument. Begin by moving the head up and down after the onset of the note. There will be a limited range of playability but there will likely be immediate results. This type of vertical yuri produces extremes in pitch, but because this extreme result is often undesirable, it is sparsely used in traditional playing. Next, sound a note and then move the head side to side as if shaking your head to indicate “no.” Keep the head movements smooth as you move in a limited range, perhaps one inch or less per side. Keep the instrument still. It is your head, not the clarinet, that moves. With this technique it is often very difficult for beginners to get clear yuri on the shakuhachi without several months or more of practice. However, once mastered, this side-to-side technique is both more forgiving and musically flexible than an up-and-down motion. Yuri is most commonly produced in this way.

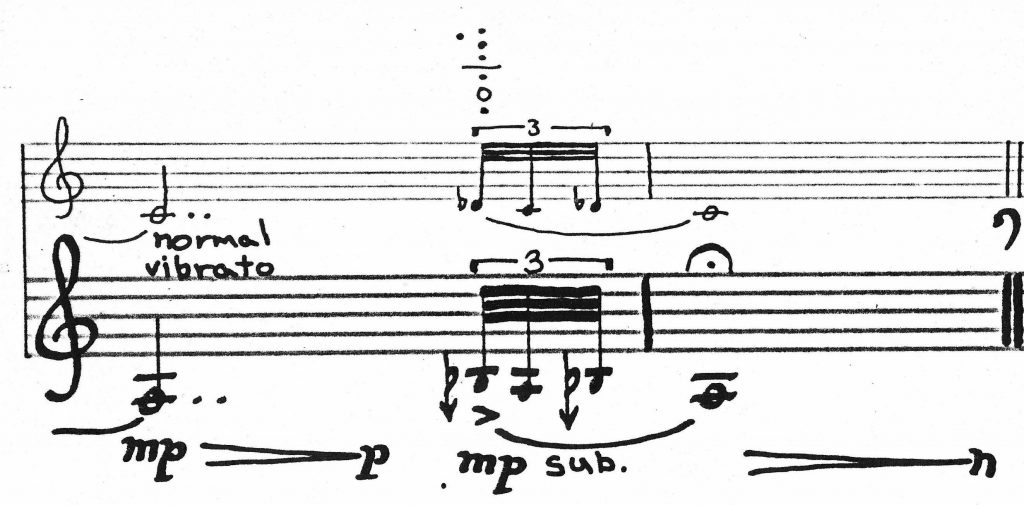

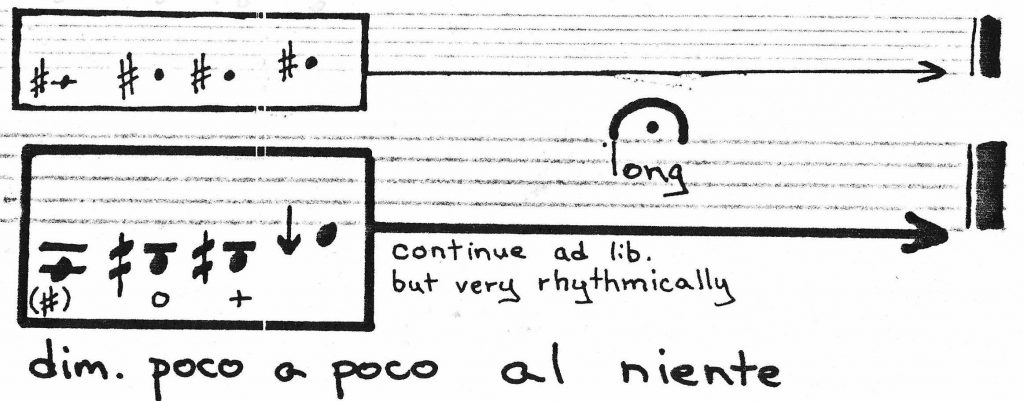

In addition to these two types of yuri there are also techniques where the head movement is more circular with clockwise or counterclockwise motion. Think of these as a path for your head movement and try it, varying the direction between clockwise and counterclockwise, and then changing the plane of the oval, first tilting it diagonally in one direction and then another. There are four types of yuri on the diagonal in traditional playing and they are indicated with symbols and calligraphy lines in the notation. Example 13 shows two examples of graphically notated yuri from a calligraphy score by Yokuyama Katsuya of the anonymous shakuhachi piece Tsuru no sugomori. These excerpts show two types of yuri. On the left, the vibrato begins slowly with a wide horizontal motion that results in a wide pitch range; it gradually narrows as it speeds up. On the right, the yuri is produced with a circular head motion. As with meri technique, a diagonal approach to yuri seems to work most effectively on the clarinet joint.

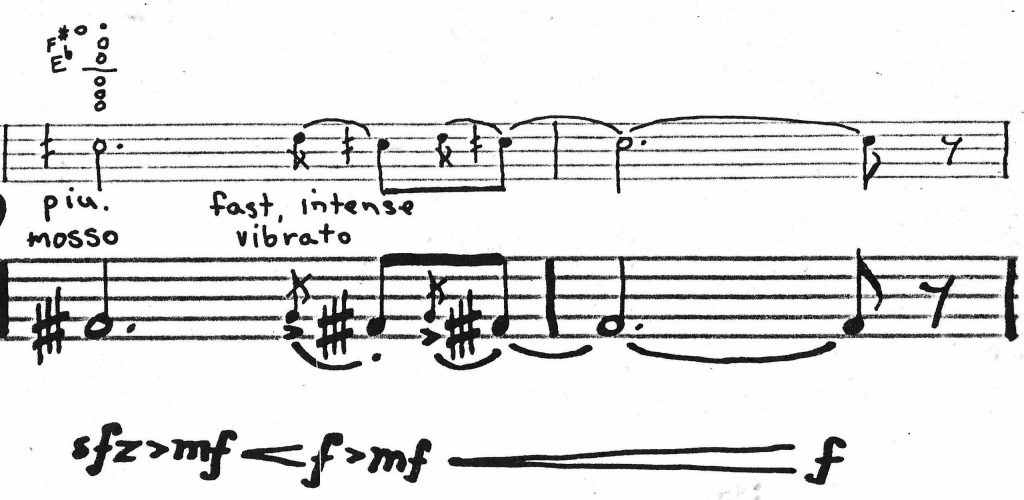

Mandat indicates throughout the movement where vibrato is appropriate and includes guidance on the speed of the vibrato (“fast, intense,” “normal,” or “slow”). We recommend that the clarinetist also take care to shape each instance of vibrato. A constant, unchanging undulation is uncharacteristic in traditional shakuhachi performance. Yuri can be quite complex; however, using head movement to gradually speed up and narrow the bending of the pitch can produce a sensitive imitation. Listening to recordings of the instrument with an ear focused on the varieties of vibrato will also be instructive.

The only instance in Mandat’s Folk Songs movement where we would suggest omitting the vibrato is m.4 (see Example 1). Pitch bending and vibrato are not typically performed simultaneously in traditional shakuhachi repertoire. The bending will be more effective here without an attempt at vibrato.

Bending the single tone

Performance practice of traditional shakuhachi repertoire involves a rich vocabulary of embellishing gestures, a significant portion of which are pitch bends and slides. In both meditative (honkyoku) and Japanese classical (sankyoku) traditional shakuhachi playing, it is seldom desirable to proceed directly from one notated pitch to another. Instead, there are a variety of ways to take “the scenic route” or “the long way around.” For instance, in a very typical gesture proceeding from TSU-meri to RE (E♭ to G), it is common to sound the first pitch then immediately lower it to TSU-dai-meri (E♭-40 cents), bend upward towards G, but stopping along the way at TSU (F) for ornamentation (atari) and finally bending upward to RE (G) (Audio Example 6). In going from an upper pitch to a lower one, it is common to proceed upward from the first pitch before attaining the final, lower pitch. This is achieved through a sliding of the pitch, or suri (e.g., RI to CHI sounds RI suri CHI).

Audio Example 6- “The long way around”

In practical terms, it is not necessary to involve the fingers in the notated pitch bends in this piece. The bends can be produced entirely by meri-kari head movement. For example, in m.4 (Example 1), the entire figure after the grace notes can be done on the open G4 fingering. Using the F♯4 fingering at the low end of the bend risks adding a bump to the sound as two tone holes are closed simultaneously. If the finger had direct contact with a single hole, part-holing could be added, but the bend is achievable here with head movement alone. As with vibrato, diagonal movement on the clarinet joint is quite effective. This measure imitates what is referred to as nayashi in shakuhachi terminology, where the player begins a semitone to a whole tone below the standard written pitch, then bends the pitch upward, cresting at the precise standard pitch level. Nayashi bends are performed primarily by proceeding from meri to kari blowing positions, without major alterations in fingering (Audio Example 7).

Audio Example 7- Nayashi bends

Fingering the mid-bend note is likewise unnecessary on the rising bend in mm.20-21, where there is the risk of unwanted key noise (See Example 7). In m.27, the final notated pitch of the measure anticipates the repeated figure that follows in m.28 (See Example 10). This landing note to the falling bend on fingered G4 also need not be fingered; it will more easily match the style of the next measure without the interference of keywork. A suri upward slide could also be added for color in m.5 (Example 3) between the grace note and the main pitch on beat 2.

Special effects & patterns

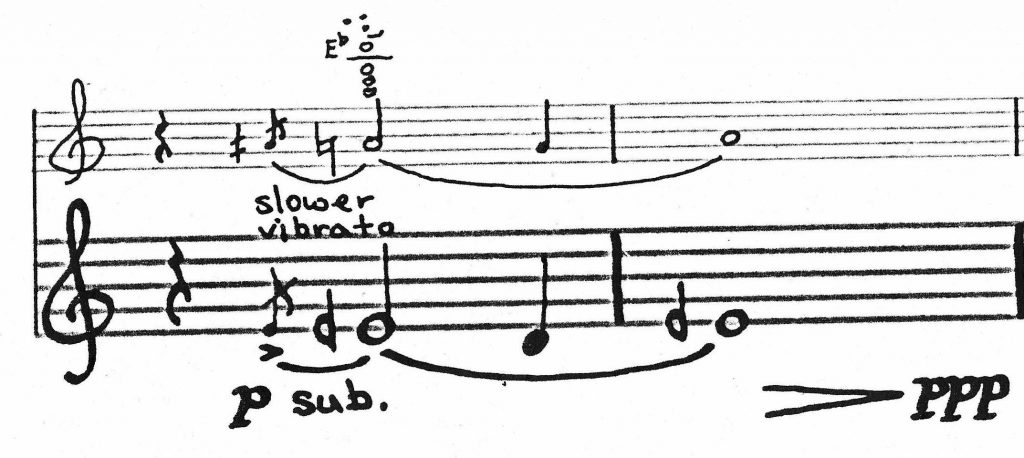

The shakuhachi has traditionally made use of performance techniques that would be considered “extended” in Western classical performance. These techniques are often used for programmatic effect, as is the case with a multiphonic tremolo technique called koro-koro heard in Tsuru no sugomori, a piece that depicts the life cycle of a family of nesting cranes (Audio Example 8). Although the clarinet is not able to directly reproduce this shakuhachi-specific technique, Mandat seems to have found a way to imitate it in his Folk Songs movement. The imitation appears in mm.10, 12, 13, and 16 as a timbral effect (See Example 5). We suggest considering a meri head position for this technique, as would be done on shakuhachi. It does alter the pitch of the gesture but contributes an attractive shakuhachi-like change in timbre and character. This gesture should be practiced slowly so that a distinct interval is heard between the open and closed fingerings when it is executed at tempo.

Audio Example 8- Koro-koro tremolo effect

Conclusion

Studying this piece illustrates just how challenging it can be to move the aesthetic of one cultural system, in this case Japanese Zen Buddhist, into an imitative piece for an instrument and musician of a different cultural system. A sensitive and respectful imitation is nonetheless achievable. As outlined above, we suggest the clarinetist explore timbral subtleties on the sustained tones both within and away from Mandat’s Folk Songs movement. Also beware of micromanaging—each technique or sound should flow from one to the next.

We highly recommend that anyone tackling this piece play the movement for a shakuhachi player. There are some masters in North America who teach online if none are accessible in person. And finally, we suggest listening to the great shakuhachi masters playing the traditional repertoire. Recordings by Yamaguchi Goro, Aoki Reibo, Yokoyama Katsuya, and Kurahashi Yoshio are easy to find. Pieces that would be instructive for capturing this particular imitation on clarinet include Tamuke and Tsuru no sugomori.

Musical Examples

Example 1 (mm.1-4)

Example 2, mm.1-2 with atari added to first note

Example 3, mm.5-6

Example 4, mm.7-9

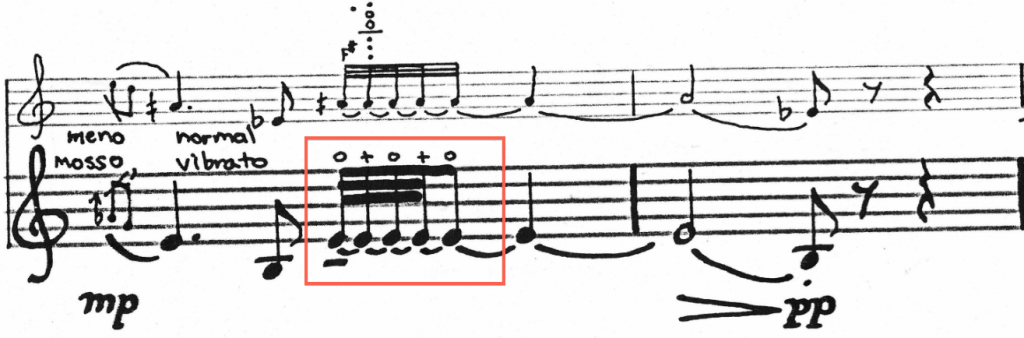

Example 5, mm.10-11. Boxed gesture is imitation of koro-koro technique

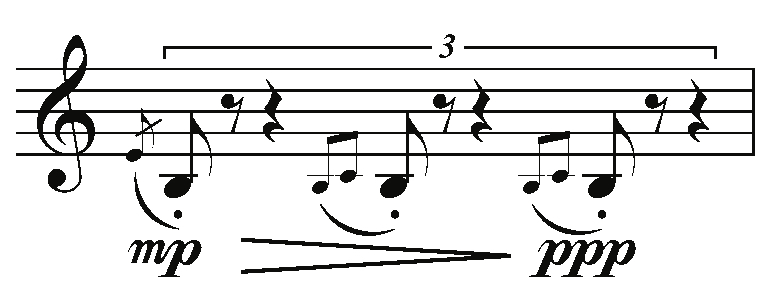

Example 6, m.15 with atari notes added

Example 7, mm.20-22

Example 8, mm.23-24

Example 9, mm.25-26

Example 10, mm.27-28

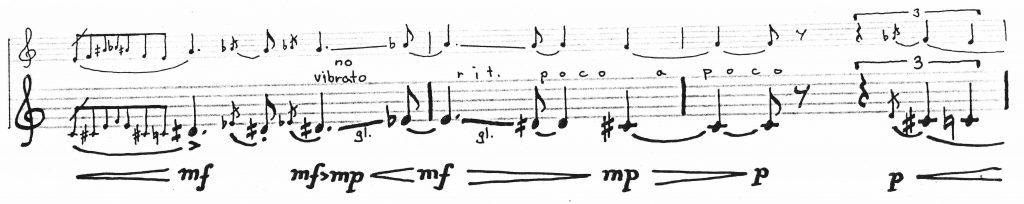

Example 11, mm.33-34. Atari could be added to boxed notes

Example 12, m.36

Example 13, Graphic notation of yuri vibrato in Tsuru no sugomori. Calligraphy by Yokuyama Katsuya

[1] Japanese names are presented with surname first.

[2] Zachary Wallmark, “Sacred Abjection in Zen Shakuhachi,” Ethnomusicology Review 17 (2012): 5.

[3] Matsunobu Koji, “Japanese Spirituality and Music Practice: Art as Self-cultivation,” in International Handbook of Research in Arts Education, ed. Liora Bresler (Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer, 2007), 1428.

[4] Takemitsu Tōru, Confronting Silence, trans. Yoshiko Kadudo and Glenn Glasow (Berkeley: Fallen Leaf Press, 1995), 51.

[5] Riley Kelly Lee, “Yearning for the Bell: A Study of Transmission in the Shakuhachi Honkyoku Tradition” (Ph.D. diss., University of Sydney, 1993), 266.

[6] Ibid., 355.

[7] Capitalized syllables refer to shakuhachi fingerings and head positions.

About the Authors

Amy Simon has a PhD in ethnomusicology from York University in Toronto and an MMus in clarinet performance from the University of Victoria, BC. She toured internationally for several years as an orchestral clarinetist with Shen Yun Performing Arts and has taught musicology at the University of Prince Edward Island. She is a student of the Japanese shakuhachi.

Dr. Gerard Yun is Assistant Professor of Community Music at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario. He is also shakuhachi instructor at York University in Toronto and maintains a private shakuhachi studio. Dr. Yun performs traditional honkyoku in solo recitals and regularly appears in cross-cultural and fusion performances. He studies shakuhachi with master teachers Michael Chikuzen Gould (dokyoku), David Kansuke Wheeler (sankyoku), and Yodo Kurahashi II (meian).

Comments are closed.