Originally published in The Clarinet 53/1 (December 2025).

Copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

Pedagogy Corner

PART 1 — INHALATION:

WHEN BALANCE BREATHES FOR YOU

by Shawn Copeland and Jackie McIlwain

We came into this world with the instinct to breathe. No one taught us the first inhale. It arrived as a quiet unfolding of ribs and diaphragm, a reflex that welcomed us into a relationship with the world. If breath is so natural, why bring it into pedagogy? Because life intervenes. Families, schools, cultural messages, and the pressures of achievement shape how we move and how we breathe. Bodies learn patterns from what we practice and from what we survive. Some information we have received is accurate, while some is more well-intentioned. Over time, we carry a patchwork of cues that add work where none is needed. The result could be a breath that is loud when we want quiet, late when we need readiness, or small when the music asks for space.

Balance is the condition that returns the inhale to its primal design. Balance is not a position. It is a living coordination that involves the feet, legs, pelvis, spine, ribs, shoulder girdle, arms, and head. When this coordination is available, the inhale occurs as a reflex synchronized with the musical task. No grabbing. No gulping. No collapse.

Without balance, the body reaches for control. We lift the shoulders or pin them. We spread the lips or pull the corners. We press the tongue down to force an open throat. We push the belly forward because we were told to breathe into it. None of this opens space for air. It narrows the airway and agitates the nervous system. A strained inhale is the body’s way of saying it does not feel safe. When the system shifts from performance pressure to embodied safety, breath organizes itself. This is not abstract. It is practical. It is teachable.

THE ESSENTIALS OF A FREE INHALE

- The inhale is a whole torso event. The ribs, spine, diaphragm, lungs, pelvic floor, and suspended throat structures work together.

- The lungs do not pull air in. Surrounding structures change shape and pressure, and air flows as a result. The ribs are the primary bony drivers with many small joints.

- The upper ribs matter greatly. Significant lung volume lives high and back under the collarbones.

- The diaphragm organizes the inhale.

- The shoulder girdle floats. As ribs swing, the sternum rises and the clavicles move a little. Forbidding all movement often creates more tension and less air.

- “Open throat” is not a muscle action. The pharynx is open when not swallowing.

- Reflexive inhalation can be trained. Finish the exhale and wait without gripping so the costal cartilages and elastic tissues invite an easy return.

- A free breath is a product of a balancing body. When weight is carried through bone, muscles are free to move those bones rather than hold them. That freedom is what allows quiet, responsive breathing.

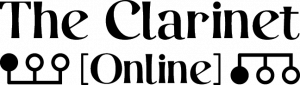

Figure 1: Upper Respiratory Spaces

MAP THE PATHWAY OF AIR, THEN REMOVE INTERFERENCE

On an inhale, air is either filtered and warmed in the nasal passages and sinuses or travels over the tongue. It then passes through the pharynx and enters the trachea, which sits in front of the esophagus, before continuing into the lungs. These passages are formed by tissues suspended between the base of the skull and the hyoid bone. They remain open when you do not contract them. Let them rest so the airway stays spacious (see Figure 1: Upper Respiratory Spaces).

Confusing the locations of the trachea and esophagus often creates a noisy, effortful inhale. When the map is off, the body tries to steer the air with throat effort. Try this: place a relaxed hand at the front of your neck without squeezing. Swallow and feel the larynx move. The airway sits in front of the esophagus. Breathe and notice whether any extra effort arrives under your hand.

The tongue and pharyngeal muscles serve swallowing, articulation, and voicing. They do not need to contract for breathing.

CLARINET APPLICATION

- When breathing through the nose, let the tongue rest high and forward without pressing into the throat.

- For playing, inhale gently around the mouthpiece with soft lips, avoiding corner pulling or tongue tension.

LUNGS ARE TISSUE, NOT MUSCLE

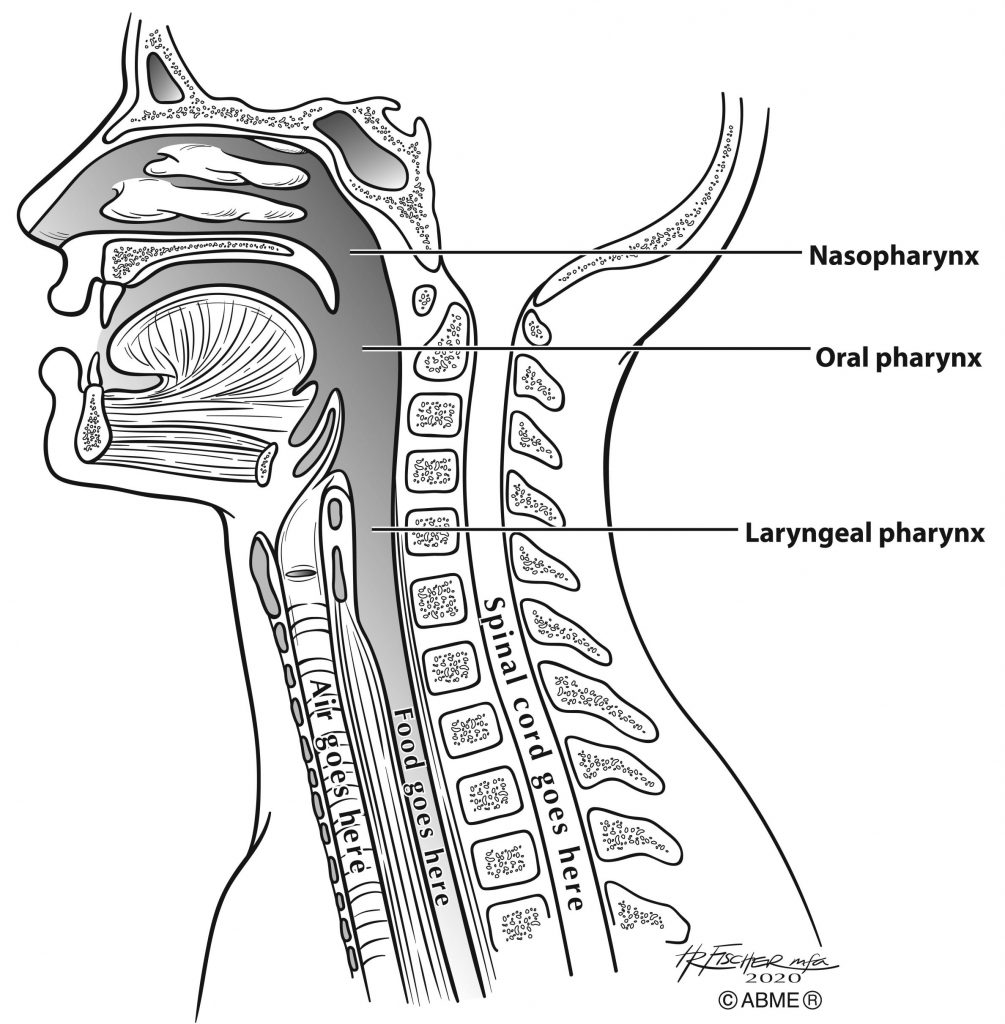

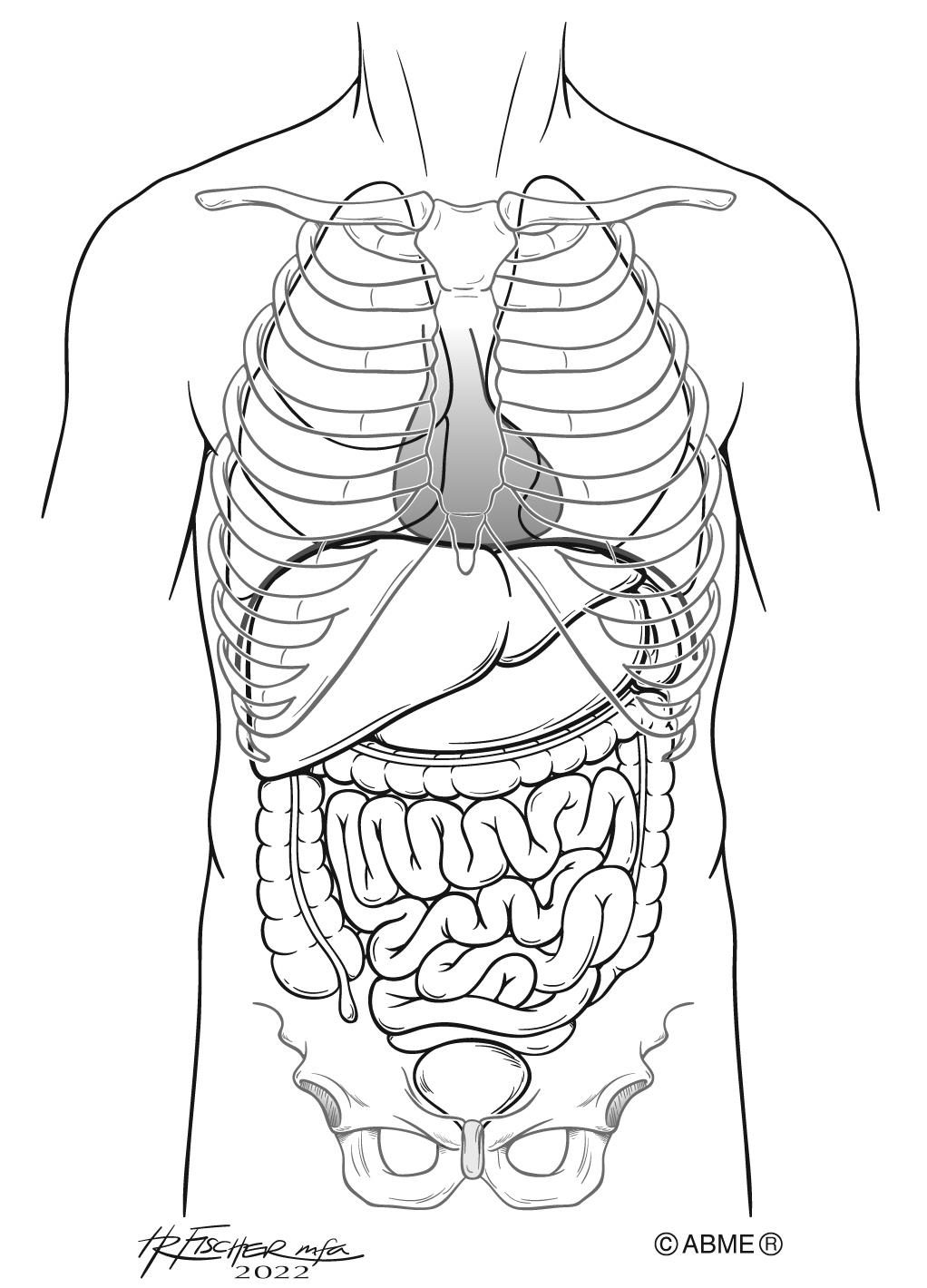

The lungs are protected by your ribs. The tops of the lungs rise above the collarbones, and the bases rest near the bottom of the sternum and the dome of the diaphragm. They are three-dimensional and take up most of the rib cavity from front to back and top to bottom. Everything above the diaphragm in your torso, apart from the heart, is lung (see Figure 2: Views of the Lungs).

Imagine sponges made of tiny elastic sacs. The lungs are moist, stretchy, and designed for efficient gas exchange. They are moved by the ribs and diaphragm through changes in shape and pressure. When ribs swing up and out, they change the volume of the rib cavity, and the lungs fill because the pressure drops. We breathe because we move our ribs, not the other way around.

Figure 2: View of the lungs

RIBS: YOUR BREATHING JOINTS

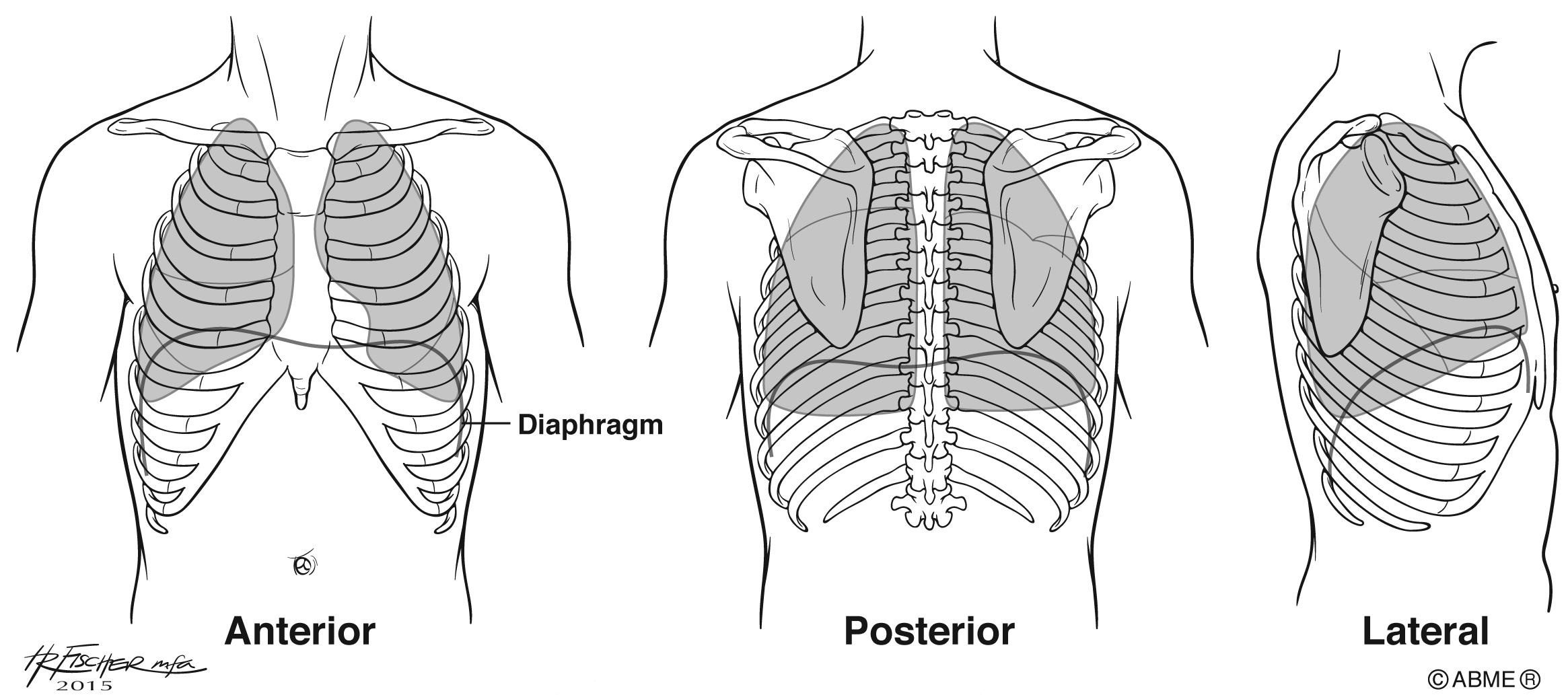

You have twelve pairs of ribs. Each rib meets the spine at small joints, and the first ten also connect in front through costal cartilage to the sternum. Think breathing joints, not a cage (see Figure 3: Breathing Joints). The cartilage in front acts like a spring that assists the return of breath.

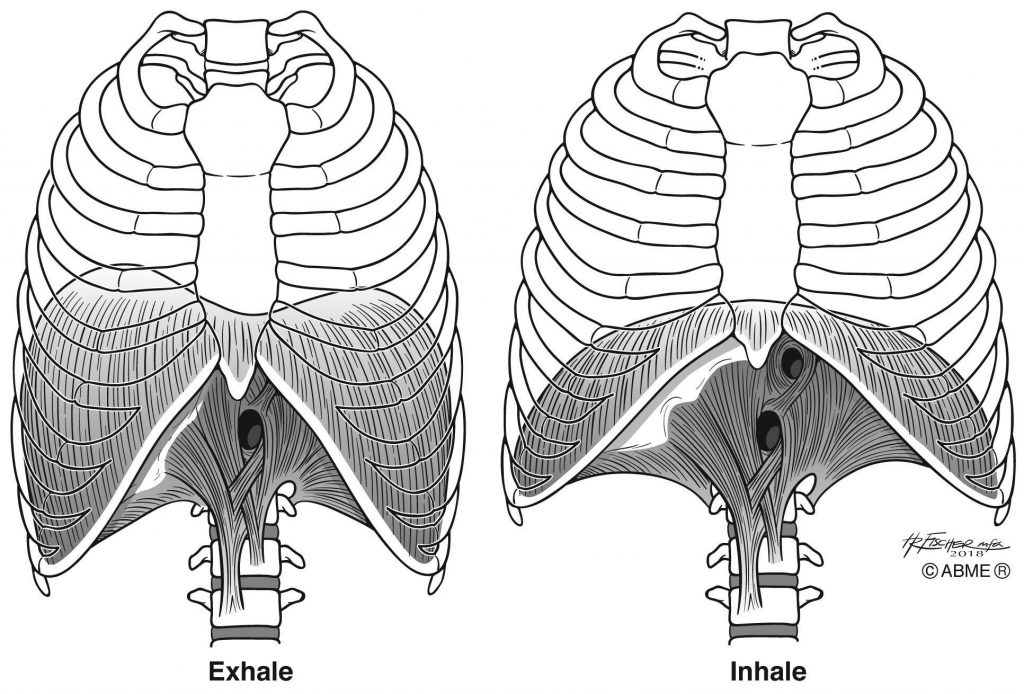

Ribs do not expand themselves. They swing, and that swing changes the space within the torso in all directions. The expansion is forward, to the sides, and into the back (see Figure 4: Diaphragm and Ribs on Exhalation and Inhalation). In our experience, this is the most common missing element in the breathing maps of clarinetists. It is the movement of ribs that invites air. Are yours moving?

Figure 3: Breathing Joints

DIAPHRAGM AND ITS PARTNERS

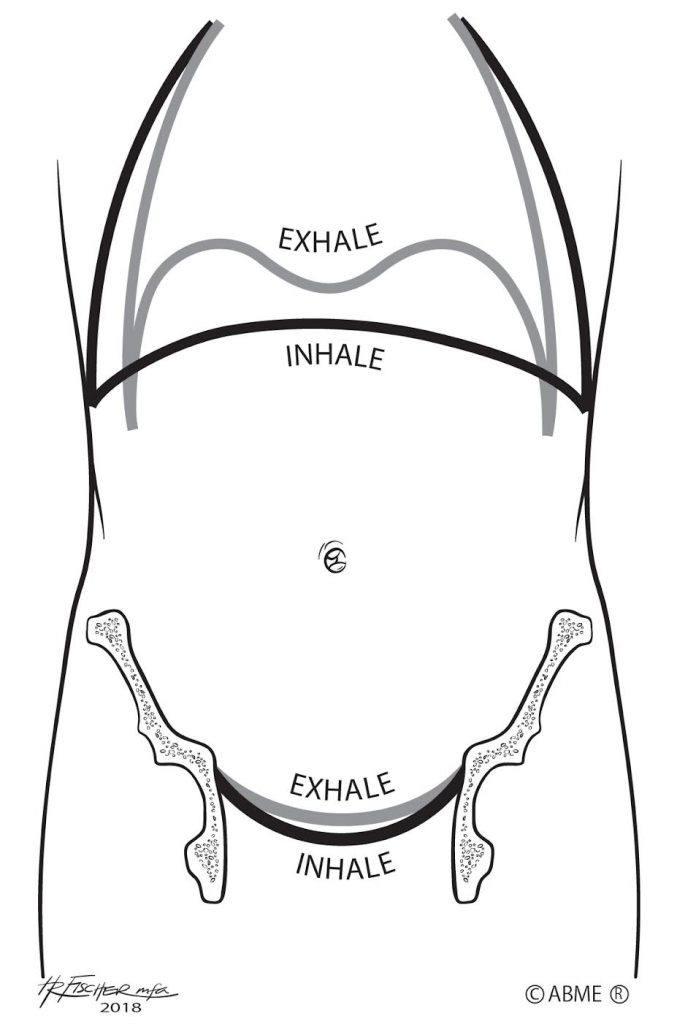

The diaphragm is a dome-shaped sheet of muscle that attaches around the inner lower ribs and the sternum and to the upper lumbar spine through its right and left crura. When it contracts, it descends a small distance and widens the circumference of the lower ribs, which increases the volume of the rib cavity and lowers pressure so air flows in. Refer to Figure 4. The abdominal organs yield (move) in all directions and the pelvic floor softens. None of this requires pushing the belly forward (see Figure 5: Relationship of Diaphragm and Pelvic Floor in Breathingand Figure 6: Organs of the Thoracic and Abdominal Cavities).

The diaphragm does not act alone. As it descends, the lower ribs swing and rotate, the spine subtly adjusts, and the abdominal wall responds with elastic give rather than a brace. For clarinetists, the useful cues are width and buoyancy. Sense the ribs spreading around the back and sides from about ribs seven to ten, while the clavicles float. Keep the abdominal wall quiet and available rather than firm or pushed. This preserves voicing options, keeps the throat neutral, and supports a silent, timely inhale matched to the phrase.

Figure 4: Diaphragm and Ribs on Exhalation and Inhalation

Figure 5: Relationship of Diaphragm and Pelvic Floor in Breathing

Figure 6: Organs of the Thoracic and Abdominal Cavities

FLOATING SHOULDER GIRDLE

Rib movement is fundamental to unimpeded respiration, and it is linked to the arm. The first joint of the arm is the sternoclavicular joint, where the clavicle meets the sternum. When ribs and sternum rise on the inhale, the clavicles can float with them. The scapula joins with the clavicle, and the humerus joins the scapula. This entire chain can remain mobile and responsive during inhalation when we do not interfere. That matters because a large portion of lung volume lives in the upper third of the torso, directly under the shoulder girdle. Free the girdle and the upper ribs can join the breath. Holding the shoulders still or tightening the armpits significantly interrupts this coordination.

Experience: Pause for a moment as you are reading and hug yourself, placing your fingertips in your armpits and the palms of your hands over the sides of your ribs. Breathe deeply and experience the movement of the ribs rising up and out, filling the space beneath the shoulder girdle. In contrast, tighten this space by squeezing the armpits tightly and notice how this tension interferes with the movement of the ribs and the overall quality of your breath.

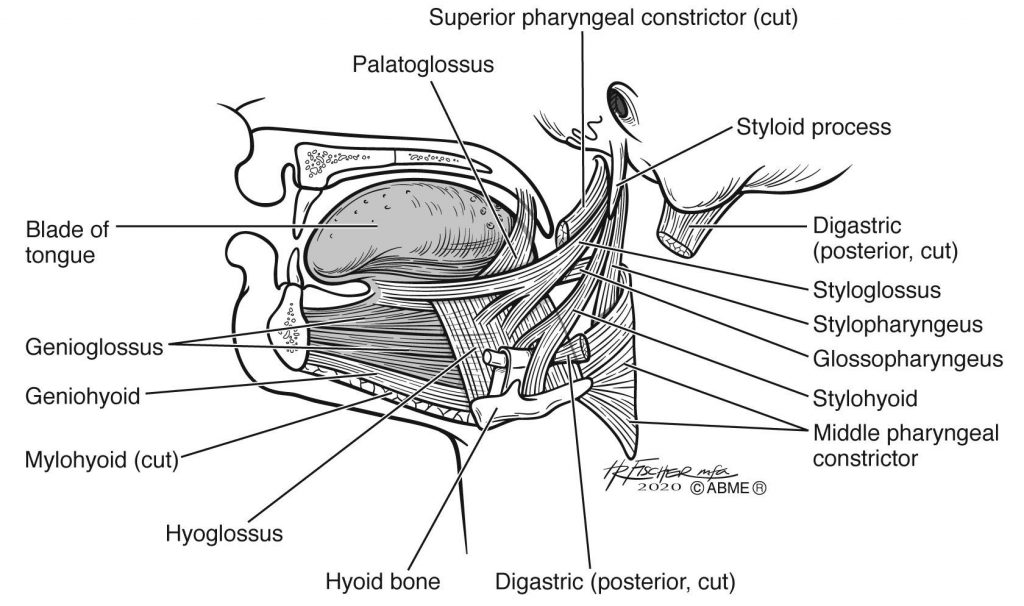

Figure 7: Extrinsic Muscles of the Tongue

THE OPEN THROAT

The pharynx is not a rigid tube. It is suspended from the cranial base by small muscles, which allows openness and mobility for breath, swallowing, and voice. These muscles assist with swallowing. When they are not contracting, the throat is already open. (See Figure 7: Extrinsic Muscles of the Tongue.) These extrinsic muscles are the muscles that form the back of the throat or pharyngeal cavity.

This is where confusion creeps in. We want a free throat when playing. Directions such as “open the throat” encourage an action, so players depress the tongue to create a sensation of space. That movement narrows the lower pharynx and disturbs tongue position and articulation. Most often, we see that attempts to open the throat cause a swallowing or depression of the tongue, giving us the sensation of more space in the mouth. In reality, this could restrict space in the back of the throat and lead to a low tongue placement.

Why does this work when we hear it in masterclasses? The resting state of the tongue is at the roof of the mouth when the teeth are together. If the jaw moves, the tongue moves with it. The reverse can also be true. If we move the tongue, the jaw also responds. If we map opening the throat as depressing the tongue, what is actually happening is a release in the jaw, which increases resonance in the sound. Thus, we equate the two. This movement disrupts tongue placement and articulation, so we need an alternative route.

A better cue is to imagine the airway as a long, resonant passage from the trachea to the reed aperture. Let the tongue rest forward to shape voicing for range and color. Think length and ease, not constriction.

THE REFLEXIVE INHALATION

One of the paradoxical commonalities between all wind players and singers (with the exception of oboists) is that we inadvertently hold our breath. We have been taught to think of air as a scarce resource, thus managing it to make it last as long as possible all the time. One way this manifests is that every time we take a breath, many of us have been trained to take a full breath, regardless of the phrase length or dynamic we are playing. In the end, we are often left with quite a bit of air left in the tank.

Try this for a moment: exhale (and don’t inhale), now exhale again (see, there’s still air), and exhale a third time (again without inhaling). Now wait without tightening your throat, suspend the inhalation until your body reflexively inhales. Now that you get it, do it again, and this time, notice the quality of that inhalation. Notice the effort, what moves, how does it feel? What is the quantity and quality of the air? It is effortless and full, and it happens in a fraction of a second.

This is available to us all the time if we stop thinking that air is a scarce resource. Air is abundant. What determines your next phrase is less how big you breathe and more how clearly you release the previous one.

BALANCE IS THE PRECONDITION

Shift from a posture mindset to a balance mindset. Balance invites continuous, adaptive movement through the ankles, knees, hips, lumbar region, ribs, shoulders, head, and neck. These areas are your breathing infrastructure. When they are free, the rib joints can spring and the reflexive inhale emerges without a grab.

The body is one connected structure. Words help us focus on parts, yet the parts work as a single design. If one area is tense or out of balance, the whole system adapts. Coordinated breathing is a product of coordinated balance. When tension releases, breathing organizes itself around musical intention.

QUESTIONS TO DEEPEN YOUR CRAFT

- Where do you habitually hold in the moment before you play? Lips, tongue root, neck, upper chest, abdomen, or pelvic floor?

- Do you overfill before short phrases, or do you trust a small inhale that matches the task?

- What changes in color and articulation when you prioritize upper rib swing and back width rather than focusing on only belly movement?

Shawn L. Copeland is a pioneer in the fields of musician wellness and performance training. His innovative, creative, and transformational approach has set him apart as a multidimensional musician, pedagogue, and entrepreneur. His unique methods have established him as a leader, culminating in the founding of mBODYed, LLC, a company that is reshaping the landscape of performance training for musicians, actors, and dancers. Shawn is a performing artist and clinician for Buffet Crampon USA, Gonzalez Reeds, Inc., and the Silverstein Group.

Shawn L. Copeland is a pioneer in the fields of musician wellness and performance training. His innovative, creative, and transformational approach has set him apart as a multidimensional musician, pedagogue, and entrepreneur. His unique methods have established him as a leader, culminating in the founding of mBODYed, LLC, a company that is reshaping the landscape of performance training for musicians, actors, and dancers. Shawn is a performing artist and clinician for Buffet Crampon USA, Gonzalez Reeds, Inc., and the Silverstein Group.

Jackie McIlwain, D.M., is a passionate clarinet pedagogue whose innovative teaching infuses principles of Body Mapping and Alexander Technique, providing fresh ideas and perspectives that not only help her students grow musically but also challenge them to incorporate their whole selves into their music. Dr. McIlwain has been at the University of Southern Mississippi since 2013 and currently serves as associate professor of clarinet. She is also a Buffet Crampon performing artist and Vandoren artist-clinician.

Jackie McIlwain, D.M., is a passionate clarinet pedagogue whose innovative teaching infuses principles of Body Mapping and Alexander Technique, providing fresh ideas and perspectives that not only help her students grow musically but also challenge them to incorporate their whole selves into their music. Dr. McIlwain has been at the University of Southern Mississippi since 2013 and currently serves as associate professor of clarinet. She is also a Buffet Crampon performing artist and Vandoren artist-clinician.

Comments are closed.