Tips for Tuning

by Dr. Liz Aleksander

Associate Professor of Clarinet, University of Tennessee at Martin

As the saying goes, “It’s all relative.” This is particularly true when it comes to tuning. As much as we’d like tuning to be static, to just get the needle pointing straight up (or to find that smiley face on Tonal Energy), it isn’t that simple.

Tuning is affected by many factors, from dynamics to chords to the rest of the ensemble – even the weather! However, before you can adjust your intonation to account for these variables, you need to get your clarinet in tune in the first place. This means knowing where to make adjustments and how to adjust.

Where to Adjust

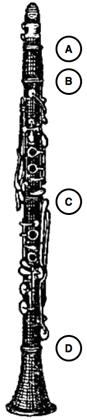

Tuning can be tricky on any instrument, and on the clarinet, it’s compounded by having five joints (and four connections). Before looking at how to tune, we need to know where (and where not!) to adjust.

- Mouthpiece-barrel. This should always be pushed in all the way so that the mouthpiece is stable. Never adjust at this juncture.

- Barrel-upper joint. Adjustments here affect the entire instrument, so always tune here first. If the throat tones and left-hand notes (chalumeau D to Bb and clarion A to C) are out of tune, then adjust here. If those notes are in tune, then adjustments need to be made farther down the clarinet so that these notes stay in tune.

- Upper joint-lower joint. This intersection only affects intonation for part of the instrument (chalumeau E to C# and clarion B to G#). If the throat tones and left-hand notes are in tune but lower notes are out of tune, this is where adjustments should be made.

- Lower joint-bell. This connection only affects low E and clarion B (notes with all fingers down and all side keys closed). Typically, you won’t need to adjust here unless those notes are always out of tune; then, you’ll always need to pull out the same amount at this connection, and you should get in the habit of doing so when you assemble your instrument.

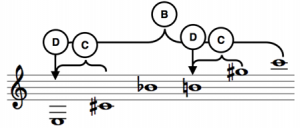

The following diagram shows which notes are affected by adjustments at B, C, and D:

How to Adjust

If you hear that you’re out of tune but don’t know if you’re sharp or flat, you can alter the amount (not speed) of your air to figure out how you need to adjust your instrument.

- Use more air. (Using more air lowers the pitch.) If tuning improves, you’re sharp, so you need to pull out at the appropriate connection.

- Use less air. (Using less air raises the pitch.) If tuning improves, you’re flat, so you need to push in at the appropriate connection.

In the end, remember that you need to tune how you play. You can certainly use this method to figure out whether you need to pull out or push in, but you do need to adjust the length of your instrument. If you don’t (if you settle for getting your instrument in tune by playing with more or less air than you normally use), then you’ll need to use that same amount of air in order to stay in tune — or you’ll play out of tune, which is the more common result.

Suggested Tuning Method

That’s a lot of information, but it can be boiled down into a simple tuning procedure. The goal here is to get the instrument to a place where most notes are in tune and those that aren’t can be adjusted while playing, using the air, embouchure, alternate fingerings, etc.

After you’ve warmed up:*

- First, tune chalumeau F# (if tuning to concert A) or open G (if tuning to concert Bb). Use more air or less air if you aren’t sure whether to pull out or push in. Adjust between the barrel and upper joint; repeat until this note is in tune.

- Then, tune the clarion B (for concert A) or C (for concert Bb). Again, use more or less air to figure out is you need to pull out or push in. Adjust between the upper and lower joints and repeat until this note is in tune.

*Remember that if your low E and clarion B are consistently sharp to the rest of your instrument, you should pull out at the bell when you assemble your instrument, before you do this.

Improving Your Intonation

Once you’ve gotten comfortable with tuning your instrument, you can work to improve your intonation using some of the following strategies:

- Complete an intonation chart to determine your instrument’s intonation tendencies. First, warm up as usual and tune your instrument. Then, play each note and write down how sharp or flat it is (in cents) using a chart like this one: http://www.woodwind.org/clarinet/Misc/Tuning/clarchrt100.gif

When I do this, I like to jump around the instrument (instead of playing a chromatic scale) so that I don’t use my ear to adjust the size of the half-step in relation to the previous note. I also like to do this on three separate days and then average the tendency for each note.

- Experiment with alternate fingerings (in the altissimo) and coverings (on throat tones). You’ll find that these help tone as well as pitch.

- Play your long tones against a drone pitch. Begin with octaves, fifths, and chords; as your ear improves, work to play more challenging intervals against the drone.

- Play long tones while holding down the piano’s damper pedal (on the right). This works well with octaves, fifths, chords, 12ths, and extended 12ths.

While you play the last two exercises, you should listen for a difference tone, which is the “extra” note you hear when playing in tune. Sometimes when people hear a difference tone, they try to adjust their tuning to get rid of it, but difference tones are good! They only happen when two (or more) notes are in tune, and they get stronger as the notes become more in tune. So, it’s important to get comfortable with difference tones in your individual practicing and to listen for them in ensembles.

Thanks to Karen Hatzigeorgiou for the public-domain image of the clarinet, available on her website: http://karenswhimsy.com/woodwinds.shtm

Comments are closed.