Originally published in The Clarinet 52/4 (September 2025).

Copies of The Clarinet are available for ICA members.

Master Class

HOMMAGE À MANUEL DE FALLA BY BÉLA KOVÁCS

by Vitor Fernandes

Hommage à Manuel de Falla, composed in 1994 by the Hungarian clarinetist and educator Béla Kovács, is part of his series of nine homages to great composers. In this work, Kovács evokes the colors and rhythms of Spanish and Andalusian traditional music, which are so remarkable in the musical universe of Manuel de Falla (1876-1946).

From highly pronounced and disruptive accents, often not on the strong beats, to more nuanced moments and strong contrasts of dynamics and character with drama and subtlety, this is a work that, in less than three minutes, takes us on an exploration of the boundaries of the clarinet.

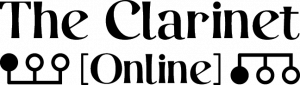

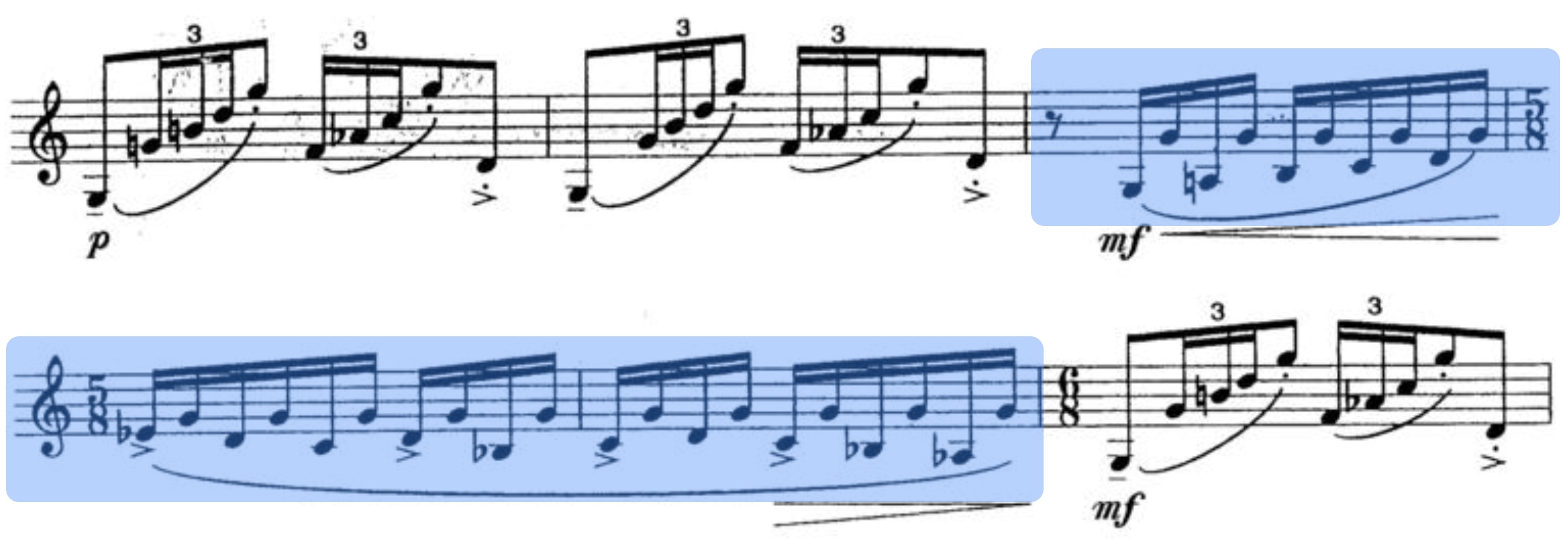

At the beginning, we have an introduction in three sections until arriving at the first Moderato. We begin with an introductory phrase of great intensity, where the repetition of the note D reinforces its dramatic character (see Fig. 1). I like to think of this first moment as a moment of alarm, striving for the greatest possible contrast between the fortissimo—represented by the insistent D—and the pianissimo, which creates lightness and elegance with its accents and short articulation. Notable also is the use of triplets, with an accent on the first note, which, in combination with the articulation, introduces us to the dance-like character of the passage.

Figure 1

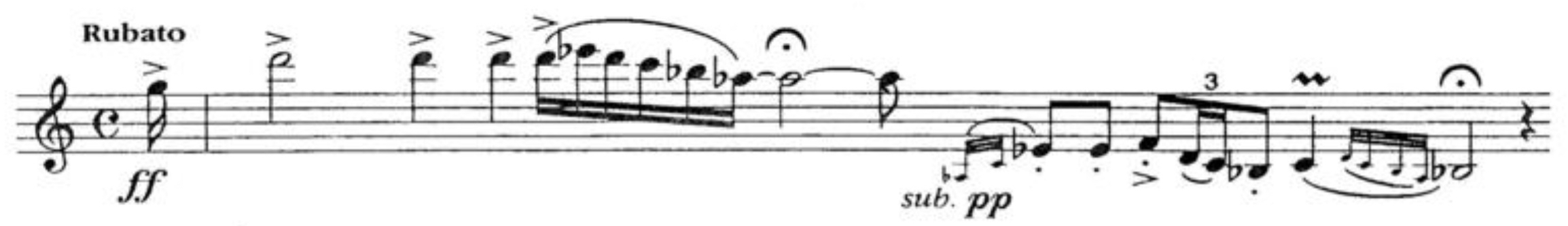

Figure 1 shows the first of the three sections that constitute the introduction. I consider the two following sections simply as developments of this first phrase, more ornamented so as to build the musical intensity leading to the passage that is the transitional bridge to the Moderato (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2

At the first Moderato, finally the composer establishes a steady beat. Sudden changes in dynamics and character should be exaggerated, in order to create more contrast, as in the beginning. The accents should be played lightly and elegantly, always with a sense of “lifting up,” which should create the feel of a dance during the entire passage, similar to what we can hear in the dances of Manuel de Falla’s El sombrero de tres picos.

It is important that the tempo before the second Moderato not be rushed (the composer gives the indication ad libitum), so that there can be greater tension and, consequently, greater musical impact when we arrive at the new motive.

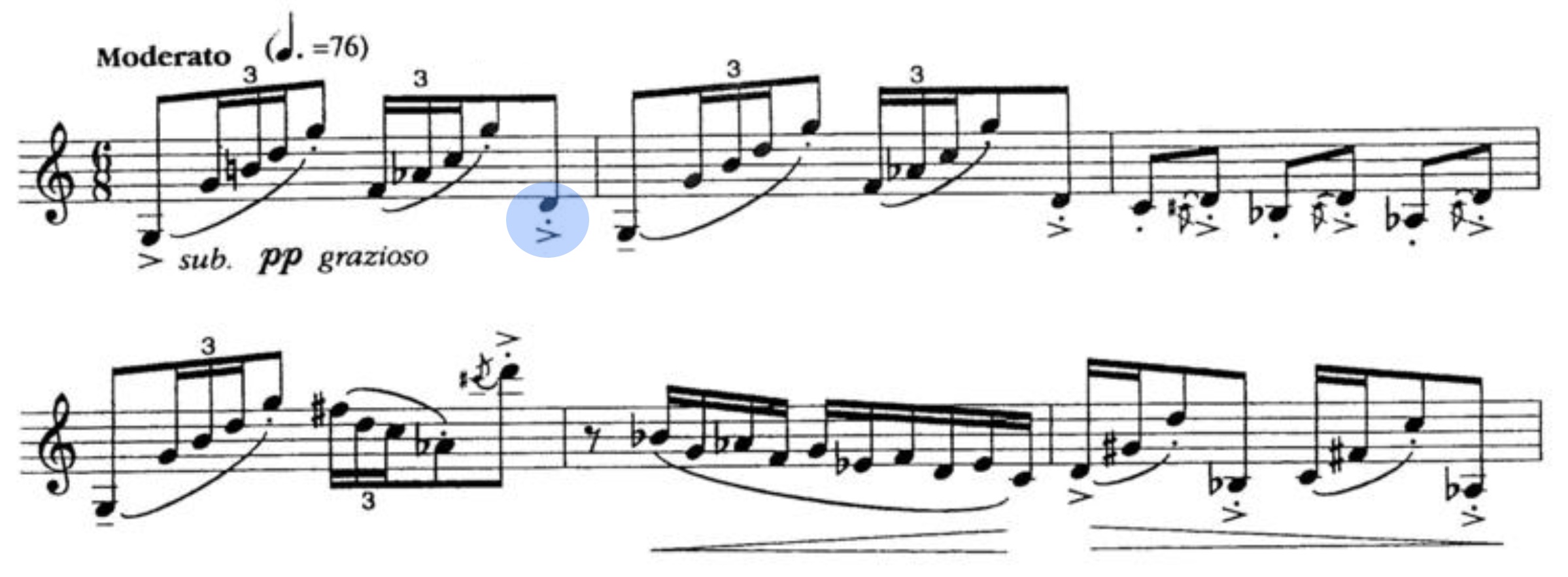

We now arrive to the part that, in my opinion, is the most important motive of this Hommage. Graceful and elegant, it should not be rushed, and we should always give the last note of the rhythmic unit a small disruptive accent, followed by a note with less intensity (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3

These accents will only have real impact if the Moderato is not too fast. In several master classes where I have had the opportunity to listen to and work on this piece, I have noticed the tendency to give preference to speed at the expense of detail in articulation, which seems to me to be an error, for it causes us to lose the grazioso feel of the piece.

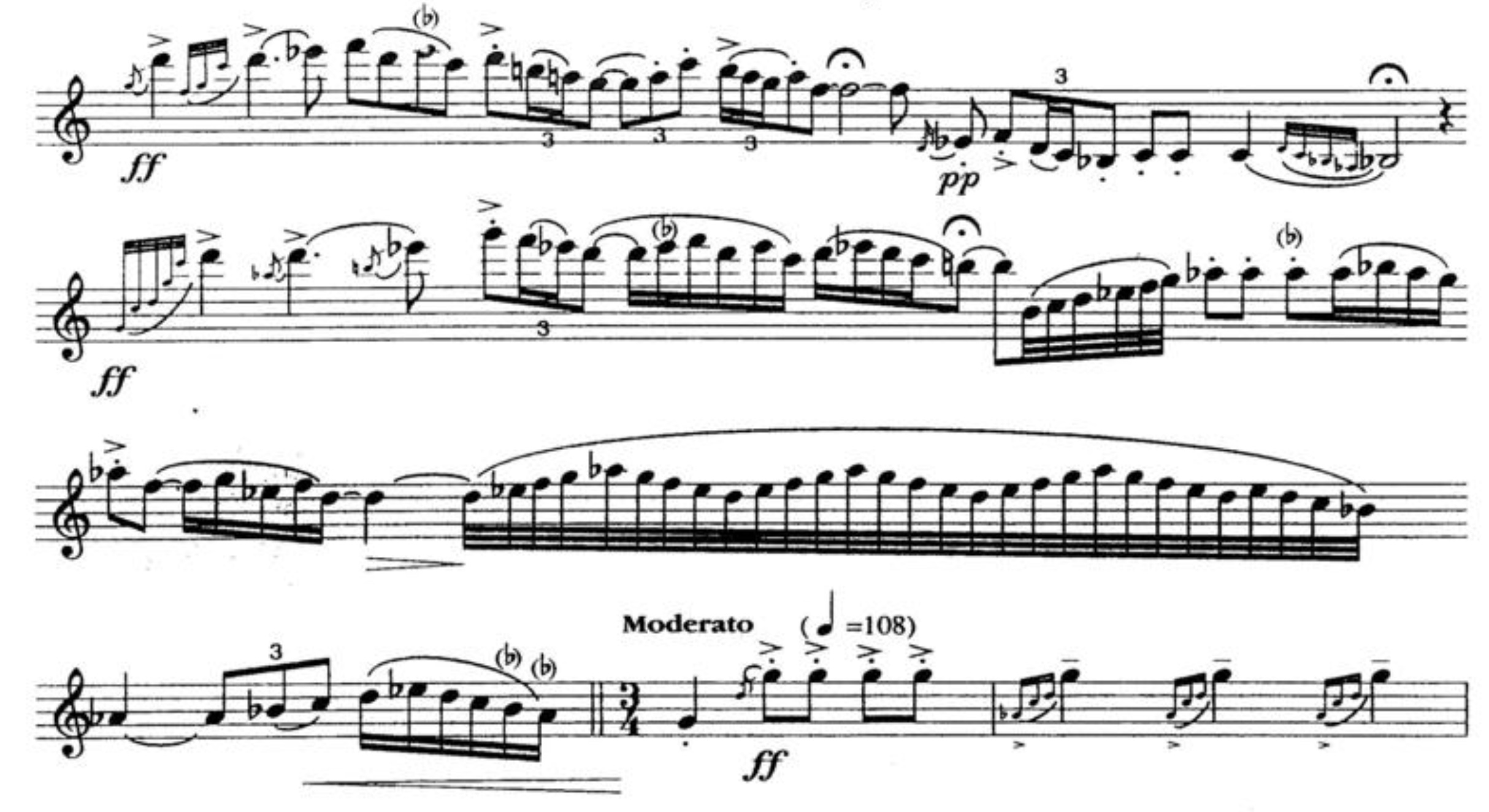

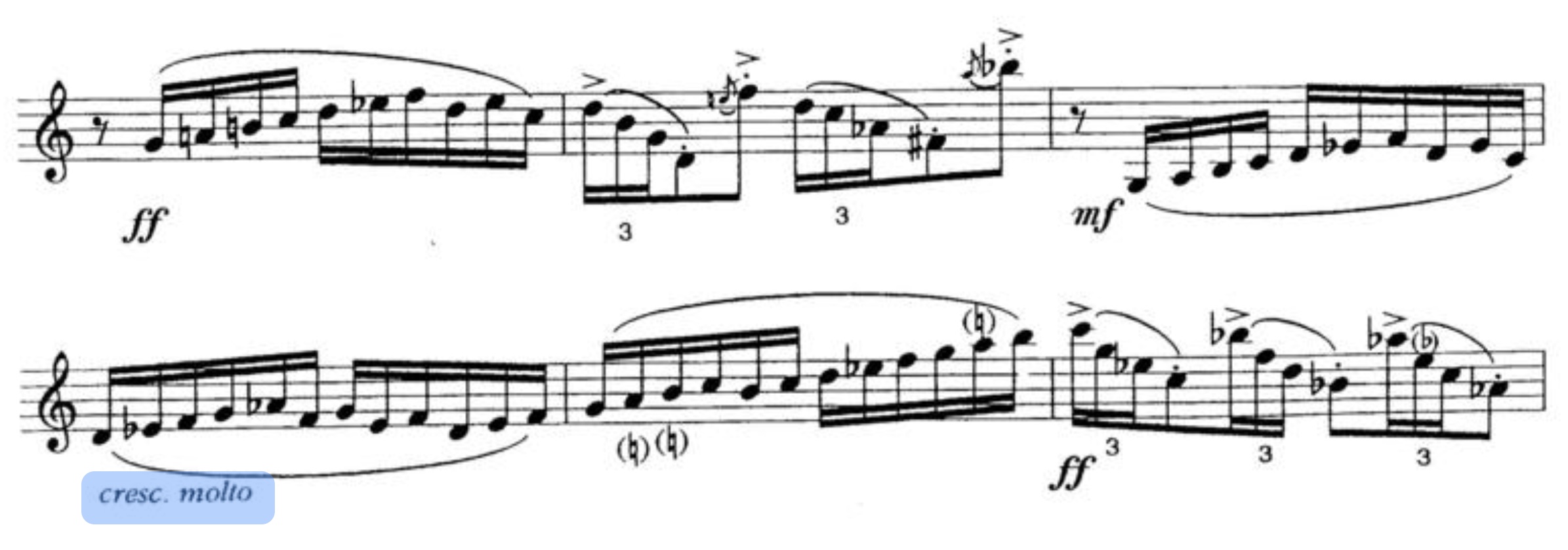

Béla Kovács for the first time introduces a passage or compositional technique frequently found in traditional Spanish music (see Fig. 4). In this passage, I try to highlight only the indicated accents, avoiding an accent on every note of the melodic line. I understand the tendency to do so, but in addition to eliminating the expressive effect of the accented notes, it also works against musical fluidity.

Figure 4

Figure 5

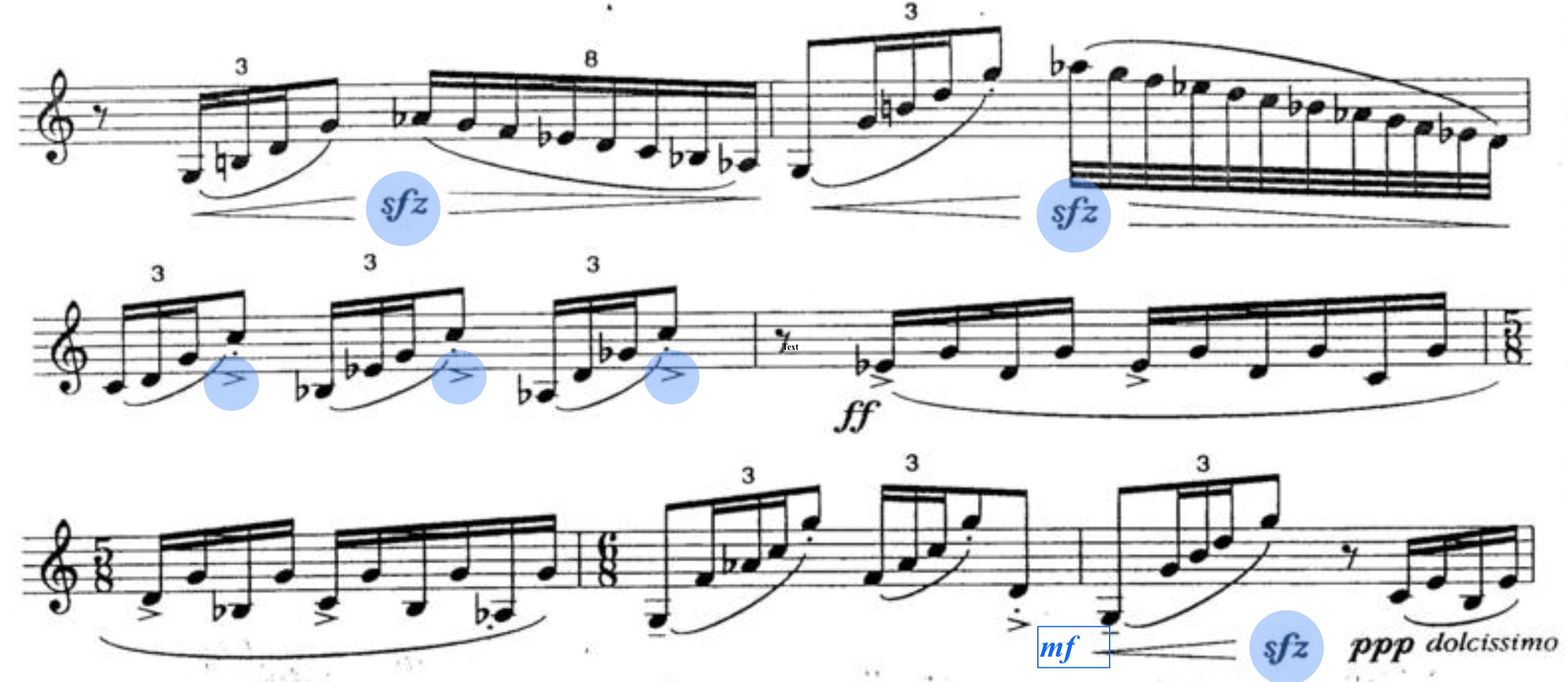

As we approach the end of this section, the dynamic contrast and each sfz indication should be emphatically observed, so as to accentuate the musical intensity and to create a sense of agitation (see Fig. 6).

Figure 6

With quick dynamic variations and accentuation outside the normal metric emphasis, we arrive at the end of this section. Particularly take note of the last crescendo before the ppp dolcissimo; it should be played as if we firmly believed that this is the conclusion of the work, prolonging the rest before going forward. Thus, a pause is created for the player and, at the same time, an instant of expectation in the audience (especially for those who are not clarinetists or who are unfamiliar with the piece), causing listeners, for a few brief seconds, to remain unsure if they are truly at the end or if there is more to come.

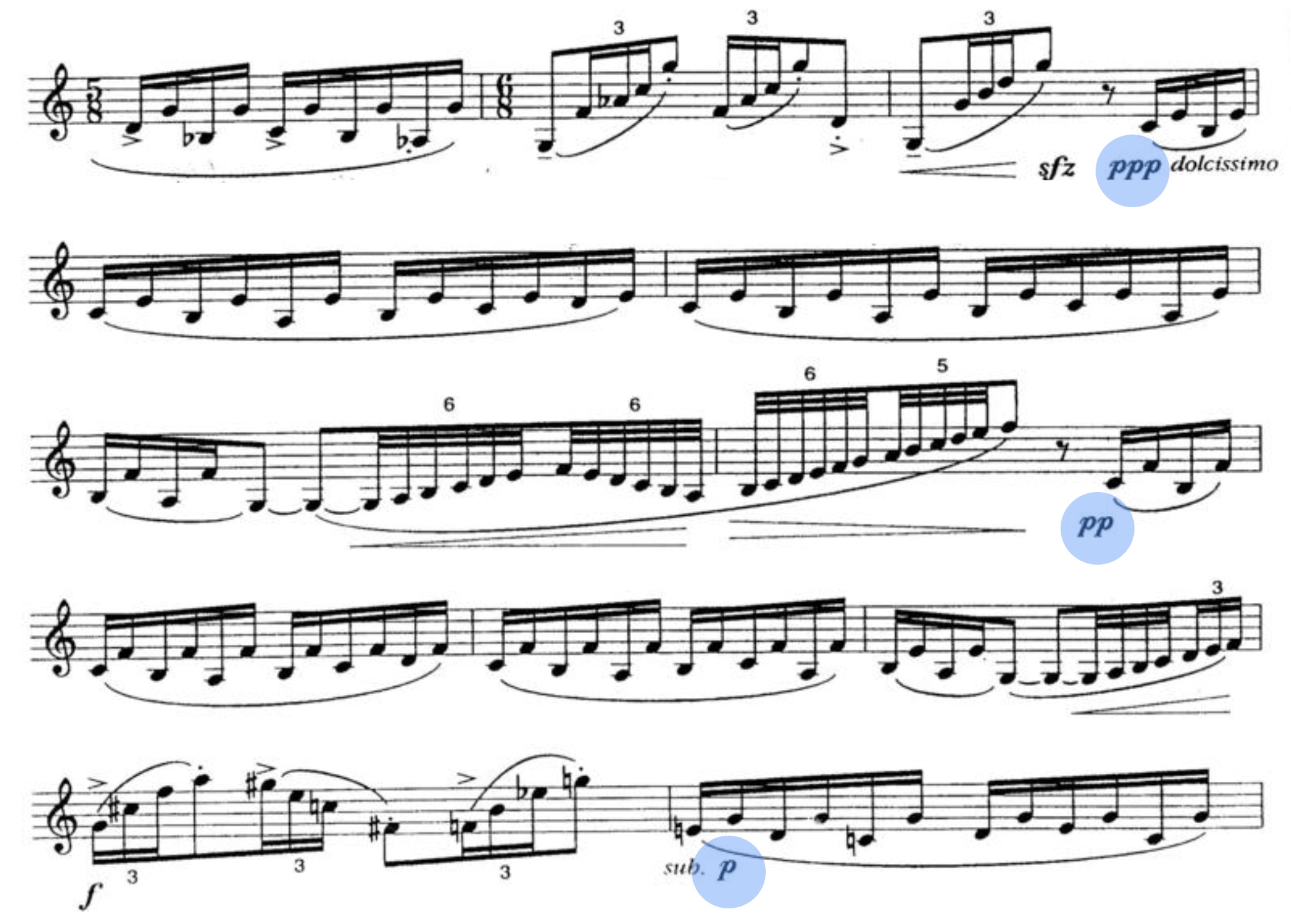

We now begin a new musical idea, more relaxed, dolcissimo according to Kovács’s score (see Fig. 7). I suggest a relatively calmer tempo, allowing for a more careful legato and giving space for the melodic line naturally to emerge. Kovács assigns different dynamics to each return to the melodic line; it is essential for the variations among ppp, pp, p and mf to be clearly distinguishable—a detail easily lost in larger halls or in more reverberant venues. In this section, I try for a less tense sound, providing slower and warmer air to the instrument.

Figure 7

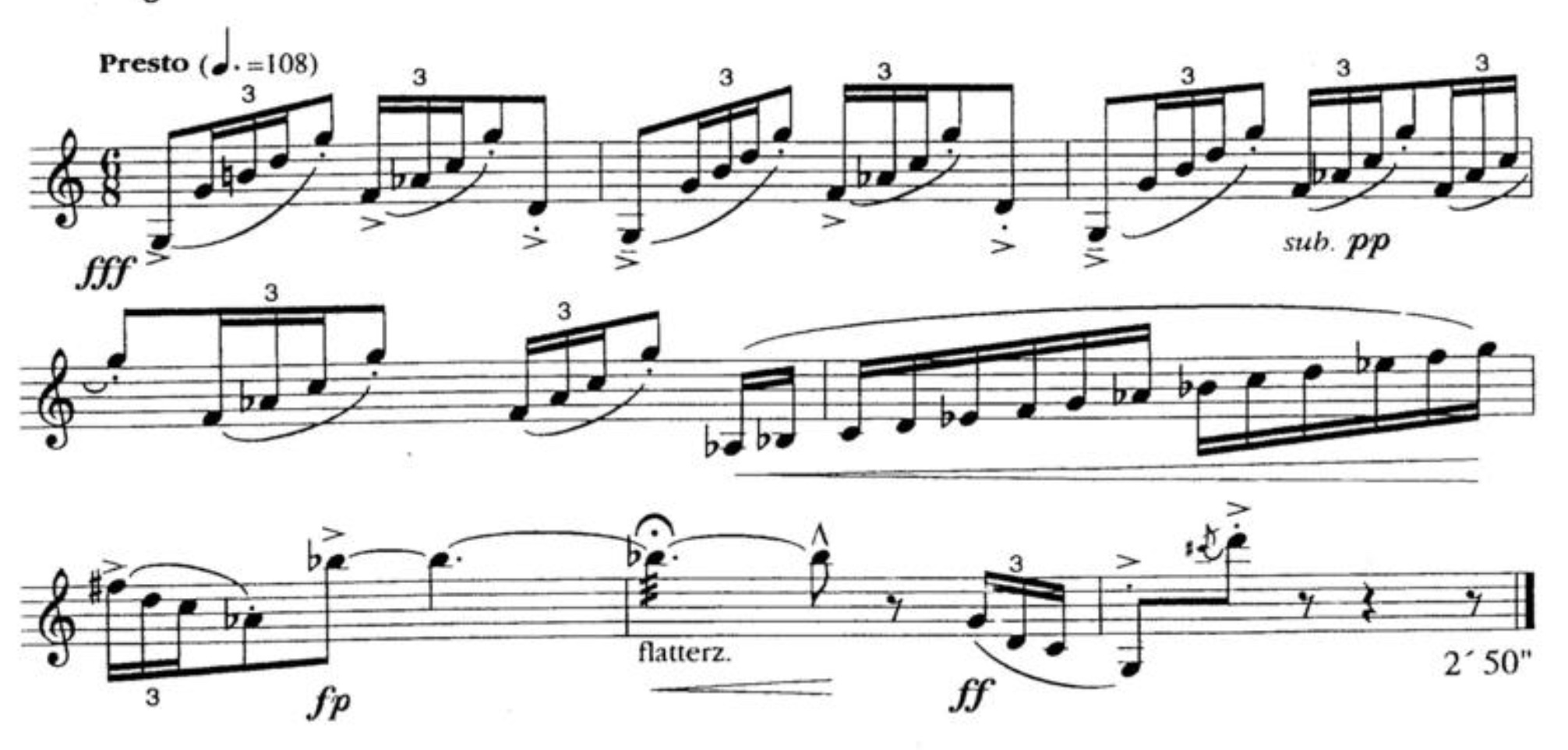

With the increase in dynamic intensity, we proceed towards a recapitulation of the initial material of the piece, this time charged with more “shock” and drama than at the beginning. This recapitulation serves as a bridge and a preparation for the final Presto. In contrast to the beginning, I suggest that the fermatas be shorter, leaving the phrases open and creating a greater feeling of agitation and anxiety upon reaching the virtuosic Presto.

Figure 8

Once again, in order for the Presto to have real musical impact, it is essential for the Moderato grazioso, where this theme is introduced for the first time, to be interpreted with calm and relaxation. This allows for the creation of an even more notable contrast. I like to see the Presto as a furious moment with maximum intensity (see Fig. 8). I recommend also that, after the last fermata (before the last triplet), there be a longer, almost theatrical rest, maintaining the body in tension, so as to give even more importance and emphasis to the final gesture.

The Hommage à Manuel de Falla is a work that requires not only a great technical command of the instrument, but also careful interpretive planning for how we want the audience to experience it, especially when it comes to the repetition of several musical motifs during the piece. Each detail—from accents, dynamics, and articulations to precise stylistic indicators such as grazioso or dolcissimo—is essential for one to interpret the work authentically. The true virtuosity of the work resides not in mere speed or technical show, but rather in a profound understanding of Kovács’s idea, which should lead to the music of Manuel de Falla, and ultimately to the roots of traditional Spanish music.

A version of this article in Portuguese is available at The Clarinet [Online]. Thank you to Paul Dixon for this English translation.

Vitor Fernandes is a Portuguese musician and one of the most sought-after clarinetists of his generation. A prizewinner at the Geneva and Ghent International Competitions, he performs worldwide as a soloist, recitalist, and orchestral musician. He has appeared with the Brussels Philharmonic, Sofia Philharmonic, and Kammerorchester Basel, and collaborates regularly with leading ensembles such as the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, Chamber Orchestra of Europe, and Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France. A committed educator, he has given master classes at institutions including HAMU Prague, Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing, Korea National University of Arts, and Hochschule für Musik Detmold.

Comments are closed.