Originally published in The Clarinet 52/3 (June 2025).

Copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

A WORK FOR A VIRTUOSO: Percy Pitt’s Concertino in C minor

In 1894 the Queen’s Hall Orchestra was founded in London, with the illustrious clarinetist Manuel Gómez as the orchestra’s first clarinet. In the 1897 season of the Proms Concerts, Gómez had the opportunity to perform as a soloist. For the occasion, a work was commissioned from the composer Percy Pitt (1869-1932).

by Pedro Rubio

Lea la versión en español de este artículo aquí: Una obra para un virtuoso: el Concertino en do menor de Percy Pitt (Versión en Español)

A definite step in English clarinet-playing is marked by the arrival in London of Manuel Gomez in the late 1880s. […] The influence of Gomez on the younger school of players was great. It may be said that he introduced the Boehm system to England. And further, he provided a stimulus. … In spite of the efforts of Lazarus and Clinton, interest in the clarinet as a solo instrument had been declining. Gomez did much to restore it by inducing musicians to compose for it.

– F. Geoffrey Rendall,

The Clarinet1

This quotation began the article I wrote about the clarinetist Manuel Gómez in The Clarinet 46 no. 3 (June 2019). And it may well serve again for this essay, since one of the pieces to which Rendall referred was undoubtedly Percy Pitt’s Concertino, op. 22, in C minor. Among all the pieces composed for Gómez, the Concertino is the work of greatest magnitude and most demanding virtuosity, but not without notable musical interest. A thorough study of the score reveals a composer with solid training and personal inspiration who controls his compositional and formal tools at all times. It is also evident that he knew well the instrument for which he was writing and the clarinetist who was going to perform his music.

This article will examine some biographical information on the composer and the clarinetist who was the dedicatee of the work, along with some notes on the historical context in which the Concertino was composed, and its main structural and musical characteristics. I will also present a new edition of the score that we hope will serve to recover one of the most interesting and least known English composers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

THE COMPOSER

Percival George (Percy) Pitt was an English organist, pianist, conductor, and composer. Born in London, at 18 he went to study at the Leipzig Conservatory with Carl Reinecke (1824-1910), completing his training in Munich and Berlin with the composer and organist Josef Rheinberger (1839-1910). After finishing his studies in 1893, he returned to London where he worked for the Queen’s Hall Orchestra, participating in the first Promenade Concerts held in 1895 under the auspices of Robert Newman (1858-1926) and Henry John Wood (1869-1944). From 1896, Pitt would be the orchestra’s pianist, organist, and celesta player. In 1902 he became assistant director and musical advisor of the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden, and in 1915 he was appointed director of the Beecham Opera Company. In 1920 he would go on to direct the British National Opera Company. Between 1923 and 1930 he was director of the British Broadcasting Company, designated the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) since 1927. As a composer, highlights include his orchestral works, several stage pieces, and compositions intended for great virtuosos, such as the Concertino for clarinet and orchestra, dedicated to Manuel Gómez, and the Ballade for violin and orchestra, for Eugène Ysaÿe (1858-1931).

Figure 1. Percy Pitt, 1917. P. Rubio Archive.

Percy Pitt had a close relationship with the clarinetist brothers Manuel and Francisco Gómez and the community of other Spanish artists who settled in London, like the painter Luis Ricardo Falero (1851-1896), the violinist Enrique Fernández-Arbós (1863-1939), and the cellist Agustín Rubio (1856-1940). His relationship also extended to great figures on the international scene such as Pablo Sarasate (1844-1908) and Isaac Albéniz (1860-1909). About the latter, he wrote:

I really think that Albeniz was one of the most sympathetic and loveable men one could possibly met. I remember, too, that at this particular time he has just finished his second opera, Pepita Jimenez, and one summer evening several of us spent some hours at Francis Coutts’s flat […] whilst Albeniz played us this, his latest opera—a very beautiful and characteristic work.2

Among British composers, Pitt was a fellow student with Frederick Delius (1862-1934) in Leipzig, and a personal friend of Edward Elgar (1857-1934). The relationship between Pitt and Elgar was always close and cordial, as we can see in this letter:3

My dear Elgarmusdock,

Greeting!

I shall have great pleasure in joining yr. friend & you, O Great Pundit, at Abendbrod on Tuesday at seven of the clock altho I may, later, be obliged to go down to the theatre.

Don’t order a brass band.

Yours always.

Percy P.

Percy Pitt has left us numerous examples of his work as a conductor and performer in various recordings made at the beginning of the 20th century. Between 1907 and 1929 he recorded, as conductor or accompanying pianist, no less than 53 musical fragments marketed under the labels Gramophone Monarch Record and Columbia.4

Pitt’s obituary in The Musical Times, in addition to reviewing the achievements he accomplished in life, mentioned his production as a composer: “Thoroughly wholesome, thoroughly sound in material and workmanship as it is, his music has more than that to commend it—poetry and vision and a fine sense of the dramatic.”5

THE DEDICATEE

Manuel Gómez (1859-1922) was born in Seville into a very humble family. He spent his childhood in the San Fernando Begging Asylum, an orphanage in the Andalusian capital. There Manuel began his clarinet studies with Antonio Palatín (1828-1894), director of the institution’s band in those years. Shortly after, Manuel’s younger brother, Francisco Gómez (1866-1932), would join clarinet classes. In 1879, advised by Palatín, the young Manuel went to complete his musical training at the Madrid Conservatory. There in just two years he would complete the six stipulated courses, finishing his studies with the Clarinet Prize in 1881. Given the extraordinary qualities of this clarinetist, Antonio Palatín recommended that Manuel follow in the footsteps of his nephew Fernando and continue his studies at the Paris Conservatory.6 This time the trip was accompanied by his brother Francisco, who had also shown notable qualities on the clarinet. In Paris, the two brothers entered the clarinet class of Cyrille Rose (1830-1902) for the 1882-83 academic year. Manuel finished his studies in 1885 as a laureate of the conservatory, which opened the doors of the Paris Opera Orchestra, an ensemble in which his teacher Rose was a soloist between 1857 and 1891.7

Figure 2. Manuel Gómez. Detail of the photograph “Sir Henry Wood and the soloist of the Promenade Concerts.” William Whiteley Ltd., c. 1899. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

In the summer of 1884, Manuel began to collaborate with English orchestras. These contacts would be decisive in the future of his professional career. Manuel’s reputation as an excellent instrumentalist allowed him to settle in the United Kingdom at the end of 1885, first in Manchester and later in London. Due to the numerous job opportunities that England presented, Francisco Gómez followed in the footsteps of his older brother, becoming over the years one of the most respected basset horn and bass clarinet players. Among all the British orchestras of which Manuel Gómez was the principal clarinetist, most notable are the Royal Italian Opera Orchestra at Covent Garden, the Queen’s Hall Orchestra, and the London Symphony Orchestra. Of the latter, Manuel was a founding member and clarinet soloist until his retirement in 1916.

When the incipient phonograph industry arrived in England at the beginning of the 20th century, Manuel Gómez, thanks to his prestige, was the clarinetist who made the first recordings. As a solo artist, he made three recordings for The Gramophone Co. Two of them are dated 1902-03: “Caro Nome,” from Verdi’s Rigoletto (an excerpt from Luigi Bassi’s well-known Fantasia on the opera motifs) and Chanson Napolitaine by René de Boisdeffre (1838-1906).8 The third recording, released in 1911, was “Non più di Fiori,” the celebrated Mozart aria for mezzo-soprano and basset horn obbligato from La clemenza di Tito.9 Manuel plays the basset horn part with the British singer Louise Kirkby-Lunn (1873-1930).

THE COMMISSION OF PITT’S CONCERTINO AND THE INFLUENCE OF CAVALLINI AND WEBER

When the Queen’s Hall Orchestra was founded in 1894, it quickly became one of the most significant orchestras in the United Kingdom. Since its beginnings, this group maintained intense activity, with milestones including being the first British orchestra to adopt in the islands the “normal” or “continental” tuning pitch (A=435Hz)—in use in the rest of Europe since 1859—and performing a Promenade Concert on August 10, 1895 that was a direct precursor to the famous BBC Proms of today.

Manuel Gómez was the orchestra’s first clarinet since its creation, and in the 1897 season, he had the opportunity to perform as a soloist. For the occasion, a work was commissioned from the composer Percy Pitt. Manuel suggested to Pitt that he use some musical themes Manuel had by the great Italian clarinetist and composer Ernesto Cavallini (1807-1874). According to researcher Charlotte Kennedy: “The sketch he found was basically two or three themes and a few florid passages for clarinet, but without accompaniment of any kind.”10 Where could Manuel obtain that Cavallini material without any accompaniment? In a quick consultation of Pitt’s work, we can verify that these passages belong to the first movement of the Italian composer’s Concerto No. 2 in C minor for clarinet and orchestra (Fig. 3).11

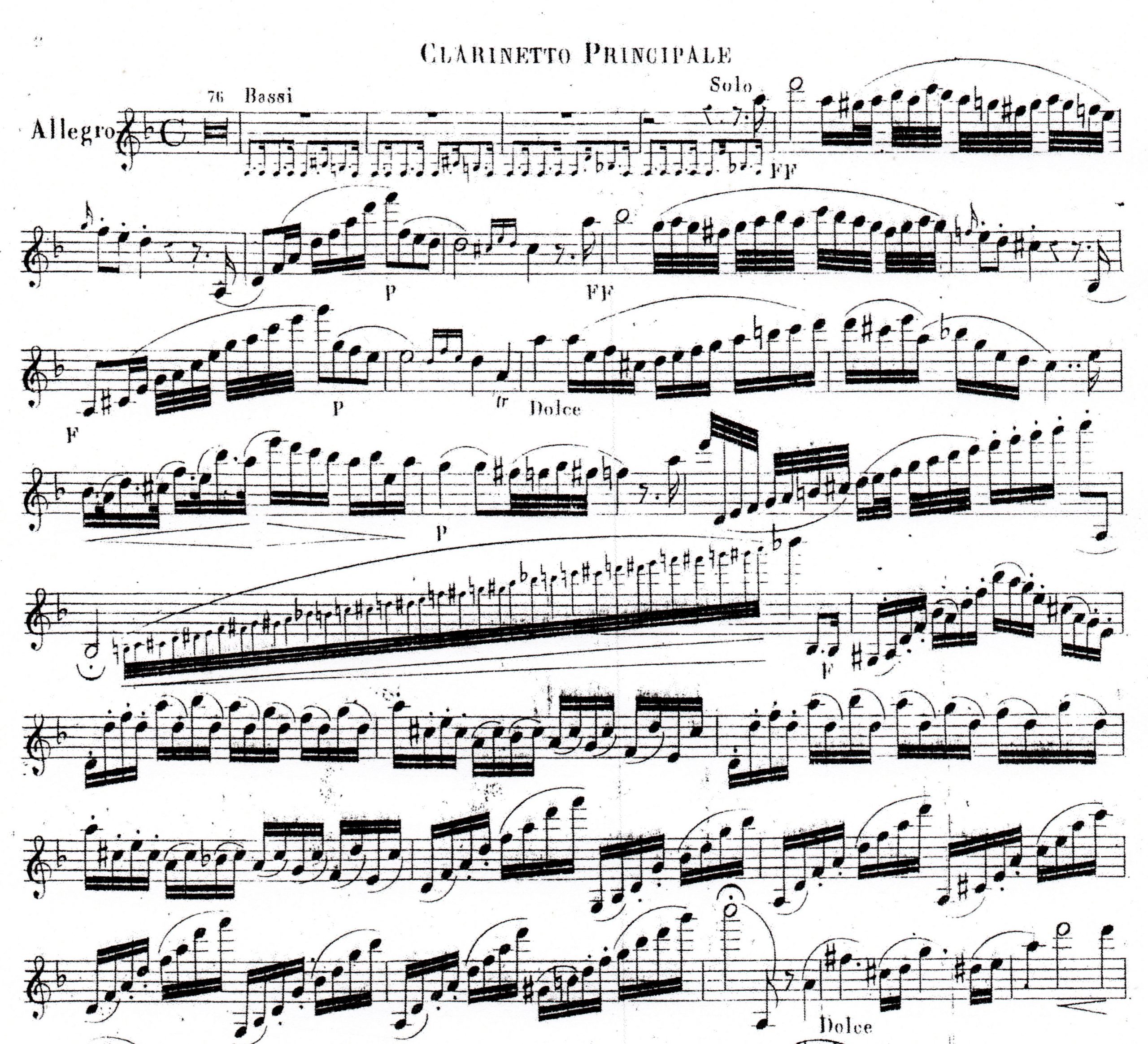

Figure 3. Ernesto Cavallini, Clarinet Concerto No. 2, first movement, clarinet part. First edition, Milan, 1832. L. Magistrelli Archive.

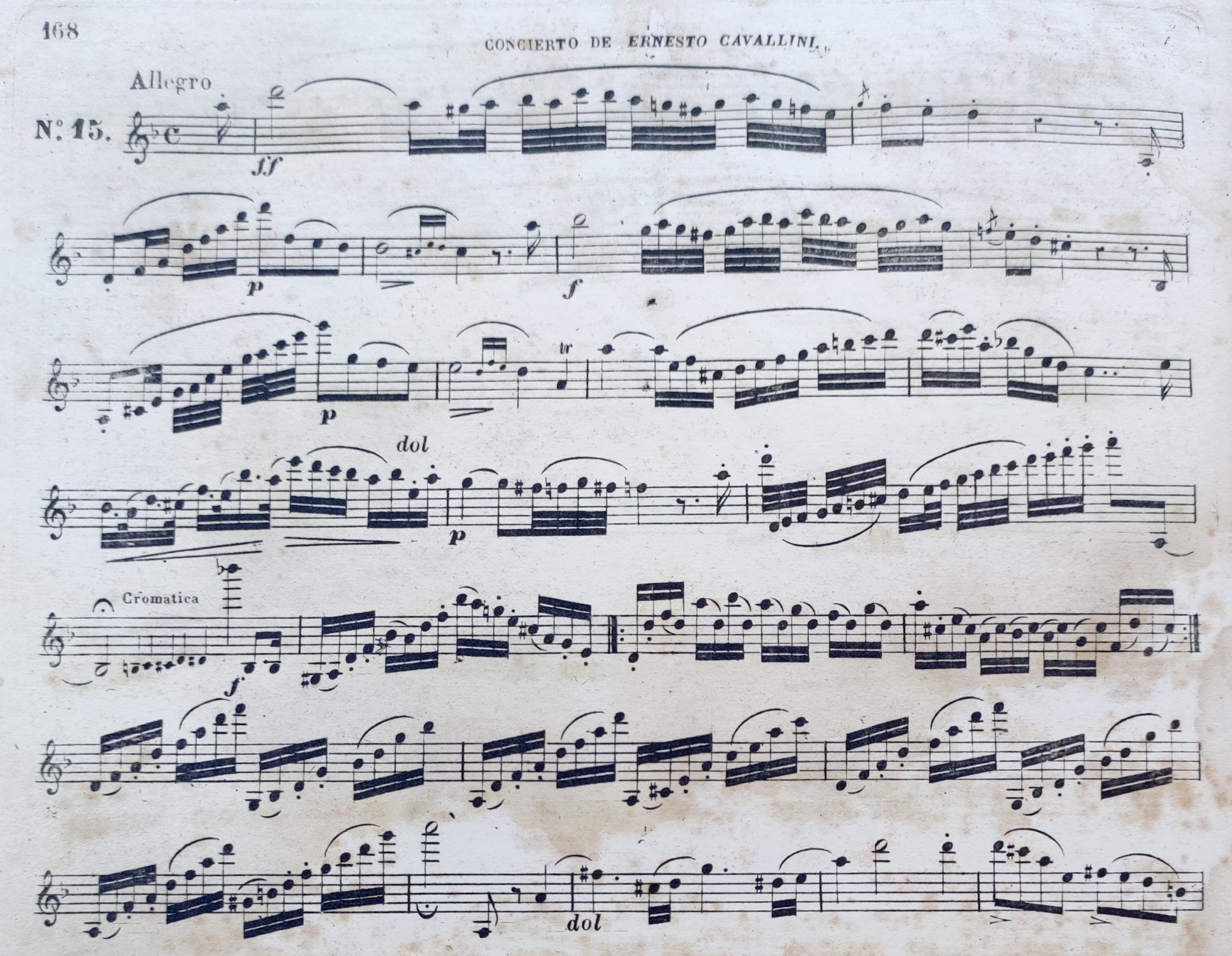

Figure 4. Ernesto Cavallini, Clarinet Concerto No. 2, first movement, clarinet part. Antonio Romero’s Clarinet Method, 2nd edition, pp. 168-169, Madrid, 1860. P. Rubio Archive.

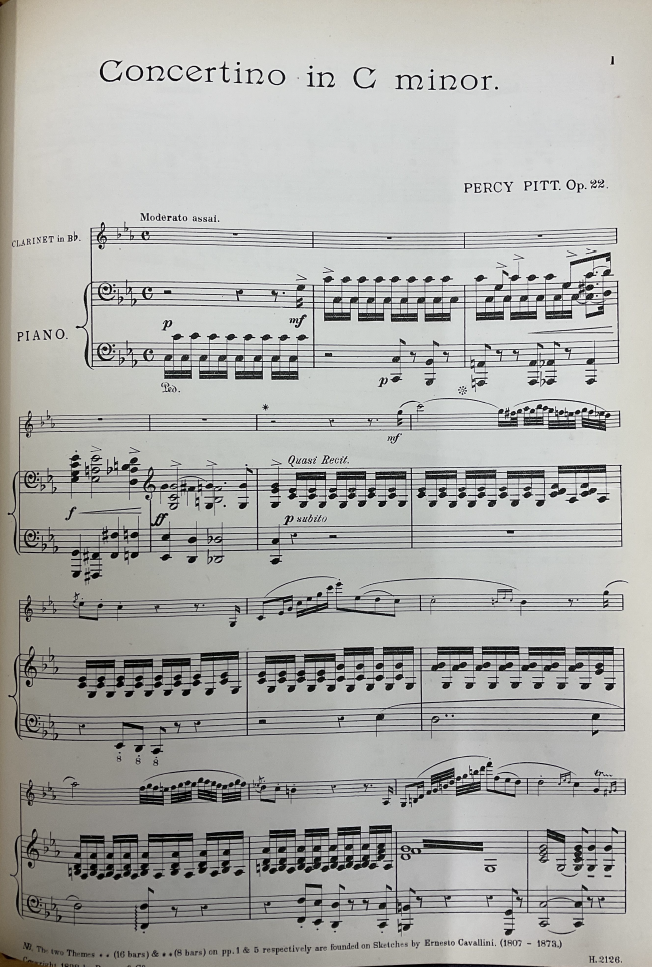

It is more than likely that Manuel Gómez knew of this piece through the clarinet method written by Antonio Romero y Andía (1815-1886), a treatise that the Sevillian clarinetist Gómez learned about during his years of study in Madrid. In the second edition of the method, published in 1860, Romero included several solos from operas by Bellini, Rossini, Paccini, and Salieri, along with two concert pieces: Concerto No. 6 by Iwan Müller (1786-1854) and the aforementioned concerto by Cavallini. From the latter Antonio Romero includes the complete first movement (Fig. 4).12 On the first page of the Boosey & Co. edition (1898), the following sentence appears: “The two Themes (16 bars and 8 bars) on pages 1 and 5 respectively are founded on Sketches by Ernesto Cavallini” (Fig. 5); this seems to strengthen the theory that the source of these themes were indeed the pages of Romero’s method and not the first edition of the concerto published in 1832.

Manuel Gómez was a great admirer of Cavallini’s work. One of the most important performances in his musical career was his first solo concert with orchestral accompaniment in the British Isles. The concert was held on July 2, 1887, at the Royal Albert Hall in London as part of the commemorations for the Jubilee of Queen Victoria. On this occasion, Manuel performed the Fantasy based on motifs from “La Sonnambula.” Years later, he also chose a composition by Cavallini for the concert presentation of the Gomez-Boehm clarinet, a model of clarinet specially designed for him by the English maker Boosey & Co.13 This concert took place on September 1, 1900, with the piece Adagio and Tarantella.14

Figure 5. Pitt’s Concertino, first page, piano part. Boosey & Co., London, 1898. British Library, signature: h.2189.f.(12).

Another fundamental composer for any clarinetist, and one that Manuel played frequently, was Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826). In his first concert on British soil, on July 6, 1884, he performed the Grand Duo Concertante for clarinet and piano by this author, a piece he would play again on at least nine more occasions.15 In January 1894, Manuel had performed the Concertino op. 26, for clarinet and orchestra by Weber, and in December of the following year, he had the opportunity to play the Concerto No. 2, op. 74. In 1897, the year of composition of Pitt’s Concertino, the memory of those performances must have been very recent for both the English composer and the Spanish clarinetist. When studying in detail Cavallini’s Concerto No. 2, the influence of Weber’s clarinet pieces is noticeable, something that Pitt emphasized in his work, as we shall see, when taking the Weber’s Concertino as a model.

THE PREMIERE

The genesis of Pitt’s Concertino must be situated in the central months of 1897, with the premiere taking place at the Queen’s Hall in London on Saturday, October 9, 1897, at 8:00 p.m. The concert was part of the Promenade Concerts season of that year, with Henry J. Wood conducting the Queen’s Hall Orchestra. These popular concerts were characterized by the high number of works programmed, by today’s standards. On the day Pitt’s Concertino was premiered, 18 other pieces were performed, all lasting between five to ten minutes. These works can be divided into three groups: the first with works that are part of the current concert repertoire, with composers like Suppé, Haydn, Wagner, Gounod, Mendelssohn, and Rossini; the second, with concertante pieces by Wieniasky, Koenig, Popper, and Blumenthal that are part of the repertoire of cellists, trumpeters, and singers; and third, works by several British composers active in those years like Sullivan, Cowen, Squire, and Somerset.16

Figure 6. Pitt’s Concertino, piano part, Più lento, mm. 138-147, Bassus Ediciones, Madrid, 2024.

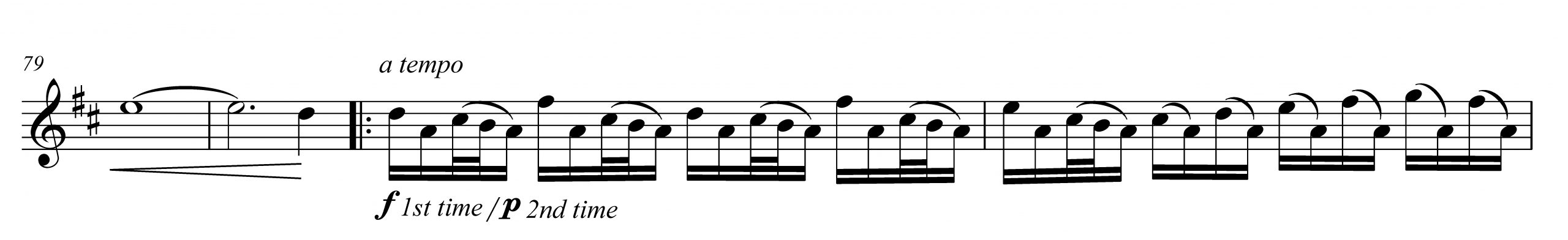

Figure 7. Pitt’s Concertino, clarinet part, mm. 79-82, Bassus Ediciones.

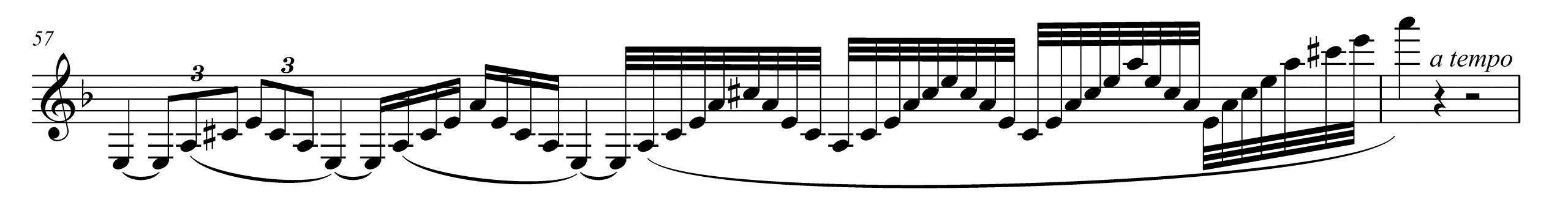

Figure 8. Pitt’s Concertino, clarinet part, mm. 57-58, Bassus Ediciones.

Manuel Gómez had the opportunity to perform Pitt’s Concertino on at least three more occasions: in February and March 1898 and in November 1900, the latter in Liverpool and playing with his brand-new Gomez-Boehm clarinet. The reception from the press was extraordinary, both in London—where it was noted that Gómez “walked over [the passages] with an ease that simply took one’s breath away. The furore occasioned by this phenomenal display of virtuosity was naturally tremendous”—and in Liverpool, where a reviewer wrote, “In the execution of the solo part, whose design Weber’s friend Baermann would have delighted in, Mr. Manuel Gomez distinguished himself by an exhibition appertaining to that of the virtuoso. Mr. Gomez’s tone is suavity itself, and his phrasing is incomparable.”17

During the 18 years that Manuel was first clarinet of the Royal Italian Opera Orchestra at Covent Garden (1886-1894) and the Queen’s Hall Orchestra (1894-1904), he played no less than ten times as a soloist. However, this situation changed during his time as first clarinet of the London Symphony Orchestra (1904-1916). To differentiate themselves from the Queen’s Hall Orchestra, the new orchestra decided not to perform popular and light music, filling its concerts only with orchestral repertoire. As a consequence, none of the members of the orchestra had the opportunity to play concertante works as a soloist. This would explain why no more orchestral works were made for Gómez and why he did not perform the Concertino with his new orchestra.

THE STRUCTURE OF THE CONCERTINO

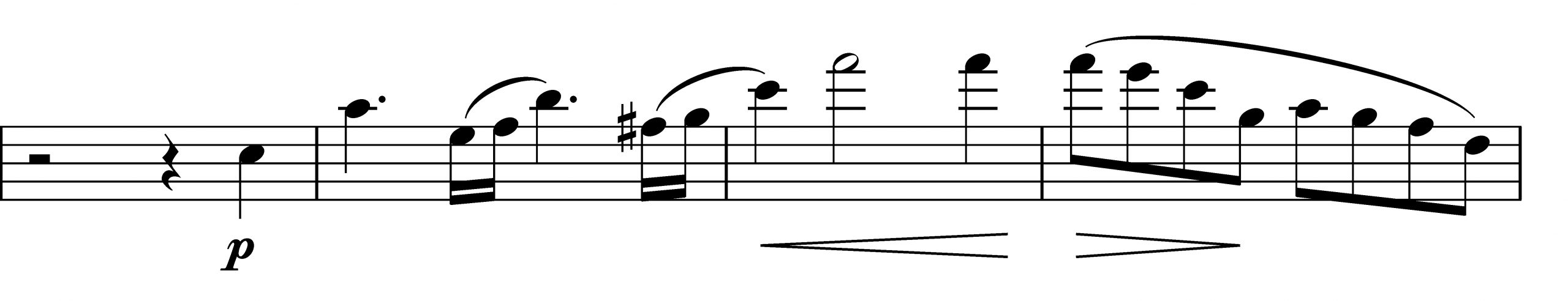

The length and format of Percy Pitt’s Concertino must have been determined by the type of concert for which its premiere was intended. As we have already mentioned, Percy Pitt took the concert piece’s form from a work by Weber, his Concertino, perhaps also at the suggestion of Gómez. From this piece Pitt adopted the title, the key in C minor/E-flat major (which in turn coincided with that of Cavallini), and the general structure. Weber’s Concertino is organized with a short introduction, followed by a theme with variations, a brief central section in Lento tempo, and a final Allegro topped by a coda. Pitt, for his part, following this general structure in three parts and renouncing the introduction, prefers to give special prominence to the first section, developing the two main themes of Cavallini’s concerto and opting for the ABA form, with B being a brief episode of 20 measures in Più lento (Fig. 6). After a long cadenza, Pitt’s Concertino concludes with a final section based on a third Cavallini theme in 16th notes that had already appeared briefly in the first part (Fig. 7).18 This virtuosic section is full of 16th notes in the manner of a perpetuum mobile. The final coda culminates with a series of trills and runs that remind us once again of the endings of Weber’s Concertino and Concerto No. 2.

THE CADENZA

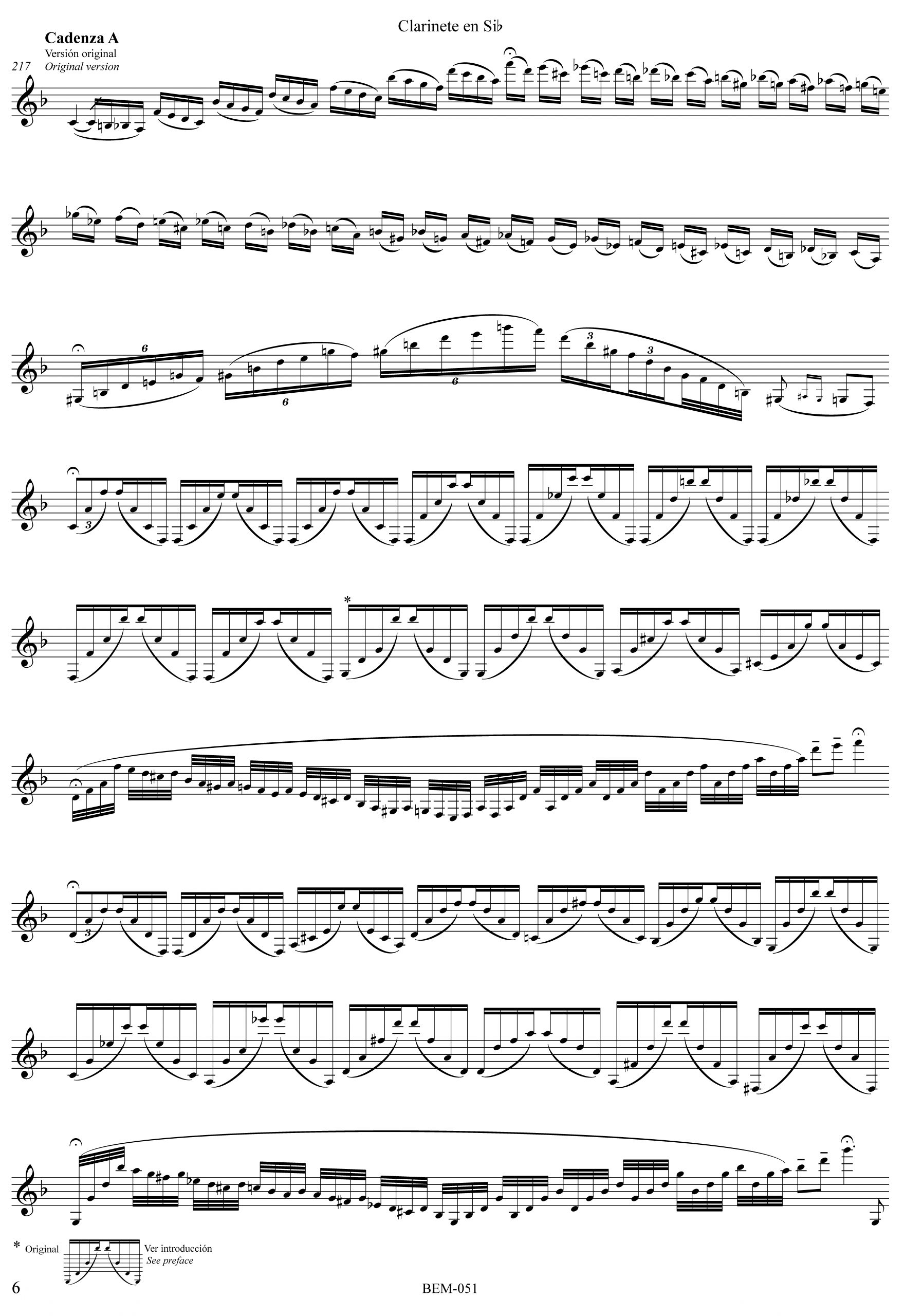

Figure 9a. Pitt’s Concertino, clarinet part, Cadenza A, Bassus Ediciones.

The central part of the work is occupied by an extensive cadenza of quasi-violinistic virtuosity, although it is not the only part of the work in which we can find these characteristic designs (Fig. 8). Pitt also provides a shorter and simpler optional cadenza (cadenza B), but, if performed with the original version, which is almost five minutes long, it becomes little less than the slow movement of a concerto. Due to its importance within the work, we will examine it in a little more detail.

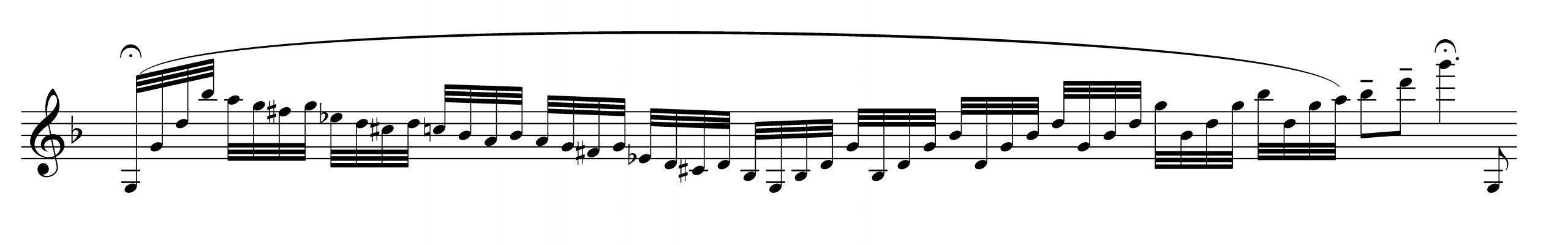

Figure 9b. Pitt’s Concertino, clarinet part, Cadenza A, Bassus Ediciones.

Figure 10. Pitt’s Concertino, clarinet part, Cadenza A (detail), Bassus Ediciones.

Figure 11. Adagio by Albinoni-Giazotto, mm. 30-38. Example created by author.

Figure 12. Pitt’s Concertino, second theme.

Cadenza A can be divided into two distinct sections and a coda (Fig. 9). The first section is preceded by a brief introduction that acts as a bridge between the last piano chord and the first arpeggios in a violinistic manner that characterize this initial section. Curiously enough, in addition to the numerous arpeggios, in this section there are parts that seem to anticipate by half a century certain passages of the violin cadenzas of the famous neo-baroque Adagio by Albinoni/Giazotto (Figs. 10 and 11).

The second section has a certain lyrical quality that contrasts with the previous part. Here Pitt uses one of the themes that appeared earlier (Fig. 12) and expands it by establishing a dialogue between that theme and its accompaniment with rapid arpeggios that present the harmony (see Fig. 9b). The cadenza culminates with a small coda accompanied by three piano chords before addressing the final section of the work. This cadenza is a real challenge for the clarinetist and shows us the amazing mastery of the instrument that Manuel Gómez must have had.

THE CONCERTINO SOURCES

The manuscripts of the Pitt Concertino, both in its version for clarinet and orchestra and for clarinet with piano accompaniment, have not been found yet. Sadly, there is a good chance that both the manuscripts and the orchestral version were lost during the terrible bombings that London withstood during World War II. History has been hard on the archives in which it may have been stored. On the night of May 10, 1941, the English capital suffered one of the heaviest bombings of the entire war. An incendiary bomb fell on the Queen’s Hall and it was completely destroyed by the flames. Everything that was kept inside was lost; it is quite possible that the orchestral version of Pitt’s Concertino was among the losses. About a year earlier, on April 16, 1940, a flying bomb had fallen into the Gómez house in London, killing Manuel’s wife, Adela, and her oldest daughter Adela Isabel on the spot.19 The younger daughter, Marice Elena, was found badly wounded; her mother had protected her with her body upon hearing the arrival of the bomb, and although she survived, she never fully recovered. The house was completely destroyed and only a few personal belongings could be recovered from the rubble. Among them was Manuel’s own clarinet, now in the Museum of the Real Conservatorio Superior de Música in Madrid, but Gómez’s personal music archive was completely lost.

And what about Boosey & Co., the music publisher? Could printing proofs and even manuscripts be preserved? The archive of the company is now kept at the Horniman Museum in London, but, unfortunately, nothing related to the Pitt’s Concertino is found there. In September 1913 there was a severe fire at the Boosey factory; there is the possibility that those documents were also lost in the fire. And Percy Pitt’s legacy? It seems that there is nothing like an archive in which Pitt’s legacy is saved—in any case I haven’t been able to find it yet. As for the family of the composer, few details have been found. As far as we know, it seems that Percy Pitt had two children, Patrick and Biddy; his son died in an accident during World War II and his daughter had to be around her 20s in the 1930s. There is a possibility that, if it exists, the current family preserves some documentation of Percy Pitt, and who knows—perhaps one day the manuscripts will appear stored in a wardrobe or a drawer.

As things stand, the only existing source available has been a reduction for clarinet and piano made by the composer himself and published in 1898 by Boosey & Co (plate number H2126). Three copies of this edition have been consulted: one treasured by the Gomez family, belonging to the Canadian clarinetist Harold M. Gomez, grandson of Manuel Gómez; another preserved in the British Library, signature: h.2189.f.(12); and a last one accessible on the internet.20 The first two are identical. The third differs from the previous two only in the typography of the title and the absence of the edition date on the cover, which suggests that it would be a later reprint.21

In many moments, this reduction provides us with information about the instruments that play each line, as occurs in measures 51 (French horns), 53 (muted strings), 58 (oboe), and 60 (flute), among others. This version also attempts to reflect the complex orchestral texture, frequently duplicating slurs to show the different melodic lines. This substantial complexity in the piano reduction is not unusual in the clarinet repertoire. The Nielsen and Françaix concertos are good examples of that.

THE NEW EDITION

Figure 13. Pitt’s Concertino, cover, Bassus

Ediciones.

After performing Percy Pitt’s Concertino on numerous occasions in concert, a new version of the piano part has been realized with slight, although numerous, modifications that I believe are more suitable for chamber music (Fig. 13). Thanks to pianist and researcher Ana Benavides, the most complex passages have been adapted to the piano technique, always respecting the essence of the arranged version by the composer himself. As for the clarinet part, the obvious editing errors have been corrected and the notable differences in terms of key signature changes between the piano and clarinet parts have been explained. Also corrected were the measures of the Piu lento where there were many important typographical errors in the transposition of the B-flat clarinet.

CONCLUSION

Due to his preeminence and fame, Manuel Gómez attracted the attention of several composers who made works dedicated to him. Of all these, Percy Pitt’s Concertino is the most ambitious, the one with the greatest technical difficulty, and the largest. It is also an exceptional piece in the British concertante repertoire for clarinet and orchestra, and one of the few examples of works of this type and from that period in the history of music (the end of the 19th century) within the clarinet repertoire. Therefore, I believe that both from a historical and artistic point of view, a new edition that can make a work of this style and format accessible is necessary.

Hopefully, this article about the Pitt’s Concertino will draw attention to the piece and thus clarinetists and researchers will look for the manuscript in UK archives. It may be in the possession of Pitt’s descendants or among the collections of an archive that has not yet been consulted. Regardless of whether the manuscript is ever found, the existing version with piano reduction is worthy of study and performance.22

ENDNOTES

1 F. G. Rendall, The Clarinet, 3rd ed. (London: Ernest Benn Limited, 1954), 110.

2 D. Chamier, Percy Pitt of Covent Garden and the B.B.C. (London: Edward Arnold & Co., 1938), 55.

3 G. Hodgkins and R. Taylor, Elgar and Percy Pitt, Part I (The Elgar Society Journal. Vol. 8/No. 7. November 1994), 306-307. This letter is undated. Just before the text, there is a musical joke about the great success that Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1 was having.

4 In Discography of American Historical Recordings. Retrieved January 5, 2025, from https://adp.library.ucsb.edu/names/109716.

5 The Musical Times 74 no. 1079 (Jan. 1933), 79.

6 Fernando Palatín y Garfias (1852-1927). Violinist. He had a successful career performing in the most important auditoriums in Europe. As a student of Jean-Delphin Alard (1815-1888) at the Paris Conservatory, he won the First Prize for violin in 1870.

7 P. Weston, Clarinet Virtuosi of the Past (Corby: Fentone Music Limited, 1971), 221. No documentary evidence has been found of this statement. It is possible that Manuel collaborated as an occasional member of the orchestral staff in sporadic performances called by Rose, his teacher at the Conservatory. I am grateful to Philippe Cuper for his contribution to this piece of information.

8 These are two pieces with piano accompaniment, but unfortunately the pianist’s name does not appear in the credits. Who was the accompanist then? In those years, Percy Pitt was the pianist of the Queen’s Hall Orchestra, the one who accompanied the soloists in their piano recitals at the Proms and summer tours. In addition, Pitt appears numerous times in recordings from those years for The Gramophone Co., both as conductor of the orchestra and as pianist accompanist to the singers. It is therefore quite possible that the pianist of these recordings was Pitt himself. The catalog numbers of the two pieces are Caro Nome (GC6030) and Chanson Napolitaine (GC6031).

9 Catalog number: G 2-053068.

10 Ch. Kennedy, Manuel Gómez “The best clarinet player in the world” (Breslavia, Poland: Amazon, 2023), 100.

11 Premiered by the composer himself on June 7, 1830, in Milan. The success obtained opened the doors of the La Scala orchestra in Milan to Cavallini, with him being its clarinet soloist between 1831 and 1851. The Concerto was published in 1832 by the publisher Benedetto Carulli in Milan. For more information see Concerto n. 2 in C minore per Clarinetto e Orchestra, published by Edizioni Eufonia. Historical introduction by Adriano Amore.

12 A. Romero, Método completo de clarinete, 2nd ed. (Madrid: Ed. A. Romero, 1860), 168-169. Antonio Romero and Ernesto Cavallini met during the tour that the Italian virtuoso made through Spain between 1851 and 1852. The result of that meeting was the dedication to the Spanish clarinetist in Cavallini’s piece Three Variations and the eventual delivery of several of his compositions. Among them, surely, the concerto in question, which must have pleased Romero enough to include it in the second edition of his most important didactic work.

13 See: P. Rubio, “Manuel Gómez and the Gomez-Boehm Clarinet: The Legacy of a Legendary Clarinetist, Part II – The Gomez-Boehm Clarinet,” The Clarinet 47 no. 3 (June 2020). The Gomez-Boehm clarinet was first offered in Boosey & Co.’s 1902 catalogue and just three clarinets made in this design were recorded from 1912. See Jocelyn Howell, “Boosey & Hawkes: The rise and fall of a wind instrument manufacturing empire,” Ph.D. thesis, University of London, 2016, vol. 2, p. 26.

14 See: Kennedy (2023) p. 137.

15 See: Kennedy (2023) p. 283.

16 In Proms the World’s Greatest Classical Music Festival. Retrieved January 5, 2025, from https://www.bbc.co.uk/events/ecvbj5.

17 Kennedy (2023), pp. 99-101. Heinrich Baermann (1784-1847) was the great clarinet player of the 19th century for whom Weber wrote his concertos.

18 This theme also appears in one of Cavallini´s 30 Caprices (Caprice n. 19, IV variation).

19 I thank Charlotte Kennedy for providing the date of this event.

20 This last version can be found on IMSLP.

21 To trace the connections between Pitt’s work and the themes extracted from the first movement of Cavallini’s Concerto, the following publications have been consulted: Cavallini, E. (1832). Concerto per Clarinetto con Acompagnamento a Grande Orchestra (Milan: Ed. Benedetto Carulli. Archive L. Magistrelli, Milan); Romero, A. (1860). Método completo de clarinete. 2nd edition (Madrid: Ed. A. Romero. Archive P. Rubio, Madrid); Cavallini, E. (2010). Concerto n. 2 in Do minore per Clarinetto e Orchestra (Reduction for clarinet and piano published by Edizioni Eufonia, catalog number 10889C) and Cavallini, E. (2011). Concerto n. 2 in Do minore per Clarinetto e Orchestra (Score for clarinet and orchestra published by Edizioni Eufonia, catalog number 11941C).

22 A recording of Pitt’s Concertino and other pieces dedicated to Manuel Gómez, with Pedro Rubio on clarinet and Ana Benavides on piano, will be available at the end of 2025.

Pedro Rubio is a clarinet professor at the Conservatorio Superior de Música de Castilla y León (COSCYL) in Salamanca and at the Escuela Superior de Música Forum Musikae in Madrid. In 2007 he founded the publishing house Bassus Ediciones, whose principal objective is the restoration and retrieval of the Spanish clarinet repertoire of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century. He was one of the artistic directors of ClarinetFest® 2015 in Madrid.

Pedro Rubio is a clarinet professor at the Conservatorio Superior de Música de Castilla y León (COSCYL) in Salamanca and at the Escuela Superior de Música Forum Musikae in Madrid. In 2007 he founded the publishing house Bassus Ediciones, whose principal objective is the restoration and retrieval of the Spanish clarinet repertoire of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century. He was one of the artistic directors of ClarinetFest® 2015 in Madrid.

Comments are closed.