Audio Reviews: February 2020

Michael Finnissy: Six Sexy Minuets Three Trios and Other Works. Kreutzer Quartet: Peter Sheppard Skærved, violin; Mihailo Trandafilovski, violin; Clifton Harrison, viola; Neil Heyde, cello; Linda Merrick, clarinet. Michael Finnissy: Civilisation; Contrapunctus XIX; Clarinetten-Liederkreis; Mad Men in the Sand; Six Sexy Minuets Three Trios. Métier Records, MSV 28581. Total Time: 68:21.

Michael Finnissy: Six Sexy Minuets Three Trios and Other Works. Kreutzer Quartet: Peter Sheppard Skærved, violin; Mihailo Trandafilovski, violin; Clifton Harrison, viola; Neil Heyde, cello; Linda Merrick, clarinet. Michael Finnissy: Civilisation; Contrapunctus XIX; Clarinetten-Liederkreis; Mad Men in the Sand; Six Sexy Minuets Three Trios. Métier Records, MSV 28581. Total Time: 68:21.

Métier’s 2018 disc Michael Finnissy: Six Sexy Minuets Three Trios and Other Works represents a communion of three closely-associated British coconspirators: the renowned, maverick composer Michael Finnissy; the U.K.-based Kreutzer Quartet, dedicatee of two of the composer’s quartets and consistent champion of his other works; and clarinetist Linda Merrick, Principal of the Royal Northern College of Music. This 13th release in Métier’s series of Michael Finnissy recordings largely consists of the composer’s music for string quartet, with Merrick spotlighted on the five-movement Clarinetten-Liederkreis.

Finnissy’s music can be challenging, but the disc gets off to a promising start with the opening tracks of Civilisation, an interrogation of what it actually means to be civilized, delivered in immediate, vivid language by Finnissy and realized with arresting commitment by the Kreutzer Quartet. Contrapunctus XIX follows, Finnissy’s striking and compelling extrapolation of a quadruple fugue left unfinished by Bach in his landmark volume The Art of the Fugue, BWV 1080.

The Clarinetten-Liederkreis that comes next turns out to be an overall convincing work; the Schumann reference of its title, less so. Indeed, the choice of string quartet to fill out the self-advertised “clarinet song cycle” seems unexpected compared to the more obvious choice of piano (as in Schumann’s own Liederkreis, Op. 39), but not invalid. More puzzling, though, is the conspicuous absence of song from the piece. The way the voices stir one by one in the first movement’s delicate opening and then proceed with cool indifference toward one another calls to mind the calculated counterpoint of Hindemith before Schumann — more in line with the preceding Contrapunctus than the promised song cycle. The independent parts do occasionally coalesce into lush textures, and Merrick and the Kreutzer Quartet find a robust blend that makes those moments all the more rewarding. I regret that I found myself looking to Schumann to excuse the less convincing aspects of the composition, as if the movement’s lack of direction and unceremonious ending could be oblique references to the circularity and understatedness of Schumann’s music. Perhaps those qualities prove more effective in Schumann precisely because of the songlike writing that guides them, but is missing here.

The impassioned writing of the pained Largo appassionato movement proves effective and gripping, if a little too fraught for Schumann, whose expressivity tends to lie in what is left unsaid, rather than what is present. Nevertheless, the palpable distance between the agitated string writing far beneath the altissimo-bound clarinet makes for a powerful movement. For her part, Merrick shapes her stratospheric sighs with the shimmer of a bowed vibraphone, rendering the compelling effect of a halo high above the anguished strings.

The third movement’s klezmer-inflected solo clarinet soliloquy finally acknowledges the connection to the voice suggested by the work’s title, but I would hesitate to call it song; rather, the improvisatory character, the stutter of repeated notes and gestures, and the religious solemnity approach something like a mystic incantation. Whatever her imagined character, Merrick inhabits it expertly and transports the listener to “fremden Ländern”, to borrow from Herr Schumann.

The rambunctious, stomping fourth movement bastardizes the “Eastern” sound world conjured by the preceding movement with a sort of drunken parade reminiscent of Khachaturian-style folk dances. The ensemble demonstrates unrelenting commitment to that rollicking character, and I especially enjoyed the obnoxious hurdy-gurdy drones (or are they car horns?) of the upper strings.

To my ears, the eerie final movement seems more like a promising beginning than the culmination of what we’ve heard so far. It is effective writing, however, with the nasty rub of overlapping voices sounding something like electronic feedback drawing ever nearer.

– Graeme Steele Johnson

One at a Time: Solo Instrumental Music by Douglas Anderson. Maureen Keenan, flute; Jill Collura, bassoon; Jin-ok Lee, piano; Debbie Schmidt, French horn; Gary Dranch, clarinet; Ina Litera, viola; John Charles Thomas, trumpet and flugelhorn; Richard Cohen, bass clarinet. Douglas Anderson: “…increasingly, physical…”; “…procession, emerging…”; Five Bagatelles and a Synopsis; “…springing, gradually…”; Piece for Clarinet and Tape; “…mood, enough…”; Wedding Music; “…vikings, unless…”; Abe’s Rag. Ravello Records, RR7992. Total Time: 64:57.

One at a Time: Solo Instrumental Music by Douglas Anderson. Maureen Keenan, flute; Jill Collura, bassoon; Jin-ok Lee, piano; Debbie Schmidt, French horn; Gary Dranch, clarinet; Ina Litera, viola; John Charles Thomas, trumpet and flugelhorn; Richard Cohen, bass clarinet. Douglas Anderson: “…increasingly, physical…”; “…procession, emerging…”; Five Bagatelles and a Synopsis; “…springing, gradually…”; Piece for Clarinet and Tape; “…mood, enough…”; Wedding Music; “…vikings, unless…”; Abe’s Rag. Ravello Records, RR7992. Total Time: 64:57.

New York-based composer-conductor Douglas Anderson’s career is put on display in microcosm in Ravello Records’ 2018 release One at a Time: Solo Music by Douglas Anderson. The disc highlights Anderson’s music for a variety of single instruments composed over nearly 40 years, and this retrospective compendium allows listeners to trace the development of the composer’s style through these perennial touchstones of his solo instrumental works. The collection’s two pieces for clarinets hold an especially summative significance for this album, as they chronologically bookend the rest of the works on the CD: Piece for Clarinet & Tape, from 1975, is the oldest of the volume, and the 2011 “…vikings, unless…” for solo bass clarinet is the most recent.

To modern ears, the delightfully primitive electronic sounds of Piece for Clarinet & Tape betray its age, but the Pac-Man-esque beeps and blips of the tape (even that word is anachronistic now) perfectly capture the zeitgeist of the nascent computer era, with all of its possibility, mystery and vague sense of anxiety. The tape also has a fascinating way of constructing a sense of physical space within the piece, as its vanishing echoes seem to map out some sort of vacant chasm. Within this unfeeling void, the clarinet’s melancholy crooning seems to give voice to the emptiness of infinity. The crooner here is clarinetist Gary Dranch, who weaves seamlessly in and out of the tape, sometimes coloring it from within and other times leading the textural changes himself, but most dazzlingly by nimbly flitting through acrobatic maneuvers that cause us to lose track of what is live and what is pre-recorded. Dranch’s malleable tone artfully serves his musical shapeshifting.

The admittedly ambiguous title of “…vikings, unless…” seems to offer dual impressions: the Viking context, for one, as well as a kind of self-conscious doubt expressed by the word “unless…” The Viking imagery seems clear enough at the opening, where the declamatory repetition of simple intervals evokes a Viking-style Gjallarhorn. But this initial pride soon gives way to conflict in the form of unrelenting staccato that dips and dives across extremes of the bass clarinet’s range, threatening the security of the beginning Viking image. The triumphant horn call does return near the end of the piece, but something about the ominous shading of the bass clarinet’s final notes seems to cast doubt on the Viking heroism that had ostensibly prevailed. It is as if the piece ends by musing, “unless…” The work is altogether thoroughly engaging, and Anderson’s intimation — without explicit articulation — of such sophisticated narrative elements with such limited musical materials is commendable. Bass clarinetist Richard Cohen navigates this surely taxing piece with impressive facility and character.

– Graeme Steele Johnson

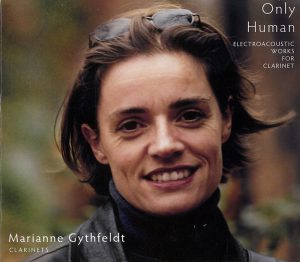

Only Human: Electroacoustic Works for Clarinet. Marianne Gythfeldt, clarinet, bass clarinet; John Link, electronics; Mikel Kuehn, electronics; David Taddie, electronics; Elizabeth Hoffman, electronics; Eric Lyon, electronics; Robert Morris, electronics. John Link: Only Human; Mikel Kuehn: Rite of Passage (Hyperresonance V); David Taddie: Licorice Stick Groove; Elizabeth Hoffman: And when white moths were on the wing; Eric Lyon: Little History of Photography; Robert Morris: On the Go. New Focus Recordings, fcr220. Total Time: 66:50.

Only Human: Electroacoustic Works for Clarinet. Marianne Gythfeldt, clarinet, bass clarinet; John Link, electronics; Mikel Kuehn, electronics; David Taddie, electronics; Elizabeth Hoffman, electronics; Eric Lyon, electronics; Robert Morris, electronics. John Link: Only Human; Mikel Kuehn: Rite of Passage (Hyperresonance V); David Taddie: Licorice Stick Groove; Elizabeth Hoffman: And when white moths were on the wing; Eric Lyon: Little History of Photography; Robert Morris: On the Go. New Focus Recordings, fcr220. Total Time: 66:50.

John Link’s Only Human (2005) begins with an ethereal sense of tension that descends into electronic bop reminiscent of a fractured New York Counterpoint. The harmonies slide around and collide with a hesitant melody and yodeling trills that build in uneasy waves to the stratosphere before ebbing away. Gythfeldt proves capable of gentle soulful lines and harsh cries showing great flexibility.

Mikel Kuehn’s Rite of Passage (2014) crashes through frenetic key clicks and bass clarinet outbursts in search of new sounds using hyper resonance and impressive spatters of articulation. A sound world of air, clicks and tone provides a foil to passages of dialogue between bass clarinet and playback that comment playfully on Stravinsky’s passages for bass clarinet in Rite of Spring.

Licorice Stick Groove (2018) by David Taddie allows the listener to explore a world of digitized sounds guided by Gythfeldt’s intrepid solo lines, seeming to relax into a syncopated jam session in the middle that pays homage to Benny Goodman with playfulness that is nothing less than virtuosic and despairing followed by a respite, double-tonguing and a wild recapitulation of the jam session.

And when white moths were on the wing… (2015) speaks to us from the other side of an electronic divide featuring more daring composite sounds and character depictions by the clarinet that imitate fluttering wings of gargantuan size and simple folk-like melodies with a tribal sonority before settling into plaintive downward lines, slap tongue and warbles. The longevity of the collaboration between Marianne and composer Elizabeth Hoffman is evident in the seamless adaptations between the live electronics and the performer.

Little History of Photography (2017), written for clarinet and interactive computer, indulges in manipulations of the melodic lines, which are relentless for the most part, including brief cadenzas as it traverses various digitalized landscapes, alternating between dreamy and lugubrious. Occasionally, the manipulations seem to suspend certain moments in zero gravity but Gythfeldt is brilliant in the twisting lines of this virtuosic piece.

Robert Morris’ On The Go (1999) returns to the more traditional form of a concerto with electroacoustic accompaniment and ongoing dialogue between the two. It is a circular argument as it is the oldest piece on the album, reminding us of how far we have come in twenty years and what it means to be human with the technology available to us today.

– Andrea Vos-Rochefort

3: The Music of Gina Biver. Fuse Ensemble: Greg Hiser, violin; Ina Mirtcheva Blevins, piano; Gina Biver, spoken word, electric guitar; Colette Inez, spoken word; Jennifer Lapple, flute; Ethan Foote, bass; Scott Deal found percussion, marimba, triggered audio; Pam Clem, cello; Angela Murakami, clarinet. Gina Biver: Mirror; Girl, Walking; We Meet Ourselves; The Cellar Door; No Matter Where. Ravello Records, RR7993. Total Time: 44:23.

3: The Music of Gina Biver. Fuse Ensemble: Greg Hiser, violin; Ina Mirtcheva Blevins, piano; Gina Biver, spoken word, electric guitar; Colette Inez, spoken word; Jennifer Lapple, flute; Ethan Foote, bass; Scott Deal found percussion, marimba, triggered audio; Pam Clem, cello; Angela Murakami, clarinet. Gina Biver: Mirror; Girl, Walking; We Meet Ourselves; The Cellar Door; No Matter Where. Ravello Records, RR7993. Total Time: 44:23.

3 is a collaboration between Gina Biver and Fuse Ensemble with a lovely comfortable feel. Found sounds interspersed with simple piano chords, thin violin contributions and hesitant clarinet interjections create a chill vibe for No Matter Where (2010). The piano represents words from Kerouac’s On The Road translated into notes, chords and ascending lines taken from Indian raga that are imprinted on to the violin and clarinet. The busy nature of these lines is seemingly more violin-friendly but the exchange provides welcome dialogue and contrasts before fading away in a final section of prepared piano and plucked violin. The album as a whole presents interesting questions about the transferring of spoken words to musical sounds and vice versa creating a musical world peopled with poetry.

– Andrea Vos-Rochefort

Whispering Fragrance: The Chamber Works of Stephen Yip. Henry Chen, double bass; Yu-Chen Wang, guzheng; Yu-Fang Chen, violin; Daniel Gelok, saxophone; Rudy Michael Albach, double bass; Andrew Schneider, piano; Jiuan-Reng Yeh, guzheng; Izumi Miyahara, flute; Masahito Sugihara, saxophone; Ben Roidl-Ward, bassoon; Thelema Trio: Rik De Geyter, clarinet; Peter Verdonck, saxophone; Ward De Vleeschhouwer, piano. Stephen Yip: Ding; Whispering Fragrance; In Seventh Heaven; Ran; Tranquility in Consonance; Peace of Mind. Navona Records, NV6175. Total Time: 66:54.

Whispering Fragrance: The Chamber Works of Stephen Yip. Henry Chen, double bass; Yu-Chen Wang, guzheng; Yu-Fang Chen, violin; Daniel Gelok, saxophone; Rudy Michael Albach, double bass; Andrew Schneider, piano; Jiuan-Reng Yeh, guzheng; Izumi Miyahara, flute; Masahito Sugihara, saxophone; Ben Roidl-Ward, bassoon; Thelema Trio: Rik De Geyter, clarinet; Peter Verdonck, saxophone; Ward De Vleeschhouwer, piano. Stephen Yip: Ding; Whispering Fragrance; In Seventh Heaven; Ran; Tranquility in Consonance; Peace of Mind. Navona Records, NV6175. Total Time: 66:54.

The intriguing chamber works of composer Stephen Yip can be heard on his new album, Whispering Fragrance. Yip was born in Hong Kong but now resides in the United States. This duality of home can be heard in his music’s unique ability to blend modern western techniques with a distinctly eastern color pallet.

There is only one composition on the album featuring clarinet. It is the final work, Peace of Mind, written for bass clarinet, baritone saxophone and piano, and performed masterfully by the Belgian ensemble, Thelema Trio. It opens with very percussive sounds in the bass clarinet and piano before developing into some fascinating extended technique work in all instruments. The frequent shifting between atmospheric note bends, percussive rhythms, jazz chords in the piano and numerous mood changes, keeps the work engaging for its full 12 minutes.

Although Peace of Mind is the only work that includes clarinet, the entire album is enlightening and worth exploring. There are two works featuring a type of ancient Chinese zither called a guzheng. Furthermore, woodwind enthusiasts may enjoy In Seventh Heaven, written for saxophone, double bass, and piano. This piece is an interesting representation of Chinese tonality, but is also strongly reminiscent of American-style jazz combo. In a similar vein is Tranquility with Consonance for flute, saxophone, bassoon and piano. In this work, the woodwinds are tasked with some impressive extended techniques, but still play in a style very reminiscent of nature and Chinese culture. Yip said that he asked the musicians to find the most natural sound of their instrument and explore “their own original or primitive manner.” This connection to nature and culture can be heard throughout the album, and make it very enjoyable.

– Madelyn Moore

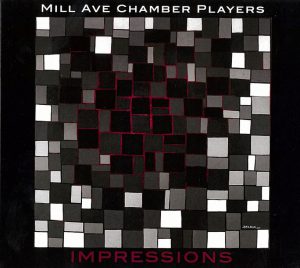

Impressions. Mill Ave Chamber Players: Monica Sauer Anthony, flute; Nikolaus Flickinger, oboe; Katherine Palmer, clarinet; Thomas Breadon, bassoon; Rose French, horn. Kerry Turner: The Road To Tasartico; Thomas Breadon, Jr: Impressions; Robert V. Springer: Intersections; Jessica Meyer: If Only I; John Steinmetz: What’s Going On. Independent Release. Total Time: 51:02.

Impressions. Mill Ave Chamber Players: Monica Sauer Anthony, flute; Nikolaus Flickinger, oboe; Katherine Palmer, clarinet; Thomas Breadon, bassoon; Rose French, horn. Kerry Turner: The Road To Tasartico; Thomas Breadon, Jr: Impressions; Robert V. Springer: Intersections; Jessica Meyer: If Only I; John Steinmetz: What’s Going On. Independent Release. Total Time: 51:02.

Impressions is the latest album from the Mill Ave Chamber Players, a woodwind quintet hailing from Phoenix, Arizona. It is a diverse collection of contemporary woodwind quintet music and the ensemble performs these works expertly.

The first piece on the album, The Road to Tesartico by Kerry Turner, features the lovely tone of Katherine Palmer on both clarinet and bass clarinet, and gives the listener the impression of a group that is uncertain or nervous at the beginning of a journey, travels down a bumpy road with beautiful vistas in the distance, and finally comes to a peaceful rest at their destination.

Next on the album is Thomas Breadon’s Impressions. This five-movement work is thoroughly compelling from start to finish and is performed sensitively and skillfully by the Mill Ave Chamber Players. This work proves that Breadon has a gift for arousing moods and creating scenes for his listener. Throughout the work, all instruments display their technique and ability to communicate with one another. Most notably, there are some beautiful moments for the horn in the first and second movements, sensitive use of flute and clarinet extended techniques in the third movement, and a beautiful oboe solo by Nikolaus Flickinger in the final movement.

If Only by Jessica Meyer opens with another lovely oboe solo that passes around the ensemble before climaxing in a high, heart-wrenching melody that, as one might expect from the title of the piece, never really resolves.

What’s Going On is the final composition on the album. It was written by John Steinmetz, who also produced the recording. This work is four movements and employs several interesting compositional techniques. The first and third movement sound almost improvisatory while the use of wide harmonies in the second movement is reminiscent of folk music.

Overall, Impressions is a compelling album featuring excellent musicianship both from the Mill Ave Chamber Players and the composers who contributed works.

– Madelyn Moore

Comments are closed.